In late October, the Canadian Parliament's Standing Committee on Public Safety convened to examine Russian disinformation's influence in Canada. The hearings, prompted by pressure from Ukrainian-Canadians, were triggered by controversy over the documentary "Russians at War" by former RT producer Anastasia Trofimova.

Despite Canada's 2020 ban on RT, Trofimova secured $340,000 from the Canada Media Fund for her film, which advanced pro-Russian narratives about the war in Ukraine.

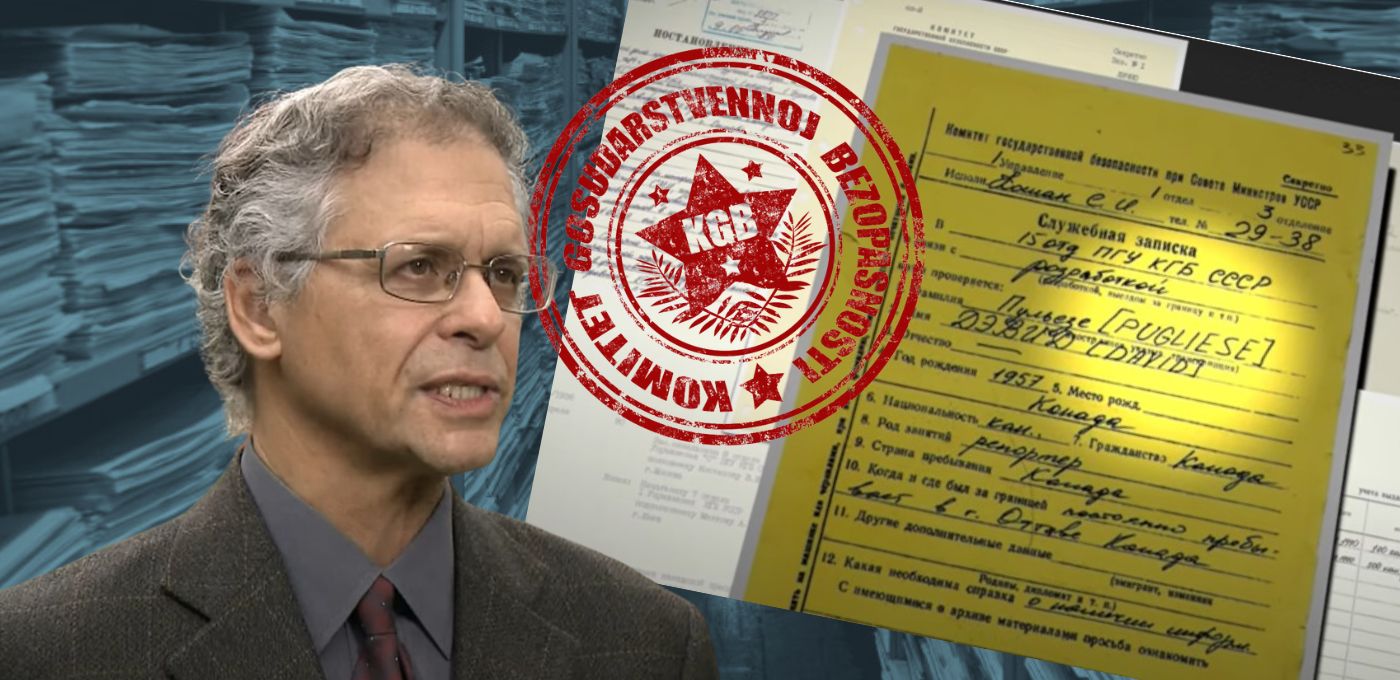

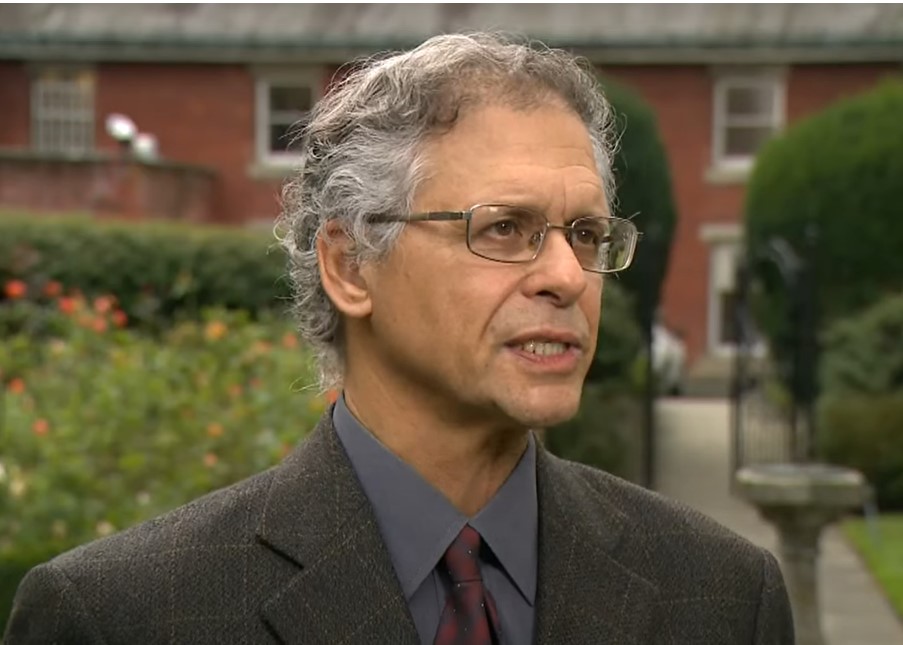

The hearings expanded dramatically when former minister Chris Alexander presented evidence of deeper Russian influence operations. He accused veteran Ottawa Citizen journalist David Pugliese of Soviet and potentially Russian intelligence ties, producing KGB documents that allegedly tracked Pugliese since 1982 under the codename "Stuart."

These tensions reveal growing concerns about Russian propaganda's reach in Canada. Let’s delve into the structure of this disinformation network and its impact on the Ukrainian community.

