After the Crimea was annexed and after the war in the Donbas was unleashed a lot has been said about the Kremlin’s so-called “hybrid war.” A war that, according to the theoreticians, combines elements of “regular” military action with reconnaissance and subversive operations carried out by subdivisions; an all-out information and cyber war is waged as well. Those same theoreticians and analysts claim that this is a completely new form of warfare.

There is nothing new in “hybrid warfare.” The strategy, in one measure or another, in one combination of elements or another, was practiced long before Putin’s “little green men” appeared in Crimea or in the Donbas. Inasmuch as back then this kind of terminology did not exist, in secret documents this kind of strategy was referred to as “active reconnaissance” while openly it was called partisan activity, or an insurgency, or, later, it was labeled a people’s liberation war or a revolution of national independence.

“Our finger of revolution has been stuck into China”

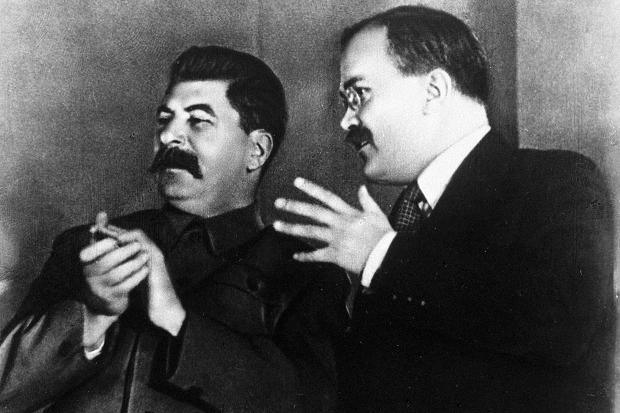

On October 7, 1929 Stalin, who had come to Sochi for his well-deserved multi-month vacation, sent a message with many questions to his stand-in in Moscow, Molotov (at the moment Molotov was a member of the Politburo, and the Secretary of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolshevik)):

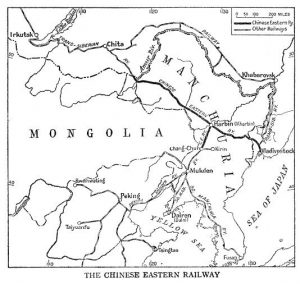

A bit of background history. The Chinese Eastern Railway (CER) was a bone of contention between Russia and China at that time. The story of the conflict surrounding the railway differs radically depending on the source: Soviet historians and contemporary historians who study Russian fiscal proceedings maintained and still maintain today that the Chinese military were to blame for rushing to take over the administration of the CER from the deserving USSR. Meanwhile, the Chinese contend that it was precisely the USSR that introduced conflict into the situation by consistently breaking the terms of the agreement that had been reached in 1924 about joint administration. What’s more, the railway was unprofitable; it was a deeply debt-ridden enterprise. For the actual ruler of Manchuria, Chairman Zhang Zuolin, the CER was a strategic conduit, and he was not about to pay for the use of the rail to transfer troops, nor could he. The Chinese military threatened to impose executions on members of the Soviet administration for its efforts to block the transfer of echelons of armed soldiers without tickets. After that Zhang Zuolin devoted all his efforts to methodically take over the conduit. It became painfully obvious that they could not sustain the route, the route would never be profitable under Soviet administration, plus in enemy territory its strategic importance would, for all purposes, be zero. Back in 1926 in Moscow a few clear-headed “party comrades” expressed an opinion that “we ought to straighten out the situation with the CER as quickly as possible, get rid of it like a callous on our foot.” (Stalin’s Letters to Molotov…p.77.) However, as was loudly proclaimed at the July (1926) plenum of the Central Committee, the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the All Union Communist Party (Bolshevik) by an ardent member of the Politburo, Nikolai Bukharin, “we have a problem with the CER, with the rail line, which is a principal strategic line and is our finger of revolution that has been stuck into China.” [Ibid.]

