Some thirty-eight years ago, serving as a courier for the human rights movement—smuggling information out of the USSR and delivering humanitarian aid in—I visited one of my main dissident addresses in Moscow. As usual, Ira Yakir, daughter of the executed Red Army commander Iona Yakir and herself a prominent dissident, opened the door and whisked me in.

But this time she added: "Go to the kitchen, you will see a face well known to you." So I went, and indeed, I saw the live version of a photo I had so much internalized during years of campaigning for this person's release.

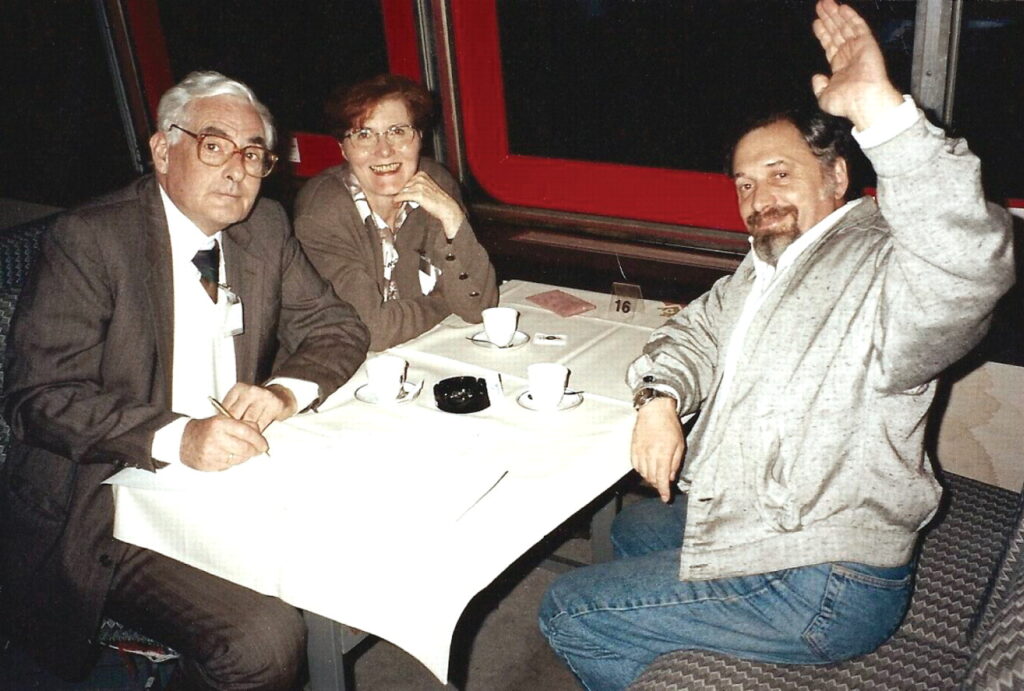

A face well known to me

Semyon Gluzman—Slava to friends—was in Moscow trying to have articles published about the political abuse of psychiatry.

In the Soviet Union, this was not a metaphor. Thousands of dissidents had been locked in psychiatric hospitals on fabricated diagnoses, most notoriously "sluggish schizophrenia"—a condition invented by the Moscow School of Psychiatry to explain why anyone would oppose the best sociopolitical system in the world.

Patients were drugged into submission, forcibly injected with substances that caused convulsions and excruciating pain, kept for years in wards alongside violent criminals. Roughly one-third of all Soviet political prisoners ended up in psychiatric facilities rather than labor camps.

The articles Gluzman brought to Moscow were remarkable. Having spent ten years in camp and exile for writing a diagnosis in absentia on Major General Petro Grigorenko—a decorated World War II veteran and professor of cybernetics at the Frunze Military Academy, who had turned dissident and was twice committed to psychiatric prison hospitals for defending human rights and the Crimean Tatars.

