Geoffrey Miller, International Analyst with the Democracy Project, and expert in foreign affairs and New Zealand policy, agreed to speak to Euromaidan Press for an exclusive interview. Based on his experience of working with embassies and diplomatic missions, he discusses the need—and limits—of diplomacy in the current Russo-Ukrainian War and in the changed 21st century geopolitical landscape. Explaining that practical diplomacy is “an active decision [and] choice” made by governments, he analyzes whether sanctions effect policy change and highlights the hard, realistic compromises of peace negotiations. He also evaluates the specifics of New Zealand’s evolving role in responding to the conflict.

Mr. Miller, thank you for agreeing to be interviewed. Beginning with a broad question: To what end does diplomacy exist, and how does it play a role in a situation like the war in Ukraine?

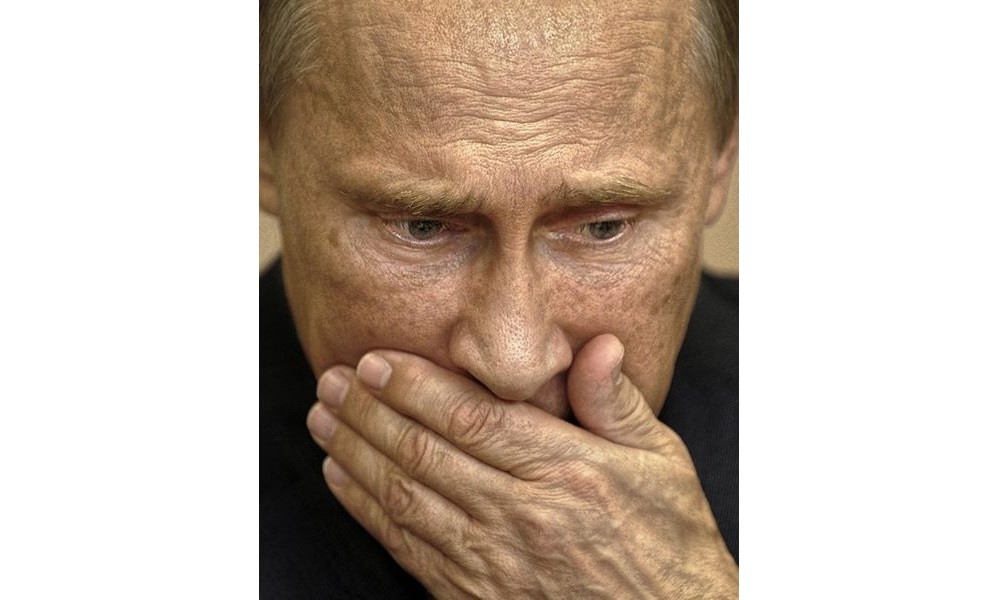

If “war is merely the continuation of politics by other means,” diplomacy is surely the only alternative. And there is no doubt that the West tried in the lead-up to the war, notably with numerous shuttle diplomacy missions by Emmanuel Macron and Joe Biden’s willingness to engage directly with Vladimir Putin through phone conversations.

The only question remaining is whether more could/should have been offered to Putin as an incentive to stop the war – such as Western recognition of Crimea and the breakaway republics in the Donbas region. This would have been a very hard sell to Western audiences and might have been dismissed as ‘appeasement’ – yet it seems that this will be a likely trade-off for any peace deal to end the war anyway, at a minimum.

Diplomats are not politicians, and diplomacy must be practiced regardless of which government is in power and which foreign policy is being pursued. How do all these aspects work in tandem, especially in crises situations like war?

The decision to engage in diplomacy is still very much an active decision by policymakers, and the very top diplomats are politicians –for example, the US Secretary of State who is often referred to informally as “America’s top diplomat.”

Perhaps another way of thinking of this is that diplomacy is a choice in the same way that war is. Diplomacy is not merely the absence of war. For another current example, think of the long-running, painstaking diplomatic efforts for the revival of the Iranian nuclear deal (or “JCPOA“).

