A media scandal in Ukraine is making waves outside the country after a website exposing identities of Russian-backed militants in eastern Ukraine published hacked personal information on all journalists ever having received accreditation in the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People's Republic" (“DNR”), which is considered a terrorist organization in Ukraine, along with its counterpart, the “Luhansk People’s Republic.” Ukrainian and foreign journalists have called upon Ukrainian security services to investigate the situation and punish those who published the journalists' data online. Why was this data published in the first place and what are the implications? Euromaidan Press investigated.

1. What happened?

A site called Myrotvorets published a list of journalists who had been given official accreditation in the self-proclaimed Russian-backed statelets in eastern Ukraine starting from 2014. The data was obtained from a leak of data from “DNR” officials. The list, published online under the provocative filename “scoundrels,” includes names of 4508 journalists, fixers, translators, cameramen, photographers, and other media professionals, as well as workers of other organizations, their mobile numbers, and emails. On the site, Myrotvorets commented that the publication of the list “is needed because these journalists collaborate with the militants of a terrorist organization.”

When asked to clarify what is meant by “collaborating,” Roman Zaitsev, head of Myrotvorets, said in a comment to Euromaidan Press that this entails “entering certain mutual relations and giving bilateral commitments.” “The word ‘collaboration’ means that subjects enter into some sort of relationship. But some Ukrainian journalists with a bad knowledge of Russian language probably interpreted it as ‘abetting,’ which means helping. It would be good that they learned the Russian language; there is a war going on, and one needs to know the language of the enemy,” Mr. Zaitsev concluded.

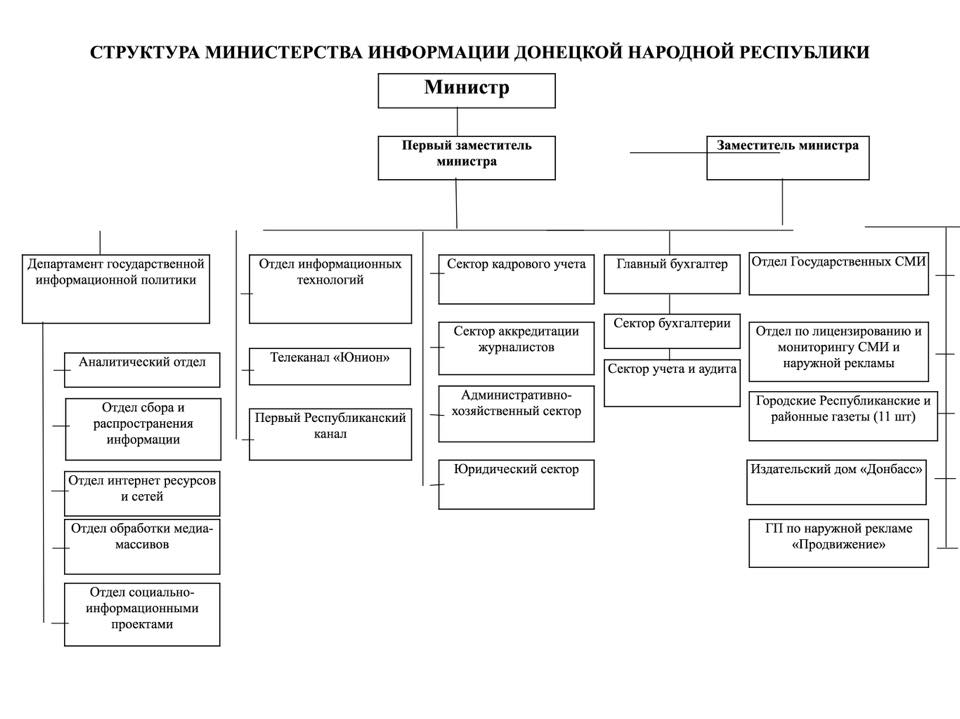

The list was advertised by Anton Herashchenko, a Ukrainian MP and advisor to Ukrainian Minister on facebook, who stated that Ukraine needs to establish a “program of information policy” which would include “control over accreditation of journalists of foreign and primarily Russian media on the territory of Ukraine and expulsion of those journalists if it is established they violate Ukrainian law.” Violation of Ukrainian law in this case mostly entails crossing into the occupied territories from Russia’s side. Apart from the database of journalists, this leak from the “DNR” allowed reconstructing the structure of its “propaganda apparatus,” the budget of which Herashchenko claims exceeds the budget of Ukraine’s Ministry of Information at least tenfold.

Myrotvorets has also promised to follow up with a publication revealing journalists who have received awards from “DNR” authorities.

