On Easter Monday, 21 April 2025, Pope Francis died at 88, leaving behind a complex legacy on Russia's war against Ukraine. For Ukrainian Orthodox theologian Father Cyril Hovorun, Francis embodied a fundamental tension: "He was on the right side of history. He was pro-Ukrainian, undoubtedly – even though he was not explicitly pro-Ukraine always in the way that we want him to be."

This paradox defined Francis's approach to Ukraine – a pontiff who genuinely empathized with Ukrainian suffering yet remained constrained by Vatican diplomatic traditions that prevented him from explicitly naming Russia as the aggressor and calling evil by its name.

The Secret Santa pope

In December 2023, as Ukrainian soldiers from the 93rd "Cold Yar" Brigade struggled to fund reconnaissance drones for their operations against Russian forces, a mysterious donation appeared. Ukrainian historian Oleksandr Zinchenko, who was coordinating the fundraiser, received a call from a trusted intermediary with an unexpected offer: a "Secret Santa" wanted to ensure the soldiers would have their drones.

"Maybe we can buy a third backup drone?" the intermediary suggested after learning the fundraiser was nearly complete. The third drone was eventually nicknamed "Santa" to maintain the donor's anonymity.

Only after Pope Francis's death did Zinchenko reveal the shocking truth: the "Secret Santa" was none other than Pope Francis himself. The donation came from the pontiff's personal funds—not Vatican coffers—and was made with a strict requirement of confidentiality.

This clandestine support for Ukraine's defense forces stands in stark contrast to the same Pope who, just months later in March 2024, would controversially suggest Ukraine should have "the courage to raise the white flag" and negotiate with Russia—a statement that provoked outrage across Ukraine and beyond.

These two acts—secretly funding military equipment while publicly calling for negotiations that many Ukrainians viewed as surrender—encapsulate the profound contradictions that defined Pope Francis's approach to Russia's war against Ukraine.

A slow evolution toward clarity

Despite all the contradictions, Pope Francis's position on Russia's war against Ukraine did eventually gravitate more towards solidarity with the victim – albeit too slowly and incompletely for many Ukrainians. Before the full-scale invasion, Francis warned that war would be "madness" and called for dialogue between Kyiv and Moscow, but avoided assigning responsibility for escalating tensions.

In the immediate aftermath of the 24 February 2022 invasion, his comments remained notably vague. While expressing concern for suffering Ukrainians, Francis avoided naming Russia as the aggressor for several months. In May 2022, he suggested that "NATO's barking at Russia's door" may have provoked Putin – a statement that mirrored Kremlin talking points and deeply offended Ukrainians.

