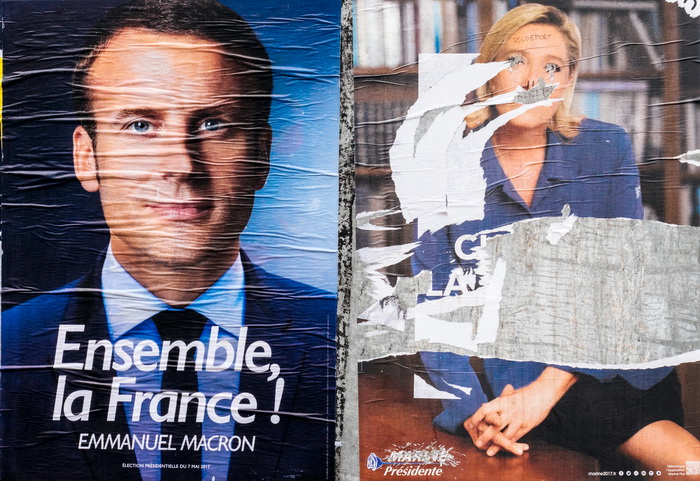

From Lisbon to Kyiv, many capitals across Europe breathed easier on the night of Sunday, 24 April, as results from the 2022 French election confirmed that Emmanuel Macron had won a second term as President of the Republic. Coming ahead of right-wing challenger Marine Le Pen with 58.8% of the vote, the incumbent has secured another five years in office in which to continue the recent resurgence of purpose which has galvanized both the European Union and NATO in the wake of Russia’s assault on Ukraine. Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi declared the result as “great news for all of Europe,” while European Council President Charles Michel tweeted,

“In these turbulent times, we need a strong Europe and a France fully committed to a more sovereign and strategic European Union. We can count on France five more years.”

While the contest between the two candidates presented a rematch of the 2017 election, the 2022 campaign was a closer race than either President Macron or many analysts initially anticipated. The first round percentages on 10 April presented a shake-up in French politics, underscoring an electoral divide that, in coming years, threatens to widen. While the president scored 27.9% of the vote, Le Pen attained a close second with 23.2%. In the second round, Le Pen secured 41.2% of the electorate, marking the best ever result for the far-right in a French presidential election.

Right-wing nationalism rebranded

Le Pen gained in the polls by toning down much of the fiery rhetoric for which her party, the re-branded National Rally, has long been known. She also revised her stance on divisive issues previously part of her platform, such as pulling France out of the Eurozone. This makeover was aided by comparisons to Éric Zemmour, a polemicist whose ideology bends even further to the right (he has twice been convicted of incitement to racial discrimination and racial hatred). As explained by political scientist Luc Rouban, Zemmour “made [Le Pen] seem more moderate” while he has “taken up themes of the National Front of old, focusing on identity and immigration.”

Softened rhetoric notwithstanding, the menace of a Le Pen presidency was repeatedly articulated by her opponents. Edouard Philippe, who served as Prime Minister under Emmanuel Macron, bluntly informed Le Parisien that electing the National Rally leader would head the nation down a dark path: “Things would be seriously different for the country…Her program is dangerous.” President Macron echoed those sentiments in a rally in Marseille, stating, “The far-right represents a danger for our country. Don’t just hiss at it, knock it out.”

Internationally, the peril was recognized as an acute threat to the post-WWII, rule-of-law and democratic liberal traditions of the European continent. In an essay published by Le Monde, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, and Portuguese Prime Minister António Costa highlighted the existential crisis facing Europe’s future at the ballot box:

“It’s the election between a democratic candidate who believes that France is stronger in a powerful and autonomous European Union and an extreme-right candidate who openly sides with those who attack our freedom and democracy, values based on the French ideas of Enlightenment.”

Opposing European views

Emmanuel Macron came to office in 2017 on a centrist and pro-European platform. Left-leaning voters, however, point to the string of pro-business initiatives, the economic and tax policies favoring the well-off, the labor law reforms, and the tightened immigration legislation which the government has enacted over the last five years—as well as the brutal response to the Gilets Jaunes protests—and cry foul. Such is the disillusionment and disgust among the left with the En Marche President that the estimated tally for second-round abstentions reached 28.2%, the highest level since 1969.

"I am sincerely grateful to our partners for the assistance and unwavering support in these hard times. Our Friendship is our Victory,"–Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine Valeriy Zaluzhnyy, posting this video https://t.co/dUaGGGUwOi pic.twitter.com/IM3PYTE1gM

— Euromaidan Press (@EuromaidanPress) April 25, 2022

While the President has promoted a neo-liberal agenda domestically, on the international stage, he champions the network of integrated alliances underpinning the post-WWII international order. He has long advocated the idea of a common European defense budget, underscoring the need for a European “rapid response force,” and has emphasized the urgency of formulating an integrated European asylum system. Speaking at the Sorbonne in 2017, he stressed the need for a strengthened Europe to work together, proclaiming,

“The only path that assures our future is the rebuilding of a Europe that is sovereign, united and democratic.”

