The floating oil glut marks a turning point for sanctions enforcement. Russia can still pump crude and load tankers, but every barrel trapped at sea delays revenue funding Russia’s war effort.

Buyers representing more than 95% of Moscow’s seaborne exports now calculate that purchasing from sanctioned Rosneft and Lukoil risks secondary penalties—creating the kind of cash-flow pressure analysts warned could test Moscow’s ability to sustain military operations.

US sanctions trigger steep shipment drop

Russia’s seaborne crude shipments crashed to 3.58 million barrels per day in the four weeks ending 2 November, down 190,000 barrels from the previous period—the sharpest decline since January 2024, according to vessel-tracking data compiled by Bloomberg.

The collapse followed the 22 October US sanctions targeting Rosneft and Lukoil, Russia’s two largest oil exporters. Together, they account for roughly half of the country’s 10.6 million barrels per day output and nearly a third of federal tax revenue.

However, the crisis emerged in delivery—Russia loads tankers but can’t unload them.

Russian exporters continued filling tankers at port terminals, yet refiners in India, China, and Türkiye—buyers representing more than 95% of Moscow’s seaborne crude exports—increasingly refused to accept deliveries. The result: 380 million barrels are now floating at sea, up 27 million barrels or 8% since early September, Bloomberg reported.

At current prices near $60 per barrel, that floating inventory represents approximately $1.6 billion in crude that cannot generate immediate revenue for Russia’s war machine.

Chinese state firms cancel orders

The most significant buyer retreat came from China, long considered Moscow’s economic safety net after Western sanctions redirected Russian oil trade from Europe to Asia.

State-owned giants Sinopec and PetroChina stayed on the sidelines after the US sanctioned Rosneft and Lukoil in October, canceling some Russian cargoes, Bloomberg reported on 3 November. Smaller private refiners also held off purchases, fearful of attracting penalties similar to those faced by Shandong Yulong Petrochemical, which the UK and EU recently blacklisted.

China’s Yulong refinery lifts Russian crude imports to 400,000 barrels a day after EU, UK sanctions

Rystad Energy estimates the buyer pullback affects approximately 400,000 barrels per day—nearly 45% of China’s total seaborne oil imports from Russia.

Russian crude prices to Asia plunged as refiners turned away cargoes.

