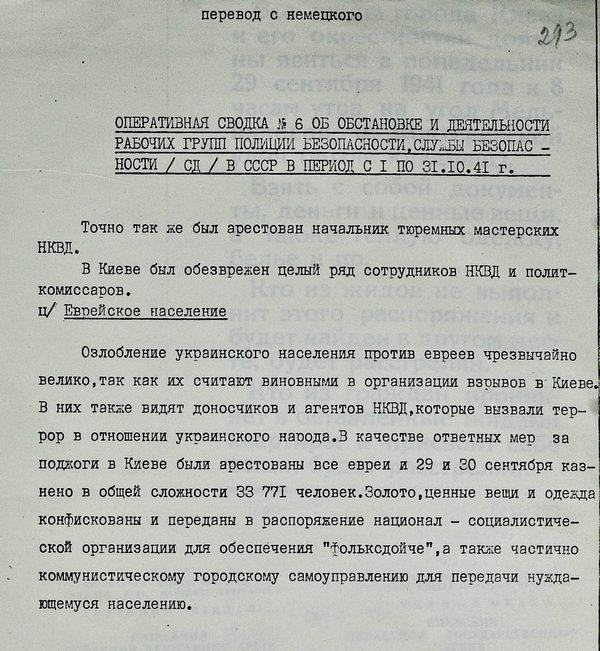

The massacre committed by the Nazis and local collaborators in the Babi Yar ravine on 29-30 September 1941, just 10 days after Kyiv was occupied during World War II, was the largest Holocaust mass execution “from bullets” in the Soviet Union. The victims included the patients of the psychiatric hospital, the Romani, Jews, Ukrainian nationalists, and other groups. During the first days, over 34,000 Kyivan Jews were brutally murdered in a ravine on the outskirts of the city.

The executions continued until the city was liberated from Nazis. Altogether, it is estimated that around 120,000 people were executed in a ravine which is now hidden under a street and a park which was literally built on bones.

1.5 mn Jews were killed on the territory of Ukraine during World War II, with most being shot in mass executions outdoors, like in Babi Yar. During the Soviet times that followed, the reality of the Holocaust was swept under the rug, as Jews were branded as anti-Soviet “cosmopolites.” To this day, the Holocaust and Babi Yar remain “undigested history” in Ukraine. Witness testimonies of survivors of those events allow identifying the exact location of the tragedy, as well as becoming a witness to those terrible events.

"We still do not know what they did to the Jews. Terrifying rumors are heard from the Lukianivske cemetery. But they still cannot be trusted. They say that the Jews are being shot. Those escorting them to the point where they were ordered to come saw that all the Jews walked through the ranks of German soldiers, threw their things, and then the Germans drove them forward..."

Iryna Khoroshunova made this entry in her diary on 30 September 1941.

