Nuclear explosions in Ukraine

In total, the USSR conducted 239 peaceful nuclear explosions on its territory during in 1965–1988 under the auspices of the so-called Program 6 (“Employment of Nuclear Explosive Technologies in the Interests of National Economy“) and Program 7 (“Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy”).

Two underground nuclear tests were held in Ukraine (then, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic) in the 1970s.

Firstly, a 3.8-kiloton nuclear charge was detonated at a depth of about 2,500 meters in the west of Kharkiv Oblast to extinguish a fire at a natural gas field in 1972. It was the 28th Soviet peaceful nuclear test. The explosion codenamed Fakel (“Torch”) didn’t yield the desired results and the fire was later extinguished using usual methods.

In 1979, another industrial underground nuclear explosion rocked Ukraine, number 73 in the “peaceful atom” program. This time, a densely populated coalmining district in Donetsk Oblast was chosen for the test. A 0.3-kiloton nuclear charge was set off at the 903-meter underground operations horizon of the “Yunkom” coal mine. The explosion formed a glass chamber known as Object Klivazh.

The third nuclear explosion in Ukraine, this time an uncontrolled one, could have taken place at the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant amid the 1988 nuclear disaster. As some scientists believe, after the initial steam explosion which destroyed the reactor’s core, there could be a chain reaction of the nuclear fuel that caused the devastating second explosion which destroyed the roof of the containment building and released most of the nuclear fuel and fission products into the atmosphere. However, according to other theories, it could be either another steam explosion or an explosion of the huge amount of hydrogen, which could have been produced from the overheated water from the damaged cooling system of the reactor.

“Klivazh”

The history of coal mining in the Donetsk Basin goes back to more than 200 years, and some coal mines operating today are over 100 years old. As the coal mines in this area were deepened to deeper and deeper levels, the problem of coal dust bursts and explosions resulting from pockets of methane gas got worse.

At some point, the Soviet scientists suggested firing a relatively small nuclear explosive in a mine to assess whether shattering coal strata could be effective to release trapped gas and prevent dangerous underground blasts. Such an effect was earlier observed in the earthquake-affected areas.

The nuclear experiment was conducted in September 1979 in the “Yunyi Kommunar” (“young communard”) coal mine in the town of Bunhe then known as Yunokomunarivsk, a suburb of the Yenakiyeve city with 85,000 inhabitants. The “Yunyi Kommunar” or “Yunkom” mine lies about 40 km away from the regional capital, the million-plus city of Donetsk.

