Between the first and second day of US-mediated talks in Abu Dhabi, Russia launched nearly 400 drones and missiles at Ukraine. Over a million people lost power overnight. In Kyiv, residents huddled in metro stations as temperatures dropped below zero.

Both sides returned to the table. Both called the discussions "constructive."

This pattern-bombing between bargaining sessions-is not diplomatic miscalculation. It is the diplomatic strategy. For Moscow, peace talks have never been a path to peace. They are another front in the war.

GLOBSEC's Iuliia Osmolovska, a former Ukrainian diplomat, told Euromaidan Press that what the West sees as failed diplomacy is actually "a mixture of old KGB methods and the Gromyko school." Here's how that school developed-and why the West keeps falling for it.

Who was Andrei Gromyko?

Western analysts reaching for precedents often land on Andrei Gromyko. He served as Soviet foreign minister from 1957 to 1985-the longest tenure in Soviet history.

Gromyko negotiated with six US presidents, from Eisenhower to Reagan. He sat across the table during the Cuban Missile Crisis, the SALT arms talks, and virtually every Cold War flashpoint.

US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger recalled him as "highly intelligent, always prepared, never lost his composure." He added: "If you can face Gromyko for one hour and survive, then you can begin to call yourself a diplomat."

The West called Gromyko "Mr. No" for good reason-he refused nearly every proposal fielded by rival negotiators.

The Gromyko Method

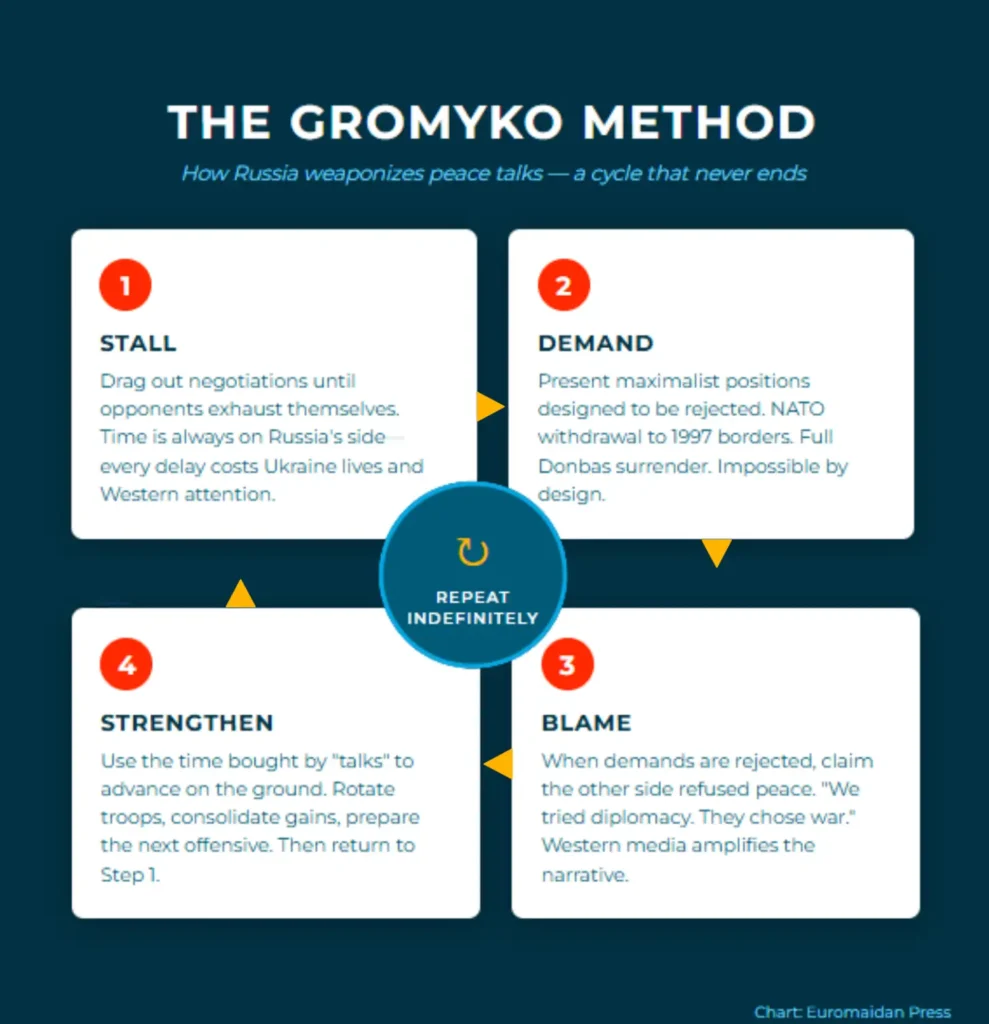

Such tenacity defines the Gromyko Method, which boils down to four tactics:

- Stall until opponents exhaust themselves

- Demand maximalist positions you know will be rejected

- Blame the other side for the impasse

- Use the time to strengthen your position on the ground

Former Ukrainian military chief Valerii Zaluzhnyi warned that this is exactly what the West mistakes for peace talks today-Soviet-era psychological warfare dressed in diplomatic language:

"Drawn-out talks on 'ending the war' create an illusion that Russia genuinely seeks peace, while in reality, they give Moscow time to kill as many Ukrainians as possible during the talks and rearm for the next stage of aggression."

