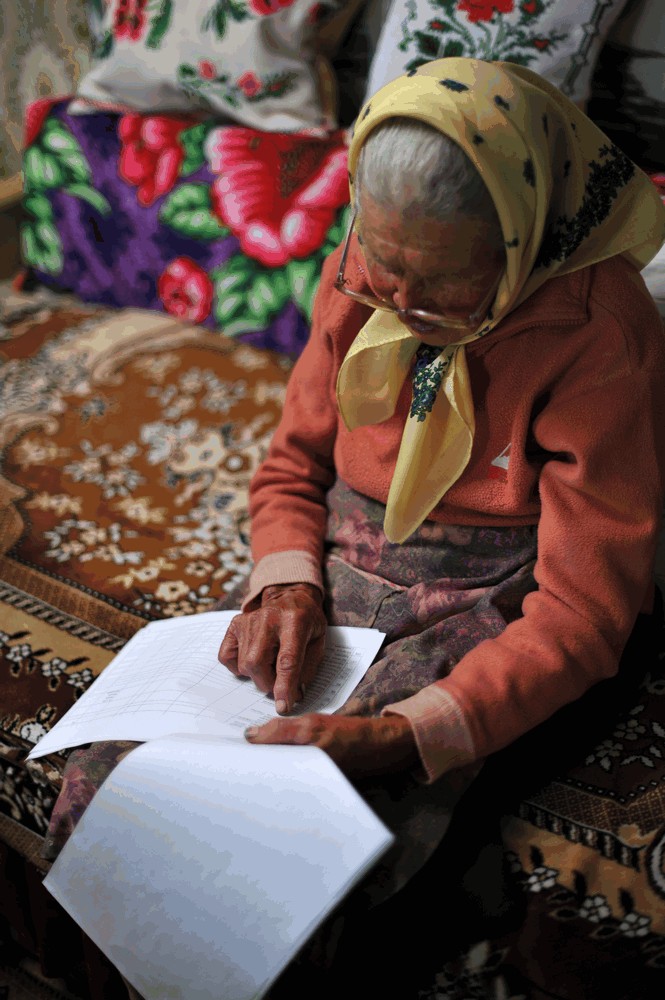

Vasylyna Antonivna Yarovenko was born on 5 April 1923. “On Thursday,” she adds laughing. Her daughter explains, “It was the feast of Holy Thursday.”

Vasylyna's mother Teklia Frantsivna originated from the family of the Polish state peasants, brought to the Kuriantsi village (now Vinnytsia Oblast) by landowner Jabłoński. The grandfather of Vasylyna, Franko Trotskyi, was an initiator of the collective lawsuit against the landowner, which resulted in transferring the land to villagers. This was the way how the Trotskyi family received a plot of land and established their own household. At the same time, landowner Jabłoński soon took to drinking and grew poorer. People used to say then, “Our village has a landowner who borrowed the money from my grandmother.”

Vasylyna Yarovenko’s father Anton was the son of wealthy farmer Ladymyr Kashchuk, who had shared his property among his seven children in 1917. Anton inherited 5 hectares of the land, and he was a middle-class peasant by the standards of the mid-1920s. The family had horses, sheep, pigs, and a cow, and the older son of the Kashchuks had a dovecote.

At the end of 1926, the house and household were destroyed by the fire, and the Kashchuks had to start everything over again. They rebuilt their house and the storehouse, covered them with roofin iron, gradually restored other buildings, and even got into bee-keeping. Vasylyna's father began constructing a new house for his older son.

Those bad at managing their farms were first to join the collective farm

When the collectivization propaganda came to the village of Kuriantsi, the first people to support it were the ones who were terrible at keeping their own households. Many of them were envious of more successful and wealthier farmers, including Vasylyna’s father. Some people used to say in the village, “Kashchuk eats varenyky, and I will eat varenyky.” They didn’t realize that behind “Kashchuk’s varenyky” was the hard everyday toil.

“The administration's members were only poor people not adapted to life. I knew such people who had families, and once they had heard 'kolkhoz' and even 'commune,' they were like 'woo-hoo! a commune! here will be a commune!' They themselves were clueless! They had some three or five hungry children at home and some neglected field,” Ms. Yarovenko says.

