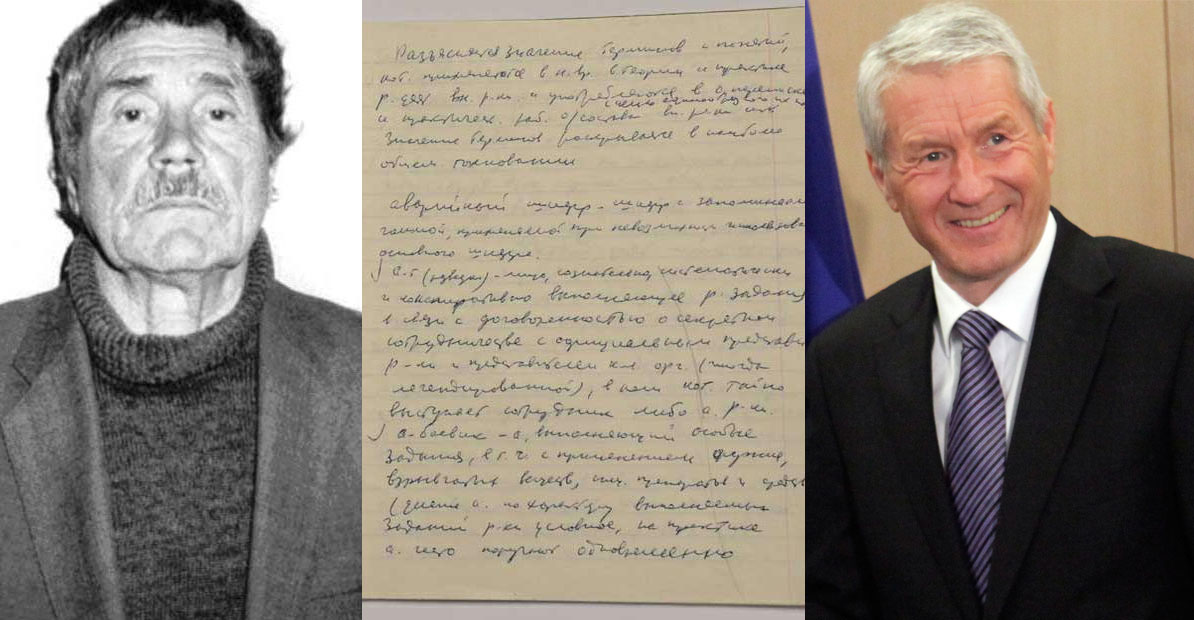

The recent campaign by Secretary General of the Council of Europe Thorbjørn Jagland to reinstate the Russian delegation at PACE by removing political sanctions imposed on it after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and covert war in eastern Ukraine has left many questioning its motives. Some say that this is a way to appease the aggressor – throwing Ukraine off the deck to improve relations with Russia, hoping that the threat will never come to their more westlying countries. Some have suggested that PACE is eager to receive the cash with which Russia is blackmailing the organization by withholding its membership fees which it should pay as a member of the Council of Europe. Yet others seem to accept Mr. Jagland’s reasoning that this is a necessary step to help ordinary Russians appealing to the European Court of Human Rights, as Russia has hinted it will not recognize ECHR rulings, should the political sanctions imposed on the country remain in place, and prevent the country from participating in the next vote for ECHR judges – which is, essentially, another form of blackmail.

Less known is the fact that this is not Mr. Jagland’s first questionable dealing with Moscow.

Assigned the codename “Yuriy” and treated as a valuable source by the KGB in the late 1970s-early 1980s while serving in the Youth organization of the Labour Party he later led, in 2011 Mr. Jagland was accused by Norwegian journalists of contributing to stopping the release of a book exposing the KGB’s operations in Nordic countries. Mr. Jagland, who then headed both the Labour Party and Norway’s Foreign Ministry, downplayed the role he had for the KGB, denied being aware of the release of such a book at all, and dismissed warnings about two employees of his ministry of whose KGB connections he was warned. But recently declassified documents in Cambridge prove that in 2001 he was informed of reports by British intelligence that not two, but 10 employees inside the Norwegian Foreign Ministry had been in relations with the KGB. The Norwegian police recommended the Foreign Ministry take action, as the threat these employees carried was “still real.”

It is now possible to say that, at the very least, Mr. Jagland underestimated the threat and did not acknowledge the warnings he was given by the police. Till this very day, the relations of the top-management of the Labour Party, which in 2011 was the governing party with Jagland as its leader, with the KGB remain a taboo subject in Norway.