The prosecutor’s office of Kyiv has opened criminal proceedings against the list's publishers, following journalists’ complaints of incoming threats.

2. Who is on the list?

The list is incredibly diverse and includes a wide variety of media representatives from different countries and outlets. Among them are western journalists known for their widely-acclaimed coverage of the conflict in Donbas. Simon Ostrovsky, the author of an award-winning investigation tracking Russian soldiers fighting in Ukraine called “Selfie Soldiers: Russia Checks in to Ukraine,” is one of them. In 2014, Ostrovsky was kidnapped and spend three days in the militant’s prisons. Journalists of BBC, AlJazeera, Reuters, CNN, Deutsche Welle and other outlets are also in the list. But at least as many are journalists of press services of the self-proclaimed “republics,” correspondents of the Russian-backed militant brigades such as “Oplot” and “Russian orthodox army” (the latter proclaims it is waging a holy war in Donbas), as well as Russian-government funded outlets known for their falsified and skewed reports about Ukraine (LifeNews, RT, and others. Selected Ukrainian media are also present.

3. What is Myrotvorets?

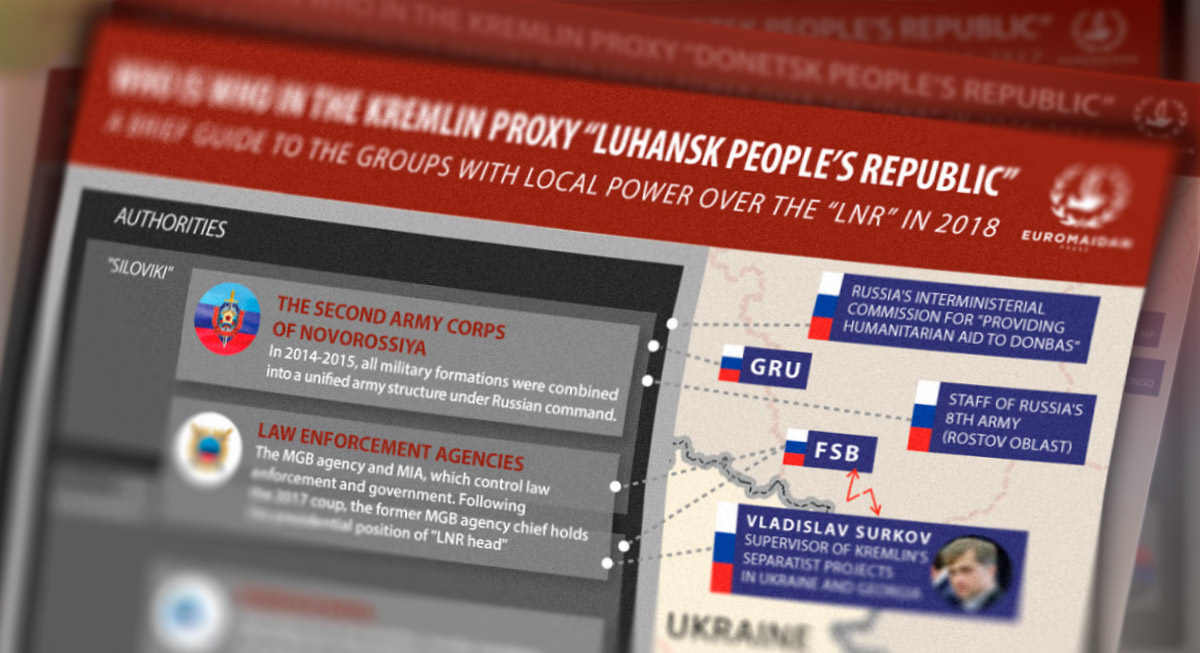

Myrotvorets describes itself as an NGO that researches crimes against the national safety of Ukraine, peace, safety of mankind and international law. Created in 2014, its primary activities include collecting open-source information on identities of militants who fight against the Ukrainian army in Donbas, joining the ranks of the “armies” or battalions of the so-called “republics,” as well as testimonies of people leaking information known to them. The site collaborates with Ukraine’s Security Service (SBU), General Staff, Ministry of Interior, Penitentiary Serviсe, and Border Guard, and is headed by SBU representative Roman Zaitsev. One of their special operations involved getting hold of documents showing a plan of a major Russian invasion in 2015.