Anyway, the communist propaganda didn't succeed a great deal in the village due to the fact that the people who were running the campaign were far removed from the real-life and actual needs of the people.

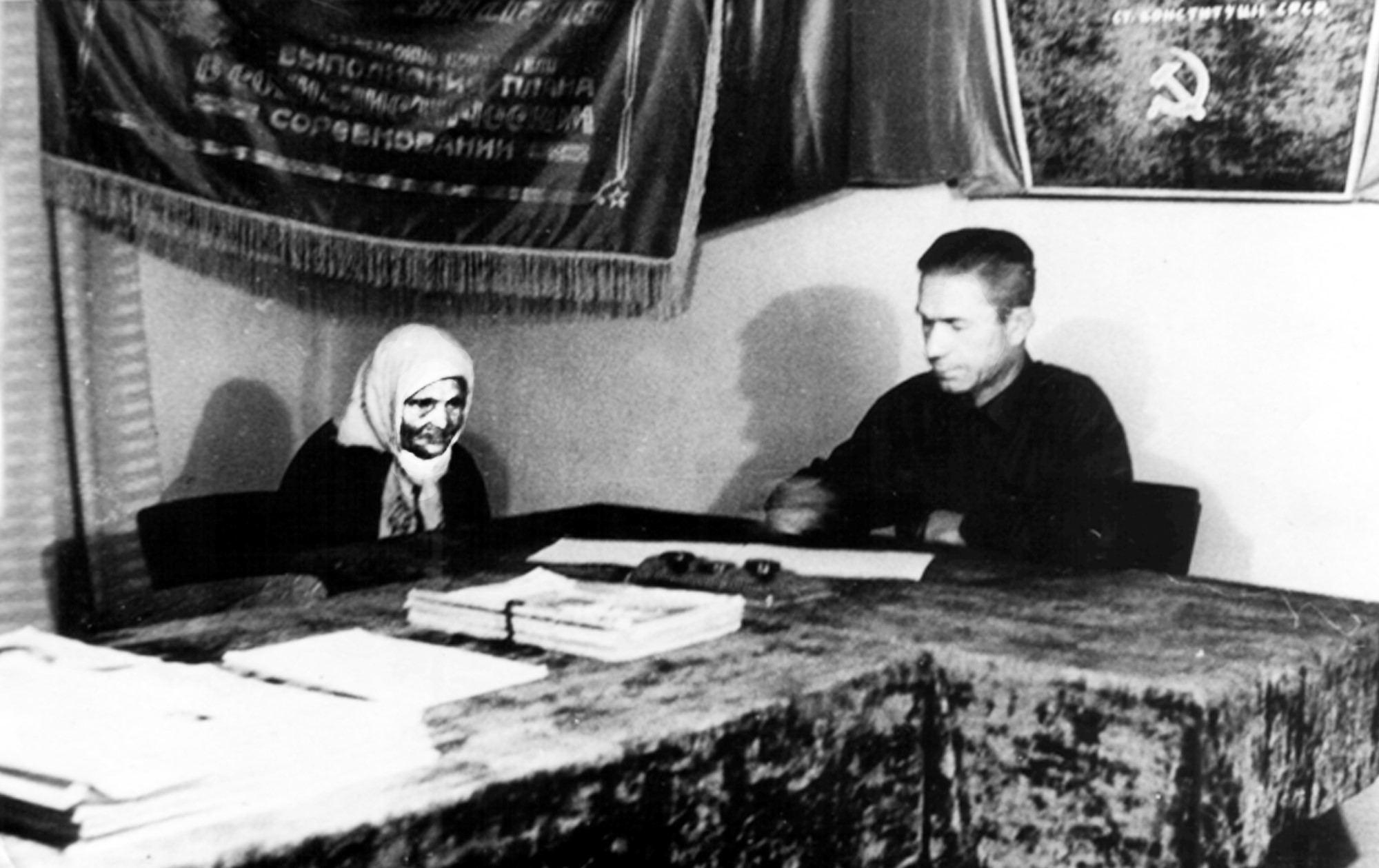

Vasylyna’s father Anton Kashchuk as one of the most successful farmers was initially put on the kolkhoz activist list, but he refused to join them as he didn’t want to force fellow villagers to give away their property to the kolkhoz. Later, he was still forced to become a member of the collective farm and worked as a courier delivering products to a local shop.