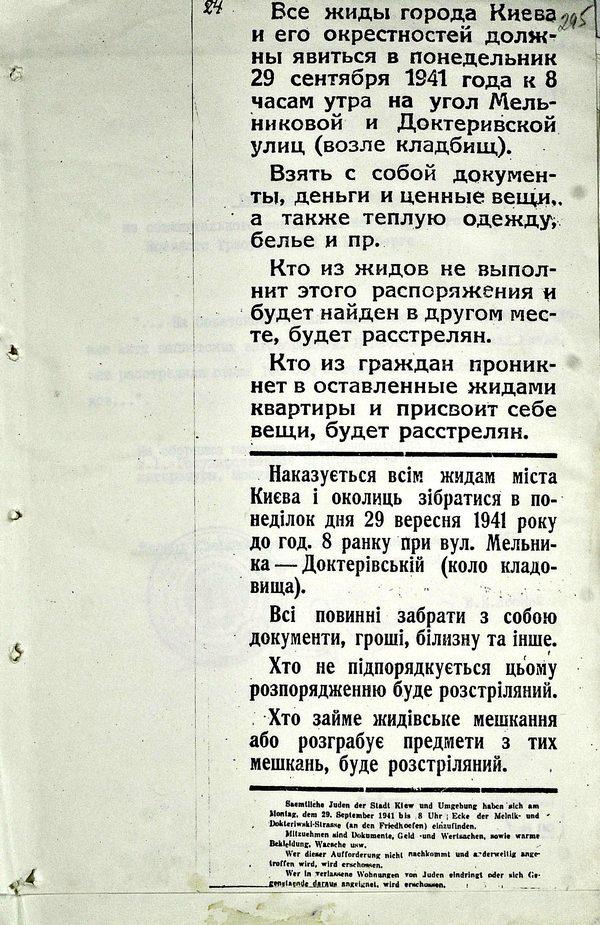

Two days before, on September 28, the following announcements appeared on the streets of Kyiv:

"All Jews of the city of Kyiv and its suburbs must appear on Monday, 29 September 1941, at 8 AM on the corner of Melnykovoi and Doktorivska streets (near the cemetery). Bring along documents, money, valuables, as well as warm clothing, linen, etc."

There were no such streets in Kyiv. But everyone understood that it was about Melnykova [currently - Yuriya Ilienka - Ed] and Dehtyiarivska streets.

Valia Terno was 10 years old on September 1941. And he knew nearly every bush in the vicinity of Babi Yar.

Early on the morning of 29 September 1941, he watched crowds of people from all over the city come to the Lukyanivka district, where it was located:

"We began to move with the column toward the cable factory. As we got closer to our destination, people became more anxious, the sighs more uncanny. In some cases, crying mothers, for the last time kissing their young children, handed them over into the hands of some kind people."

On 22 June 1941, on the day the Germans bombed Kyiv, Henia Batashova turned 17. She was born with her sister Lisa on the same day. There was also a younger brother Hryts, mom, and dad Jacob. Dad was soon mobilized. On 19 September, German troops entered Kyiv.

"I didn't believe uncle Nicholas.

In those days, he would often come to us, and walking with us outside, would talk to mother. This worried me a lot. One night I asked:

- Mom, what are you talking about? If you don't tell, I won't fall asleep.

Probably, mom realized that I had already grown up.

"Uncle Nicholas asks to believe him," Mom said. "If we are in danger, we can count on his help."

On 28 September, Hena and Lisa ran to read the German order. That day, two of their little sisters came from the nearby house. They had an awful premonition: "We will be killed."

"If I knew that death was waiting for you, I would have poisoned you all at home!" cried Hena’s mother through tears.

Uncle Nicholas came: "Tomorrow morning I will find out what is going on there. Until I return - do not go anywhere!"

In the morning, neighbor Mykola Soroka wasn’t there. It seemed dangerous to procrastinate to the Batashov family: failure to show up was punishable by execution.

On September 29, Hena’s mother, sister, and brother, Hryts left their residence at vul. Turhenivska 46.

***

Dina Pronicheva lived near vul. Turhenivska. In September 1941, she was 30 years old. On 29 September, she planned to escort her parents Myron Oleksandrovych, Anna Yukhymivna Mstyslavskyi, and sister Ida, and then return home to her husband.

"Large masses of people, including the elderly and children of all ages, were moving along the streets of the city, carrying with them mostly food and supplies. They were accompanied by relatives and acquaintances, Ukrainians, Russians, citizens of other nationalities. The streets leading to the gathering place - the area the cemeteries were completely crowded with people."

Dina Pronicheva's parents came forward and lost themselves in the crowd.

"I never saw them again," Dina recalled.

***

"If, God forbid, the worst happens and one of you will be lucky to be saved, then let it be Hryts," said one of Batash's neighbors.

Little Hryts was loved by everyone.

From Turhenivska, the Batashovs returned to vul. Artema [now - Sichovykh Striltsiv - Ed]. About half an hour later they reached the Lukianivka market.

Suddenly, uncle Nicholas appeared. He scolded us for disobeying him. He ordered to wait on the spot. And he ran forward to find out what was going on.

"And we forgot the salt after all! - Sister Lisa jumped. - How can we be on the road without salt!?"