While there is no proof that Mr. Jagland was engaged in criminal activities in connections with the Russian officials who turned out to be KGB officers, the question worth asking is: was it wise to engage in “dialogue” with organizations representing hostile powers in foreign countries with repressive rule, who were there only to infiltrate society? With his initiatives to return a militarily resurgent Russia to the “dialogue table” in PACE, Mr. Jagland shows he draws no lessons from the history of the KGB’s operations in the West.

Norway’s Labour Party: a KGB target

The Nordic states were a primary target for infiltration by the Soviet Union during the Cold War era. Socialist governments, proximity to the Soviet border all made them a fertile ground for espionage and active measures. Norway, where Mr. Jagland hails from, was of particular interest, as it shared a border with the USSR. The main task of the KGB was to grow contacts with the Labour Party. Then, long-standing Prime Minister Einar Gehardsen were among those close to Soviet embassy officials, and even former Labour Party leader Reiulf Steen and Environment Minister Thorbjørn Berntsen were viewed as contact persons by the KGB and assigned their own cover names.

It appears that many of those who had contacts with the KGB hold senior positions in the Norwegian government to this day, and the nature of their relations with the KGB remains hidden from public scrutiny.

As journalist Alf R. Jacobsen, who revealed the KGB contacts of Jens Stoltenberg, now serving as NATO Secretary General, in a NRK Focal Point TV program in 2000, wrote: “The central Labour Party apparatus’ contacts with the KGB are one of the major taboos in Norwegian politics.” Jacobsen wrote that his program faced the condemnation of not only Stoltenberg but the press’ leading commentators, and even his boss.

There is much pointing to Mr. Jagland’s central role in maintaining this state of affairs.

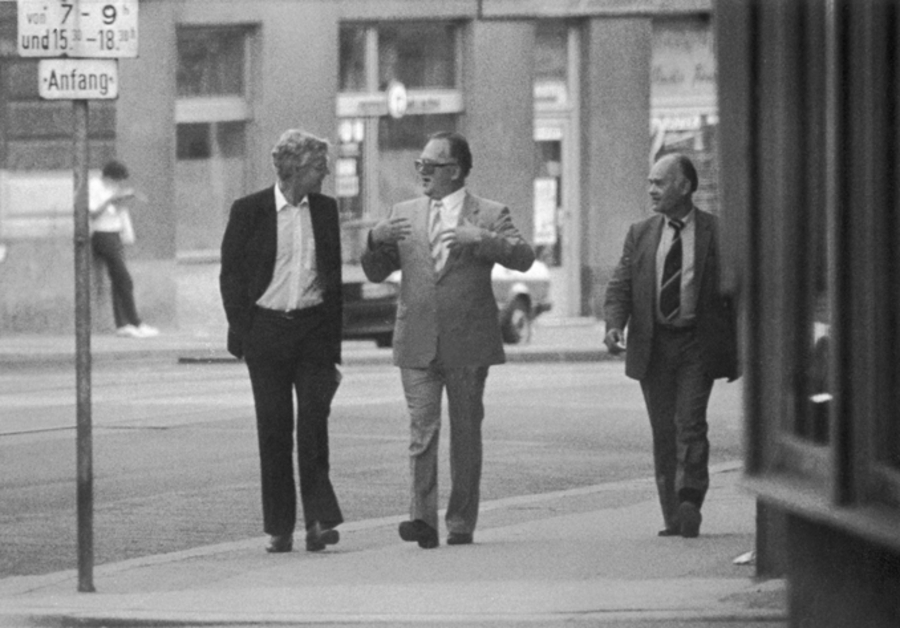

Thorbjørn Jagland’s relationship with the KGB started in the late 1970s-early 1980s, when he was the chairman of the Labour Party youth organization and was employed in the party secretariat, Norwegian press reported in August 1997. Then, the KGB gave him the codename “Yuriy.” These disclosures came from KGB defector and double agent Mikhail Butkov, a former KGB major who came to Oslo in 1989 and defected to Britain in 1991, and former KGB colonel, defector Oleg Gordievsky, who in the co-authored book “Blind mirror” published in 1997 said Mr. Jagland and Norwegian finance minister Jens Stoltenberg were both contact men for the KGB in the late 1970s. The term used for them was “confidential contact,” meaning they provided political information to the KGB operatives, but had not signed any sort of written contract.

