Three weeks before Trump met Putin in Helsinki, Europe's top human rights official agreed to help Jeffrey Epstein reach the Kremlin.

"I think you might suggest to Putin that Lavrov can get insight on talking to me," Epstein wrote to Thorbjørn Jagland on 24 June 2018.

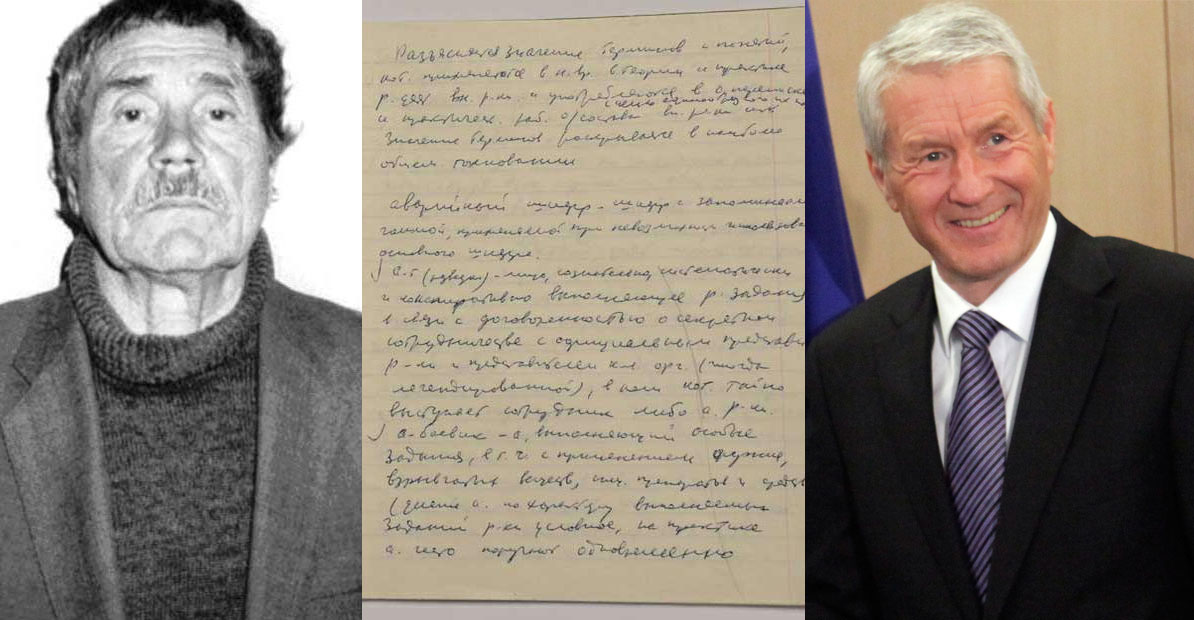

Jagland ran the Council of Europe—the continent's human rights watchdog. Epstein was a convicted sex offender who would die in a Manhattan jail cell awaiting trial on trafficking charges. And this wasn't their first contact.

Jagland spent years lobbying to restore Russia's voting rights after Crimea—while Ukraine, Poland, and the Baltics objected. KGB defectors named him codename "Yuri" back in the 1970s. He helped pick Nobel Peace Prize winners while trading friendly emails with a man who trafficked minors.

The 3 million pages of Epstein files released on 30 January 2026 land Jagland at the crossroads of questions that have dogged him for decades—and hint at something darker about how Russian influence burrows into Western institutions.

Jagland wasn't a fringe figure. He ran the institution that decides whether Russia belongs in European human rights bodies, helped choose Nobel Peace Prize winners, and shaped the debate over sanctions after Crimea. If Moscow had leverage over someone in that position—or even the appearance of leverage—it would explain patterns that have puzzled Ukraine's allies for years.

Who is Thorbjørn Jagland?

Jagland climbed Norway's Labour Party ladder to become Prime Minister in 1996, then Foreign Minister, then President of Parliament. In 2009, he took the top job at the Council of Europe—the continent's human rights watchdog—and held it for a decade.

He also chaired the Norwegian Nobel Committee from 2009 to 2015, awarding prizes to Barack Obama, the EU, and Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo. In March 2015, the committee demoted him as chairman in a move "unprecedented in the history of the award," according to The Local Norway. He stayed on as a regular member until 2020.