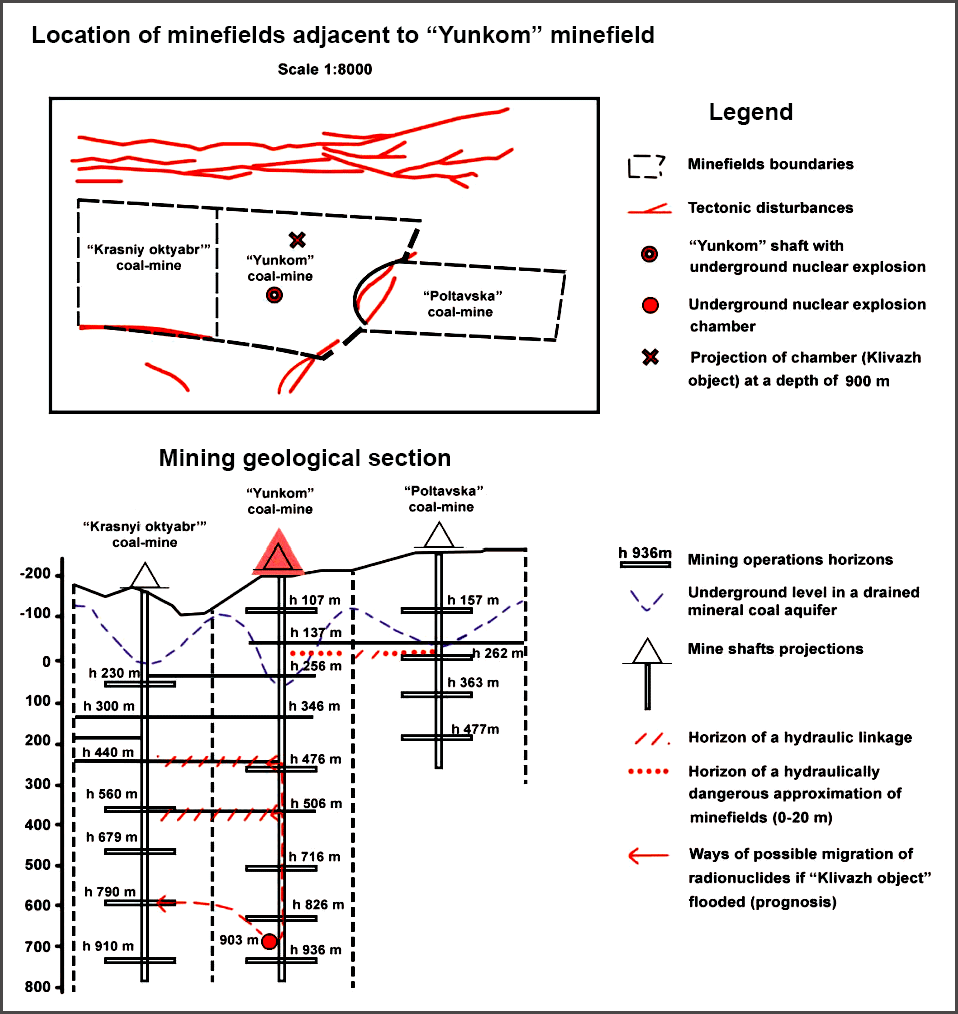

The nuclear device was emplaced in the “Yunkom” between two most outburst-dangerous layers. The particular location in a sandstone rock was chosen to assure that the resolidified melt containing about 95% of the radioactivity of the explosion would be insoluble in water. The explosion eliminated the dangerous blowouts in the radius of only about 150 meters, however, the number and intensity of any single burst reportedly reduced beyond that distance.

Radiation levels in the coal mined from the nearest layer 45 meters deeper than the explosion were reported to be insignificant.

The nuclear explosion formed an underground chamber of a vitrified glass-ceramic melt. The geological environment containing the chamber and an adjacent jointing zone was codenamed Object Klivazh or Cleavage facility.

“Yunkom”

The “Yunkom” mine was built back in 1911 by the Russo-Belgian Metallurgical Society as a Bunhe mine, named after Andrey Bunge, the head of the company. The mine fell under the control of the Bolsheviks in 1919, and in 1924 it was renamed as “Yunyi Komunar” or “Yunkom” for short. In 1940, “Yunkom” was recognized as the best coal mine of the USSR.

The mine was becoming more outburst-dangerous as deeper layers of coal were mined – 235 outbursts occurred at “Yunkom” in 1959-1979, killing miners in the 28 of the incidents.

The 1979 nuclear test reduced the number of such incidents at the mine, “Yunkom” operated for 23 years after the experiment up to 2002 when it was closed as not unpromising.

After the closure of the mine back in 2002, the Ukrainian government considered the possibility of flooding “Yunkom.” But local residents protested and the final decision was to maintain the pumping system and continue pumping water out. The locals of Bunhe believed that the explosion raised the rate of cancer and other diseases among the population. However, the officials asserted that the Object Klivazh was non-hazardous while sealed up and isolated.

With the coal production shut down, the mine’s pumps continued to pump shaft waters out for more than a decade to prevent flooding of the Object Klivazh.

Read also: Donbas threatened by mass radioactive pollution (2014)

“Yunkom” is linked to the adjacent mines, Krasnyi Oktyabr and Poltavska. Reportedly, both are being flooded since the beginning of the occupation.

As of 2008, Ukraine annually allocated approx. $45 mn for maintaining the pumping process at “Yunkom.” Now Moscow-installed occupation authorities of Donetsk have decided to save money on radiation safety of the region.

No radioactive hazard if flooded, assure the occupation authorities

The so-called ministry of coal and energy of “DNR” says a research revealed no hazard of radiation,

“After a complex scientific research carried out by leading DNR, Russian Federation institutes and a unanimous conclusion of subject matter scientists that the “wet conservation” of Object Klivazh will not lead to pollution of ecology [they said so – YZ] and radioactive danger to the town of Yunokomunarivsk [Bunhe – YZ] and to the region in whole, the [DNR] Ministry of coal and energy has come to a decision to flood the enterprise,” a statement reads.

