Political emigres have long played a much greater role in Russia and especially in Russian thinking than in other countries, the result among other things of the fact that Lenin and a tiny band of emigres returned from abroad in 1917 and in the space of a few months carried out a revolution.

Now, as a result of Vladimir Putin’s increasing repression at home, ever more Russians are choosing to leave the country not simply for better economic opportunities as was true during the first post-Soviet years but for political reasons. And they are increasingly the focus of Moscow’s concerns and attacks.

In today’s “Nezavisimaya gazeta,” Aleksey Gorbachev, that Moscow paper’s political observer, discusses this unfortunate if not unexpected development and points out that “opposition figures who go abroad are now being accused of organizing color revolutions” and even being charged in absentia in Russian courts.

Last Friday, without either the accused or his lawyer being present, Pavel Shekhtman, who has emigrated to Ukraine, was “arrested” in absentia by a Moscow court. Also last week, Finland gave political asylum to Andrey Romanov, formerly of Magnitogorsk. Both were accused of extremism because of their pro-Ukrainian posts on social networks.

Olga Kurnosova, a leader of the Russian political refugees in Kyiv – and there are now enough of them that one can speak of such a position, told “Nezavisimaya gazeta” that Moscow is seeking to “accuse many of those who have left Russia of making plans for a color revolution” in their homeland.

Shekhtman, who had been under house arrest in Russia, fled to Ukraine where he sought political asylum because he was threatened with up to five years in Russian prison camps for web posts asserting that Russian soldiers have been “killing Ukrainian prisoners who refuse to make declarations on Russian channels.”

He says that he “will return to Russia only if the [Putin] regime falls.”

Romanov faced similar charges and an order for his arrest was issued last December, but before it could be acted upon. The Magnitogorsk internet activist fled together with his family to Finland. On Friday, a Finnish immigration court informed him that he had been granted political asylum in that country, a status which means he won’t be handed over to Russian officials.