From Gromyko to KGB: How the method evolved

But Gromyko is only one element. As Osmolovska explains:

"If you look at how Soviet diplomatic school developed and transformed into modern Russian diplomacy, it's still a mixture of old KGB methods and the Gromyko school. Russians don't undervalue psychological factors. They use many tricks exploiting psychological vulnerabilities. Underestimating this component makes Western partners very vulnerable."

The KGB contribution-what scholars call "active measures"-adds layers of deception, disinformation, and psychological manipulation to the already grueling Gromyko-style marathon.

Modern Russian diplomacy doesn't just stall. It destabilizes, divides, and disorients.

The current approach is also shaped by Russia's siloviki culture-the dominance of people with military and security backgrounds in Putin's inner circle. This frames negotiations not as problem-solving but as an extension of conflict.

Three strategies Russia deploys

Osmolovska identifies three core strategies from conflict theory that Russia uses at the negotiating table-all treating diplomacy as warfare by other means:

1. Competition

Zero-sum framing is essential. "It matters not just how much I win, but also how much the other side loses," Osmolovska explains. This means any Ukrainian gain is a Russian loss-and vice versa. Compromise becomes impossible when the goal is domination, not resolution.

2. Avoidance

Osmolovska puts it bluntly: "No body, no crime-meaning no person at the negotiation table, and if something depends on this person, negotiations get stalled."

During the Normandy format talks, then-Foreign Minister Pavlo Klimkin tried repeatedly to reach Lavrov-failed many times. President Poroshenko tried to reach Putin-failed many times. Russians simply stopped showing up.

The process froze not because talks failed, but because Russia refused to allow them to proceed.

3. Revenge with self-damage

Western conflict theorists consider this the most "dehumanitarian" strategy-accepting costs to oneself in order to punish the opponent. Most negotiation schools barely discuss it.

"This is exactly what Russians are playing in Ukraine," Osmolovska notes. "They're trying to punish Ukraine, but as a result, they also incur costs they're ready to tolerate."

Why tolerate the losses? Because for Russia, non-linear, non-mathematical calculations matter more than material costs. These are intangibles-pride, respect, being feared-that can't be measured by cost-benefit analysis.

Why Western cost-benefit analysis fails

This is where Western understanding consistently breaks down. American and European negotiators, steeped in rational-choice theory, assume their counterparts want to maximize measurable gains and minimize measurable costs. If you offer a good enough deal, the thinking goes, a rational actor will take it.

Trending Now

Russia doesn't work that way.

"Western mentality is mostly grounded in the theory of rational choice," Osmolovska says. "But Russian mentality, according to Western view, appears irrational. Russians tend to value intangibles-pride, respect out of fear, being feared-much more than direct cost-benefit analysis."

"When Russians think the whole world is scared of them, fear leads to respect automatically in Russian culture. There's a proverb: 'If he fears, then he respects me. If he fears, then he loves me.' This is exactly how Russians think." -Iuliia Osmolovska

The Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) put it bluntly in a 2024 report: "The Kremlin sees democratic values as the greatest security threat and the West as an existential, systemic enemy. The logic of a zero-sum game excludes negotiations understood as a path to compromise, while violence is seen as a natural part of diplomacy."

This explains why sanctions that should rationally constrain Russian behavior often fail to do so. Moscow is willing to absorb enormous economic and human costs-including 35,000 casualties per month during its 2025 offensive operations-because suffering demonstrates strength, and strength commands the respect that Russia craves.

The pattern across post-Soviet conflicts

This isn't Ukraine-specific. The pattern is visible across post-Soviet conflicts.

In Georgia, Moscow spent years in "peace talks" over South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Meanwhile, it armed separatists, issued Russian passports to locals, and positioned forces for the five-day war of August 2008.

In Moldova, the Transnistria "peace process" has ground on for more than three decades. During that time, Russia has maintained troops on Moldovan territory, created a smuggling corridor, and used the frozen conflict as leverage against Chișinău's European aspirations.

