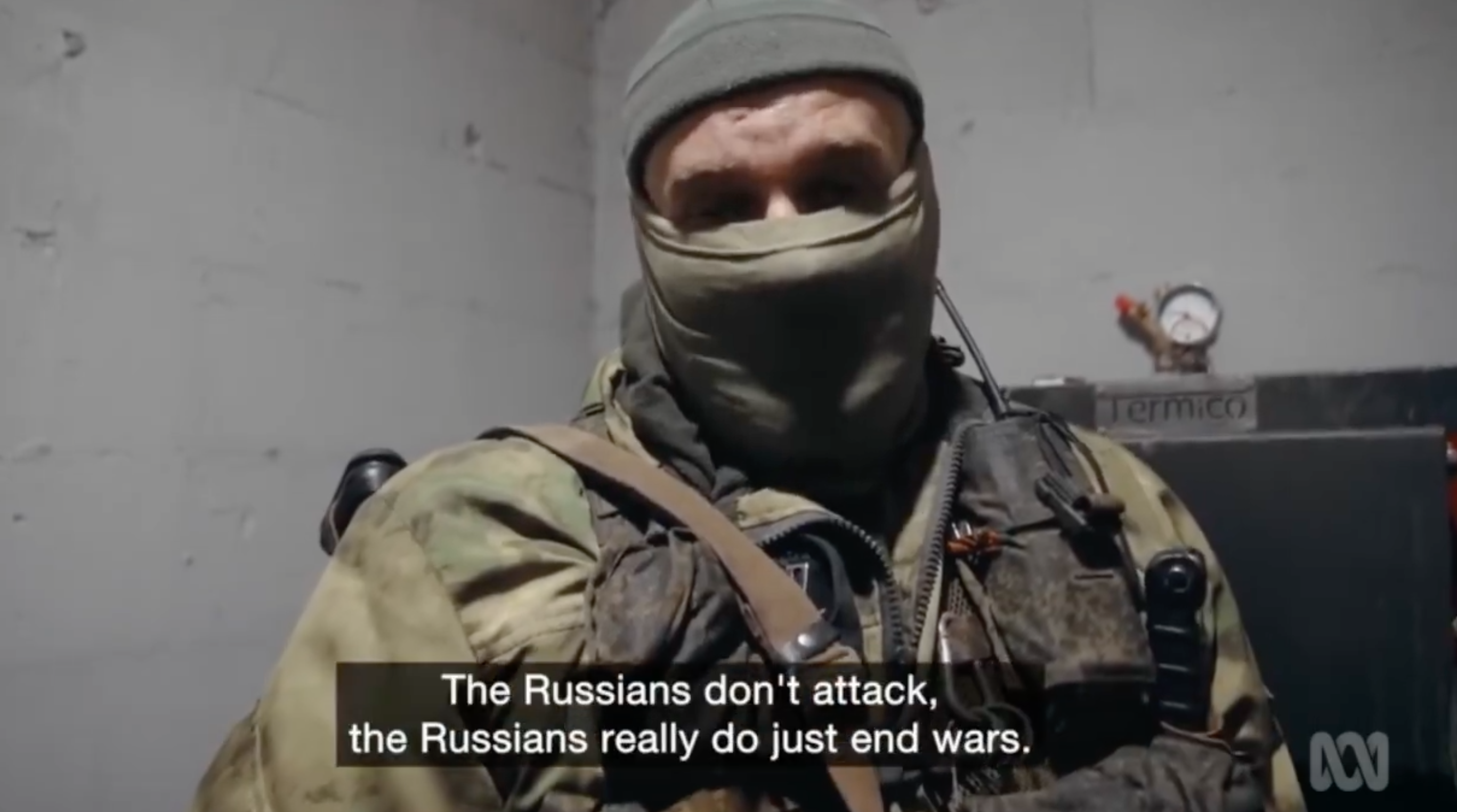

“The Russians don’t attack, the Russians end wars.”

A fully-equipped Russian man, standing and smoking a cigarette, is seen saying that in front of the camera. You can’t see his face, as he’s wearing a balaclava. But you can hear his tone and almost see the smirk that such tone is almost always accompanied with.

This could be a scene from Kremlin-funded propaganda that features ardent putinists like Russian singer Nikolay Baskov, who used exactly the same line on Russians “ending wars” in February 2022 as Moscow launched its full-scale onslaught.

Only it’s not.