Some people ran forward: "Faster! Faster! The echelons are waiting! Hurry!" Then trucks drove past the crowd. The trucks were filled with things. Upon the heap of things, almost reaching the tarpaulin sat the Germans, played the harmonica and laughed cheerfully.

"It kind of reassured us: can you be so cheery when people are being killed there?" later Henia Batashova will remember the last minutes on Lukianivka thus.

"Faster! You're late for the train!" - was heard again in the crowd. "We wanted to believe in some kind of train. Some people were trying to joke: what kind of cars would there be, first or second class?"

***

Valia Terno reached the intersection of Melnykova and Puhachova. Further, the road was blocked by the SS and the police: this is the way Valia remembered it. Together with their friends, they decided to run around the factories and cemeteries to take a look from the opposite bank of Babi Yar to see what’s going on there.

Some red-faced shaggy gaffer in the crowd authoritatively declared:

"Don't you know? The Jews will be shot in Babi Yar!"

Valia and his friends were stunned by these words and decided to flee. They went down the side streets to the ruins of the bombed Bolshevik plant in Shuliavka. From there the road went towards Babi Yar. At that time, it didn't even have a name. Then, vul. Dovzhenko paved in its course.

The boys almost reached what is now vul. Shchusieva but got into a human traffic jam: masses of people hit into yet another row of German soldiers. Nothing could be seen.

"Feeling that something terrible and irreparable would happen, people stood silently in a state of numbness," Valia Terno recalled.

***

In September 1941, Georg Biedermann served as the Hauptwachtmeister at the headquarters of the 3rd Company of the 9th Reserve Police Battalion.

During the interrogation after the war he claimed that

"at that time, a platoon of SS forces of about 35 people was provided to the disposal of the Task Force staff (...) the platoon of SS troops constantly went to executions (...) Everything that was in Kyiv was assigned to these executions, including, of course, EK 4a [Einsatzkommando - IP] and our 1st and 3rd platoons.

Before the executions began, I had to prepare food for everyone, especially for the SS troops. A large amount of alcohol was purchased, including rum, cognac and champagne (...)."

Alcohol did not help.

"Not many people were killed," recalled the driver of the Sonderkommando 4a, Victor Thrill. - I know only two schupo soldiers [Schupo/Schutzpolizei - security police] who were shot dead in their sleep by a colleague, who lost his nerve because of the executions...

The two comrades who were shot dead were buried properly with military honors, while the insane comrade shot himself and was buried somewhere in a nameless grave.

At that time, we all lost our nerves - some to a greater extent, others less. I couldn't eat for three days after the shootings, so much were my nerves out of order."

During an interrogation after the war, former SS Army Reservist in Sonderkommando 4a Henrich Heyer mentioned that at the end of September 1941, a whole company of young soldiers of the SS Army arrived to the kommando:

"...At this time, a mass shooting of the Jews of Kyiv that I knew about was taking place. Otherwise, these people would not be needed. I knew that these SS soldiers were appointed to shoot Jews because at night they were that they were raving and shouting something like "Nakolino or Nagolino!" [“on your knees” - Ed]. What this saying meant, I cannot say."

The meaning of this statement was explained by the SS Obersturmführer SS Häfner. For two days he controlled the activities of the SS firing squads:

"On the first morning, a squadron of the Special Forces Battalion and police from the Russia-South Police Regiment carried out the execution in the Babi Yar in various places of the ravine.

The Jews approached the pit in a single file. The first Jews were taken to the pit by SS soldiers. They were to kneel there, and in such a way that they bent their backs to their knees, bowed down their heads, and clasped their hands.

A gunner stood behind them and fired from the machine gun at close range in the back of the head or in the cerebellum. After the first Jews were shot, other Jews came to the pit in a single file. They had to kneel in the empty places left behind by those who were shot and were shot in the same way."

From the 27 August 1959 testimony of a former driver in the 4A Sonderkommando Fritz Hefer:

"It was a conveyor belt that did not distinguish between men, women, and children. The children were left with their mothers and shot with them.

