"Behemoth"

On 7 September, the Prague City Court sentenced in absentia to 20 years of prison time Czech national Jiří Urbánek (call sign Behemoth) for being a member of a terrorist group and committing a terrorist attack.

.

According to the investigation findings, Urbánek went to Ukraine in 2015 to join the militants and participated in their operations at least until January 2018, helping them in digging trenches, taking part in patrolling, and participating in hostilities against the Ukrainian army near the Donetsk suburbs of Mariinka, Krasnohorivka, and Spartak.

Urbánek was tried in absentia and didn't keep in touch with his lawyer.

On September 7, the prosecutor in his closing argument proposed that Urbánek be sentenced to 20 years in prison. The lawyer asked for an acquittal or a milder sentence, expressing doubts about the legal qualification of the defendant's acts and that his client's Facebook profile provides clear evidence of Urbánek's involvement in the hostilities. The court supported with the arguments of the prosecution.

It is noted that another Czech, Pavel Botka, fought alongside him. In 2019, the latter lost his leg after tripping an explosive device.

Urbánek's mother and brother refused to testify in court, though their testimony in the case confirmed that he was in Ukraine.

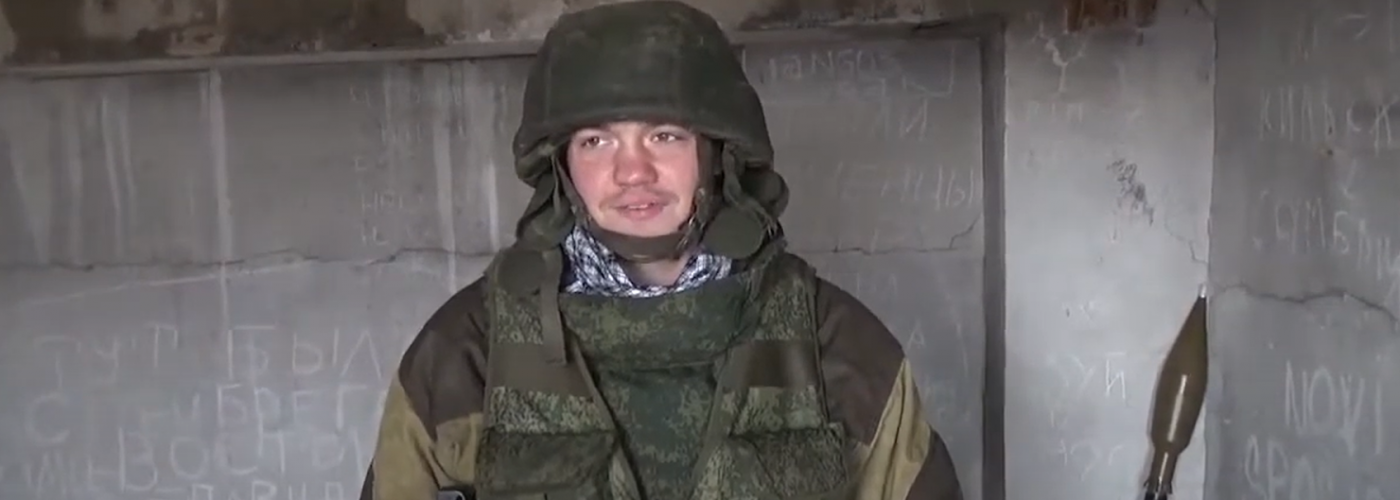

Nováček

On 8 September, the District Court in the Czech city of Plzeň sentenced 27-year-old Lukáš Nováček to 20 years in a high-security prison for taking part in fighting in 2015 in eastern Ukraine alongside Russian forces against Ukraine.

According to the case files, Nováček went to the Donbas in July 2015, where he took an active part in the activities of militants of the so-called "Donetsk People's Republic."

Nováček was convicted of a terrorist attack and participation in an organized criminal group. The verdict is not final, and the accused filed an appeal on the spot, constantly claiming that he didn't take part in hostilities.

Nováček himself told several other people who testified in court that he had partaken in the fighting in Ukraine. According to the court, the witnesses didn't know each other. Nováček later said that he was just bragging.

A medical report states that the reason the man had a psychiatrist's consultations was that he had fought in Ukraine and was suffering from mental health problems.

Pieces of evidence of his guilt also include photos and videos taken on his cell phone, in which he poses with firearms wearing the uniform of militants. In one of the videos shot near the Donetsk airport, he speaks out why he's there in broken Russian. He claims that he wanted to fight the Ukrainian "fascists" and says that he's ashamed to see what Ukrainians are doing to the civilian population.

Nováček stated in court that he didn't take part in hostilities, but only worked in the kitchen.

"I went there to see a girl named Natasha, whom I met on a social network. I was persuaded to join the army of Novorossia. I didn't want to die there, so we agreed that I would just be a civil servant, assisting in the kitchen, etc. I handed over my passport upon arrival," he claimed.

- Read also: How Czechia became a leader in convicting ex-mercenaries who fought against Ukraine in the Donbas

It is worth noting that this April, the Czech Republic detained five other persons suspected of participation in hostilities in the Donbas on the side of pro-Russian fighters. Within days, the Prague District Court ordered the arrest of three suspects.

In June, a Prague City Court sentenced Czech citizen Martin Cantor, who fought on the side of the so-called Luhansk People's Republic, to 20 years in prison.

Read also:

- Czechia detains Crimea annexation participant at Ukraine’s request

- How Czechia became a leader in convicting ex-mercenaries who fought against Ukraine in the Donbas

- How Russia recruits Serbian mercenaries into the ranks of its fighters in Donbas

- Reputed Czech furniture company doing business in Russian-occupied Donetsk

- Czech Constitutional Court rules in favor of hotel ban on Russian citizens approving Crimean landgrab

- From English into Russian into Czech: re-translation as a Russian propaganda’s manipulation tool