Agent “Stuart": The KGB's target in Canadian media

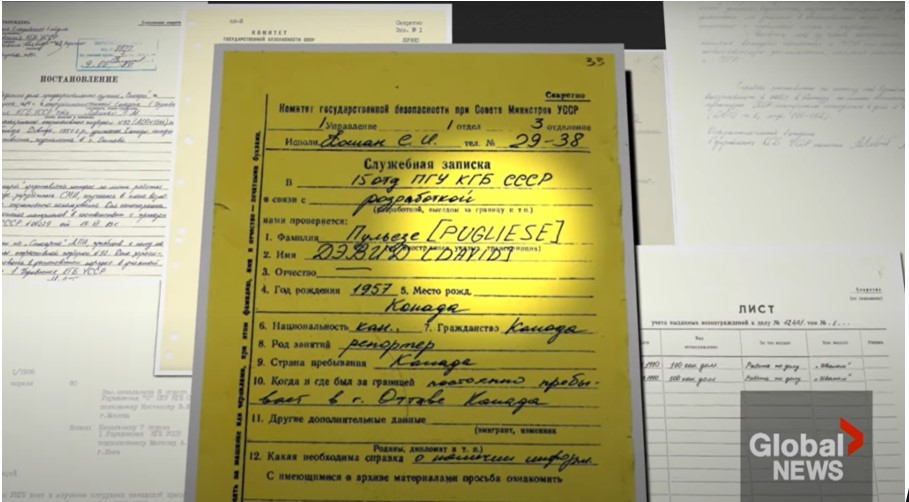

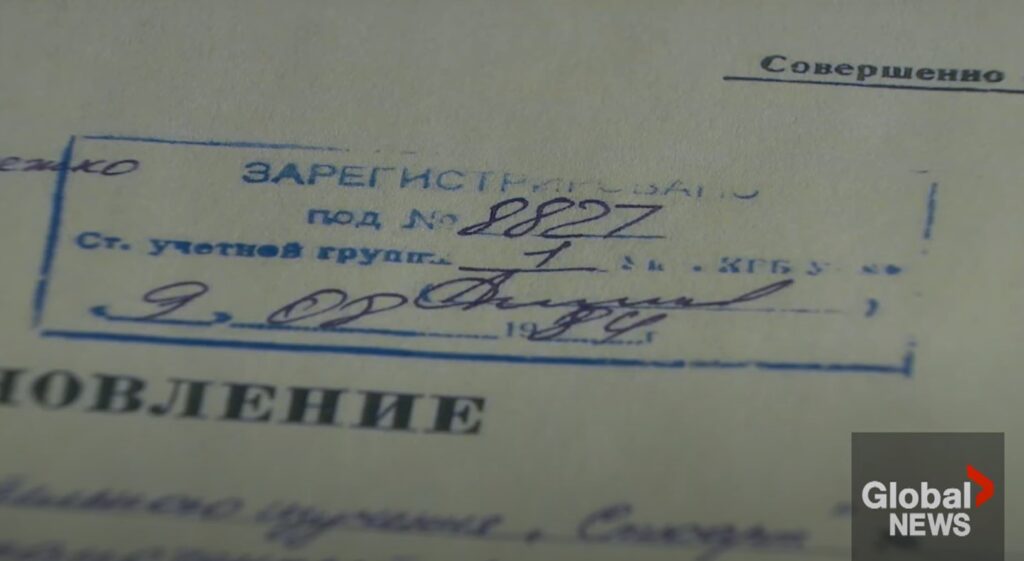

Eight documents presented to the committee by Chris Alexander were allegedly uncovered in Ukraine's KGB archives. The archives, opened by Kyiv in 2015, represent the world's largest unclassified collection of KGB documents.

According to Alexander, two independent experts and several historians confirmed the documents' authenticity, though they remain subject to further verification. These documents reportedly show that the KGB had David Pugliese under surveillance since 1982, viewing him as potentially influential in Canadian and American media.

The surveillance allegedly began after a KGB agent known as Ivan, met Pugliese at a 1982 public lecture about the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

A document from 6 April 1990 notes Pugliese's position at the Ottawa Citizen newspaper, prompting the KGB's 1st Department to seek Moscow's permission to use him for their foreign intelligence division's interests. A subsequent note from 20 June 1990 confirms establishing contact between Ivan and "Stuart."

Alexander suggests these connections likely persisted beyond the USSR's collapse, continuing under Russian intelligence. Pugliese denies being recruited by the KGB.

Agent "Stuart" against Ukraine

In his parliamentary address, Chris Alexander was direct about Russian propaganda: "Canadian officials have underestimated its influence." This concern follows a series of foreign interference revelations in Canada: Chinese attempts to influence elections, the expulsion of Indian diplomats over an assassination plot, and the exposure of Tenet Media accepting Russian state funds to spread Kremlin narratives.

Against this backdrop, investigating Russian disinformation in Canada seemed logical.

Pugliese's four-decade career has focused on military and security affairs, particularly scrutinizing the Canadian Armed Forces, military procurement, and misconduct cases. He's emerged as a prominent critic of Canada's Defence Ministry and has written extensively about alleged "fascists" in Ukrainian and Baltic communities.

Despite the 1985 Duchesne Commission's exoneration of the Galicia Division -- a World War II Ukrainian military unit that fought against the Soviet Union and was later absorbed into the Nazi SS -- Pugliese has continued raising allegations about its wartime conduct. He published three articles on the topic last September alone and was among the first to report on Yaroslav Hunka, a Galicia Division veteran, attending Parliament during President Zelenskyy's visit.

Analysis of Pugliese's work shows that approximately one in ten articles addresses "Ukrainian Nazis," while notably absent are pieces about Russia's invasion of Ukraine or its Arctic threats to Canada.