Few Europeans have accumulated more moral authority. And few have faced such persistent questions about Moscow.

The codename "Yuri": a Cold War mystery resurfaces

The questions about Jagland and Moscow didn't start with the Epstein files. They didn't even start with his decade at the Council of Europe. They go back to the Cold War—to a time when the KGB was cultivating young politicians across Scandinavia, and a rising star in Norway's Labour Party caught their attention.

As Euromaidan Press reported in 2017, the central Labour Party apparatus's contacts with the KGB remain "one of the major taboos in Norwegian politics," according to Norwegian journalist Alf R. Jacobsen.

In 1990, KGB major Mikhail Butkov—operating undercover as a journalist in Oslo—received orders from Moscow to reestablish contact with a Norwegian politician codenamed "Yuri." Butkov was already working as a double agent for British and Norwegian intelligence. He reported what he found: "Yuri" was Thorbjørn Jagland, then the powerful secretary of Norway's Labour Party.

According to the KGB telegram Butkov received, Jagland had been cultivated in the 1970s when he chaired the party's youth wing. He'd been "a useful source of political information" and "a channel for active measures"—including Soviet campaigns for nuclear-free zones in Scandinavia.

Oleg Gordievsky, the legendary KGB colonel who defected to Britain in 1985, corroborated the account. In his 1997 book A Blind Mirror, co-authored with researcher Inna Rogatchi, Gordievsky identified Jagland and then-finance minister Jens Stoltenberg as KGB "confidential contacts"—assets who provided information without signing formal contracts.

Jagland dismissed the claims as routine diplomatic activity. No charges followed. But the allegations resurfaced in Norwegian media for decades—including in 2011, when journalists accused Jagland of helping suppress a book that would have exposed more KGB operations in the Nordics.

The suppressed book was real. Vasili Mitrokhin, a KGB archivist who defected to Britain in 1992, had smuggled out what the FBI called "the most complete and extensive intelligence ever received from any source." His notes formed the basis of two books with Cambridge historian Christopher Andrew. A third volume—focused on the Nordic countries—was planned but never published.

Norwegian journalists found that in January 2001, the Norwegian Police Security Service sent a report to the Ministry of Justice identifying 16 Norwegians with KGB ties—10 of whom had worked in the Foreign Ministry, which Jagland led at the time.

Council for Russia: how Jagland turned a blind eye

After Russia seized Crimea in 2014, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) suspended Russia's voting rights. Moscow retaliated by withholding its €33 million annual fee.

What followed was a grinding campaign to let Russia back in. No one pushed harder than Jagland.

Despite the occupation of Crimea, the war in Donbas, and severe human rights violations on the peninsula—including repression of Crimean Tatars, disappearances of activists, and militarization—Jagland consistently advocated for the return of the Russian delegation to PACE. From 2016 onward, he increased pressure within the Council of Europe to lift sanctions on Russia, even though it was Russia that had violated the organization's founding principles.

In January 2018, he told PACE that Russia's war in Ukraine wasn't grounds for punishment—claiming Moscow hadn't violated the European Convention's core articles. The Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group noted he was ignoring documented torture in occupied Crimea.

He blocked Ukraine's offer to cover Russia's unpaid dues, according to Ukraine's ambassador to the Council of Europe Dmytro Kuleba, who called it Jagland's "targeted policy."

An academic study in the European Convention on Human Rights Law Review later concluded that Jagland "actively sought the reversal of PACE's sanctions, despite Russia's failure to comply with PACE's resolutions."

In June 2019, PACE caved. Russia got its voting rights back, no conditions attached. Seven delegations walked out.

Ukrainian deputy Volodymyr Ariev, who headed the Ukrainian delegation in PACE at that time, openly opposed Russia's return and called Jagland a conduit of Russian influence. According to Ariev, fighting the FSB network within the Council of Europe under Jagland cost him his health.

"I hope the Council of Europe will establish a separate body to conduct a detailed investigation into the network of Russian intelligence services that operated in PACE for years," Ariev said after the documents were published.

They called him “Yuriy”: the KGB past of the man who advocates restoring Russia at PACE

"We have had wonderful days:" the Epstein-Jagland connection

Jagland and Epstein go back years. As early as January 2013, Epstein called Jagland "a great friend" in emails, according to Norwegian newspaper Dagens Næringsliv.