Communists confiscated the village priest's property and threw him out on the street

Vasylyna’s grandfather Ladymyr Kashchuk was first a teacher in a church-parish school. By the late 1920s, he had become a churchwarden. He was on friendly terms with the local priest, Yevhenii Matsievych. With the escalation of the Bolshevik anti-church campaign, the priest apprehendingly asked Ladymyr Kashchuk to buy all of his furniture. And he asked Ladymyr to use the money for buying a small house for the priest so that he'd “be able to live there until his death.” This is how the father of Vasylyna Yarovenko furnished his home with the priest’s home items,

“My father bought a floor-to-ceiling mirror, a big clock with a pendulum -- it hissed, two cabinets, one for clothing and the other for books, kitchenware, and a table. The table was round with three legs, such carved and massive. A locker with three drawers, a small sofa -- how would you call it? -- a couch, it's now called a couch but back then we called it a 'kanapa.' It was upholstered with some kind of carpet. All in all, there was a really beautiful atmosphere,” Vasylyna says.

My neighbors escaped starvation by eating grain stored by field mice | Voices of Holodomor witnesses

Priest Matsievych was offered to abdicate his priesthood willingly and get employed as a kolkhoz accountant. Such a strange proposal came thanks to the fact that at the time there was a lack of literate people. Nevertheless, the priest rejected such an offer,

“I will not give up my cross, I won’t go to work as an accountant in the village. I could have done it somewhere else, but here the children would laugh of me,” Vasylyna Yarovenko recalls his words.

Soon, the authorities confiscated the priest's property and evicted him from his own home. Later they repurposed his house as a school and disassembled for firewood the small house that Ladymyr Kashchuk had bought for him. Priest Yevhen Matsievych died very soon after.

Authorities could seize anyone's property and deport them

The end of the 1920s saw the beginning of the so-called dekulakization or liquidation of "kulaks" -- the wealthy peasants or "hosts" in Vasylyna Yarovenko's words. The authorities could label anyone and everyone a "kulak," not only the wealthy villagers. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the communists deported more than a million Ukrainians to the distant regions of the USSR. Those were labeled "special resettlers."

Life in the "exile settlements for the kulaks" was so hard that few people could bear it. Many forced exile settlers died as early as on their way to the northern regions of Russia in railway cattle cars.

Amid the dekulakization, the Soviet authorities exiled several people from the village of Kuriantsi. One of those was Hryhir Muzychuk, who was an old man at that time, had a steam thresher that he used to lend to his fellow villagers. They deported him with his wife Khivrona and his toddler child to Siberia. Just after their arrival, the man died. His wife decided to get back home on foot. With an infant in her arms, she walked to Ukraine from the Siberian taiga, collecting dews for drinking and asking people for food on her way home. When Khivrona finally reached her village, she couldn’t get her house back, because the authorities were using it as the so-called club or the house of culture, which forced her to settle in an empty nearby house.

Another claimed kulak wasn't wealthy at all. Together with his two daughters, he was also deported from the village. His third daughter managed to go on hiding, and then, now married to Vasylyna's brother Prokop, she moved to live with the Kashchuks.

Communist activists confiscated all food from the Kashchuks, arrested Vasylyna's brother

In 1932, the family of Kashchuk, of which its five members were kolkhoz workers at the time, received their grain for the so-called trudodens from the rich harvest,

“We earned so much grain; our storehouse was full. That is how rich the harvest was in 1932,” Vasylyna Yarovenko recalls.

Yet in the winter of the same year, right before Christmas, a communist activist came to the family's house to take away the grain they had earned and to arrest Prokop Kashchuk, Vasylyna’s brother. The authorities charged him with theft of grain from the kolkhoz storage, even reproached him for being married to the "kulak's daughter," and convicted him to three years in jail with confiscation of property.

“Two sleighs arrived full of these activists… A lot of them in the entryway, storage -- they were grabbing it all. There were such granaries, weaved straw baskets. They took away grain, and everything. They left nothing in the house, took everything. They took away riadno from the stove coach, no riadno left to cover it. They took away everything. If we had at least some handmade textile we'd sow it, but there was nothing,” this is how then nine-year-old Vasylyna remembered the communist expropriation.