A bit of background history. The Chinese Eastern Railway (CER) was a bone of contention between Russia and China at that time. The story of the conflict surrounding the railway differs radically depending on the source: Soviet historians and contemporary historians who study Russian fiscal proceedings maintained and still maintain today that the Chinese military were to blame for rushing to take over the administration of the CER from the deserving USSR. Meanwhile, the Chinese contend that it was precisely the USSR that introduced conflict into the situation by consistently breaking the terms of the agreement that had been reached in 1924 about joint administration. What’s more, the railway was unprofitable; it was a deeply debt-ridden enterprise. For the actual ruler of Manchuria, Chairman Zhang Zuolin, the CER was a strategic conduit, and he was not about to pay for the use of the rail to transfer troops, nor could he. The Chinese military threatened to impose executions on members of the Soviet administration for its efforts to block the transfer of echelons of armed soldiers without tickets. After that Zhang Zuolin devoted all his efforts to methodically take over the conduit. It became painfully obvious that they could not sustain the route, the route would never be profitable under Soviet administration, plus in enemy territory its strategic importance would, for all purposes, be zero. Back in 1926 in Moscow a few clear-headed “party comrades” expressed an opinion that “we ought to straighten out the situation with the CER as quickly as possible, get rid of it like a callous on our foot.” (Stalin’s Letters to Molotov…p.77.) However, as was loudly proclaimed at the July (1926) plenum of the Central Committee, the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the All Union Communist Party (Bolshevik) by an ardent member of the Politburo, Nikolai Bukharin, “we have a problem with the CER, with the rail line, which is a principal strategic line and is our finger of revolution that has been stuck into China.” [Ibid.]

Insofar as the Soviets had absolutely no desire to pull out their “revolutionary finger" out of China, Moscow tried to solve the problem Stalin-style: getting rid of the problem by getting rid of the person. On June 4, 1928 the train car in which Zhang Zuolin was traveling exploded near Mukden. A mine had been set up in a viaduct. Shortly thereafter the gravely wounded Chairman died in a Mukden hospital. Even though the Japanese were immediately blamed for the assassination attempt, today it is known that the assassination was executed by a resident INO OGPU agent [foreign division of the Soveit secret service] in Harbin, Naum Eitington and a resident agent at the foreign division administration (reconnaissance department) RCCA headquarters, Christopher Salnin. That did not solve the problem, though, because Zhang Zuolin, the son of the assassinated Zhang Tzolin refused to listen to the “convincing” arguments of the Kremlin. This was an example of organized “rebel acts” in action, introduced by Stalin. In the end, of course, it was decided to make use of direct force: at the boundary artillery forces, the cavalry, and the infantry were deployed. On 12 October, 1929 groups of special forces created by the Special Far East Army specifically for that campaign attacked and conquered the city of Lakhasusu (Tuntsian) in Khuiluntzian province and demolished half the fleet of the Chinese Sunhari flotilla. On 30 October, 1929, the ships of the Soviet Far East Navy flotilla deployed troops at the Sunhari estuary, finished off the rest of the Sunhari flotilla while two Soviet land regiments conquered the city of Futzin. A simultaneous incursion across the Soviet-Chinese border was carried out by Soviet troops into Prymorie, not far from the city Mishanfu. They massacred the Chinese soldiers, concluded a new agreement regarding the CER and formally established a joint administration. Soon the “revolutionary finger" had to come out of China though, because the Japanese conquered and subsequently occupied Manchuria.