Grigorenko was among the few prominent voices demanding justice for the Crimean Tatars after Stalin's 1944 deportation of the entire population to Central Asia—an act of ethnic cleansing that killed nearly half of them in transit and exile. He urged the Tatars to demand the full reestablishment of their autonomous republic and to use every constitutional means available, from demonstrations to the press.

The Soviet state's answer was to declare him insane. Gluzman had now tried to analyze the origins of this Soviet system.

In 1971, then a young psychiatrist of just 25, he had examined Grigorenko's case files and concluded what American psychiatrists would later confirm: the general was entirely sane and had been hospitalized for purely political reasons.

For this act of professional integrity, Gluzman was sentenced in 1972 to seven years of harsh-regime labor camp and three years of Siberian exile.

While imprisoned in the Perm political labor camps, Gluzman co-wrote with fellow prisoner Vladimir Bukovsky A Manual on Psychiatry for Dissidents—a handbook teaching people how to avoid being diagnosed as mentally ill, published in Russian, English, French, Italian, German, and Danish.

In 1978, Amnesty International named him a Prisoner of Conscience. His case drew attention from The New York Times, the American Psychiatric Association, and members of the US Congress, contributing to a mounting international campaign that would ultimately force the Soviet Union out of the World Psychiatric Association in 1983.

From campaign to friendship

We discussed how to use his articles in that campaign, and this was the beginning of a long and deep friendship. The articles appeared in our book On Totalitarian Soviet Psychiatry, published in 1989.

At first, our approaches were very different. Slava was thirteen years older, having survived a decade of camp and exile, and he was very much a philosopher. I was a Western activist with still a black-and-white image of things, and hence our understanding of the reality and tactical approaches differed.

When in October 1989 the World Psychiatric Association held its World Congress in Athens—where the central question was whether to readmit the Soviet Union, which had withdrawn to avoid expulsion six years earlier—Slava made his first trip outside the USSR, coincidentally on the same plane as the Soviet delegation, which consisted mainly of the architects of the system of political abuse of psychiatry.

Our campaign team had an office in a hotel suite close to the conference site, and every morning Slava would come in around nine and sit on a chair next to the entrance for hours, watching me work.

He had never seen a campaign office, and it intrigued him. But it also convinced him that although our approaches were different, we could form a team and join forces.

"Nobody comes to Kyiv"

And so it happened. In the fall of 1990 he told me to stop traveling to Moscow and come to Kyiv instead. "Nobody comes to Kyiv, you can do anything there, much more interesting!"

And indeed, Kyiv was amazing. I didn't go to Moscow for fifteen years and instead came to Kyiv at least once a month. Slava's flat became the headquarters of the campaign to reform psychiatry in the—soon former—USSR, sitting around his kitchen table with two friends from Russia: Svitlana Polubinskaya, who authored the first normal law on psychiatric help in the USSR, and Yuri Nuller, a psychiatrist from St. Petersburg who had survived nine years of Kolyma, one of the deadliest corners of the Gulag.

What followed were decades of trying to pull psychiatry out of the Soviet marsh.

In January 1991, Gluzman established the Ukrainian Psychiatric Association, again with a unique approach. He refused to set up a dissident organization, realizing it would never become effective. So he invited the Chief Psychiatrist of Ukraine, the Chief Psychiatrist of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the Chief Psychiatrist of Kyiv to join the board.

This was, in the context of the time, almost inconceivable—these were people embedded in the very system that had incarcerated dissidents.

I will never forget the first board meeting. To me, all Soviet psychiatrists were still torturers of political prisoners, and to them I was a CIA agent—they had never met a foreigner before, let alone a very active anti-Soviet activist.

Trust grew only step by step. I will never forget the first time I went down into the psychogeriatric cellars of the Pavlov Psychiatric Hospital in Kyiv, where I saw and smelled Dante's Hell on earth. If I close my eyes now, I still see—and smell—the horrors of what transpired before my eyes.