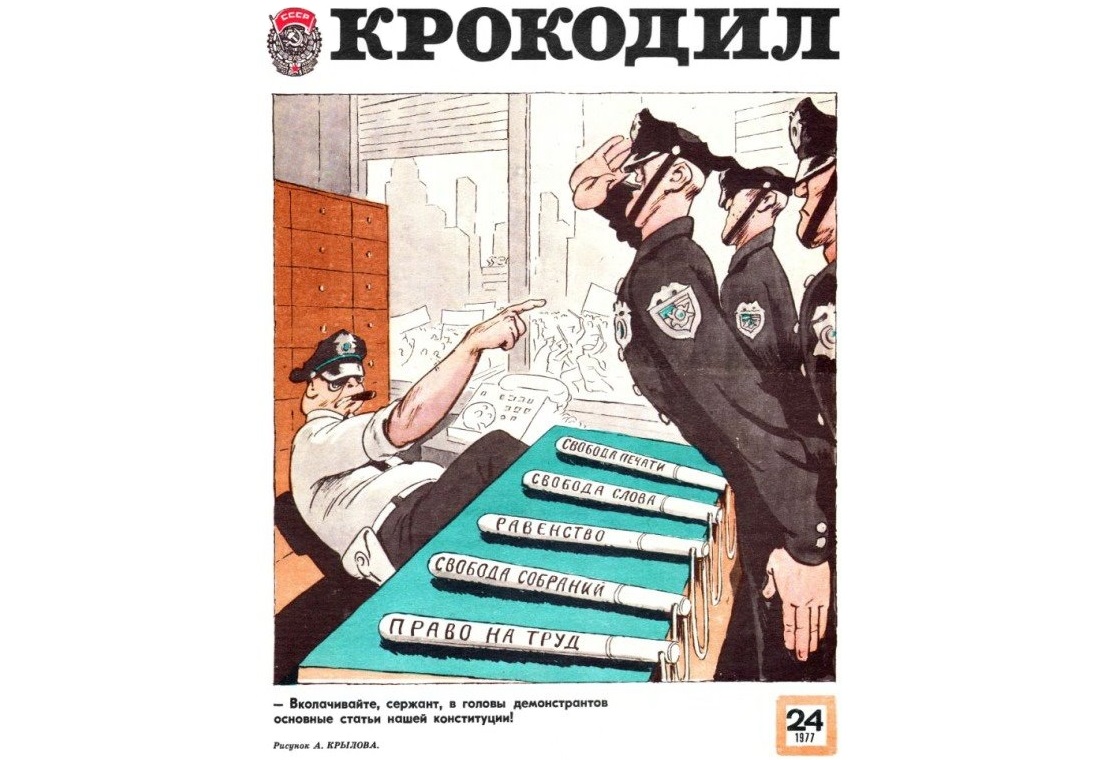

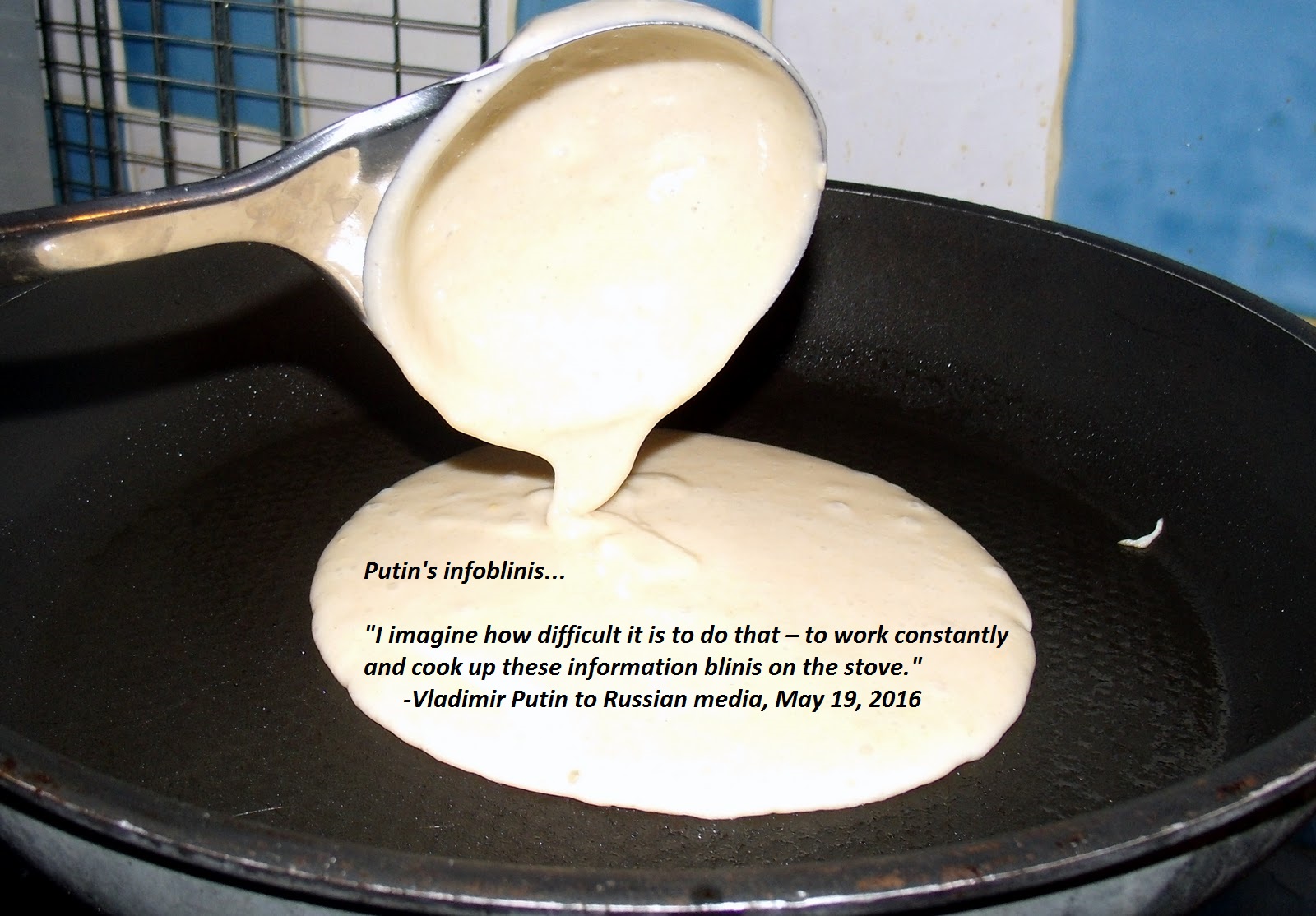

The increasing number of such political emigres, the “Nezavisimaya gazeta” writer says, has not passed unnoticed by the Russian authorities. Moscow has deployed not only diplomatic and law-like means but also launched media campaigns in the countries to which they have fled, accusing them of fomenting a revolution at home and threatening bilateral ties.

This campaign is clearly “coordinated,” Kurnosova says from Kyiv. And she notes that when she and others in her status try to speak via internet telephone with their friends in Russia, the connections are jammed with the same kind of “music” that the KGB used against Western radio stations in Soviet times.

Konstantin Kalachev, head of the Moscow Political Expert Group, told the newspaper that in his view, suggestions that those who have emigrated are plotting a color revolution is “the only argument which the authorities can advance to justify the fact that people who think differently have been forced to leave the country.”

“If people who think differently did not exist, they would have to be invented to justify the fact that they are being forced to leave the country. The theme of a color revolution in Russia today sounds like unreal science fiction. But the siloviki prefer to protect themselves” by pushing people out and thus justifying what the organs are doing.