Insofar as the Soviets had absolutely no desire to pull out their “revolutionary finger" out of China, Moscow tried to solve the problem Stalin-style: getting rid of the problem by getting rid of the person. On June 4, 1928 the train car in which Zhang Zuolin was traveling exploded near Mukden. A mine had been set up in a viaduct. Shortly thereafter the gravely wounded Chairman died in a Mukden hospital. Even though the Japanese were immediately blamed for the assassination attempt, today it is known that the assassination was executed by a resident INO OGPU agent [foreign division of the Soveit secret service] in Harbin, Naum Eitington and a resident agent at the foreign division administration (reconnaissance department) RCCA headquarters, Christopher Salnin. That did not solve the problem, though, because Zhang Zuolin, the son of the assassinated Zhang Tzolin refused to listen to the “convincing” arguments of the Kremlin. This was an example of organized “rebel acts” in action, introduced by Stalin. In the end, of course, it was decided to make use of direct force: at the boundary artillery forces, the cavalry, and the infantry were deployed. On 12 October, 1929 groups of special forces created by the Special Far East Army specifically for that campaign attacked and conquered the city of Lakhasusu (Tuntsian) in Khuiluntzian province and demolished half the fleet of the Chinese Sunhari flotilla. On 30 October, 1929, the ships of the Soviet Far East Navy flotilla deployed troops at the Sunhari estuary, finished off the rest of the Sunhari flotilla while two Soviet land regiments conquered the city of Futzin. A simultaneous incursion across the Soviet-Chinese border was carried out by Soviet troops into Prymorie, not far from the city Mishanfu. They massacred the Chinese soldiers, concluded a new agreement regarding the CER and formally established a joint administration. Soon the “revolutionary finger" had to come out of China though, because the Japanese conquered and subsequently occupied Manchuria.

“Lots of noise but no explosion”

At first the fervor those red subversives operating in the Far East possessed lived on despite the failed operation; that is, until they were caught in the act. On 7 July, 1932 the Consul at the Japanese Embassy in Moscow handed the NARKOMAT [Pepole’s Commissariat] of foreign affairs of the USSR a note from the Japanese government in which the following was said: a Korean named Lee who was arrested by Japanese authorities gave testimony that together with three other Koreans he had been recruited by the OGPU [Soviet secret service], supplied with explosives and dropped into Manchuria with a mission to detonate a series of bridges. According to the self-criticizing information given in Moscow by Terenti Derybas, supervisor of the official delegation of the OGPU responsible for the Far East, the operation he had organized had failed: “we made lots of noise but the bridge did not explode.” (Lubianka. Stalin and the VChC-GPU-OGPU-NKVD. Stalin Archives. Documents of senior party and government organs. January 1922-December 1936. M., International Fund “Democracy,” 2003, p. 807.) Moreover, the agents who were supposed to detonate the bridge were caught, and they admitted to everything.

Stalin, who was again vacationing in the south and already had information about the scandalous fiasco of the Chekists [agents of the “old” secret police] even before he received the official Japanese “advertisement,” wrote to his stand-in in Moscow, member of the Politburo and Secretary of the Central Committee, Kaganovich:

“The criminal violation of a directive authorized by the Central Committee is not to be disregarded without giving it due attention as regards the inadmissibility of acts of sabotage perpetrated by the OGPU and Razvedupr [Reconnaissance Management] in Manchuria. The arrest of Korean explosives experts and the participation of our agents in that operation creates (can create) a new danger in that provocations will be put to use in the conflict with Japan. Who needs that, if not the enemies of the Soviet authorities? It is essential to summon the supervisors of the Far East department to explain the situation and punish according to standard procedure those who have violated the interests of the USSR. No more enduring such abomination! Talk with Molotov and apply draconian measures against those criminals in the OGPU and the Razvedupra (there is great likelihood that those men are enemy agents among us). Demonstrate that in Moscow there is still rule of law and criminals are punished severely. Greetings! J. Stalin” (Stalin and Kaganovich. Correspondence. 1931-1936. M., ROSSPEN, 2001, p.208.)

On 2 July, 1932, Kaganovich informed his chief that he had cleared up the situation with the Korean subversives and that Stalin had been proven right: “regretfully, it was the OGPU (the old holdovers). In case Hirota (he has instructions) has any questions we have instructed Karakhan how to handle the questions.” (Ibid., p.212) (Hirota Koki served as ambassador to the USSR 1928-32; Lev Karakhan was deputy people’s commissar in foreign affairs).

At the same time Kaganovich informed Stalin that “days ago some kind of representative of the Chinese People’s Army appeared at our boundary post with a letter for Bliukher (Vasili Bliukher was commander of Special Red Flag Far East Forces –Ed.) regarding weapons, etc. We gave instructions to immediately send him back and forbid access to our boundary post for similar representatives, no matter if they are undercover provocateurs or are innocently performing the role of provocaterus.” (Ibid.)