I had watched all of this for a short while. Walking up to the pit, I became so scared of what I saw that I couldn't look there for long. In the pit I had already seen three rows of corpses, laid about 60 meters long. How many layers lay on top of one another, I could not see."

***

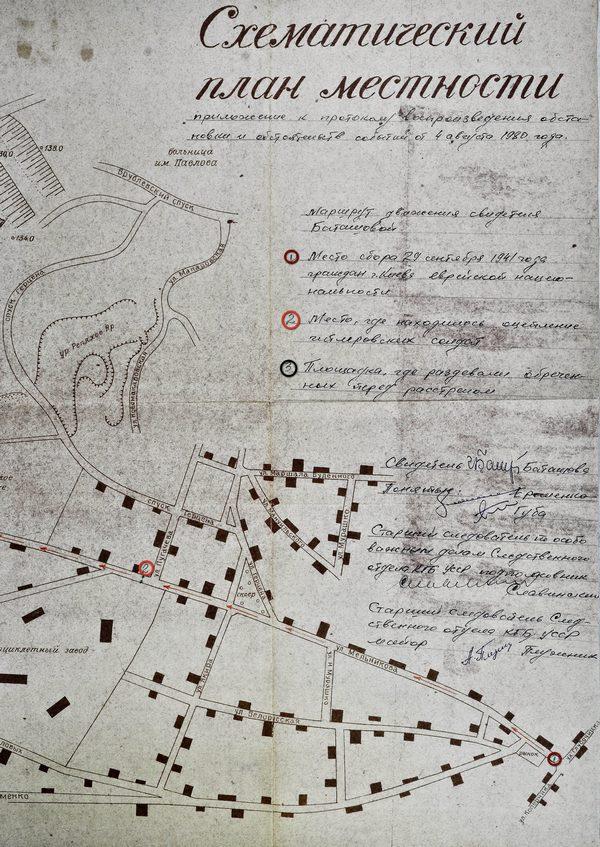

From the Protocol of the Reproduction of the Situation and Circumstances from 4 August 1980:

"At 20 meters northwest of the intersection of vul. Melnykova and Puhachova, witness Batashova showed places where a chain of Hitler’s soldiers stood, through which citizens passed through..."

This intersection was the last milestone where one could see familiar faces for the last time.

Georgi Brief was German in origin, taught at the Kyiv Polytechnical Institute. His wife Rosalia had Jewish roots. The last time they were seen together was here - at the intersection of Melyikova and Puhachova.

Then the witnesses mentioned how a tall, intelligent man, hugging his young wife, reached the chain of soldiers in black and green uniforms, and only then did he realize the hopelessness of his situation: "These are not Germans! I am German!"

He and his wife were dragged into the death corridor. No one saw them again.

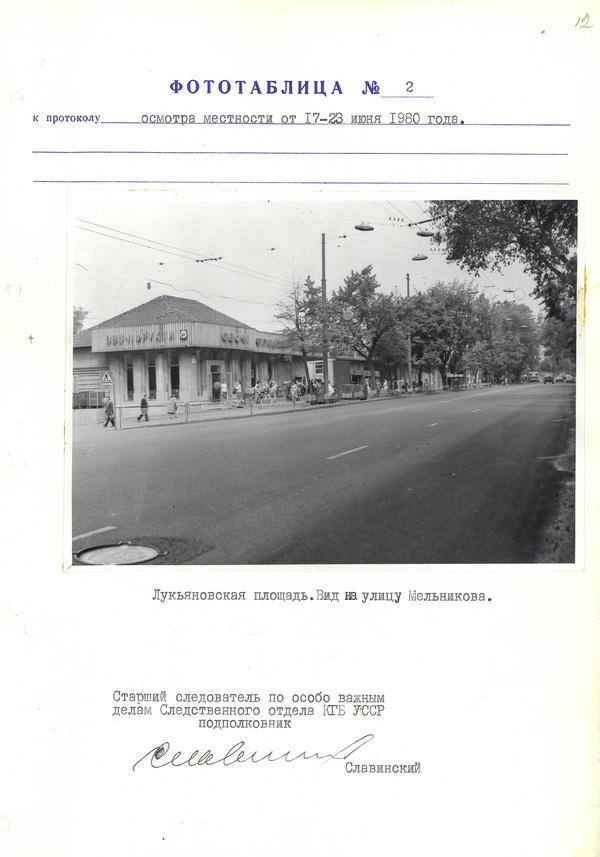

In August 1980, Senior Investigator on Particularly Important Issues of the Investigative Unit of the KGB of the Ukrainian SSR, Lieutenant Colonel Slavinsky walked down the road of death with Henia Batashova.