In January 2022, France took over the rotating presidency of the European Union. Under its title, President Macron crisscrossed the continent in the weeks preceding the Russian invasion of Ukraine, engaging in EU and NATO emergency meetings with his European counterparts, and even traveled to Moscow in an attempt to deescalate the Kremlin’s intensified hostilities.

Marine Le Pen offered voters the anti-Macron platform. Staunchly nationalist, she has previously supported a so-called “Frexit” in which France, like the UK, would leave the European Union. In her party’s 2022 manifesto, her “France First” policy granted priority for French citizens regarding internal questions of social housing, job applications, and social benefits, an initiative directly contravening EU laws regarding citizens’ freedom of movement.

Calling to reduce France’s EU budget contributions, she has insisted that French laws should have primacy over EU edicts and directives. She also supports the re-establishment of French border controls, a move directly contravening the Schengen agreement, as well as the decoupling of the Franco-German alliance at the heart of the European project. In the debate held a few days before the second round of the election, she angrily dismissed the very concept of a united European identity:

“There is no European sovereignty because there are no European people.”

Additionally, while Le Pen has repeatedly stressed her support for the Ukrainian people, her close ties to the Kremlin were heavily highlighted during the campaign.

In 2014, she recognized Russia’s referendum on the annexation of Crimea as legitimate, stating that the territory “had always been Russian,” In October of the same year, she took out a €9m loan with the now-defunct Russian-controlled FCRB bank. According to a 2019 study by the Alliance for Securing Democracy at the German Marshall Fund, FCRB had provided “a key cog in Moscow’s attempt to swing political contests overseas.” The study specifically focused on Le Pen’s party and concluded that FCRB had been a “vehicle for money-laundering by corrupt elites on a massive scale,” stating that the loan constituted “Russian state-sanctioned interference in the Western political system.”

The fact that the loan has yet to be repaid effectively leaves Le Pen indirectly indebted to the Kremlin, a compromised position should she ever head Europe’s second-largest economy. Le Pen has often voiced her long-standing regard for the Russian president. At a press conference held in mid-April, she clearly cemented her allegiances by announcing that, as President, not only would she remove France from NATO’s integrated military command, she would also seek “a strategic rapprochement” with Russia once the war in Ukraine was over.

Closer ties to the far-right authoritarian leaders

While the 2022 election results ensure that this particular far-right candidate does not enter the Élysée, many analysts stress that the result should not be understood as a permanent victory.

Instead, many are warning of it as a further step in the legitimization process of nationalist, extreme-right political parties. The fact that the traditional center-left and center-right parties no longer play a major role in France’s political sphere (gaining only 6.6% of the first-round vote between them), further highlights the populist, right-wing swing of the populace.

Marine Le Pen is not vacating French politics, which means she will continue to influence the European cultural landscape. An investigation of the National Rally’s 2022 campaign brochure reveals the ideology underpinning the party’s platform. On page 3, a collection of photographs depicts Le Pen posing with leaders and heads of state in an effort to underscore her geopolitical clout.

The picture which received attention during the campaign was the one presenting Le Pen standing with Vladimir Putin. Yet the other photographs grouped in the brochure were equally revealing, for they amounted to a global roll-call of right-wing, authoritarian strongmen and nationalist eurosceptics: Viktor Orbán, Matteo Salvini, Idriss Déby, Michel Aoun, and Janez Janša. A brief overview of these individuals provides an insight into the specific political associations the National Rally chose to illustrate its platform:

- Viktor Orbán, Prime Minister of Hungary

As Europe’s longest-serving head of state, Orbán has close ties to the Kremlin and recently won his fourth term in office. His government’s curbing of democratic norms, a crackdown on journalistic freedoms and independent media, restrictions of civil liberties, and passage of anti-immigrant discriminatory laws has led to Hungary being listed as only “partly free” by Freedom House. Orbán declared the country an “illiberal democracy.” In 2011, his Fidesz party drafted a new constitution that centralized executive power, cutting the number of Parliamentary seats by nearly half to 199. Accounts of his funneling of EU funds to political allies have led to accusations of kleptocratic cronyism.

- Matteo Salvini, former Deputy Prime Minister of Italy

Among the first to congratulate Orbán on his recent re-election, the leader of the populist Northern League is renowned for his hardline conservative views. His anti-immigrant stance led to the Italian senate twice authorizing a trial against him after he blocked the docking of a migrant ship while he was Interior Minister. His protectionist and eurosceptic rhetoric has included calling the euro “a crime against humanity.” In 2017, Salvini signed a cooperation agreement with United Russia, and he has praised the Russian president as “one of the best statesmen.”