When we left the cellars, the Chief Psychiatrist of Kyiv, Oleg Nasynnik, wept. He was in total shock. This was what decades of Soviet institutional psychiatry had produced: not just the political abuse of diagnoses, but the wholesale dehumanization of the most vulnerable.

People no longer remember where we came from, what the horrors of Soviet psychiatry looked like. Step by step, project after project, we started the long road to bring about change.

Hundreds of projects were implemented. We opened the first Psycho-Social Rehabilitation Center in Ukraine, the first Protected Living Environment. We set up the first family organization, the first consumer organization, developed the first training for psychiatric nurses. We even opened our own printing press and publishing house, Sphera, and published translations of 139 manuals and books on psychiatry, human rights, law, and other subjects—including the first edition of Anne Frank's diary in Ukrainian.

Gluzman was also one of the authors of Ukraine's 1998 Law on Psychiatric Care. When I now go through my computer, I am stunned how much we did.

Russia’s punitive psychiatry now spreads to kids in occupied Ukraine—their crime is being Ukrainian

Slava became my brother in arms, not only my close friend but also my educator. He taught me to look beyond the obvious, to try to understand the second, third, and fourth layers, the human factor, and the complexity of mankind. His memoirs, published a decade ago, are unique, because the book is not about heroism but about mankind—about the fear that is with us all the time but should not keep us from following our conscience and doing what is right.

I am eternally indebted to him, and had the honor and immense pleasure to work with him side by side for almost forty years.

Slava was not easy, as many great people are at times, but never in selfish pursuit. He lived for the cause and dedicated his whole life to the humanization and ethics of psychiatry, not only in Ukraine but on a global scale.0

In 2008, he received the Geneva Prize for Human Rights in Psychiatry at the World Psychiatric Association Congress in Prague—the same organization that had once sheltered his tormentors. And humor was our constant companion, which kept us going when facing injustice, opposition, or total lack of interest.

"This is my home, my freedom"

Russia's full-scale invasion in 2022 changed everything. Slava lived on the fifteenth floor of an apartment building in the Kyiv suburb of Obolon, and at one point the Russians were only several kilometers away.

He stubbornly refused to leave his apartment, and when I called to say we had found a refuge for him, he was very direct:

"If you ask me to leave my apartment once again, I won't pick up. This is my home, my freedom."

And I understood he was ready to die right there, in his fifteenth-floor apartment, in his space of freedom.

Age started taking its toll, as well as the consequences of ten years' imprisonment. In the Netherlands we call this "tropical years," which relates to the work of civil servants in the colonies: each year counting for two. The repeated and prolonged absence of electricity made him a prisoner in his apartment, his "freedom," and gradually he faded out of the public eye.

But every time I was in Kyiv, we would sit around the kitchen table, reminiscing about the past, talking about who had died, watching a whole generation of dissidents slowly disappearing. We remained optimistic—we were the "young kids on the block," we told ourselves. He a bit less than me, but still, we had many years to come.

When in 1991 Petro Grigorenko was posthumously rehabilitated—the psychiatric diagnosis that had imprisoned him officially reversed by a commission of psychiatrists from across the Soviet Union—Slava was called to Moscow to the office of the General Procurator. "Oh, you are still so young!" the latter exclaimed.

"Yes," Slava said with his typical irony, "you arrested me very young."

But alas, it turned out that we didn't have those many years, at least not together. The "tropical years" took their toll, and the hardship of living in a country at war being destroyed by Russia did the rest.

On 16 February 2026, Semyon Gluzman died at Oleksandrivska Hospital in Kyiv. He was 79.

The truth as currency

Slava left us, but only in flesh. He is still with us, in spirit, and we will continue the work he started in 1971 when, at just 25 years old, he chose his conscience over his career and wrote the diagnosis that would cost him a decade of his life. And I will write down all that he did and all that he accomplished, because the younger generations need to know where Ukrainian psychiatry came from.

They need to know their hero—who was so often ignored by Ukrainian authorities who could not stand his criticism and who saw no political gain in honoring a man whose only currency was the truth.