Mercenaries from more than 30 countries took part in Russia’s war against Ukraine in the Donbas, but only a few countries are working systematically to identify and prosecute their citizens, according to the Ukrainian prosecutor’s office. So far, the Czech Republic has convicted most of its citizens who had taken part in the war against Ukraine on the side of Russian hybrid forces.

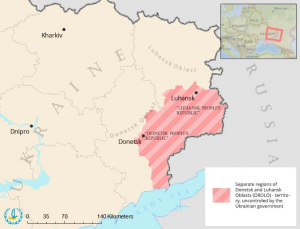

As of the end of June, according to the Ukrainian embassy, Czech courts had served six sentences on charges of terrorism to Czech citizens who had fought on Russia’s side among the fighters groups of the so-called LDNR (Russian-run Luhansk and Donetsk “people republics” – DNR and LNR, – Ed.). A number of other cases have been currently under investigation by Czech law enforcement with verdicts expected soon.

The participants of the webinar, which was held on 29 June jointly by the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union (UHHRU) and the Media Initiative for Human Rights, discussed why these cases have become important for the Czech Republic.

Back in 2016, the Czech city of Ostrava saw the opening of the so-called “DNR consulate,” Czech President Miloš Zeman voiced statements that the loss of the Crimea to Ukraine was a fait accompli and Kyiv would better bargain a discount for buying fossil fuels from Russia, while some right-wing Czech parliamentarians paid visits to the occupied Crimea and Donbas.

However, according to Ukrainian Ambassador Yevhen Perebyinis, the Czech Republic is a state governed by the rule of law, where law enforcement agencies operate regardless of the political context. Therefore, the Czech state institutions didn’t pay attention to propaganda and worked systematically, and throughout 2016-17, the so-called “DNR consulate” was shut down by a court decision.

According to the Ukrainian ambassador, the work of the Czech law enforcement and judicial authorities could be an example for other countries, where the Russian hybrid spy network similarly tried to present the Russian invasion and occupation as a “civil war in Ukraine” (the civil war narrative is concurrent in the Russian propaganda since 2014, – Ed.). According to Yevhen Perebyinis, even the court hearings and the wording that were heard in court were important to call a spade a spade.

According to Roman Máca, a Czech security expert who has been monitoring the activities of Czech pro-Russian forces for years, in addition to Pavel Kafka, for now, the verdicts have also been delivered against Erik Eštu, Oldřich Grund, Martin Kantor, Lukáš Nováček, and Aleksey Fadeev, a Belarusian citizen. For some of them, cases and court hearings took place in absent, since some are hiding in Russia, some in the occupied territories in the east of Ukraine, as for others, it is unknown whether they are still alive.

“The first was the Belarusian citizen (he had a residence permit in the Czech Republic – Ed.), And the second one was a Czech named Pavel Kafka, who was sentenced by a court firstly to probation, and then, appealed, to a “real” sentence – the three-year imprisonment for his participation in hostilities,” the Ambassador stressed.

According to Roman Máca, the motivations of people who went to war against Ukraine varied. Some were attracted by the ideology – they wanted the restoration of the Soviet Union and believed that they could return it in this way, others fled from justice in the Czech Republic, incurring debts, others could not find their place in life and sought adventure. Such was the case of Pavel Kafka, a young man without a family who grew up in a foster family and dreamed of a career as a “brave soldier.”

The Ukrainian ambassador said that lately, his embassy received a letter from Pavel Kafka from the penal colony, in which he continued claiming that he had not taken part in hostilities despite this being proven in court, but also said he’d like to apologize to Ukraine and even believed “that for Ukraine it will be possible to restore its territorial integrity using diplomatic means.”

According to the ambassador, the wording and legal qualification of the actions of Czech militants provided by the Czech prosecutor’s office and courts are very important.

“As a rule, almost in all cases, the Czech prosecutor’s office indicted them with ‘participation in the commission of a terrorist act.’ Not all courts agree with this wording – the court sometimes changes it to the ‘participation in an organized criminal group,’ because Russian troops in the Donbas and their proxies are, of course, a criminal group, and it’s organized. In any case, it is important that the Czech courts follow this path and a number of court decisions is to come in the near future,” the ambassador said, adding that the Czech prosecutor’s office is actively cooperating with Ukraine and plans to expand this cooperation in order to replenish the evidence base.

