Is Europe ready to back up its talk about security with real action? This matters now as Donald Trump is pushing for a quick end to Russia’s war in Ukraine. Media reports suggest one proposal involves freezing the conflict along current battle lines, with Western security guarantees preventing Russia from regrouping and attacking again.

Trump wants Europe to take on this security role, maybe by having European forces watch over a buffer zone along the front line. But even after three years of Russia's invasion - part of a longer ten-year war - Europe's response is mixed. Some countries have stepped up their military spending, while others hold back. Meanwhile, “the axis of evil” - China, Russia, North Korea, and Iran - keep building their forces, and Trump's peace plan would likely put more costs on Europe.

As Trump returns to power, Europe faces a key question: Are NATO's European members taking these warnings seriously? Let's look at what's really happening.

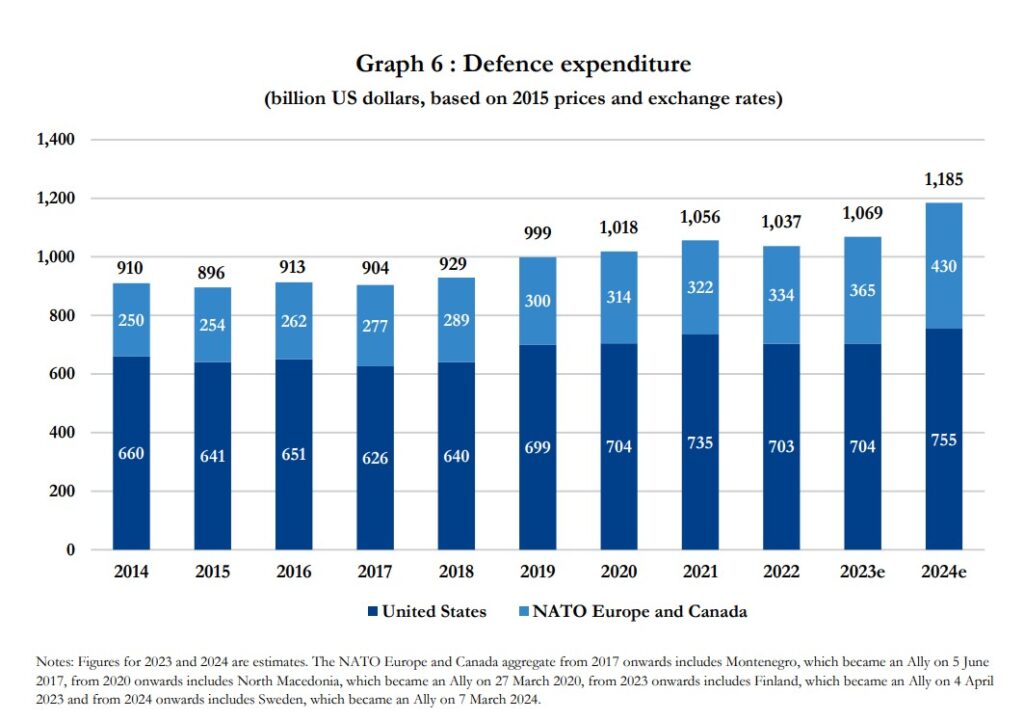

Who shoulders NATO's budget?

Between 2014 and 2021, the US was the largest contributor to NATO in billions of US dollars. While the volume of contributions varied between the years, the US always chipped in the most, during Trump's first tenure included.

Back then, one of the main tasks for the former NATO chief Jens Stoltenberg was to bridge the understanding between Trump’s administration and European leaders as Trump confronted NATO allies for failing to meet their target spending levels.

“All allies are stepping up, doing more in more places in more ways,” Stoltenberg said as he unveiled NATO’s 2017 annual report.

However, Trump remained critical, particularly of Germany. The 2018 video encapsulates the tensions between the US and other NATO members at the time.

In a fiery exchange with Stoltenberg, Trump, who’s sitting with former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo by his side, rejects Stoltenberg’s appeal that the Allies have started investing more in NATO, saying that Germany is captive to Russian gas while praising Poland and other countries who discarded the Russian fossil fuels.