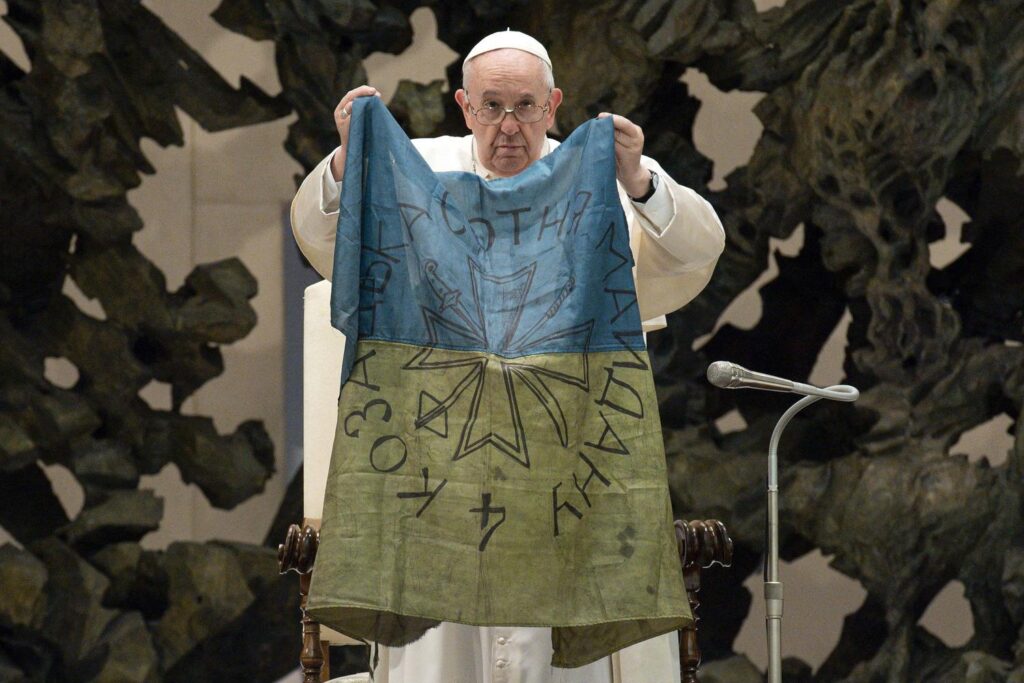

The Pope's first significant gesture of solidarity came in April 2022, when he unfurled a Ukrainian flag from Bucha and spoke of "the martyred city" after Russian atrocities were uncovered there. "The recent news from the war in Ukraine, instead of bringing relief and hope, brought new atrocities," he said, though still without directly naming Russia.

By late 2022, Francis began showing more willingness to assign responsibility. In an interview with America magazine in November, he finally stated: "Generally, the cruelest are perhaps those who are of Russia but are not of the Russian tradition, such as the Chechens, the Buryats and so on."

While this comment itself proved controversial for singling out Russia's ethnic minorities rather than Russian leadership, it marked his first explicit acknowledgment of Russia as the aggressor.

The strongest condemnation came in January 2023, when Francis he descibed the conflict as "a crime against God and humanity" in an annual address to diplomats. On the second anniversary of the invasion, he directly called out Russia's "cruel, absurd" war in Ukraine, abandoning his previous pattern of describing it merely as a "war in Ukraine."

Yet these steps toward clarity were repeatedly undermined by mixed messages.

In August 2023, he told Russian youth they were heirs to "great Russia" and its imperial traditions. In March 2024 came the controversial "white flag" comments suggesting Ukraine should capitulate.

This halting evolution – too little, too late for many Ukrainians – illustrates Francis's struggle to reconcile his personal empathy with centuries of Vatican diplomatic tradition that hesitates to directly name aggressors.

"Unevangelical" diplomacy

"On one hand, Pope Francis clearly solidarized himself with the Ukrainian people and their suffering. He was one of the few religious leaders globally who have been outspoken about the war, who has been clear about who is the victim," explains Hovorun in an interview following the Pope's death. "At the same time, he was not as clear about who was the aggressor, and that is one of the things that Ukrainians don't like about him."

This diplomatic ambiguity frustrated Ukrainians who expected the Church's moral authority to name evil clearly. Hovorun traces these contradictions to entrenched Vatican diplomatic traditions, which holds that even the worst aggressors are not named.

"The Holy See can condemn acts of violence, acts of violation of human rights, of human life. At the same time, they hesitate to name the perpetrator," he explains the Vatican's failure to confront evil.

"I personally believe this tradition is ambiguous tradition, to say the least. It is unevangelical, unchristian, and unprophetic."

This approach took shape during the Cold War, when the Vatican sought dialogue with the Soviet Union even during severe religious persecutions. It extended back further, to the 1930s, when "the Holy See tried to develop good relationships with the Soviet Union, even in the period of the worst persecutions against the Church," Hovorun points out.

"We know from the Old Testament that prophets not just stood with victims – they also explicitly condemned perpetrators," he argues. "In this sense, Vatican diplomacy is not prophetic at all, and the late Pope concurred with this line of Vatican diplomacy."

Yet Francis occasionally broke from this tradition in striking ways. When he dismissively labeled Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill as "Putin's altar boy" during an interview, the remark sent shockwaves through Moscow and beyond.

"This phrase has probably become a sort of label that will stay with Patriarch Kirill after his death for a long time, if not for centuries," Hovorun observes with a hint of satisfaction. "That's why I've seen words of condolences coming from President Putin, but I haven't seen the words of condolences coming from Patriarch Kirill yet."

Pope Francis was “pro-Ukrainian” but wouldn’t name Russia as aggressor: Orthodox theologian explains pontiff’s complex legacy

The burden of history

The marble halls of the Vatican carry the echoes of past moral failures.

During World War II, the Holy See maintained diplomatic silence on the Holocaust despite having knowledge of Nazi atrocities. The Church's concordat with Mussolini's fascist regime and support for right-wing dictatorships in countries like Croatia and Hungary stain its historical record.

"We now know from the documents that have been made public that the Vatican was pretty much aware about the Holocaust and all the atrocities by the Nazis, and yet they kept silent when they could speak," Hovorun explains.

Even Francis himself faced questions about his role during Argentina's "dirty war" under the Perón dictatorship. "Pope Francis was active in Argentina at that time, and that is one of kind of blind spots in his biography," notes Hovorun.