Yevhen Perebyinis pointed that in the case of the Belarusian citizen, the Czech judiciary used the norm of universal jurisdiction (a type of extraterritorial criminal jurisdiction that allows states or international organizations to demand criminal proceedings against an accused person, regardless of their nationality, country of residence, and regardless of where the alleged crime was committed, – Ed.), terrorism and illegal armed groups exist in the context of Russia’s war against Ukraine and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is helping Czech courts determine the international legal status of these events.

The example of the Czech Republic, according to Perebyinis, is important for law enforcement agencies of other countries, which, responding to Russia’s subversive activities in their countries, protect themselves, in the first place, but also support Ukraine.

According to Olha Reshetylova of the Media Initiative for Human Rights, Ukrainian courts are not as consistent in classifying the crimes committed by militants in Donbas:

“These cases are qualified very chaotically under various articles of the Criminal Code: encroachment on the territorial integrity of the state, high treason, creation of a terrorist organization; preparing, planning, and conducting an aggressive war against Ukraine. We also need to talk about war crimes separately,” she said.

Deputy Prosecutor General Hiunduz Mammadov, who was until recently in charge of his agency’s Department for Supervision of Criminal Proceedings for the Crimes Committed in Armed Conflict, said that since the establishment of a separate department in the Prosecutor’s Office for dealing armed-conflict-related crimes, Ukrainian law enforcement officers have been investigating into mercenarism crimes.

“To date, we have 32 criminal proceedings against more than 250 international mercenaries from 32 countries who took part in the armed conflict in the Donbas. Separate cases are underway regarding Crimea. As for the Czech Republic, we have identified 24 people who took an active part in the hostilities. We have registered these cases as illegal participation in armed groups, mercenarism, and in some cases as participation in terrorist organizations,” Hiunduz Mammadov said.

According to him, the Ukrainian prosecutor’s office is ready to assist in the investigations against Czech citizens, but so far no such requests came from the Czech prosecutor’s office to Kyiv. The Ukrainian side even offered to set up a joint investigation team, similar to the one working to investigate the downing of the MH17.

According to the participants in the online discussion, such cooperation would be useful for the investigation not only in the Czech Republic but also in other countries, because so far most of the verdicts passed in the Czech Republic are conditional precisely because of the lack of relevant evidence.

On the other hand, Mykola Hovorukha, Deputy Head of the Military Conflicts Department of the Prosecutor General’s Office, said that the evidence gathered by their Czech counterpart could be used in Ukraine and handed over to the International Criminal Court (ICC) if the ICC would be considering the case. He also noted that whenever Ukraine is investigating cases of recruiting foreign nationals in the Donbas, the prosecutor’s office sends a request to the relevant authorities in their countries, encouraging those agencies to cooperate in the investigation and exchange of information. But, according to Mykola Hovorukha, requests for legal assistance are a long and bureaucratically complex process.

The webinar participants also noted that the practices of Czech courts’ sentences can be used in the International Criminal Court, where Ukraine is dealing with multiple cases related to the war that Russia has been waging against Ukraine in the Donbas.

Read more:

- How Russia recruits Serbian mercenaries into the ranks of its fighters in Donbas

- Reputed Czech furniture company doing business in Russian-occupied Donetsk

- Czech Constitutional Court rules in favor of hotel ban on Russian citizens approving Crimean landgrab

- Czech president’s position on Crimea reflects a dangerous trend (2017)

- Portnikov: Is Crimea Ukraine’s Sudetenland?

- French politicians to visit Donbas to “support Russian army bombarded by Ukrainians” (2017)

- Russian puppet “LNR” opens “consulate” in Sicily and other overlooked stories from Donbas (2018)

- Kremlin-backed “DNR” to open fake diplomatic mission in Greece (2017)

- Kremlin-run “DNR” opens fake diplomatic mission in France (2017)

- Italian deputies demand explanation for “DNR office” (2017)

- Soviet tactics: “DNR” and “LNR” “embassies” pop up in the EU (2016)

- Fake monitors “observe” fake elections in Donbas (2014)

- The civil war hoax: words that fooled the world

- Czechoslovakia should be grateful to the USSR for 1968, Russian propaganda says

- Czech minority in Ukraine fears Russian aggression (2014)