The investigators reproduced the circumstances of the events. Henia Batashova recollected the events.

At the intersection of vul. Melnykova and Simyi Khokhlovykh, another "outpost" was arranged:

"Anti-tank ‘hedgehogs’ were on both sides. Barbed wire stretched from them. The Germans stood close together with machine guns, holding opened bags.

“Personalausweis! Schatz! Sachen! (Documents! Precious things!)"

It became clear to everyone: this is not an evacuation!" Batashova recalled.

From the Protocol of the Reproduction of the Situation and Circumstances from 4 August 1980:

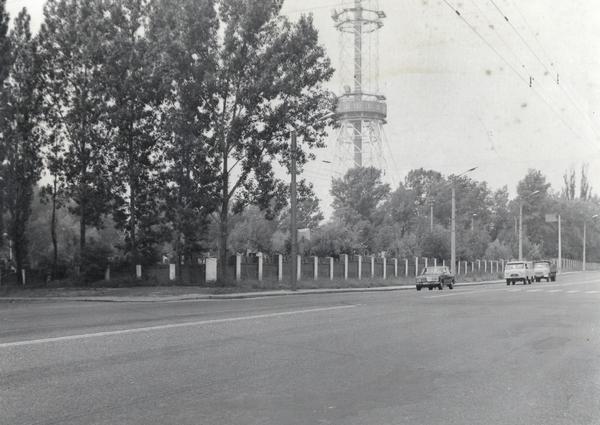

"Further leftwards to the south on vul. Simyi Khokhlovykh, 220 meters along the military cemetery fence, to the right along vul. Dorohozhytska in the western direction 450 meters along the military cemetery fence and the Kyiv Television Center..."

From the protocol of the interrogation of Dina Pronicheva:

"On the territory of the cemetery, the Germans took things and valuables from us and other citizens, and sent us in groups of approximately 40-50 people into a so-called corridor about 3 meters wide, formed by the Germans standing close on both sides with sticks, canes, and dogs."

From the memories of Henia Batashova:

"There were no roads except the pass to Babi Yar. Trees grew along it, and between them, the German gunmen with dogs stood in a solid corridor. After the documents and property were handed in, the Germans attacked the people, beating them with sticks…

People were no longer walking - they were running, knocking each other down. Their faces were like crazy."

The shots became louder.

"Now there was no doubt - we are being driven to death!

Lisa and Mom were crying. Hryts and I were petrified. Mom kept trying to protect us from blows.

(…)

We found ourselves on a meadow with trampled grass. It was hell in the full sense of the word.

On the opposite side of the meadow, surrounded by the Germans on all sides, was an earthen mound. Behind it, machine guns rattled ceaselessly. Passages in the embankment were dug at acute angles so that no one could see what was going on there."

From the testimony of Dina Pronicheva:

"I saw the Germans taking their children from their mothers and throwing them alive into the ravine; I saw women killed and killed, old people and children. Young people turned gray before my eyes."

From the memories of Henia Batashova:

"There was a baby lying on the ground. His mouth was open. But no one heard the screams of the baby in the terrible clamor. Perhaps the mother deliberately left the child, unable to endure seeing his death, and may have hoped that such a tot will be spared, won’t be killed.

The German approached and smashed his head with a stick.

(…)

I was running all beaten up, looking for my family and suddenly saw Hryts. He was standing next to a police officer.

‘Sir, I'm in no way to blame,’ my brother said. ‘Save me!’

I rushed to the policeman, begging to save Hryts. He shouted something and pushed us so hard that we fell.