Consider the following: this means that similar advances into “the war market” were completely routine and common for Bliukher. Except that after the failed mission it was necessary to take a strategic pause, to discontinue the “war market” for review and assessment. On 16 July, 1932 the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolshevik) reviewed the “DVK Problem” and resolved to “focus the attention of the OGPU on the fact that the planning of the mission was unsatisfactory; the people who were selected for the mission had not been properly checked” therefore “make it plain to comrade Derybas that he had failed at according the extremely important mission the required attention especially in the selection and thorough examination of the personnel.” An order was issued that “the party responsible for the poor organization of the mission,” chief of the Vladivostok GPU Operations Section, Nikolai Zagvozdin must be promptly and severely reprimanded and “to recall comrade Zagvozdin from Vladivostok.” The GPU was ordered “to strengthen the cadres of the war operations sector.” (Lubianka…, p.315.)

Of course any participation of Soviet security forces in terrorist acts was to be denied. The Deputy People’s Commissar of foreign affairs Lev Karakhan summoned the Japanese ambassador and told him that “all the testimony provided by the Korean, Lee, has turned out to be, from beginning to end, an angry and provocative fabrication. Neither the Vladivostok GPU nor any other Soviet institution in Vladivostok issued or could have issued such instructions as Lee-Khak-Un described either to Lee himself or to any other persons like Lee-Hak-Un.” (Stalin and Kaganovich…., p.277.)

“The rise of a spontaneous Christian movement in foreign countries”

But let us go back several years. On 29 February, 1925 at a meeting of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik), after considering “the Politburo Commission project to resolve the question of active reconnaissance” the resolution “In regard to Razvedupre” [reconnaissance…] was unanimously approved. The first point in the document marked “top secret” stated:

“Active reconnaissance (by diversionary and military-subversive groups and others) in the first period of its existence was a necessary addition to our military endeavors and performed the military missions that were given it by the party central.” (Lubianka…., p.98.)

It is further stated that “with the establishment of more or less normal diplomatic relations with the countries that border the USSR” alleged “directives have been issued more than once to curtail active missions” but due to “the rise of spontaneous Christian movements in foreign countries out of which cadres of diversionary intelligence-gathering groups were formed” whose mission it was to complicate the management of those groups to such an extent that a whole series of incidents took place that “caused harm to our diplomatic work.” Thereafter the Politburo of the Central Committee issued an order: “active intelligence work in its traditional form (making connections, providing supplies and leadership through diversionary groups sent into the territory of the Polish Republic) is to be liquidated.” The order further states that “as of today our active militias should not be present in any country, they should not engage in armed action or be receiving direct resources, instructions, and leadership from us,” and “all military and partisan missions, squadrons and groups, as long as it is politically prudent <……….> should be transferred to be in complete subordination of the Communist parties of the country...” All former “active reconnaissance groups as well as subversive military and diversionary groups” <…….> are to be liquidated” and in place of “traditional active reconnaissance groups” “special sites” will be established on the territory of the neighboring country, along with deeply hidden spots of opposition “to lay low and to prepare and if war breaks out to do damage at the front lines of the opponent.” Those “sites of opposition should be centers of information and preparedness. They have to be ready at the right moment to serve as platforms for military action” but under no circumstances “will they have any contact with the Party.” The Politburo directed that all the ousted supervisors of the “former active Reconnaissance Agency” must be immediately substituted and our side of the border zone must be cleansed of “active partisans who, as has been ascertained, cross the border on their own to fight.” It is further ordered that “they should be handled carefully and kept on a list of men to be used in case of war” and evacuated into the heart of the country. And in order that the “execution of all the ordered actions is painless and to avoid any dissatisfaction with the dissolution or degeneration of separate groups or individuals assigning appropriate sums of compensation is critical.” Establishing “a solid budget in an amount that will assure future wide ranging work and will guarantee the coordination and sustenance of jobs for all accomplices” is equally important. It has been decided that “changes in the ordered method of execution that might be required in special circumstances (for example, Bessarabia) can be implemented only in specific instances after a special review has been conducted and agreement has been reached by the Politburo.” This passage from a resolution of the Politburo catches special attention: “It is important to underline that the Polish government in this given case is not directly accusing us of anything, their relation with us is based on surmises. Therefore any verbal assault against us must be met with maximum defiance and resistance.” (Lubianka…, pp. 98-100.) […..]

