Today, Russia is using similar tactics -- provocation, lies, disinformation -- in its war with Ukraine, but this time, Ukraine has a good chance of winning.

This article is part of the #PatronVote series. Our patrons can vote for the topics we cover next. Become one of them for as little as the cost of a cup of coffee per month here.

The situation in and around Ukraine is increasingly reminiscent of the Sudetenland Crisis in 1938 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962.

What is at stake? In a word, the lives of thousands of people; regional peace and security, and what is left of trust and common sense in Eastern Europe. Many Ukrainians are convinced that their very existence as a nation and state has been put on the line.

Russian President Putin has demonstrated that he wants to play a bloody game if the United States and NATO do not meet his demands immediately.

Russia has surrounded Ukraine with troops and military hardware - from Brest in Belarus to Tiraspol in Moldova’s separatist Transnistria region. Permanent military exercises are underway on land and at sea near Ukraine's borders.

If you ask Ukrainians whether a war will break out, many of them will look at you reproachfully and say that the war began many years ago, in 2014.

The logical and correct questions that we should be asking ourselves are as follows:

- Will there be an escalation?

- Will Russia launch a major offensive with armored spearhead attacks, aerial bombings, and missile strikes?

These questions have been hanging in the air in many world capitals, especially in Kyiv.

Experts and journalists are actively discussing different scenarios of the Great War. The Washington Post and Bild published menacing maps of possible attacks. Ukrainians are used to this.

In 2015, Stratfor analysts published similar maps with arrows pointing deep into Ukrainian territory.

The assumption about the inevitability of Ukraine’s defeat stems from the huge disparity between the military capabilities of the two countries. The Russian army is larger, better equipped, armed with a wide arsenal of lethal weapons, and possibly better trained.

However, there is room for many surprises.

In fact, we are talking about a possible direct collision between the largest country in the world and the largest country in Europe. A powerful army with combat experience in Chechnya, Georgia, Syria, Crimea, and Donbas will encounter a smaller but highly motivated army that has risen from the ashes.

In principle, many people do not understand how two countries, which are so similar in language, religion, culture and have coexisted for centuries, can go to war against each other. But, Russia’s carefully cultivated myth of brotherhood, of ethnic unity between Russians and Ukrainians throws a spanner in the works.

In order to imagine how Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine could unfold, we should look at historical precedents.

Yes, the two Slavic neighbors have been at war before, and by historical standards, quite recently… just one hundred years ago.

Of course, it would be wrong to make direct comparisons between wars that took place at different technological periods. At that time, attacks were launched with the participation of, for example, the cavalry and armored trains.

And yet, these conflicts occurred in the same geography, with almost the same participants and similar methods of aggression, which we now call “hybrid.”

The historical predecessor of modern Ukraine, the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was proclaimed in November 1917 on the ruins of the Russian Empire, which crumbled after World War I and the Revolution.

The UNR existed about four years before the UNR army laid down its arms and its territory was divided among neighboring states. However, we should consider two military campaigns, which were launched during this short but eventful period. In some ways, they can be compared to Russia’s imminent attack today, with some caveats, of course.

The two Soviet invasions of the UNR: in 1917 and 1918

Vladimir Lenin’s Russia opposed the UNR. The conflict had both interstate (Russian-Ukrainian) and social features (expansion of the Bolshevik system).