"Pugliese uses the war in Ukraine to criticize Canadian military, government, and NGO support for Ukraine, distorting facts in ways that harm the Ukrainian-Canadian community and undermine Ukraine's position," says Lesya Granger, President of Mriya Aid, a Canadian organization supporting Ukraine since Russia's invasion.

Agent "Stuart" and his academic friends

David Pugliese isn't operating in isolation. Ivan Katchanovski, a University of Ottawa professor, has promoted similar narratives about "Ukrainian Nazis" and the "state coup" in Ukraine since 2014. Despite sanctions against RT, Katchanovski regularly comments on this pro-Kremlin outlet, and Pugliese frequently cites his work.

Trending Now

Scott Taylor, another military researcher focusing on "Ukrainian fascists," maintains unimpeded access to Moscow while promoting narratives like "Crimea historically belongs to Russia" and "Ukraine cannot win this war." Both Taylor and Pugliese are established Canadian journalists with privileged access to military affairs coverage, publishing in influential outlets like Ottawa Citizen and The Hill Times.

"These propagandists primarily accuse Ukraine and Ukrainians of being Nazis, racists, and anti-Semites. This creates pressure to reduce Western support for Ukraine, divides Ukrainians and Jews, and revives the myth of the peaceful, anti-fascist Soviet Union," explains Canadian historian and Jewish-Ukrainian descendant Alik Gomelsky.

He believes the Soviet KGB established one of its largest "networks" in Canada, which continues pushing anti-Ukrainian narratives.

"The pattern is clear: historians and professors produce anti-Ukrainian works under academic freedom, journalists then reference these works, and propagandist activists spread them to the masses," Gomelsky notes.

He has identified at least 20 "researchers of Ukrainian fascism" in Canada, ranging from public figures to marginal online amplifiers. Their narratives intensify around World War II commemorative events, the Babyn Yar massacre anniversary, and crucial political moments such as Canada's decisions on military aid to Ukraine or high-level diplomatic visits.

Moscow's Canadian network

Russia's disinformation in Canada extends beyond Ukraine to target Western values, NATO, and democracy itself.

"The pro-Kremlin activist network in Canada is extensive. When I challenge one publicly, it triggers a wave of hate. The network includes former diplomats who sit on Russian or pro-Russian organizations' boards," says Markus Kolga, founder of Disinfowatch and a 15-year researcher of Russian disinformation.

Kolga, who has Estonian roots and studied Soviet occupation history, also testified at the parliamentary committee. He, too, became Pugliese's target, accused of "whitewashing Nazis."

"Historically, Baltic peoples in Canada have also been accused of fascism. The narrative labels anyone who fought against the Soviet Union as an enemy of democracy and Canada," confirms Gomelsky.

What's particularly concerning is that openly biased academics like Ivan Katchanovski, Michel Chossudovsky, and Radhika Desai maintain their status as "respected researchers" rather than being recognized as Kremlin propagandists. Desai even participated in Putin's Valdai Club last year - an annual propaganda forum where the Russian president meets with carefully selected foreign academics and journalists to promote Kremlin narratives.

The public revelation of Pugliese's alleged Soviet intelligence ties reveals more than a scandal—it exposes the reach of Russian influence operations and their tactics in recruiting Western journalists.

Despite Pugliese's consistent use of Russian narratives about Ukraine, his positions are often dismissed as mere journalistic opinions. The key question remains unresolved: Is he actively working with the Kremlin, or unwittingly serving its interests? The answer awaits a thorough investigation.

As this case demonstrates, dismantling Russia's influence networks presents a significant challenge for Canada and its Western allies.

Related:

- What makes Russian spies tick? World’s largest declassified KGB archive, in Ukraine, tells all

- Ukrainians discover stories of repressed relatives in newly opened KGB archives

- The complicated truth about Yaroslav Hunka

- Kremlin planned to destabilize Ukraine in the early 1990s by smearing “all forms of nationalism,” KGB file reveals