The new German Foreign Minister, Annalena Baerbock, has stated that “eloquent silence is not a form of diplomacy.” What roles do prominence and moral authority play in diplomacy? For example, New Zealand earned a new global standing during the last two years with Jacinda Ardern’s handling of the pandemic. With such a newly raised global profile, is it incumbent on NZ to be seen as stepping up, diplomatically, to address global concerns like the war in Ukraine?

I agree with Baerbock’s statement – diplomacy is a choice. In my view, New Zealand does have capabilities as a small state that would allow it to play a greater diplomatic role internationally, with Ardern’s high international standing (as a result of pandemic leadership, but also her response to the 2019 Christchurch mosque attacks) being another factor. However, on Ukraine, New Zealand currently seems unwilling to take this approach.

Instead, the strategy being taken is a ‘West light” approach – with support for Ukraine but to a lesser degree than other Western countries. Partly this is probably because the current situation allows little room for nuance – it is a “with us or against us” moment and even typically neutral states, such as Switzerland and Finland, have joined the Western position.

New Zealand recently sent helmets and body armor, along with NZ$5m in aid, to assist in Ukraine’s defense efforts. How symbolic is this, and how necessary is it on a diplomatic versus a tactical level?

For New Zealand, this was an unexpected step and probably a sign that it was under pressure to do more on Ukraine and provide something in the way of tangible support for the war effort. The very small amount suggests it is more symbolic than practical.

However, more significant was the decision to introduce autonomous sanctions on Russia – New Zealand had previously steadfastly avoided introducing a non-UN sanctions regime in order to avoid pressure from Western partners to use it. In the case of Russia, this is more symbolic than anything, given the minimal connections between New Zealand and Russia, but the precedent has now been set.

For smaller states in general, is symbolism what diplomacy is reduced to in the face of unconstrained violence by larger nations? You’ve been a vocal proponent of New Zealand’s potential role in helping negotiate a peace settlement in Ukraine. How feasible is such a proposal for a smaller state when confronted with asymmetrical geopolitical power dynamics and a violent, nuclear-armed antagonist?

The biggest problem is that it is impossible for New Zealand to really remain neutral in the face of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.

Israel has been involved in some mediation efforts so far and the fact that it has thus far refused to impose sanctions on Russia may make it a better candidate at first glance. Russia has already put New Zealand on the list of “unfriendly countries.”

On the other hand, there are problems with Israel as well as a mediator – it is a close US ally and an archenemy of Russia-backed Iran. China has also talked about being a mediator, but Xi Jinping’s close ties with Putin reduce the credibility of that option as well.

In the end, there are no perfect options. I don’t think you have much to lose by trying.

Diplomacy depends on trust. What happens to diplomacy when confronted with a negotiating partner who, for example, lied directly to multiple heads of state prior to an invasion, insisting that no such invasion was forthcoming? Does diplomacy not break down at that point?

The best time to stop the war would have been before it began, the next best time is now. The only real option is to look past what has happened in the past and be willing to negotiate in good faith. You have to accept the risk of disappointment. Emmanuel Macron must have known there was a real chance Putin was lying to his face before the war, but this potential embarrassment did not stop Macron from trying against hope to prevent the war.

Germany has just witnessed the collapse of its (very lucrative) economically-based foreign policy of Wandel durch Handel (change through trade) in regards to Russia. The country is now facing the reality of their dependence on Russian oil and gas. What are the difficulties in balancing diplomatic ties with trade?

The post-Cold War theory – globalization – was that trade would promote economic development and interdependence that would make war less likely. It is a good theory that makes sense; the problem is that politicians are not always economically rational actors. I am not sure what the alternative approach would have been in 1991. Should we have refused to buy Russian oil and gas to stop it from earning a living? Wouldn’t this refusal have just brought the tensions forward earlier?

Are trade concerns different for smaller states? New Zealand has long-standing geopolitical and trade ties with China. How will it balance diplomacy and trade if, as has been threatened, the West places sanctions on China for aiding Russia in the war?