Butkov was sent to Oslo to reestablish contacts severed following the major spy scandal in 1984 with the uncovering of Arne Treholt, a former Labour Party politician and diplomat convicted of high treason during the Cold War. It was Butkov who uncovered the politician behind the KGB codename “Steklov” – Jens Stoltenberg, who currently serves as Secretary General of NATO. Butkov’s discovery could very much have saved Stoltenberg’s career, as it led to the Norwegian security police warning Stoltenberg that what he perceived as regular political talks were in fact a carefully planned attempt to wrap the then upcoming Norwegian prime minister candidate into the KGB network. Stoltenberg said that after being informed of this, he broke of all contacts with the Russian diplomat.

In 1990, Butkov was tasked to establish contact with “Yuriy,” Thorbjørn Jagland, the then powerful secretary of the Labour Party.

The KGB’s “confidential contacts” in Norway uncovered by Butkov had attempted to portray their relations with the KGB as insignificant. Jagland said he was just doing his job, which meant regular contact with foreign embassy personnel, including Russians, and that he reported the contacts to the Labour Party leadership and intelligence officer Trond Johansen.

At the same time, it is clear, based on reports from Butkov and other defectors, that the KGB officers perceived the situation differently. Steklov’s folder in the KGB, for instance, was of the type DOR – “Delo Operativnoi Razrabotki.” Such directories were normally reserved for individuals who were at an advanced stage of cultivation or were already considered as one of the KGB’s “confidential contacts.” The KGB officers clearly saw the men as candidates for collaboration with the Soviet secret service.

The Mitrokhin archives and the spybook that never came

However, both Gordievsky and Butkov had only brief access to the KGB files on the Norwegians. The handwritten notes of ex-KGB archives chief Vasily Mitrokhin, which became a goldmine for intelligence organizations in many countries for studying the Soviet Union’s operations in the West after the man defected to Britain, could have allowed Norwegian KGB truth-seekers to go further. The notes formed the basis for the British Secret Intelligence Service, also known as MI6, to share the revelations with the secret services of 36 countries.

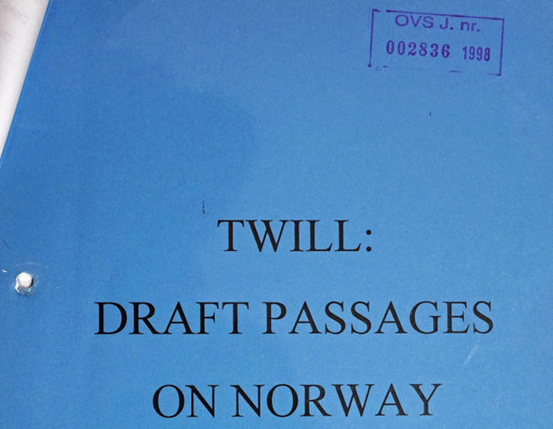

Mitrokhin’s handmade copies from the central KGB archive became the base of two books co-authored by Mitrokhin and the chief historian of the MI5 (British security service) Christopher Andrew, Sword and the Shield (1999) and The World Was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for the Third World (2005), giving details about the Soviet Union’s clandestine intelligence operations around the world. Evidence uncovered by Norwegian journalists points to there being plans for the release of a third book, focusing on the Nordic countries. However, it never saw the light of day, and according to reports by Norwegian investigative journalists, Mr. Jagland played a key role in this.

In 2001, Norway’s largest newspaper, VG, reported on a forthcoming book that would divulge previously unreported information about Norwegian politicians’ Cold War-era KGB ties; ten years later, in 2011, another major daily, Dagbladet, reported that the book’s publication had been stopped by heavy diplomatic means, that the book showed that Treholt wasn’t the only KGB spy in Norway, and that there were some that were still inside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Labour Party. One name of a spy was also in the East German Stasi archives.

Dagbladet’s unnamed sources familiar with the book said that the top management of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Labour Party, both led by Mr. Jagland at the time, and the Norwegian intelligence had been involved in stopping the release of the book. As the British Intelligence cooperates with its NATO allies, it had to comply. At the time, Norwegian historians were still striving to release the source material of the Mitrokhin archives, which contain a lot of material about Scandinavia, according to Mitrokhin in an interview with Berlingske Tidende.

In the midst of the confusion, the author Christopher Andrew, told the journalists then that he never intended to write such a book, implying that it didn’t exist. However, the former chief of the Norwegian Police Security Service Per Sefland told Dagbladet in 2011 that he knew about the book and that his service had prepared a report on the information inside it. In 2001, the report was handed to the Ministry of Justice, the Attorney General, and the Foreign Affairs Council.