Yet as Pope, Francis took unprecedented steps to acknowledge past Church failures. "Under his pontificate, the Church really went through some kind of catharsis, some kind of repentance," Hovorun acknowledges. "He publicly apologized for the participation of the Catholic Church in the Rwandan genocide. He did it explicitly, and he should be credited for that."

This willingness to acknowledge historical failings set an important example that Hovorun hopes other churches, particularly the Russian Orthodox Church, will eventually follow. "Pope Francis has set a very good example for the future church leaders how to acknowledge the mistakes of their own churches."

Hi! My name is Alya Shandra, I'm the author of this piece. I believe in the power of data and analysis, and that's why we try to give you the best of it at Euromaidan Press.

Become our patron to help us bring you the best insights from Ukrainian and foreign analysts so we can cut through the noise together.

Words that wounded

For Ukrainians, Francis's verbal missteps often overshadowed his humanitarian efforts. When he referred to Daria Dugina, daughter of ultranationalist Alexander Dugin and herself a propagandist of the "Russian World" ideology, as an "innocent" victim of war in August 2022, Ukrainian officials were outraged.

Catholic theologian Regina Elsner identified fundamental issues undermining Francis's approach: the Vatican's lack of expertise on Eastern Europe beyond Russia, its strategic alliance with Moscow against "liberalism," and its ignorance of how Russian propaganda weaponizes neutrality.

Trending Now

"When the Vatican agrees to give the West a share of guilt and Russia a share of truth, it exactly contributes to these myths, it admits that it has no idea about the situation in Ukraine and is not able to differentiate information," Elsner wrote.

The Pope's suggestion that Ukraine should have the "courage" to raise the "white flag" in March 2024 further inflamed tensions. Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba responded bluntly: "Our flag is blue and yellow. This is the flag we live with, this is the flag we die with, and we will not raise any other flags."

Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, walking a delicate line of respecting the Pope while defending his people, pushed back: "Surrender is not on the minds of Ukrainians," he stated, describing cities like Kharkiv and Zaporizhzhia where civilians endure daily Russian bombardments yet refuse to yield.

The man behind the miter

Two foundational elements of Pope Francis’s worldview shaped his conflicted response to Russia’s war on Ukraine — both rooted in the theology of liberation that emerged from Latin America in the 20th century.

First, Francis absorbed a deep suspicion of geopolitical power from the liberationist tradition. Shaped by Argentina’s history of dictatorship, foreign interference, and elite complicity, liberation theology taught that no superpower — East or West — can claim moral high ground while oppressing the vulnerable while viewing conflict through the lens of structural violence and historical injustice.

For Francis, this translated into viewing the Russia-Ukraine war through a lens where no major power could claim moral purity. His controversial comment about "NATO barking at Russia's door" echoed a liberationalist impulse to view western geopolitical alliances with suspicion -- a perspective that made sense in Latin America's history but proved catastrophically inadequate for Ukraine's reality as a victim of unprovoked Russian aggression.

When faced with clear imperial aggression requiring prophetic naming of evil, Francis's liberation theology background left him struggling to abandon its both-sides framing.

Second, Francis’s pacifism was not generic idealism — it flowed from a theological commitment to nonviolence as the heart of Christian witness, a central tenet in many forms of liberation theology.

For Francis, peace is not merely the absence of war, but the fruit of justice, mercy, and mutual listening. His repeated calls for negotiation, even under fire, reflect a belief that war — even in self-defense — always represents a defeat of human dignity. He saw the suffering of Ukrainians, mourned with them, and secretly acted to help — but remained reluctant to endorse armed resistance in moral terms.

Additionally, the Vatican's historical gravitation towards diplomacy played a role. As noted by Le Monde, "The Pope's ambiguity reflected the Vatican's desire to maintain its role as a potential mediator in global conflicts." By avoiding explicitly condemning Russia, Francis was preserving diplomatic channels that could theoretically be used for peace negotiations.

Some analysts suggest Francis was cautious about damaging relations with the Russian Orthodox Church, which he had been trying to improve since his historic meeting with Patriarch Kirill in 2016. This interfaith diplomacy potentially influenced his hesitancy to directly condemn Russia, creating what critics called a "strategic ambiguity" that ultimately failed both Ukraine and the cause of peace.

Hovorun believes Francis's approach stemmed from genuine concern hampered by inherent limitations. "I believe he was profoundly empathetic to the Ukrainians, and most of his statements were driven by this empathy," he says. "At the same time, empathy has its limits. When you don't suffer yourself, you feel you can understand what others suffer – it's different from when you suffer yourself."