When I came to my senses and stood up, Hryts was not there. I am once again running in this hell alone, looking for my family.

I came across a family who lived in front of our house. A mother with two children. The elder, five years old, hugged her mother's legs and shouted: ‘Mother, I do not want to die!’ The mother looked at me:

‘Henia, what does this all mean?!’

(…)

I saw very young people who turned gray before my eyes. Someone was laughing wildly, someone was hysterical, many seemed petrified, as if everything happening around them didn't concern them. Like living statues, they queued in front of the aisles naked to make some of their final steps.

I was already in the same condition. I was indifferent."

***

From the Protocol of the Reproduction of the Situation and Circumstances from 4 August 1980:

"From this place, witness Batashova passed with participants of the reconstruction 140 meters to the southwest along the roadway of vul. Melnykova.

Coming down from the roadway of the mentioned street, witness Batashova explained that a platform was adjoined to the northeast of place where the Nazis used to strip citizens who were doomed to death to their underwear.”

The "specified location" is the beginning of what is now vul. Oranzhereina. During the reconstruction of the circumstances of the Nazi atrocities in Babi Yar, Henia Batashova [..] was mistaken in her memories.

After the war, the entire territory was redeveloped. The upper part of Babi Yar was covered with clay pulp. Vul. Melnykova was continued further to where a deep ravine was located in September 1941.[..]

Judging from the pre-war topographic plans, descriptions of the other witnesses and photographs of Johannes Hähle, the meadow where the penultimate act of the tragedy took place was located 100-150 meters from the intersection of vul Dorohozhytska and the present Oranzhereina. A garage cooperative is now in its place.

The place where the events of the last act of the tragedy at Babi Yar - the shooting - unfolded, is a strip a few dozens of meters long between the roadway of present vul. Melnykova and the monument to the deceased.

[googlemaps https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/embed?mid=1rzbszbtfVRFZdMs6w8yCeUWooJoJqhFX&w=640&h=480]

It was here that the last journey of those who found themselves in Babi Yar, at the end of September 1941, ended.

Only a few people managed to escape. Henia Batashova and Dina Pronicheva were among those lucky ones.

***

"I don't know how much more I would live if I didn't see a girl from our house. It was thirteen-year-old Mania Palti.

She, like me, lost all her relatives. Her helplessness, which happens with girls of her age, her eyes filled with horror brought my strength back to me. Mania’s light eyes and blond hair suggested what we should do.

(…)

‘Let's try to escape,’ I said, ‘we look like Slavs.’

A police officer was standing nearby. We ran up to him, asked for help, explained that we were Russian, came by chance, out of curiosity.

‘I see that you are not Jewish,’ he said. ‘Jews or not Jews - march to the ravine!’

We ran away to the undressed people, circled the square, still hoping for a miracle. Stunned by the cries and shooting, I stared into the eyes of the policemen, looking for sympathy.

I placed zero hopes on the Germans. Finally, I saw one policeman. I felt something human in him. We ran to him.

‘I don't care who you are,’ he said quietly. ‘I'll help you.’"

***

On September 29, 1941, Paul Wertzberger arrived to Babi Yar on his motorcycle. He was a liaison to the 2nd Company of the 45th Reserve Battalion. He came to report to the commander of this company, Kreuzer.

The second character in this episode is Johann Koller, who was the personal driver of Kreuzer.

"Near the clothes lying near the ravine, two women stood, separated from the rest. When I passed them," Wertzberger recalled after the war," they said that they were Ukrainian and that I should save them. They literally attached themselves to me. Near this place was my friend Koller, who was Kreuzer’s driver.

I went with both women to Koller, and we both started discussing how we can save both of the women.

Whether the women were Jewish or were they really Ukrainian, I cannot say. We agreed that Koller would take both women out of the danger zone in his car. We were both aware of what awaited us when this rescue act would be revealed."[/box]

[...]

Henia Batashova then recalled that the police officer led them to the Germans standing by the car:

***

Dina Pronicheva's story ended more dramatically.

She also approached one of the police officers in Ukrainian and said that she had come here by accident.