The authorities took away from the Kashchuk family not only their food but also the furniture they had bought from the priest and many household items -- benches, pillows, clothes, etc. Soon, these things popped up at special auctions or fairs, but not all of them -- the activists held back the best articles for themselves. The large mirror emerged in one of the offices of the district authorities. When they started to build a kolkhoz storehouse, the activists took away the plates from the Kashchuks' house roof and took apart their storage.

When the activists searched the house, Anton Kashchuk, Vasylyna’s father, realized that he could be also arrested, so he decided to escape in order to save his life. He took a loaf of bread under his arm and asked his daughter to secretly open the window in the next room, "I'll go out of the window, but don’t tell anyone. If you do, then they'll take me away, judge, maybe, execute me.” Frightened, she silently did what he asked. Nobody in the family knew where he was hiding.

Vasylyna worked in kolkhoz fields to survive

As it turned out later, Vasylyna's father reached as far as Russia's city of Rybinsk, north of Moscow on the Volga river. He managed to get a job there and soon decided to move his family to his new place. However, it had to be done in secret, in order to avoid the risks of being arrested.

Anton Kashchuk got in touch with his nephew and asked him to help in bringing his family to Rybinsk. The nephew took Anton's wife Teklia and two of their younger daughters, but the woman asked him to let the older daughter, Vasylyna, stay in Kuriantsi as someone who would care for the children of Teklia's son and daughter-in-law. On the same day, the girl woke up alone in the empty house, her mother and sisters were gone.

In Rybinsk, according to Ms. Vasylyna’s father, there was no famine at all. The father worked as an unskilled laborer at a glass factory and her mother as a janitor. Later, when the famine in Ukraine declined, the family came back home to Kuriantsi.

During the Holodomor, ten-year-old Vasylyna Yarovenko was doing her best to find ways of surviving. In particular, in the spring, she started working in the kolkhoz and, weeded beetroot there. She worked as much as adult women but received only half their "payment" -- a half-pound of bread or some 200 grams.

“They go to the beetroot field, weed it, each takes two rows to weed. These were 'runs,' two rows were the 'runs.' And one row was called a half-run. The one who goes through the two rows received a pound of bread. The pound of bread is 400 grams. And for those with one row were given a half-pound. And I was given a half-pound, and they a pound each.”

Moreover, the kolkhoz organized a collective meal for its workers. However, Vasylyna Yarovenko recollects that she could not even get close to the pots where the food was cooked. In despair from hunger, people tried to snatch at least some of food, and their behavior was rather beastly than humane.

“They were cooking some kind of halushki there or something, I didn't risk to get there, as the crowd could choke you there. The water was boiling, bubbling greatly with women feeding the fire under the pots, and screaming people with their soup bowls thrust their way there. They were like a herd of sheep - someone does something to them they bleating. These screamed so much, it was so terrible!” Vasylyna recalls.

At least 209 villagers died of hunger

All members of Vasylyna Yarovenko's family survived the Holodomor, yet the deaths of starvation of her fellow villagers imprinted on her memory forever.

Her neighbor Oleksandra Hubar buried her three adult children, Mykola, Petro, and Pavlo. Only her youngest son Ivan lived on, who was eight at that time. She asked her acquaintance, Yuhyna Voitsekhivska, to help her in burying her sons. Nobody made coffins then, so the women used to lay their children's bodies on a ladder, wrap them, and they would dig up and fill up the pits with their own hands.

When the mortality rate reached its peak, a cart shuttled across the village and gathered the bodies of the dead to bring them to the cemetery, where they had a prepared “kahat” where they were laying the corpses together. In time, an iron cross was raised there.

“We had a wide long street on the edge of our village, and a lot of children used to live there. And those children -- just like that -- were dying one by one, one by one,” Vasylyna Yarovenko remembers.

The woman remembers the names of many fellow villagers killed by the famine of 1932-1933. The list of names of the Holodomor victims, compiled by the local village council in modern times based on the testimonies of such witnesses includes 209 victims. However, the actual death toll may be higher.

Another fact that proves mass mortality in Kyriantsi is that the Holodomor left behind a lot of orphaned children. To take care of them, the kolkhoz direction set up a patronage facility, where the children were raised until their coming of age.