Humanitarian action behind the scenes

Despite all the contradictions, this concern shone through the Pope's genuine openness to hearing Ukrainian perspectives and his active work in practical humanitarian help to Ukraine.

In 2015, just one year after Russia's initial invasion of eastern Ukraine, Francis launched the "Pope for Ukraine" humanitarian initiative, raising 17 million euros for frontline populations. As Archbishop Borys Gudziak later revealed, this campaign began during a meeting with Ukrainian Catholic bishops when he told Francis three simple things: "They need help. We can help. We will help." The Pope immediately wrote down these words and acted within a week.

The Vatican's help for Ukraine intensified in 2022, with Cardinal Cherni coordinating assistance to Ukrainian refugees. The Pope supported Ukrainian demands of opening humanitarian corridors to Russian-occupied cities, particularly Mariupol. He pressured world leaders to restore the export of Ukrainian grain through Black Sea ports blockaded by Russia, appealing to not use hunger as a weapon.

He rebuked Putin's threats of using nuclear weapons in 2022 as "madness" and facilitated prisoner exchanges. Ukrainian intelligence chief Kyrylo Budanov confirmed in 2022 that they had "appealed to the Vatican for help in freeing our people," with Francis personally involved in these negotiations.

In 2023, the Vatican announced a "secret mission for peace" in Ukraine, spearheaded by Cardinal Mateo Zuppi, who undertook several visits to Kyiv and Moscow. These activities, apparently, resulted in the return of several Ukrainian children kidnapped to Russia in 2023, pointing to the Vatican's role as a neutral intermediator in humanitarian issues where direct contact between Moscow and Kyiv was impossible.

"The Holy Father spoke about the war in Ukraine nearly 400 times. Almost every week—on Wednesdays, and Sundays—he called for peace, summoning the world to pray for Ukraine as he did again just yesterday in his last Urbi et Orbi. He always remembered the 'tortured people of Ukraine,'" Gudziak recalls.

The Pope sent Cardinal Konrad Krajewski on dangerous humanitarian missions directly to Ukraine's frontlines. On one trip, the Cardinal's vehicle came under fire as he delivered generators, medical supplies, and other aid to besieged areas. Francis repeatedly met with Ukrainian refugees, prayed with them, and maintained ongoing communication with Ukrainian religious leaders.

The reformer within limits

Beyond Ukraine, Hovorun credits Francis with significant reforms within the Church, particularly in advancing synodality – an Eastern Christian concept emphasizing collective decision-making.

"Pope Francis really enhanced what we call synodality in the Church," Hovorun explains. "Even though he didn't have to do so – he was the Pope, he could rule the church unilaterally without consulting anyone – at the same time, he preferred to consult different ecclesial bodies."

This reform represents Francis's most ambitious legacy project. In 2021-2024, he launched a global "Synod on Synodality," a three-year process of consultations involving bishops, clergy, and lay Catholics worldwide. The initiative sought to fundamentally transform Church governance by creating permanent structures for dialogue and shared decision-making across all levels of Catholic life.

"He tried to humanize this machinery, to reform it," Hovorun acknowledges. "To some extent he succeeded in reforming the central administration of the Catholic Church, the Roman Curia. He changed, I would say, both the form and the content of the central administration."

These reforms demonstrate his willingness to challenge entrenched power structures within the Church. Yet when it came to diplomatic protocol regarding Russia's war, Francis could never fully break from tradition – leaving his legacy on Ukraine defined more by what he didn't say than what he did.

A divided legacy

Pope Francis leaves behind a legacy as divided as his own approach to Ukraine – a pontiff who secretly funded military drones while publicly suggesting Ukraine negotiate with Russia; a reformer who pushed for greater synodality within the Church while failing to break from outdated diplomatic traditions.

His pontificate illustrates both the power of empathy and its profound limitations in the face of aggression that demands unambiguous moral clarity and the prophetic courage to name evil.

Ultimately, Francis’s approach revealed both the strengths and limitations of liberation theology on the world stage. Its commitment to the poor and its critique of empire made him attentive to suffering — but its mistrust of power and hesitance to moralize conflict left him struggling to name evil when clarity mattered most.

In trying to be a shepherd of peace, Francis sometimes became a stranger to justice - and was neither the prophet that the Ukrainians hoped for, nor the diplomat that the Vatican tradition expected.