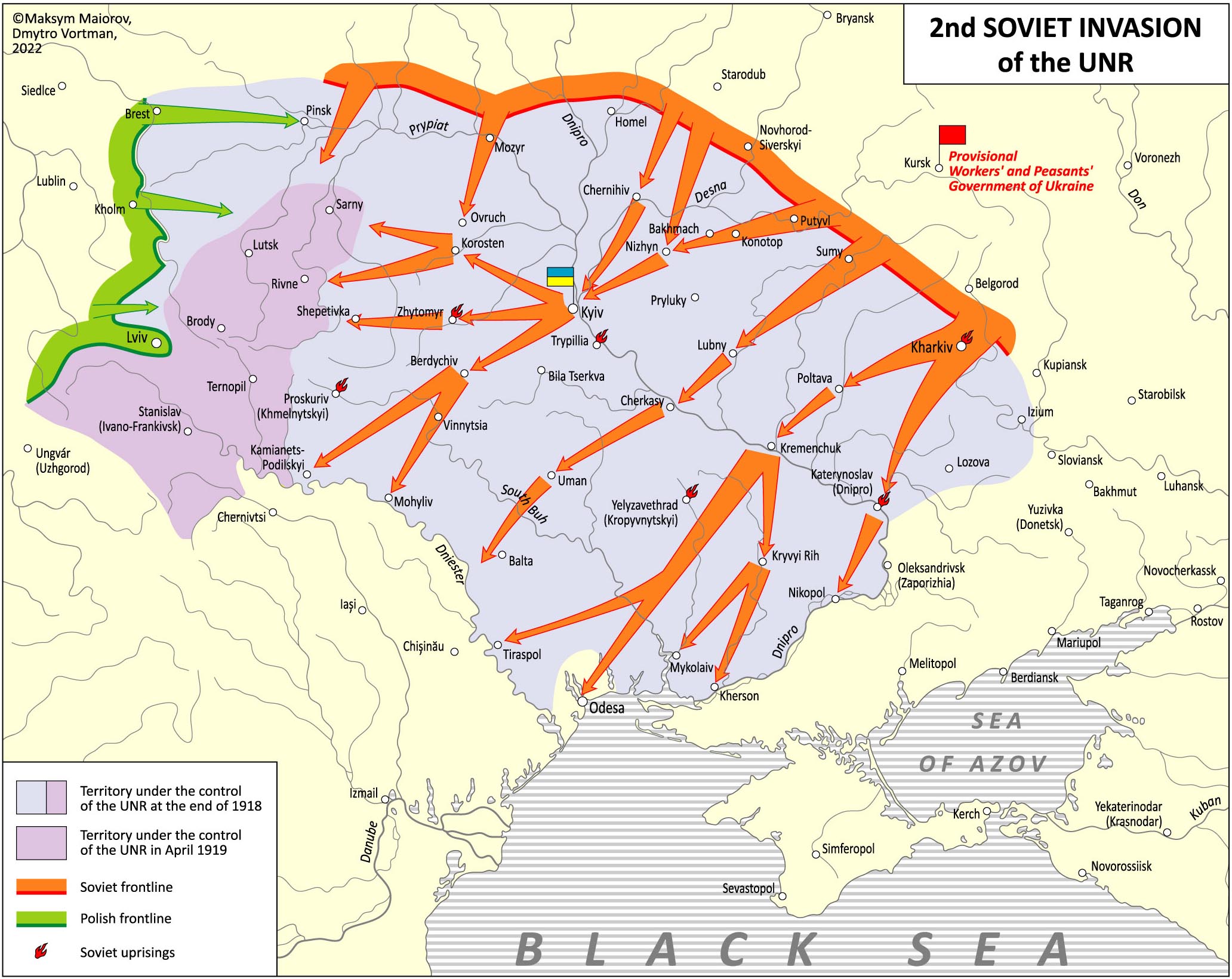

The invasion of Ukraine began in December 1917. Russian troops took control of Kharkiv, Katerynoslav (now Dnipro), Poltava, and Oleksandrivsk (now Zaporizhzhia). They advanced through Chernihiv region and reached Kyiv, which they occupied relatively easily. Further battles with the Ukrainian forces continued on the right bank of the Dnipro River.

In the end, the Bolsheviks were forced to withdraw from Ukraine, but about a year later they invaded again.

During the first and second wars against the UNR army, there was a great difference in the nature and scale of combat operations. However, the arrows on the map are similar in both cases. They were determined by the geography of roads and natural obstacles (especially large rivers). Little has changed since then, so this should be taken into account when we talk about today’s war.

Moscow dismisses all responsibility, declaring that Ukraine is in the midst of an internal, civil conflict. Putin originally stated that “local self-defense units” had seized military bases in Crimea. In the Donbas, the Kremlin continues to point to the presence of “local militants.”

It was the same in the past.

During Russia’s two invasions of the Ukrainian National Republic in 1917 and 1918, the Bolsheviks formed Ukrainian puppet governments on whose behalf they fought the UNR army.

In December 1917, it was the People’s Secretariat in Kharkiv, and in November 1918, the Provisional Workers’ and Peasants’ Government of Ukraine in Kursk.

In 2014, Putin was unable or unwilling to create an alternative “all-Ukrainian government” even though he controlled both the fugitive ex-President Viktor Yanukovych and his supporters in different Ukrainian regions. Today, Moscow has chosen a different path: supporting separatist groups in Ukraine’s border regions. We all know how the Donetsk and Luhansk “people’s republics” were created. In other regions, other “people’s republics” were either stillborn or slipped quickly into oblivion.

The forerunners of regional separatism

The forerunners of regional separatism appeared during the first Bolshevik aggression against the UNR.