4. Why this attack on journalists?

To place the incident into context, it is important to recall that Ukraine is a victim of Russian hybrid war, a major part of which is an information war. Russia’s Minister of Defense once called media “another arm of the armed forces.” The mechanism with which Russian misinformation ignites war is all too familiar for people living in Ukraine, but episodes like made-up reports of a girl that was never killed in Donbas, covered by the BBC, or RFE/RL’s interview of a Kyrgyz retired servicemen who came to fight as a mercenary in Donbas under influence of Russian propaganda got circulated among foreign audiences. Episodes when Russian journalists manipulate and falsify interviews to promote the Kremlin’s narrative, igniting international hatred and fueling the Russian-backed conflict in Donbas, are all too well documented by the website russialies.com. Many of those journalists are in the list.

That being said, there are plenty of Russian and foreign journalists working for independent media outlets giving fair coverage of the conflict, who also received accreditation from the self-proclaimed “republics” and are insulted by being placed in the same category.

Another concern is that of Ukrainian journalists visiting the occupied territories who promote the Kremlin’s view of a “civil war” in Ukraine, which is in many occasions enabled by local residents repeating what they saw from Russian or separatist channels on their television screen (like in the situation with the BBC report on the girl that was never killed). The population of Donbas is being told each day that it is the Ukrainian army that is responsible for the war and not the Russian-backed and led insurgency. An element of Russia’s hybrid war against Ukraine is getting the Ukrainian population to believe this narrative in order to discourage Ukrainian army efforts, as well as pushing a scenario that will be favorable for Russia - maintaining a frozen conflict in Ukraine that will allow Russia to control Ukraine’s political situation, with Ukraine paying for the party. Common narratives for this are “Ukraine is attacking its own population,” “Donbas people should be heard,” “Ukraine should maintain social payments to the self-proclaimed territories that are waging war against it.”

While Ukraine, due to political reasons, has not declared itself to be officially at war with Russia, it is nonetheless being attacked for the second year in a row by a hybrid army involving active Russian army servicemen and weapons, taking away Ukrainian lives, and by Russian media which is operating by the laws of war. Reconciling needs of information security and requirements of free press which is an essential for a democratic state at times of peace is so far an unresolved challenge for Ukraine.

5. Does publishing this data endanger the journalists?

Most of the information found in the database can be found through other means. Journalists often provide their emails in the profiles of their outlets or social media accounts. However, Muzaffar Suleymanov, a representative of the Committee to Protect Journalists, stated in an interview to Voice of America that many might be operating under pseudonyms for the sake of security, and that publishing this list puts their life under danger because they have started to receive threats via phone and email. Other journalists have expressed fears that they will have trouble with getting accreditation to cover events in Ukraine.

Among Ukrainian audiences, this statement raised a question of why the journalists felt safe when providing their personal data to a terrorist organization which is widely known for its torture, kidnappings, and human rights violations, but are uneasy when this data is made public among Ukrainians. One response to that might be that the publication of such a list invites Ukrainian adventure-seekers (presumably, nationalists) to use it to bother the journalists in an organized manner.

Ostensibly, the main legal implications for journalists will be, in cases when they entered the separatist “republics” from Russia and thus violated Ukrainian law, a denial of accreditation in Ukraine. This is envisioned to apply to many Russian journalists working for propaganda outlets.

In a noteworthy parallel, a list of foreign journalists given accreditation in Russia is officially published on the website of the MFA. It contains, apart from telephones and emails, addresses of where the journalists are staying in Russia. However, this list differs from the Myrotvorets one in that none of the journalists were labeled as collaborators with terrorists in it, and it is highly likely that they gave permission for their data to be published.

6. What were the reactions?

The publication has sparked extreme controversy in Ukrainian society.

Myrotvorets opponents

An open letter signed by Ukrainian and foreign journalists demands to remove the database from the site, stressing that accreditation doesn't mean journalists are colluding with any of the sides of the conflict, but is a form of protection and security for the journalist, and claims that journalists started receiving threats via phone and email, and that the publication violates the Constitution of Ukraine, the European convention of human rights, and law of Ukraine “On Protection of Personal Data” (read the full translation on Global Voices). The OSCE has responded by expressing concern about journalists’ safety:

.@OSCE_RFoM Mijatovic expresses concern about journalists’ safety in #Ukraine https://t.co/pN7y5GRNt3 #journosafe pic.twitter.com/NdC3SVk5eX

— OSCE media freedom (@OSCE_RFoM) May 11, 2016

The Committee to protect journalists has condemned the publication and denounced Heraschenko for his praise of the action. The EU Delegation to Ukraine has also called upon Ukrainian authorities to remove the publication.

