Nonetheless, Ukraine saw two popular uprisings and successful revolutions that preserved democracy and prevented authoritarianism — in 2004 and 2014. Similar protests did not succeed in Russia or Belarus despite numerous attempts.

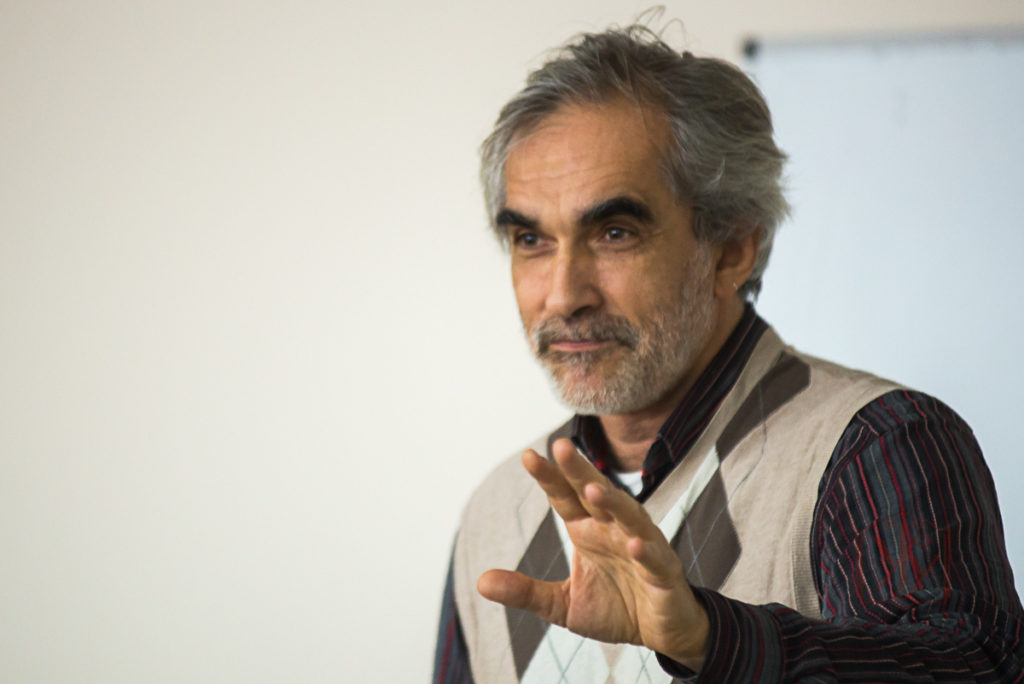

We asked Yaroslav Hrytsak, a prominent Ukrainian historian, why revolutions took place in Ukraine and not in Belarus or Russia; and where Ukraine and Europe in general are heading today.

The World Values Survey (WVS) is the world’s largest study of values conducted in almost 100 countries regularly since 1981. The study of values makes it possible to monitor significant shifts in the world cultural map as well as predict upcoming political changes or even revolutions.

Yaroslav Hrytsak, Ukrainian historian and public intellectual, has been analyzing WVS for a long time, as well as looking for a Ukrainian place in the European mental map from the historical point of view.

Significantly for Ukraine, over the last ten years a major shift took place in the country in self-expression values along one of the axes of the well-known Inglehart–Welzel cultural map.

This suggests the country is slowly recovering from Soviet cultural scars. Interestingly, Russia and Belarus underwent very similar, yet less radical trends. No successful democratic revolutions in those countries have followed yet, but attempts for such have intensified.

You have been closely watching and analyzing the World Values Survey. In terms of values, Ukraine is close to both Russia and Belarus. All three countries underwent a shift towards the values of self-expression. But in Ukraine they led to a successful revolution, yet not in Russia and Belarus. Maybe there are some other reasons beneath the surface?

The World Values Survey is just a compass and not a roadmap. WVS says something has appeared but is not necessarily bound to happen. We have looked at the results and it is especially interesting that significant changes have taken place in Belarus. And we thought something might happen. We talked about it with the Belarusians. But for that to happen, they need to have certain conditions, they need to have at least some minimal level of democracy. Or, so to speak, to have more than a single TV channel.

Ukraine managed to sustain its democracy, unlike Russia or Belarus. This happened twice, because Ukraine twice came out of the crisis without losing democracy.Ukraine came out the 1993 crisis with a peaceful transition of power, while Russia came out of it with tanks

The first time was when [second Ukrainian president] Kuchma came to power. Everyone said that [first president] Kravchuk would not give up power, and Kravchuk gave it up voluntarily.

This is very important. This triggered a mechanism of elite change in Ukraine. I always quote the words of late Russian historian Dmitri Furman from Moscow. He says that when this crisis took place in 1993 in Ukraine and in Russia, Ukraine came out of it with a peaceful transition of power, while Russia came out of it with tanks, when Yeltsin sent tanks to the White House [in Moscow].

After all, Ukraine had more temptations towards authoritarianism. And I believe that all young democracies have them. Ukraine had two temptations in 2004 and 2014, and twice came out with Maidans [revolutions]. It is very important.

Ingelgart's theory [according to which the WVS is conducted] says that if a minimal level of democracy exists in a country, chances for political change are higher. If the former is not the case, then the latter is difficult.These differences between Ukraine and Russia developed much earlier. These are the differences between political cultures that developed in the 16th and 17th centuries.

What Yeltsin did, what Putin did, and what I think Lukashenka did, is they burned civil society with napalm. And this has never happened in Ukraine. Civil society has never ceased existing in Ukraine.

So, the first important reason is that Ukraine managed to launch a mechanism for elite change in 1993 and 2004.