From Poland to Ireland

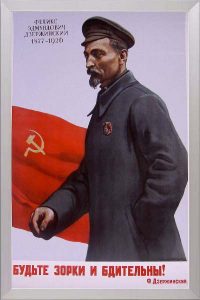

It all started on 5 January, 1925 when suddenly the representative of the OGPU of the USSR and a candidate to the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik) Felix Dzerzhinsky received an extraordinary note from a political representative of the OGPU in the USSR (and at the same time the chairman of the GPU and People’s Commissar of the Ministry of the Interior in Ukraine) Vsevolod Balitsky that soldiers of the Polish army have crossed the Soviet border near Yampol (presently a town in Khmelnytskyi Oblast), destroyed the headquarters of the second Yampol command post and broke through into the territory of the USSR. Moscow-Warsaw relations were far from warm at that time, but to destroy an entire outpost so openly?!

The Politburo was in shock. They even came to a conclusion: there it is - the Polish hostility, of which the Bolsheviks had forever warned us, has turned into aggression! Since at the time the “undefeated and legendary” Red Army was completely unprepared for war, a note was immediately dispatched through the NKVD to the Polish authorities in which it was stated that the Soviet side was ready to repair relations after what had happened through peaceful means. The Polish Ministry of Internal Affairs reacted to the note with visible surprise: what incident?! All the more since it soon became apparent that along the entire boundary with Poland nothing had happened: Polish troops had never crossed the border and the Soviet regiments did not shoot or attack anyone.

Citing the information that the Volyn province border security provided, the chief of GPU border security Nikolai Bystrykh sent the following report to Moscow:

“On the 5th of January, 1925 at 1:30 a detachment of the Polish army consisting of 40 infantry troops and three cavalry carried out an attack on the headquarters of the second command post of the Yampol division and outpost No. 5 that is located within the grounds of the headquarters in the settlement of Sivki 7 km north of Yampol. The attack was repelled. On our side the head of the outpost, Dikkerman, was wounded and on the Polish side one man was killed. On the 5th of January at 1:30 the border guards on hourly rotation, Zvuhin and Trubitsin, observed the movement of approximately 40 Polish infantry troops and three cavalry who were riding in front. After noticing a roundabout the Polish soldiers began shooting and without slowing down crossed our boundary and attacked our headquarters. The building that housed our headquarters was shot at with rifles, and up to thirty bombs were hurled into the space right next to the building. Upon hearing the commotion the head of the outpost together with sixteen Red Army soldiers came out, started to repel the opponent and was wounded. The Polish soldiers succeeded in breaking into the apartment of the head of the outpost (they thought it was the outpost). A subordinate who was in the apartment killed the first Polish soldier who entered. The Polish soldiers took the body away. The hat that fell off the dead soldier serves as material evidence of the incident. The death of the Polish soldier and the determined counterattack of our boundary guards forced the attackers to retreat…” (Border Troops of the USSR 1918-1928. Compilation of Documents and Data. M,. Nauka Publishing, 1973, pp.515-516.)

The attackers did not stop attacking nor did they retreat. They succeeded in breaking into Soviet territory where they disappeared without a trace. In the process they exhibited exceptional military decency: they did not abandon their dead friend, they took his body and did not leave any evidence except for the hat which in reality they had no way of attaching to the body. But then was there really a body? Not to mention that in the heat of the night battle it is unrealistic to believe that two corporal’s stripes could have been noticed on the epaulettes of the purported dead soldier.