Trending Now

In June 2016, before Trump's electoral victory later that year, Jagland wrote to Epstein: "If Trump wins in US I'll settle on your island." That island was Epstein's Caribbean estate, where prosecutors said he trafficked minors.

In April 2017, Jagland sent get-well wishes: "We have had wonderful days."

Bill Gates and Epstein met with Jagland at his residence in Strasbourg on 27 March 2013. When Nobel Committee chair Berit Reiss-Andersen asked members in 2019 whether any of them had contact with Epstein, Jagland said no. He changed his answer the following year, calling it a "misunderstanding." Reiss-Andersen told DN it was "unfortunate" she'd passed along an answer that "turns out not to be correct." In February 2026, Jagland admitted to Aftenposten he had shown "an error of judgment."

But it's June 2018 that matters most. Epstein wanted a line to Sergei Lavrov. He pitched his value:

"Churkin was great. He understood Trump after our conversations. It is not complex. He must be seen to get something—it's that simple."

Vitaly Churkin was Russia's UN Ambassador until his death in 2017.

Translation: Epstein was selling himself as a Trump whisperer for the Kremlin. And he was using Europe's top human rights official as the door.

Norway's Economic Crime Authority has now opened an investigation into whether the released documents warrant a probe into economic crimes.

1,055 mentions of Putin: the Epstein-Russia pattern

Jagland isn't an isolated data point. The Epstein files are filled with Russian connections.

Putin's name appears 1,055 times in the correspondence. "Russia" shows up nearly 5,900 times. One FBI report calls Epstein "President Vladimir Putin's wealth manager," according to Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk.

According to the US Department of Justice files, Epstein actively sought a personal meeting with Putin from 2010 to 2018. He tried to obtain a Russian visa, discussed economic projects and investments, and explicitly asked whether he should contact his "friends of Putin." In 2011, he wrote to Emirati businessman Ahmed bin Sulayem that Putin may come to the US, so Sochi, as a meeting place, was unlikely.

Senator Ron Wyden's Treasury investigation found Epstein moved "hundreds of millions of dollars" through Russian banks now under US sanctions—transfers "correlated to the movement of women or girls around the world."

Former NSA counterintelligence officer John Schindler wrote in the Washington Times that "the heart of the Epstein saga was a clandestine intelligence operation devoted to compromising and blackmailing rich and powerful people." Epstein, he concluded, "was clandestinely involved with multiple intelligence agencies."

Poland has now opened an investigation into "the increasingly likely possibility that Russian intelligence agencies co-organised this operation."

Honeytrap empire: Epstein files reveal deep ties to Belarusian and Russian individuals, including an FSB-trained business advisor

What this costs Ukraine and its allies

For three years, Ukraine has watched Western support stutter, weapons deliveries delayed, sanctions half-enforced, and red lines erased.

The usual explanations are bureaucratic inertia, economic self-interest, and fear of supposed nuclear escalation.

The Epstein files suggest another factor—one that Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk now considers a national security threat. On 3 February 2026, he announced a formal investigation into the "increasingly likely possibility that Russian intelligence services co-organised this operation."

His warning was blunt: "This can only mean that they also possess compromising materials against many leaders still active today."

When the head of Europe's human rights body agrees to courier messages from a convicted sex offender to Putin's foreign minister—then spends years fighting to restore Russia's standing after Crimea—the question isn't whether kompromat exists. It's how much is already shaping decisions.

These actions became part of a broader trend that made Europe dependent on Russian oil and gas, while Crimea was turned into a Kremlin military base in the Black Sea, serving as a launchpad for Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

"The most useful stuff is the stuff we don't hear about," Chatham House analyst James Nixey told CNN. "Information is only useful if it's not being used."

Jagland told Norwegian media he "strongly distances" himself from what's emerged about Epstein's private life.

His Epstein contacts? "Part of normal diplomatic activity."

Read also

-

CoE Secretary General Jagland now openly lobbies for return of Russian delegation

-

No limits for Russia: how PACE agreed to lift sanctions on the aggressor

-

The treason of Europe: PACE adopts resolution allowing to lift political sanctions against Russia

-

Russia’s return to PACE would end Council of Europe as human rights instrument – Ukraine’s ambassador to CoE