Under the order by the “ministry,” the pumps will be fully stopped on 14 April at “Yunkom,” as of 22 March the “removal of equipment” was in progress. Removal of equipment in the occupied territory usually means cutting it for scrap.

The consequences are unpredictable and the effect may be irreversible, warn Ukrainians

Head of the department for ecological security of the Ukrainian Defense Ministry Maksym Komissarov has alerted at a briefing in Kyiv on 2 April,

“As you know, in the Soviet times at the [“Yunkom”] mine, an underground explosion was carried out, low-yield but still with the products of this explosion released underground. In case if the object will be flooded, the water may probably flush out the particles contaminated in consequence of the nuclear explosion, and they may seepage to groundwater. One can envision, what happens next – it’s very dangerous,” explained Komissarov.

He stressed that the issue requires an urgent decision, but the Ukrainian side has no leverage over the Donetsk occupation administration.

Environmentalist Oleksii Vasyliuk of ICF “Ecology-Law-Human” says that not a single environmental organization has been allowed to access any coal mine in the uncontrolled territory since the beginning of the Donbas occupation.

Another environmental expert Olga Denyshchyk, a senior freshwater officer of the WWF Danube-Carpathian Program, told Obozrevatel,

“Shaft waters run up, they may contain radionuclides. Definitely, this water is saturated with [ions of] iron, chlorine, salts, heavy metals. When such waters flood up, it ends up in [underground] horizons with water used for drinking and for watering, Then they go into the nearest river… finally, all of this will reach the Azov Sea.”

Deputy Minister for Affairs of Internally Displaced Persons Heorhii Tuka has commented on the plans to flood the “Yunkom” mine to Donbas.Realii, “For me, it was like a bolt from the blue. Because it’s a kind of suicide.”

“Repeatedly, we contacted the international organizations and they took part in attempts to solve this issue. Yet, like in the vast majority of cases, the key to success lies exclusively in the Kremlin,” told Tuka.

The deputy minister predicts that if drinking water will be poisoned, those local residents who remain in the occupied territory will mass-migrate to the free Ukrainian territory. “Roughly 150,000 a year,” assesses Tuka.

Not “Klivazh” alone

At the fourth year of the war, the “contact line” between Russian-hybrid and Ukrainian forces, home to many places of work, children’s playgrounds and schools, is described by UNICEF as “one of the most mine-contaminated places on earth.”

The Russian-hybrid forces had established a number of shooting and artillery ranges in the occupied territory and continue contaminating the area with remnants of ammunition, unexploded ordnances, POL far beyond the contact line.

Uncontrolled wildfires in summer threaten ecosystems of the mostly steppe region having only sparse forest zones. The Russian-hybrid forces cut wood lines which were grown to prevent steppe dust storms.

Read also: Ukrainian soldiers battle wildfires, along Russian-backed separatists, in war-torn Donbas

As coal mines shut down, illegal coal mining flourishes in the occupied territory, turning the steppe into lunar landscapes.

One of the most dangerous objects in the occupied Donbas is a radioactive waste storage facility in the west of Donetsk city, which is situated just on the front line and can be damaged any time amid the escalations hostilities, regularly erupting between the ceasefires.

The war endangers chlorine storage facilities, chemical plants, metallurgical enterprises, waste storage sites, coal mines, and other industrial facilities. At least 32 coal mines have already been flooded.

Read more:

- Donbas on the brink of environmental catastrophe (video)

- Everything you wanted to know about the Minsk peace deal, but were afraid to ask

- Who is who in the Kremlin proxy “Donetsk People’s Republic”

- Donbas beyond the war. Preserving the steppe marmot

- Coal from occupied Donbas is being sold to Poland – media

- Minister of Ecology: Russian troops are ruining Donbas’ environment

- Donbas is not only a zone of war, but ecological catastrophe as well

- Ecological disaster in Ukraine caused by Moscow’s invasion spreads into Russia, experts say

- The Chornobyl Dictionary: Too Hot to Hide