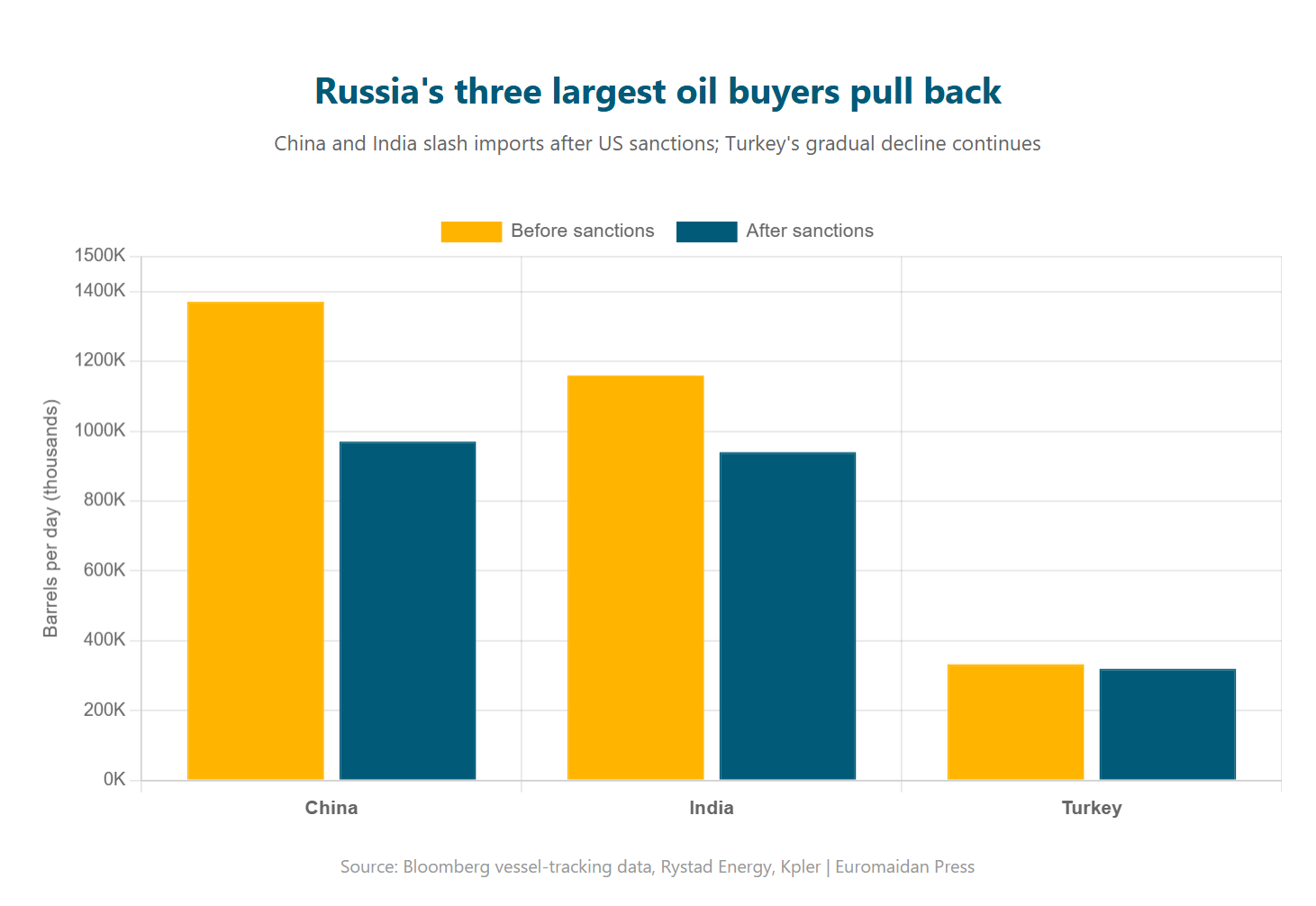

Shipments to Chinese ports fell to 970,000 barrels per day in the four weeks to 2 November, while deliveries showing no final destination surged to more than 1.3 million barrels per day—oil loaded onto tankers but with buyers yet to materialize.

India, which had absorbed nearly 1 million barrels per day of Russian crude, saw deliveries drop from 1.16 million to 940,000 barrels per day. Indian state-run refiners paused purchases, calculating whether they could continue sourcing from smaller suppliers rather than sanctioned Russian energy giants while avoiding secondary sanctions exposure.

Türkiye, Russia’s third-largest buyer, cut purchases to approximately 320,000 barrels per day as refiners sought alternative supplies from Iraq, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and Kazakhstan.

Oil revenue plunges

Buyer after buyer abandoned Russian cargoes. Bloomberg reported that the gross value of Moscow’s crude exports fell by approximately $90 million weekly to $1.36 billion in the 28 days ending 2 November, with both export quantities and prices declining.

In the week ending 2 November, export values averaged about $1.15 billion in the seven days ending 2 November—down 27% from the previous week.

The revenue squeeze comes as Russia faces mounting economic strain across multiple fronts. The country’s budget deficit hit 4.2 trillion rubles ($48.2 billion) in the first eight months of 2025—four times higher than the previous year, according to analysis by Ukrainian economist Volodymyr Vlasiuk.

With real inflation around 25-26% rather than the official 8.2%, and civilian sectors declining, the Kremlin faces what Vlasiuk described as classic stagflation—stalling growth with accelerating prices.

Trending Now

Combined with Ukrainian drone strikes that have reduced Russia’s refining output by up to 90% at targeted facilities, the sanctions-driven revenue loss creates a double squeeze on Moscow’s war funding.

Floating storage reveals sanctions working

The 380 million barrels trapped at sea represent more than delayed revenue—they reveal how sanctions work through incremental strangulation rather than immediate blockade. Russian oil companies can still pump crude and load tankers, but cannot convert that crude into usable war revenue without buyers willing to risk secondary sanctions.

Moscow cannot easily redirect these floating cargoes.

More than 1.2 million barrels per day sit on ships showing destinations as Port Said or the Suez Canal, or vessels from Pacific ports with no clear delivery point. Another 140,000 barrels per day float on tankers yet to signal any destination whatsoever.

Torbjörn Törnqvist, CEO of the commodities trading company Gunvor Group, told Bloomberg the disruption may prove temporary, predicting “more and more of the disrupted Russian oil, one way or another, finds its way to the market.”

But the simultaneous pullback by India, China, and Türkiye eliminates Russia’s ability to compensate through market diversification.

Together, these three buyers represented more than 95% of Moscow’s seaborne crude exports—and there is no fourth market capable of absorbing equivalent volumes.

As one tanker after another joins the floating inventory, unable to deliver cargoes, Russia faces an impossible choice: continue loading crude that generates no immediate revenue while paying storage costs and ship rentals, or cut production and accept permanent market share loss.

Either option accelerates the economic timeline analysts identified months ago.

The floating blockade, invisible to most observers but precisely measured by vessel-tracking systems, may prove the clearest indicator of when economic pressure on Russia’s war machine reaches unsustainable levels.