“It’s very sad that Germany makes a massive oil and gas deal with Russia where we’re supposed to be guarding against Russia, and Germany goes out and pays billions and billions of dollars a year to Russia,” Trump said, adding that if Berlin wanted to, it could increase the defense spending tomorrow.

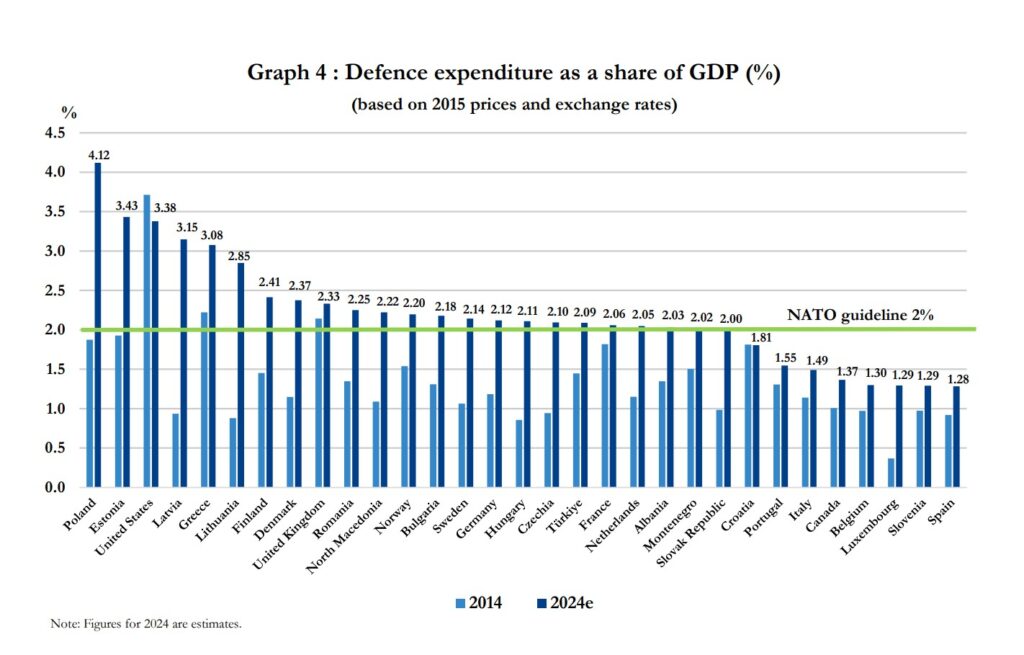

Big economies fall short of NATO's 2% target

The 2024 data reveals a sobering reality: neither Stoltenberg's appeals nor Trump's warnings significantly moved European defense spending, even after nearly three years of Russia's full-scale war in Ukraine.

At a glance, the majority of NATO member states are now meeting the baseline demand of 2%, compared to 2014, when only three countries – the US, Greece, and the UK – did so. Just seven European countries, including Spain, Slovenia, Belgium, Luxembourg, Italy, Portugal, and Croatia, are still missing the target.