Breakfast from cooked fodder beetroots was only reason for children to attend school

In 1933, Vasylyna Yarovenko was a school student. She didn't have winter clothes as earlier the communist activists confiscated them together with food and furniture. A fellow villager who had bought her winter coat at the sale fair for eight Soviet rubles offered her to work it out by tending his cow for a month. Vasylyna agreed and this was what gave her the possibility to continue attending classes.

It wasn't their thirst for knowledge that kept Vasylyna and other schoolers in school, but the “hot breakfasts” cooked from fodder beet.

“The washed grated fodder beet with water - this way they used to boil it. Some noodle-shaped things. They salted it and gave it to you. At least you get something hot, especially when you had nothing…” Ms. Yarovenko recalls.

"I grazed the cow, and grazed myself with her," Vasylyna said

The people who knew her discouraged her from going to school in winter as she could have died from exhaustion or hypothermia on her way there. Yet the girl knew that the “hot breakfasts,” even that unpalatable and not that nutritious, were her only way to save herself from a hungry death. But not all of the school children were hungry. The children of activists didn’t need “the meal” at school.

“If there were those hot breakfasts, it was seen. Who would eat it if they ate well at home? Why would they need to go there? There came the ones who were hungry. I always went there; I ran fast there. I could eat something hot.”

My village once saw twelve people die of hunger in one day | Voices of Holodomor witnesses

In addition to the fodder beet "noodles," Vasylyna Yarovenko consumed other food surrogates. Tending the cow to get her coat back, she used to eat edible herbs -- wild leek, wild garlic, and cummin alike. Also, she had to eat the corn cobs -- these needed a lot of cooking to become suitable for consumption,

“So, I used to peel the corn cobs, and there was the pith inside. I'd cut it into wee small pieces, put it on the stove, and cook. But it was cooking reluctantly. It was like rubber. When it was ready, I salted it, and drank it this way,” Vasylyna says.

From time to time, Vasylyna was going fishing with her cousin. His family used to give the girl some food for her help in fishing. Vasylyna also collected ears of grain on a fallow field. She had to do it stealthily so that "people wouldn't know or see it" because it was a criminal act under the Soviet laws of the time. The found grain crushed with the poppy pestle was used for baking the pampushky.

Her neighbor, Oleksandra Hubar, also used to gather grains on the kolkhoz field for her youngest son, the only one who remained alive out of her four children,

“She would gather some rye or wheat, some ears of grain, and bring that home in her fist or in some small pocket because you couldn't openly carry it in some bundle,” Vasylyna recalls.

The woman used to bake the grains in the oven a little bit and scatter them on the floor to give her hungry toddler something to do. These seeds saved her boy’s life.

In time, Vasylyna Yarovenko’s parents returned from Russia and found jobs in the nearby village of Novofastiv -- they were employed by a sovkhoz there -- a state-owned farm, basically the same kolkhoz with a formally different form of ownership. They gradually restored their household destroyed by the communist totalitarian regime.

Empty houses in the Kuriantsi village were reminders of the Holodomor for a long time. Now, those events live on in the memory of the witnesses, who tell the stories of the families to their descendants.

Further reading:

- Every day two or three people died in our village | Voices of Holodomor witnesses

- My village once saw twelve people die of hunger in one day | Voices of Holodomor witnesses

- My family survived Holodomor by eating waste left from sugar production | Voices of witnesses

- An Austrian engineer showed these Holodomor photos to Cardinal Innitzer in 1933, pleading for aid to the starving

- Surviving in the “collective farm paradise”: voices of living Holodomor witnesses

- How my father saved his co-villagers from starvation during the Holodomor

- My neighbors escaped starvation by eating grain stored by field mice | Voices of Holodomor witnesses

- “Let me take the wife too, when I reach the cemetery she will be dead.” Stories of Holodomor survivors

- Stalin’s management of Red Army proves Holodomor a Soviet genocide against Ukrainians

- Bread from tree bark and straw: students launch online “restaurant” with Holodomor “recipes”

- Holodomor in Kharkiv through the lens of Austrian engineer: photo gallery

- Holodomor: Stalin’s punishment for 5,000 peasant revolts

- Engineer Wienerberger’s unknown photographs of the Holodomor