The reaction of the “Iron Felix” was sharp. Rightly distrustful of the report he immediately ordered his deputy Henrich Yagoda:

“It is imperative to conduct an investigation on location. It is important to completely clear up the motives and reasons for the Polish action. This is a very serious problem.” (F.E. Dzerzhinskyi – Chairman of the VChK-GPU 1917-1926. Compilation of Documents. M., International Fund for Democracy, 2007, Document No. 981)

The Politburo Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik) convened an extraordinary meeting on 8 January, 1925 specifically for the thorough examination of the “Yampol incident” and appointed a special troika to conduct a detailed investigation. Inasmuch as nothing was cleared up another extraordinary meeting of the Politburo had to be convened on 27 January 1925 about the same affair. An unusual order Dzerzhinskyi issued to Yagoda is dated with the same day: “It is imperative that we interrogate the border guards at the center as well as there at the border about everything they know about gangs (ours) and about the goings on at the reconnaissance sector and all those department supervisors who came to the meeting. The request is most urgent and most important.” (F.E.Dzerzhinskyi, Chairman of the VChK-GPU. 1917-1926…, Document No. 987.)

“Our gangs” is not a slanderous term that was aimed at the chairman of the OGPU. At that time Dzerzhinskyi knew absolutely for sure that it was not the Polish soldiers who had attacked the outpost, it was… our own, our military intelligence special operations unit dressed in the uniforms of the Polish army, executing a diversionary-terrorist act. It was the intelligence unit from RCCA headquarters! It was those subversive reconnaissance agents that Dzerzhinskyi, without hiding his anger, "applauded" when he said "our gangs.” He wrote a revealing letter to the head of the Ukrainian GPU Vsevolod Balitskyi:

“Dear comrade Balitskyi! The irresponsible actions committed by the reconnaissance unit, dragging us into conflict with neighboring governments must be curbed. What happened in Yampol has demonstrated that anti-Polish gangs exist on our territory just as with our assistance gangs work on foreign ground. Please send me as soon as possible any pertinent material you have on the matter and in addition send me the following:

1) Information about the gangs, the numbers (how many there are), their locations, on our side of the border as well as on their side. Their weaponry. What they represent, what is their ideology, how well disciplined are they?

2) Whom do they supply with information, to whom are they subordinated, to which group, to whom in the border zone, in Kyiv, in Kharkiv, in Moscow?

3) Which organization handles them in the cities and on location? What is the line of authority?

4) What are the reconnaissance unit and its party organs like where you are? What ideology drives them? Provide character analysis and evaluation of the personnel; who gives them orders?

5) What are the mutual relations with us and with the border troops? What procedure do our border guards follow regarding border crossing?

6) Your recommendations and your relations with the gangs and their activity as well as with the reconnaissance unit. Should they be liquidated and how should that be done? Is it possible and is it necessary to send away the gangs into the heart of the country – where? Is it possible the gangs can turn against us if one of them is thrown to the other side of the border.

Please take care of the matter personally. Do not make copies of my letter. Return it to me with your answer and enclose all the material I need for the Politburo Commission of which I am a member.

Greetings, F. Dzerzhinskyi

P.S. Send me detailed information about the gangs in Yampol and tell me what, actually, the commission has revealed.” (F.E. Dzerzhinsky Chairman of the VChK-GPU. 1917-1926…, Document No. 988.)

In the course of his investigation Felix Dzerzhinskyi learned a lot of interesting things. He learned, for example, that military intelligence had conducted those operations not only right under his nose, they had been conducted since March, 1921, when the Riga Peace Treaty was signed between Soviet Russia and Poland. In fact the reconnaissance unit unrolled its so-called “active intelligence operations” right after the signing of the treaty. A massive operation was launched in Poland involving well-trained subversive terrorist groups and regiments. They were not independently run operations, they were special forces performing special operations sanctioned on the level of the Politburo. The Kremlin was hoping that in deploying professional subversives and terrorists Poland would be so destabilized that eastern Poland would simply fall into the hands of the Bolsheviks.