The second is that Ukraine has a very strong regionalism, which is not the case in Russia and Belarus. Regionalism means that no one can have a monopoly on power. There are several buttons and this is very important, because it creates, if not a real democracy, then at least democracy by default when nobody can rule single-handedly.

And last but not least, these differences between Ukraine and Russia developed much earlier. These are the differences between political cultures that developed in the 16th and 17th centuries, and maybe even earlier.

You can easily write Russian history without Cossacks -- but you can not write Ukraine's without Cossacks.

I'm not saying that it was all transmitted directly, but the Cossack myth has encrypted it, the Cossack myth which is the central myth of Ukraine. Which is not in the case for Russian myths.

Both Russia and Ukraine have Cossacks, but, as one expert said, you can easily write Russian history without Cossacks -- but you can not write Ukraine's without Cossacks.

In the Russian myth, the main event is that “we won World War II.” Because of strong power, strong Stalin, etc.

That is, I come to the point that motivation, including ideological motivation, is very important. That is also why Ukrainian nationalism is very important. It has this Cossack myth at its core. Because the Cossacks are not only about heroism, but also about certain political structures, self-government and self-organisation.

Historians always say that there is no one-factor explanation, but it is in Ukraine that all these factors come together and save Ukraine from the Russian or Belarusian scenario.

I was not the first one to use these historical arguments. The first was the famous scholar Ihor Shevchenko from Harvard. He said that the intensity of the use of the Ukrainian language and Ukrainian identity depends on the intensity of Polish influences in Ukraine. Not because they were Polish but because the west in Ukraine was dressed in a Polish coat.

The key is that it is the West where the church and the state split into two different poles of power. As these two poles fought with each other, it gave a chance to a third player who could use it. And independent structures such as free cities, universities, manufacturers, etc emerged as this third player.

The Cossack myth is essentially a myth of aristocratic democracy of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, only rewritten in the Ukrainian style. Simply put, "nothing about us without us."

Is it appropriate to talk about wider Polish influence, or just about institutional jurisdiction of the Commonwealth over Cossack-Ukrainians?

Of course, we are talking first about the institutions, but we also forget that the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth then evolved into Polish influences and we forget that the Polish factor existed in Ukraine at least until World War II in Galicia and Volhynia, and at least until the First World War elsewhere in Ukraine. We somehow forget that the main elite culture of central Ukraine and Volhynia was Polish culture, because most of the landowners in the Ukrainian part of the Russian Empire, whom we consider to be Russians, were not Russians. They were the Polish nobility.Few people know that Polish was the main language in Kyiv until the middle of the 19th century.

Few people know that Polish was the main language in Kyiv until the middle of the 19th century. We accept everything in the shadow of Russia, because Russia influences, Russia is an enemy, but we forget about the Polish factor. And my thesis is that Ukraine entered the shadow of Russia rather late. It is mostly a story of the last two centuries, under the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union... Before that, a major part of Ukraine belonged to different space.

You mentioned Ukrainian regionalism. Popular Ukrainian public intellectual Kateryna Botanova writes in her essay that Ukrainian culture and history tend to divide Ukrainians, so we can only unite pragmatically. You emphasize in your speeches that Ukrainians have always supported the idea of independence and the majority have always been ready to fight for Ukraine in all regions since 1991. The question is what Ukrainians are fighting for in reality. Whether for Great Ukraine, or just for a particular region but against Russian enslavement.

I will say this briefly: Ukrainians are ready to fight against a war. Ukrainians do not want to have a war at home, don't want to let it go further.

The peculiarities of Ukrainian regionalism are that we have strong regionalism, but no stable regions. Those regions are made of plasticine, they constantly change. The only stable region in Ukraine is Galicia. The rest of the regions are fluid, unstable, and do not have a clear regional identity.

That's why I always say that Ukraine is not a steel structure, everything can still be sculpted here, it is still young. On the one hand, this is a disadvantage, because it is difficult to rely on plasticine, but on the other hand, it has the advantage that you can sculpt, there is space.

Finally, I do not completely agree with Botanova, because sociology shows that Ukrainians are united in many ways. Most of all, they are united by the enemy. If there is an enemy, they unite instantly. This is very visible.

And if we talk about historical memory, the biggest difference between Ukrainians and Russians is their attitude towards Stalin. If in Russia Stalin is a hero who raised Russia from its knees and won the war, in Ukraine he is a villain. He is the man responsible for the Holodomor and other repressions.

What about Ukrainian revolutions in comparison to other revolutions during the past two decades? In one of your interviews, you say that there were many revolutions in the 2000s and 2010s, but Ukrainian revolutions are among those few that won. So the question is – why?

I have a hypothesis, but I do not have a firm explanation. I believe that there is such a general tendency in all revolutions that those revolutions that have a national dimension have a better chance of winning. For national patriotism, identity is the most mobilizing thing, the most emotional. This was very important for the Ukrainian revolution. One way or another, Putin and the Kremlin were present in this revolution, so for many it was a struggle not only for dignity but also for national dignity.Revolutions that have a national dimension have a better chance of winning. For national patriotism, identity is the most mobilizing thing

Here I make one caveat. The Ukrainian revolution, Euromaidan, could not win without nationalism, but nationalism did not win at that revolution. That is, I am not saying that it was a national revolution. It was about something else: the national question, nationalism was not the main thing but rather played an additional important mobilizing role.

This publication is part of the Ukraine Explained series, aimed at telling the truth about Ukraine's successes to the world, It is produced with the support of the National Democratic Institute in cooperation with the Ukrainian Crisis Media Center, Internews, StopFake, and Texty.org.ua. Content is produced independently of the NDI and may or may not reflect the position of the Institute. Learn more about the project here.