The whole of the West is heavily dependent on China in different ways—for New Zealand it is export of raw materials, for the US it is more about offshore manufacturing and imports of finished goods.

This puts the West in a huge bind if China does enter the war. It has been relatively easy to isolate Russia and some states will even benefit from it. For example, the US will now benefit from selling far greater amounts of oil and gas to Germany. The same approach will not work for China.

In the Wall Street Journal earlier this month you pointed out that New Zealand’s historic lack of sanctions could lead to it being perceived as a haven for Russian officials who had evacuated their savings from other countries. What are the threats regarding international peer pressure or groupthink when it comes to diplomacy? How successful have countries been in walking the line between internal political culture and wider, global public opinion?

What has been particularly interesting with the Ukraine situation has been the enormous public pressure to show solidarity with Ukraine via sanctions. Many private companies have been pressured into withdrawing from Russia (McDonalds, IKEA, Coca Cola, etc.), even if they are not compelled to do so via government sanctions.

The New Zealand Government was initially reluctant to impose sanctions but soon came under huge pressure from all sides to do so—from Western partners, especially in the EU, from domestic political opponents, from the public.

The New Zealand Government clearly felt that it could no longer withstand the pressure and probably also realized that there would be significant economic costs if it did not impose sanctions – for instance, the EU probably would have held up a free trade agreement that New Zealand is currently negotiating with it.

The world is witnessing a nearly total isolation of Russia on the global stage, as well as a potential decoupling from China through sanctions (should they aid Russia’s invasion efforts). As a Russian speaker who has traveled extensively and studied Russian in Minsk, how badly, in your opinion, will future diplomacy be damaged by the isolationist fallout of this war?

This is the beginning of Cold War II, or the resumption of Cold War I, or however you like to see it. The fact that Europe is now quickly aiming for energy independence and is rearming means that there is no easy way back, even if a ceasefire is suddenly reached and Russia withdraws from Ukraine.

There are so many fundamental changes resulting from this – I think it is wider than just diplomacy. It is the end of the post-Cold War period and probably the return to a more ideological period with far greater suspicion and distrust between democracies and authoritarian regimes. It is a turning point and will change the way we see the world.

You have staunchly argued against political acts which cut off diplomatic ties, such as expelling ambassadors, maintaining they should be used as last resorts. You’ve insisted that it’s not even when diplomacy looks futile that we have to keep trying one last time, it’s especially when diplomacy looks futile that we have to try just one last time. We are now a month into this very bloody conflict. How do you think diplomacy can still influence the outcome of the war in Ukraine?

Turning the other cheek is important, however hard it may seem. The coordinated expulsion of every Russian diplomat in every Western country would be immediately satisfying to some, but would it make any difference to the war? I think it would be more likely to harden Putin’s resolve and change nothing. Has the severing of diplomatic ties between the US and Iran since 1980 helped either side?

Sanctions may have a similar result, although there is of course the faint hope that economic pain will change Putin’s mind. So far we are not seeing any sign of this, however, and countries under heavy sanctions such as Cuba and Iran have withstood enormous amounts of pain from sanctions without changing their positions.

Perhaps the comparison should be with sentencing common criminals – there is a punitive and a rehabilitative side to sentences. The Anglo-American approach of tough prison sentences, poor prison conditions has been shown to be less successful to the Norwegian approach that is more focused on rehabilitation. It is probably only human nature to focus on revenge, i.e. the punitive approach, but are we really better off in the long term?

Thank you again to Mr. Miller, and the Democracy Project, for granting this interview.

Read More:

- Why the world must stop Putin in Ukraine

- Martyred city of Mariupol wiped out of existence by Russia’s incessant shelling

- How the Lviv train station welcomes Ukrainian refugees fleeing Russia’s war | Photo report

- What weapons for Ukraine would help it win the war against Russia

- Putin likely to view West’s declarations about Ukraine as appeasement, as Hitler did their predecessors’ words about the Rhineland, Pastukhov says

- Garry Kasparov: If Putin’s nuclear blackmail works against Ukraine, he will use it next in Poland or Estonia