In Syria, Russia participated in countless UN-brokered peace initiatives from 2015 onward while its aircraft systematically bombed hospitals, markets, and residential areas. According to Amnesty International, Russian and Syrian forces "deliberately and systematically" targeted medical facilities as part of a military strategy. The diplomatic track provided cover; the military track delivered results.

Diplomacy as hybrid warfare

Russia's weaponization of negotiations fits within a broader doctrine of hybrid warfare-the integration of military force, economic coercion, information operations, and diplomatic maneuvering into a single strategic campaign. Talks are never isolated from the battlefield; they are an extension of it.

The December 2021 ultimatums illustrate this perfectly. Weeks before the full-scale invasion, Moscow demanded NATO withdraw to its 1997 borders, remove troops from Eastern Europe, and submit new proposals on strategic stability. As the Brookings Institution noted, the demands were "knowingly presenting unrealistic demands" designed to be rejected-classic "high anchoring." The Atlantic Council reported that talks reached a "dead end" when both sides recognized there was "little room for compromise."

"Russians were well aware they wouldn't fly," Osmolovska notes. "It was just a pretext for the full-scale invasion. They said: 'If you are not considering this, then we are going to act unilaterally, militarily.'"

The Minsk trap

The Minsk agreements of 2014-2015 remain the clearest example of Russia's diplomatic warfare against Ukraine. Sold to Western audiences as a path to peace, they were designed from the start as a trap.

Leaked Kremlin emails from Vladislav Surkov, Putin's advisor, revealed Moscow's true intent: use the agreements to legitimize its proxy "republics," force constitutional changes that would give Russia veto power over Ukrainian foreign policy, and buy time to prepare for a larger war.

The West, desperate for stability, enforced Minsk's terms on Kyiv while ignoring Russia's violations. As analysts at the European Council on Foreign Relations noted, between 2014 and 2022 there were 29 ceasefires, each agreed to remain in force indefinitely-yet none lasted more than two weeks.

The historical record is unambiguous. Between 2014 and 2022, Ukraine participated in more than 200 rounds of negotiations with Russia in various formats, alongside 20 attempts at ceasefires. None produced lasting peace. Each pause allowed Russia to consolidate gains, rotate troops, and prepare for the next escalation.

The full-scale invasion of February 2022 was not a failure of diplomacy-it was, from Moscow's perspective, the culmination of eight years of diplomatic success.

Abu Dhabi: The pattern repeats

The same dynamic is emerging at Abu Dhabi. Before talks began, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov demanded Ukraine surrender the entire Donbas-including roughly 5,000 square kilometers Russian forces have failed to capture in nearly four years of full-scale war. The demand is impossible by design. When Ukraine refuses, Russia claims it tried diplomacy. When the West pressures Ukraine to negotiate anyway, Russia gains time to continue killing.

The composition of the delegations tells you what kind of talks these are.

Russia replaced Vladimir Medinsky-a cultural minister known for ideological lectures-with Admiral Igor Kostyukov, head of the GRU. Kostyukov is no ordinary negotiator. He earned the title Hero of Russia for intelligence operations in Syria, where the GRU refined the tactics of talking peace while waging war. He is under US, EU, and UK sanctions.

His assessment of Abu Dhabi to Russian state television was cryptic: "Everybody said that it was constructive. Everyone understands everything."

Ukraine countered with Kyrylo Budanov, former head of military intelligence (HUR), now Zelenskyy's Chief of Staff. A graduate of Odesa Military Academy who served in CIA-trained special forces, he has maintained direct channels with his Russian counterparts since March 2022-initially just to coordinate prisoner exchanges.

Ukrainian analyst Volodymyr Fesenko noted that Kostyukov's appointment is "a status- and function-based adjustment to Budanov." Volodymyr Tryukhan observed that Budanov's understanding of the adversary "from the inside" deprives Russia of room for bluffing. Moreover, Budanov's presence "quite literally triggers Russian propaganda."

You send diplomats to debate. You send your spymaster to dictate. That Moscow chose Kostyukov tells you which phase the Kremlin thinks it's in.

The cost of misunderstanding

The West's failure to grasp Russian negotiating psychology carries real consequences.

Ukraine cannot negotiate away Russia's imperial ambitions. No clever formula will satisfy a negotiating partner who views fear as the foundation of respect and suffering as proof of strength. The Kremlin does not want a deal; it wants victory. And as long as the West keeps searching for rational actors in a room full of ghosts from the Soviet past, Moscow will keep using the negotiating table as just another weapon in its arsenal.

Read also

-

She spent 15 years decoding Russian talks. Her verdict: the battlefield will decide.

-

Russia’s last “Ukraine peace deal” led to Europe’s biggest war since WWII. Here’s why this one could be worse.

-

9 reasons negotiations with Russia are utterly pointless

-

Everything you wanted to know about the Minsk peace deal, but were afraid to ask