After the scandal broke out in 2011, Thorbjørn Jagland denied that he ever knew of a book. However, he did say he was aware that two persons working in Norway’s foreign ministry were mentioned in Mitrokhin’s archive, but both were cleared by the ministry’s top administrator, who “looked into this and determined there was no reason to pursue the matter.”

Adding even more to the confusion, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, on its part, stated in a press release that not two, but “three people who at that time worked in the foreign service were featured in the historical material” of the Mitrokhin archives.

They found that the Norwegian police had already known about Andrew’s upcoming spybook in 1997. The following year, actors in the publishing industry were also involved in the project, and in April 1998, the Monitoring Center (OVS) received the first draft texts that addressed Norway, therefore dispelling any doubts about the book’s existence.

The Cambridge materials also contain the report the Norwegian Police Security Service sent to the Ministry of Justice in January 2001, which revealed the identities of 16 Norwegians and recommended measures against the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, led by Jagland:

“Of the 16 persons identified and discussed below, there are 10 who have been or are still employed in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Accordingly, it is imperative that Police Security Service, based on the information from the Mitrokhin archive, informs the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that this threat is still as real and that the orientation is given in such a way that the ministry’s management alone or in cooperation with the Police Security Service, makes sure that this knowledge is passed on to all of its employees.”

It is unknown how the Norwegian Foreign Ministry and Ministry of Justice responded to this threat. Commenting to TV2, the Foreign Ministry stated that the prosecuting authorities are responsible for dealing with this information, and that it’s “not natural” for the Foreign Ministry to further comment on the matter.

In the same report, TV2 states that a Police Security Service survey from February 2000 reveals that British Intelligence sent information on 35 Norwegians with links to the KGB in the 1990s. But TV2’s review of Mitrokhin’s notes in Cambridge shows at least 40 are described.

Per Sefland, the chief of the Police Security Service during 1997-2003, told TV2 he believes Norwegian KGB agents have escaped, not only Ministry of Foreign Affairs officials, but also politicians. “Posterity may well come to show that you have been a little too neglectful towards intelligence risks,” he said.

In several countries, Mitrokhin’s information led to spies, litigation and public investigations. In the neighboring Denmark, Anders Fogh Rasmussen’s government granted $ 10.5 mn to establish a Center for Cold War Research, in result of which a book called “Wolves, Sheeps and Guardians” was published in 2014. But in Norway, Mitrokhin’s revelations led to silence. The KGB spies got away because somebody wanted them to get away.

Lessons ignored?

The historian Roy Vega asked the provocative question: which senior Labour Party members in Norway didn’t have close contacts with the KGB? After the collapse of the Soviet Union, these issues were swept under the rug. The Labour Party avoided uncomfortable questions, insisting that their contacts were innocent and simply part of a regular diplomatic exchange.

Thanks to the KGB officers, and the contacts that engaged in a “dialogue” with them, the Soviet authorities had extensive knowledge of the countries which they tried to influence, being informed of all the local intrigues, and having detailed files on the politicians, journalists, and intellectuals.

Attempts to shed light on these operations in Norway meets resistance to this day. After uncovering the details of Jens Stoltenberg’s KGB-“Steklov” alias, journalist Alf R. Jacobsen wrote of a violent reaction, in which politicians and journalists made attempts to frame the case as insignificant and highly likely fictional. According to Stoltenberg, Dagblad’s disclosure of the book which was halted was met with a similar reaction.

“No one can say it was a criminal offense. We know too little to say that. But what we need to figure out is why so many people over the long term found it right to maintain contact with people who were not at all interested in ‘political bridge building’ but who had only one goal: to recruit agents who could be relieved of sensitive information to the benefit of the Soviet state – consciously through money and pressure, unconsciously through flattery and psychological shadow games,” Jacobsen was careful to note.

Much of the same tactics are being used in Russia’s disinformation campaign against the West today, in which grievances and divisions are exacerbated to wreak chaos and undermine genuine democracy. But, unfortunately, the right questions are still not being asked. Perhaps we can give it a shot immediately:

Why does the Secretary General of the Council of Europe find it right to insist on a “dialogue” with a country ignoring all resolutions of the Council of Europe, which uses political and financial blackmail to regain access to a platform which it will use not for political bridge building, but in order to undermine Europe itself?

We have no answer yet.

Read also:

- PACE adopts resolution allowing to lift political sanctions against Russia

- How the head of PACE became Putin’s lackey

- PACE calls on Russia to release Sentsov and other Kremlin hostages

- Historic PACE resolutions condemn Russian aggression, rule out elections in occupied Donbas

- Russia’s participation in PACE meeting protested in Madrid