The commanding personnel for those operations were selected from career military officers of the Red Army who had battle experience as well as from experienced political-managers-chekists [CHEKA is the old Soviet secret service] who had schooling in party leadership. The skeleton of the special operations units was formed and armed on the territory of Byelorussia and after completing special training exercises they were deployed in the eastern regions of Poland making use of specific “windows” along the border. Pretending to be popular people’s “warriors to rid wrongs” the Soviet diversionists murdered individual policemen and attacked police stations, overran and robbed passenger trains, drove trucks off roads into ditches, exploded steam engines and bridges, robbed and burned the homes of landowners and killed the landowners (as was instructed), civil servants, Catholic and Orthodox priests, heads of counties; they annihilated homesteads and destroyed “traitors”, they conducted prison raids liberating “battle comrades” and robbed banks – all just part of conducting a “war of liberation,” of course. When possible the “rebels” organized meetings in villages at which they heatedly threw out a challenge to the Byelorussian Christians to oppose the Polish “lords.” […..] (Sm.: Vaupshasov, S.A. At A Troubling Crossroad. Notes of a Chekist. M., Politizdat, 1974, pp. 95-139.) Noteworthy is the fact that even though the operation followed the Reconnaissance Division’s line, in the end all the chief participants in “active intelligence gathering” turned out to be members of the Cheka information office.

In the period from April, 1921 through April, 1924, Polish authorities registered 259 border crossings committed by the military reconnaissance regiments of the RCCA. Between April and November, 1924, those “active intelligence gathering” regiments conducted no less than 89 military operations on a massive scale in western Poland to destabilize the situation. [……..] And reconnaissance special operations were not curtailed even after the incident in Yampol with the subsequent resolution of the Politburo to liquidate those “active reconnaissance operations in their current form and use.” Between March and May, 1925, the “rebels” conducted 59 military operations in western Byelorussia, from June through August of the same year, 50 more operations and altogether between December 1924 through August, 1925, Soviet subversive forces conducted 199 military operations. (Sm.: Kolpakidy A.I., Prokhorov D.P. The GRU Empire. An Outline of the History of Russian Military Intelligence. Volume II. M., “OLMA-PRESS,” p. 127.)

The truth is, the diversionary squads and terrorists were not able to achieve their ultimate goal with their operations. The hoped for people’s revolution never happened in western Byelorussia or in western Ukraine. It was one of those Soviet subversive groups squeezed at the border by the Polish Korpus Ochrony Pogranicza (Border Security Corps) that had attacked the Soviet outpost. What for? It could be that the rebels thought the gloomy outpost was Polish or it could be that the Soviet border guards saw a movement of strange men wearing Polish uniforms and opened fire.

The “Yampol incident” did not put an end to “active intelligence” operations. They were continued in full force in the Far East: in the years 1929-1930 they were utilized in Afghanistan, from 1933 to 1946 in western China (Szinian). And on June 16, 1927 the chairman of the RVC of the USSR People’s Commissariat in military and naval affairs Klym Voroshilov completely reversed things in the Politburo of the CC VCP(b) with an interesting proposition: follow the script the GPU and reconnaissance units of the RCCA had in the first half of the 1920s as far as organizing “active reconnaissance” brigades on the territory of Poland and without delay deploy Soviet subversive brigades in …….Ireland! After a week of reviewing “Comrade Voroshilov’s Proposition,” the Politburo came to a resolution:

“ […..] As far as preparation in the department of diversionary tactics it is imperative to begin preparations under the supervision of a commission appointed by the Politburo consisting of comrades Kossior, Piatnytskyi, Yahoda, and Berzina. In two weeks a plan and methods of operation must be worked out and necessary supplies to do the job must be procured as soon as possible.” (Lubianka…, pp. 134-235; 795.)

It is not that hard to figure out why Voroshilov proposed to plant subversive groups specifically in Ireland. 23 February, 1927 the minister of foreign affairs of Great Britain Joseph Austin Chamberlain exchanged notes with the Soviet authorities about curtailing anti-British propaganda and subversive activity against the British Empire, and in May of that year diplomatic relations between Great Britain and the Soviet Union were broken. Moscow seriously believed that the real issue was that war was being planned against the USSR. They believed Great Britain was leading the effort, and the USSR was unprepared to defend itself – at that time the Red Army was actually not battle ready. That was what had provoked Voroshilov to come up with the scheme to try to get to the “damn British”- at least through diversionary groups, via Ireland. The affair ended in failure: the Soviet “military reconnaissance” units had no occasion to operate in Ireland.