Opponents of Myrotvorets’ publication note that it is in Ukraine’s interests to have international coverage of the conflict from both sides, as journalists help raise awareness about the war in Ukraine in the world, as well as expose Russia’s involvement in the war. Well-known examples include the interview of Elena Kostiuchenko, whose interview with an injured Buryat tankman exposed the role of Russian contract soldiers taking part in the war in Ukraine and Simon Ostrovsky’s Selfie Soldiers, who reconstructed the path of a Russian soldier coming to fight in Ukraine by the georeferenced photos he posted in social media. Russian journalist Timur Olevsky commented to Meduza that “accreditation is necessary in the ‘DNR’ in order to work without being persecuted,” adding that he would receive accreditation in ISIS if it were necessary.

Evgeny Feldman, journalist of the Russian independent outlet Novaya Gazeta, said in a comment to Global Voices that "a journalist’s task is to find a possibility to work honestly, navigating between these necessary and unavoidable restrictions. I like to think I was able to do that, capturing both the key points of the war itself and the difficult lives of the civilians." He claims that his main professional point of pride is being able to help several Ukrainians in the occupied territories - namely, several Ukrainian soldiers who were captured, made to march in the “parade” in Donetsk and forced to do labor in Ilovaisk. "This is probably my main professional point of pride during the five plus years I’ve been in the profession," he adds.

Mr.Suleymanov from the Committee to Protect Journalists stressed that it is unfair to label all 4000+ journalists as terrorists, while they were only performing the necessary actions to be able to do their work, that receiving accreditation from any authority does not mean condoning it, and that journalists collaborate with their editorial offices and not authorities of any official structures.

Philosopher and Hromadske journalist Volodymyr Yermolenko commented that the Herashchenko-Myrotvorets publication is "perhaps, one of the largest recent blows to Ukraine's reputation in the world," noting that the "truth that they [foreign journalists] told was the main instrument to counter Russian propaganda in the West. [...] To consider them as people who 'collaborate' with the enemy is simply naive. And incompetent. Publishing their personal information is a crime."

Myrotvorets defenders

Meanwhile, voices sounding in defense of Myrotvorets’ publication raise first of all the issue of ethics of receiving accreditation from structures of an organization designated as terrorist in Ukraine, which essentially legitimizes the structure. Political commentator Portnikov claimed that it is hard to imagine an Israeli journalist being accredited at a “ministry of information” of Hamas, and a Georgian journalist receiving accreditation at the “authorities” of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and thus Ukrainian (not foreign) journalists receiving accreditation from “DNR” is “hypocrisy” and “violation of professional and national honor” that immerses their audience in an “ocean of lies.”

Myrotvorets head Roman Zaitsev came out with a publication featuring fragments of correspondence between employees of “DNR’s” information ministry, in which it is noted that out of 4769 journalists, 69 were denied accreditation because of “incorrect and unobjective” coverage of the situation in the self-proclaimed statelet, suggesting that accreditation means journalists cover the situation in a way that is condoned by “DNR” authorities. However, this claim is hardly consistent with the list of journalists, among which are foreign journalists who worked on covering the MH17 crash.

First deputy chairman of the Verkhovna Rada Iryna Herashchenko noted that supposed protection granted by accreditation in the occupied territories was illusory in the case of humanitarian missions, which started registering with the self-proclaimed authorities of the “republics,” defying Ukrainian law and international norms, which specify that accreditation granted by a state applies for all of its territory, and legitimizing the militants by complying with their demands and giving into blackmail. Herashchenko specified that despite this, humanitarian missions are being barred from the occupied territories by the militant’s arbitrary actions: starting from 2005, “Medics without borders” and UN structures were expulsed from the “LNR” and “DNR,” and other missions are being prohibited from carrying out activities.

Dmytro Tymchuk, a military journalist and coordinator of the group “Information resistance,” stressed that starting from 2014 when Ukraine’s Prosecutor General designated the “LNR” and “DNR” as terrorist organizations, maintaining any official relations with them is collaboration, and no other interpretations are possible. He noted that it’s hard to imagine that a CNN group that received accreditation from the Taliban would film artillery attacks on US army positions. In this regard, it is worth recalling that former Deutsch Welle reporter Kitty Logan lost her Ukrainian accreditation after she encouraged separatists to fire on Ukrainian positions for an effective story.

Furthermore, Tymchuk suggests that Mr. Tombinski, Head of EU delegation to Ukraine, names some EU journalists who received accreditation in ISIS or Al-Qaeda. He claims that Ukrainian prosecutors would be better off investigating acts of collaboration with terrorists, and notes the hypocrisy of a situation when the Prosecutor’s office failed to react when militants of the “Russian liberation front” vowed to hunt down and kill a number of Ukrainian journalists for spreading what they called "western lies." “At the end of the day, I can understand only one instance of receiving accreditation in the ‘LDNR’ - when it is done by representatives of Russian propaganda media. All other incidents are outside the realm of Ukrainian law, ethical norms, and morality.”