In early 1918, the Donetsk-Kryvyi Rih Soviet Republic, the Odesa Soviet Republic, and the Taurida Soviet Socialist Republic were proclaimed. Modern ideologues of pro-Russian separatism appeal to the history of those entities as their heritage.

However, in the case of a large-scale invasion, this approach may change. In January this year, the United Kingdom uncovered Putin’s secret plans to overthrow the government in Kyiv

and replace it with an administration presided by Yevheniy Murayev, one of Ukraine’s most notorious pro-Russian politicians.

Illusion of a friendly empire: Russia, the West, and Ukraine’s independence a century ago

One hundred years ago, Ukraine was in a much worse strategic situation than it is today. The republic was very young, and it was in the throes of growing pains. Regional administrations were weak, the army undisciplined, and large cities were populated by mostly disloyal to the UNR people. The authorities made crucial mistakes, and the aggressor used them to spread powerful and masterful propaganda.

Today, Ukraine and the West are conscious of Russia’s threats and propaganda.

The lack of international support for the UNR

Matters were no better for the UNR on the international arena. During the first Bolshevik aggression, the front line of World War I was still present in the western regions of Ukraine. There were no battles, but demoralized and angry soldiers from the former Russian Empire emerged from the trenches and destabilized the Ukrainian rear. A year later, during Russia’s second invasion, Ukraine had to fight against Poland in the same regions.

The democratic countries, united by the Entente, were skeptical, suspicious, and often hostile to the UNR.

Despite the fact that The UNR found itself in such unfavorable circumstances, the Russian invasions were not able to subdue the Ukrainian army all in one go.

As mentioned earlier, after the loss of their capital, UNR troops retreated to the right bank of the Dnipro River. There, on the last controlled territory, they managed to gather the will and strength for a counteroffensive to return to Kyiv. This happened in March 1918, and then again in August 1919.

The Ukrainians reorganized their army, found allies, and took advantage of a more favorable international situation. They fought until they had no more strength left to resist.

Modern Ukraine feels much more confident than the UNR.

It has been independent for 30 years; the Armed Forces of Ukraine have been building up their strength and skills for eight years; Ukrainian soldiers are battle-hardened with years of experience on the contact line. Ukrainian society is more consolidated than ever before.

Kyiv, which was the Achilles’ heel of the first republic (it rebelled against the government), has become a stronghold of democratic Ukraine, as evidenced by the Revolution of Dignity in 2014.

Ukraine is no longer isolated but enjoys the sympathy and full support of the West. Leaders and diplomats of leading countries stand up for Ukraine and declare their support both loudly and publicly. Western governments issue positive decisions in favor of Kyiv. They supply weapons and other material needed to fight and repel the aggressor.

In contrast to 100 years ago, Ukrainians no longer trust the flow of hostile propaganda and disinformation. Together with international partners, they develop effective strategies to combat lies and hybrid threats.

So, with this in mind, doesn’t it seem that Ukraine has a good chance of winning today?

Maksym Maiorov is an analyst at the Centre for Strategic Communication and Information Security. He worked at the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance during 2014-2021.

Related:

- UK warns of Russian plan for coup in Ukraine. Here is what we know about its potential leader

- Of Kremlin plans and thinking. The “Murayev coup” plot seen through the prism of the Surkov Leaks

- How do the military forces of Ukraine and Russia compare?

- Ukraine’s Territorial Defense volunteers prepare to support army in case of Russian invasion

- How Communist propaganda made eastern Ukraine hate the national liberation movement

- Unique 1919-1920 map of Ukraine exhibited in Prague

- The Kremlin’s playbook: fabricating pretext to invade Ukraine – more myths

- The Ukrainian Revolution of 1917 and why it matters for historians of the Russian revolution(s)

- Illusion of a friendly empire: Russia, the West, and Ukraine’s independence a century ago

- Euromaidan, rebirth of the Ukrainian nation, and the German debate on Ukraine’s national identity

- Russia’s occupation of Ukraine: a historical and centuries-old process

- Documentary rediscovers iconic designer of 1917 Ukrainian state symbols. Watch it here

- The History of the Ukrainian National Flag (Infographics)

- One century ago, rebellious Khabarovsk dreamt of becoming a Ukrainian colony

- Ukraine today a continuation of Ukrainian Republic of 1918-1920, Verkhovna Rada speaker says

- How the UNR Army liberated the Donbas in 1918

- Vasyl Vyshyvany: the Habsburg prince who chose Ukraine