The policeman took her aside, to a group of 30-40 such as Pronicheva.

"At the end of the day, a German officer with an interpreter approached our group, and the police, answering his question, said that we were escorts, got here accidentally, and should be released.

However, the officer shouted and ordered us also to be shot, not to let anyone get away, because we saw everything that happened in Babi Yar."

Dina Pronicheva was one of the last in the group heading to the execution.

"They led us to a protrusion above the precipice and started firing from the machine guns... When the machine guns fired at me, I jumped into the ravine alive.

It seemed to me that I was falling for eternity. I fell onto the corpses of people, into the bloody mass. Groaning heard from the victims, some were moving, some were injured."

Those who were to finish off the injured were walking down the ravine. Someone kicked Dina in the chest, stepped on her arm. Pronicheva withstood the pain and managed to hide that she was alive...

The hecatomb was being covered with soil. Dina began suffocating and shoved the sand away with her hand in the darkness. She climbed up to the surface of the ravine at night.

Dina Pronicheva wasn’t the only one to escape. In the ravine, she met a boy named Motia, about fourteen years old. During the execution, his father covered him with his body.

But at dawn, Motia, who could not resist fleeing from this terrible place as soon as possible, was quickly seen and shot by the Germans.

"Until evening, I stayed in a dumpster pit, and when it got dark, I got into a shed in some yard. In the morning, the landlady of that yard found me."

Dina said she had come from defensive works. But the bloodstained clothing gave no reason to doubt where she had come from.

After a while, the landlady's son came with a German officer.

"I recognized him as the Hitlerite who came with an interpreter on the first night and ordered us to be shot."

Pronicheva was first taken to a house where a group of such fugitives had already been gathered - 15-20 people. Then they were transported to another place. "On the way, I jumped out of the car, following me, another girl jumped out..."

***

On 2 October 1941, Irina Khoroshunova continued to record in her diary what she saw and what she thought:

"Everyone is already saying that Jews are being killed. No, they are not being killed, but have already been killed. Everyone, indiscriminately, old people, women, children. Those who were returned home on Monday were also shot.

So they say, but there can be no doubt. No trains departed from Lukyanivka. People saw cars carrying warm shawls and other things from the cemetery. German ‘accuracy.’ The trophies already sorted!

(…)

I am writing, and the mass murder continues in Babi Yar, of the defenseless, innocent children, women, the elderly, who are said to be buried half-dead, because the Germans are thrifty, they do not like to spend extra bullets.

The damn blue piece of paper presses into your brain like a hot plate. And we are absolutely, absolutely powerless!

(…)

Has there ever been anything like this in human history? No one could invent anything like this. I can no longer write.

It’s impossible to write, impossible to try to understand because we go crazy from the realization of what is happening...

The Jews are being chased while undressed. They are killed if they ask for water or bread. That's all. And we still live. And we do not understand why we suddenly have more rights to life, because we are not Jews. A damned age, damn ugly time!"

On 29 September 2019, hundreds of Kyivans marched down the Road of Death to recreate the last journey of the Kyivan Jews. This was the fourth such march.

Oleksandr Zinchenko is a historian and journalist living in Kyiv. He is one of the co-founders of Istorychna Pravda. Now he is the author and host of the television program "Declassified History" on the UA: Pershyi channel. Zinchenko has contributed to producing 12 documentaries and is a frequent author on historical topics in Ukrainian media.

Oleksandr Zinchenko is a historian and journalist living in Kyiv. He is one of the co-founders of Istorychna Pravda. Now he is the author and host of the television program "Declassified History" on the UA: Pershyi channel. Zinchenko has contributed to producing 12 documentaries and is a frequent author on historical topics in Ukrainian media.

Read also:

- Russian oligarchs push Babi Yar Holocaust Memorial project which discredits Ukraine – Zissels

- Kyiv honors memory of 34,000 killed in first days of Holocaust in Babi Yar

- How Soviet troops destroyed downtown Kyiv and killed Kyivans in 1941

- Understanding the Ukrainians in WWII Part 3. Of German plans and German collaborators.