- Idriss Déby, former President of Chad

Until his death in 2021, Idriss Déby ruled Chad for three decades. Three years before he died, he introduced a new national constitution that would have allowed him to stay in power until 2033. Forbes magazine listed Chad as the most corrupt nation in 2006, and in 2020, the United Nations Development Program ranked the country 187 out of 189 in its human development index. In 2021, Ida Sawyer, deputy Africa director at Human Rights Watch, reported multiple cases of peaceful protesters being tear-gassed, along with the arrest (and reported beatings) of 112 opposition and civil rights activists.

- Michel Aoun, President of Lebanon

A leader whose violent war record stretches back to the Lebanese Civil War in 1989, Aoun (according to accounts by the US State Department) threatened to take American hostages and shower US diplomats with “a good dose of Christian terrorism,” leading the US to evacuate its embassy in Beirut. In a 2019 article entitled. “Lebanon’s Slow Shift into Russia’s Orbit,” Carnegie scholar Sami Moubayed detailed the draft of a 2018 never-finalized military agreement between Moscow and Beirut which would have “called for the opening of Lebanese airspace, airports, and naval bases for the Russian military, who are already stationed a stone’s throw away at Hmeimeem in Syria.”

- Janez Janša, (former) Prime Minister of Slovenia

A close ally of Orbán, Janša has led the Slovenian Democratic Party since 1993. Known for his authoritarianism, Janša has been implicated in various corruption scandals and was imprisoned following a bribery case involving a Finnish defense company. In 2013, the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption conducted an investigation that concluded that Janša repeatedly violated the law, failing to report assets. During his time as Defense Minister in the 1990s, multiple reports surfaced documenting his engagement in arms trafficking and bribery.

Renowned for his hard-line, right-wing, xenophobic rhetoric, he has been described by Der Spiegel as “the Slovenian Trump.” Analyzing Slovenia, Freedom House reported that “the current right-wing government has continued attempts to undermine the rule of law and democratic institutions, including the media and judiciary.” (Though overshadowed by the French elections, Slovenia also held elections on Sunday, with the green-liberal Freedom Movement winning the lead with 33% of the vote. Immediately afterward, the Social Democrats announced they would join a coalition government, thus securing a left-leaning parliamentary majority and removing Janša from power.)

Though some of the individual policies of these leaders differ (especially in regards to the war in Ukraine), the calculated alignment of Le Pen with these specific politicians in her campaign literature presents an intentional partnership with far-right nationalists, authoritarian strongmen, and hard-line eurosceptics who dispense with democratic rule-of-law. This is not unintentional. According to an article published by Le Monde on 31 March, “the changes [Le Pen] is planning to the constitution aim for the implementation of an authoritarian system.”

The message she is sending is clear.

Looking to the Future

A study published online on 25 March by Cambridge University investigates the truism that when centrist parties shift to the right in order to encroach on far-right platforms, they lure voters away, weakening the success of marginal right-wing parties.

Researching twelve European countries between 1976 and 2017, the study concluded the opposite result, however, with empirical evidence instead suggesting that such strategies “lead to more voters defecting to the radical right.” If, as the study reports, “accommodating policy shifts by mainstream parties…catalyze voter transfers,” resulting in the radical right becoming “the net beneficiary of this exchange,” it would behoove Western, left-leaning, democratic parties to refrain from mirroring the policies of their conservative opponents.

Over 40% of France voted for the far-right in the second round of this election. If Macron continues with neo-liberal policies (raising the pension age, hardening immigration policies), in five years, Le Pen, or another such candidate, may have even more legitimacy in the eyes of the French electorate. It may occur even sooner; French legislative elections are scheduled for June. In what is already being termed the election’s “third round,” the leaders of Zemmour’s Reconquete! party have called for a coalition of allies in order to sweep the parliament to the right.

Similarly, far-left populist Jean-Luc Mélenchon—who came in third in the first-round voting and whose platform overlaps with Le Pen’s nationalistic isolationism—has called for the French to elect him as prime minister. Should his anti-EU party win the legislative majority in June, President Macron would find himself battling a parliament led by a staunch eurosceptic who has repeatedly called for France’s complete withdrawal from NATO.

Related:

- The specter of Budapest Memorandum hangs over Ukrainian negotiations, darkens the future of global security

- Russia’s war on Ukraine marks start of new Cold War: foreign affairs analyst

- From Brexit to EU-kraine: 21st-century European unity relies on solidarity of former Soviet states

- 1 March 2022 marked the end of “neutrality” in Europe