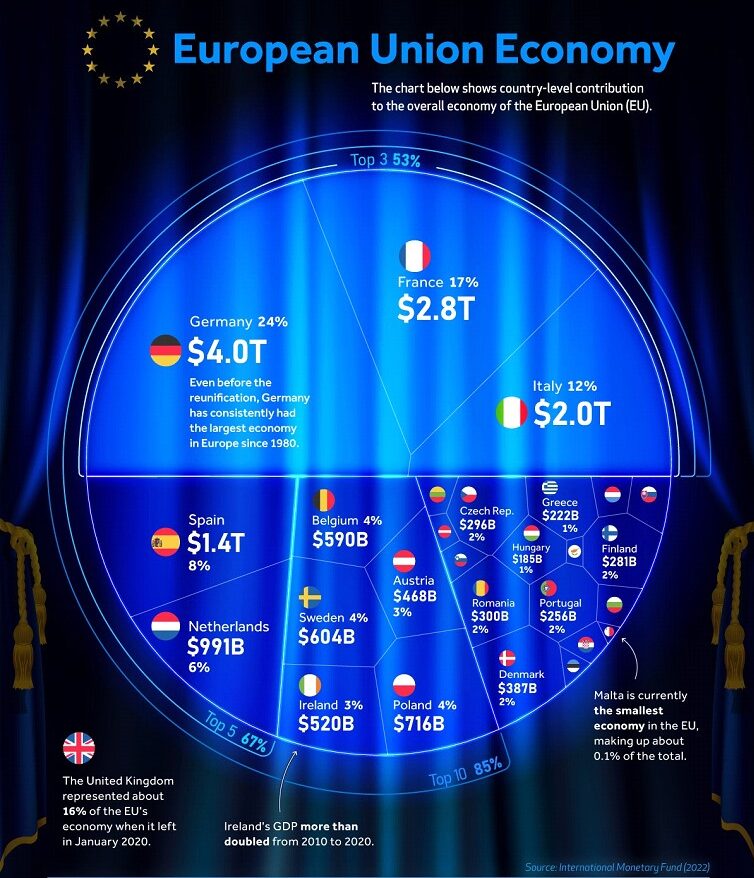

However, the graph tells a different story if you factor in the size of EU economies.

Viewed from that perspective, European powerhouses like Italy ($2.0 trillion), Spain ($1,4 trillion), and Belgium ($590 billion) are not only missing the 2% target but are also depriving the Alliance of a tangible chunk of contributions that frontrunners like Estonia or Lithuania simply cannot offset.

Trending Now

Notably, Spain, Belgium, and Slovenia (spending just 1.29%) were also reported by Politico Europe to oppose Ukraine's NATO membership.

While the two largest European economies, Germany and France, are now spending 2.06% and 2.12% of their GDP, respectively, the caveat is that Germany, in particular, failed to hit that target for almost three decades, reaching the level of 2% only in early 2024—two years into Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine and a decade since its annexation of Crimea and invasion of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts.

This is despite Germany being the richest economy in the EU ($4 trillion).

The bright spots? Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Greece, Lithuania, Finland, and Denmark have significantly boosted defense spending. Poland's contribution carries special weight as a top-10 EU economy. New NATO members Sweden (joined March 2024) and Finland also make substantial investments.

Trump hands Europe the bill, but peace might cost more

While NATO members are spending more on defense, the brutal reality of Russia's war in Ukraine suggests this still falls short. Former Ukrainian Foreign Minister Pavlo Klimkin argues that while 2% of GDP might have sufficed in peacetime, today's target should be at least 5%.

Russia's military spending underscores this urgency. In September, Bloomberg reported that Russia plans to boost defense spending to 13.2 trillion rubles ($142 billion) in 2025 from the 10.4 trillion rubles projected for this year.

Furthermore, reports suggest that Trump's potential peace plan for Ukraine might shift more financial responsibility to Europe. One of the options reportedly under consideration involves establishing a buffer zone in Ukraine guarded by EU and British troops—a move that would require substantial European financing to ensure Russia doesn't breach any ceasefire agreement. Such an arrangement, if implemented, would likely demand even higher spending from NATO members, whether through the Alliance or individually. So far, little has been indicated that this is the case.

In response to evolving security challenges, Poland, NATO's highest GDP contributor, has begun building a "coalition of the willing" to reduce US involvement in Ukraine's support. This group includes Baltic states, Nordic countries, the UK, France, Canada, and the Netherlands. However, questions remain about members' commitment - notably, Canada, with its $2.14 trillion GDP, still only spends 1.37% on NATO needs.

Recent diplomatic moves have added to the uncertainty. Emmanuel Macron’s unexpected handshake with Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov at the G20 summit in Brazil raises questions about certain European states' true intentions as the peace talks loom.

Given these developments, one thing remains likely: any peace push by Trump’s administration will only postpone the war in Ukraine, not resolve it. And Europe must bear that in mind.

Read more:

- Russia-Ukraine war: Why starting the clock at 2022 misreads Putin's strategy

- Ukraine builds a bridge to Trumpland

- Why Trump's path to beating China runs through Kyiv