This is the latest in the series of Western attempts to humanize the “inhumanizable”: Russian soldiers who came to Ukrainian soil to conquer land and subjugate the population – whether with pointed sticks or very pointed sticks.

This time, however, it is not produced by former RT employee and Russian émigré to Canada Anastasia Trofimova, but by British documentary-maker Sean Langan.

Dubbed “Ukraine’s War: The Other Side,” it was first aired in March 2024. The Guardian described it as an “intriguing but curious documentary” and Ukraine’s Ambassador to Australia Vasyl Myroshnychenko as a “journalistic equivalent of a bowl of vomit.”

Despite the initial criticism, the documentary still made it to larger audiences and was shown on multiple platforms, with the Russian BBC’s office recently uploading it to their YouTube channel and reigniting the debate of finding moral equivalence between the victim and the aggressor.

Flirting with the enemy

Like most documentary makers, Langan is both the interviewer and the narrator in this production.

The premise is simple. He interviews Russian soldiers to understand what they make of the war they launched in another country as part of his “unseen and indispensable perspective on Russia's war against Ukraine.” For this reason, we will not deep-dive into every aspect of this documentary, as it cannot, by default, contain any answers of real value, and we cannot sympathize with the plight of people who suffer from their own evil doings.

Nonetheless, some scenes from this movie are notable due to the visual messaging that were not as evident in the “Russians at war” documentary.

In the course of it, Langan, who is much more willing to appear in scenes compared to Trofimova but likewise doesn't really explain who allowed him to get to the front in Donetsk Oblast to film this movie, uses all sorts of techniques to merge with his interviewees. Like smoking on camera, a largely bygone and unwelcome occurrence on TV, different lighting to project the mood and create an atmosphere and contrasts.

Take the scene with the Russian soldier who was in his own words in “Buchaand Irpin.” Langan asks him about the Russian massacre there, to which the soldier answers in the typical Russian manner.

First, that they “were told to withdraw and left”, averting any responsibility for being there in principle. Second, “everything was left intact there,” though the word intact is an incorrect translation as he used the word “kulturno” (cultural), which can have any meaning you want in this context as it’s used as slang to describe something that you deem to be “solid/appropriate/etc”. Third, that he “found out” about what happened online.

Trending Now

To Langan’s credit, he did note that the crimes were documented, but this also begs the question of which answer he wanted to elicit from the aggressor's soldier.

In this atmosphere, you see the typical cold hues that give you the sense of the mundaneness and darkness of the war: he “doesn’t know”, he “wasn’t there”, it’s “just war”, and anyway, now isn’t the right place to discuss war crimes, as per Langan’s own admission.

But the lighting contrast dramatically changes in the scene where the Russian soldiers are sitting around the fire, talking about their lives and showing to the camera, in an act most cynical, photos of their families, adding that though it is hard, the circumstance that ultimately keeps them going in their war of aggression is their loved ones. Much warmer hues are added to enhance the visual message of that scene placing the viewer inside a warm atmosphere of people bound by their joint goal of killing Ukrainians.

The demand for the other side

“Ukraine’s War: The Other Side”’s premise is no different from that of “Russians at war,” an attempt to show that Russian soldiers are ordinary people with their own opinions, families, happiness, and grief. They laugh, they cry, they question, they boast, they smile, they ponder – and they kill. Only the latter isn’t the leitmotif of the movie but an unfortunate byproduct hidden in the narrative.

There’s no single or clear-cut answer as to why Western audiences want a better understanding of people who come to another land to kill. Is it a study of human nature? An attempt to question the dominant narrative? Plain foolishness?

While those questions remain rhetorical, it is also noticeable that the general demand for Russian input has grown in the West.

And not only documentaries are concerned.

Take “Anora,” a Hollywood hit movie about a young Russian oligarch in the US who gets married to a stripper. Following its success, Hollywood welcomed two new Russian stars: Mark Eidelshtein and Yuriy Borisov.

Or HBO’s hit series “The White Lotus,” which features Russian actor Yuriy Kolokolnikov, who replaced Milos Bikovic, an openly Putin-loving Serbian actor, following a major public backlash.

Despite these actors being undoubtedly talented, none of them publicly spoke out against Russia’s war on Ukraine, with Borisov and Kolokolnikov visiting the Russian-occupied Crimea and Borisov participating in Russian propagandistic movies.

All of them likewise live and work in Russia, where the majority of people support the war against Ukraine, making the West’s quest for “good Russians” an eternal undertaking.