The cessation of Russian gas transit through Ukraine and Europe's gradual weaning off Russian supplies mark a truly historic moment. We're witnessing the end of an era—Europe's long-standing energy dependence on Russia is finally drawing to a close.

A legacy of dependency

The Soviet gas flow to Europe began in the late 1960s, with initial pipelines reaching Czechoslovakia and Austria. When West Germany signed its first gas deal in 1970, few could have predicted the scale of future dependency. The 1973 global oil crisis, triggered by the assertiveness of Middle Eastern monarchies, only accelerated Europe's quest for diverse energy sources - ironically pushing it further into Soviet arms.

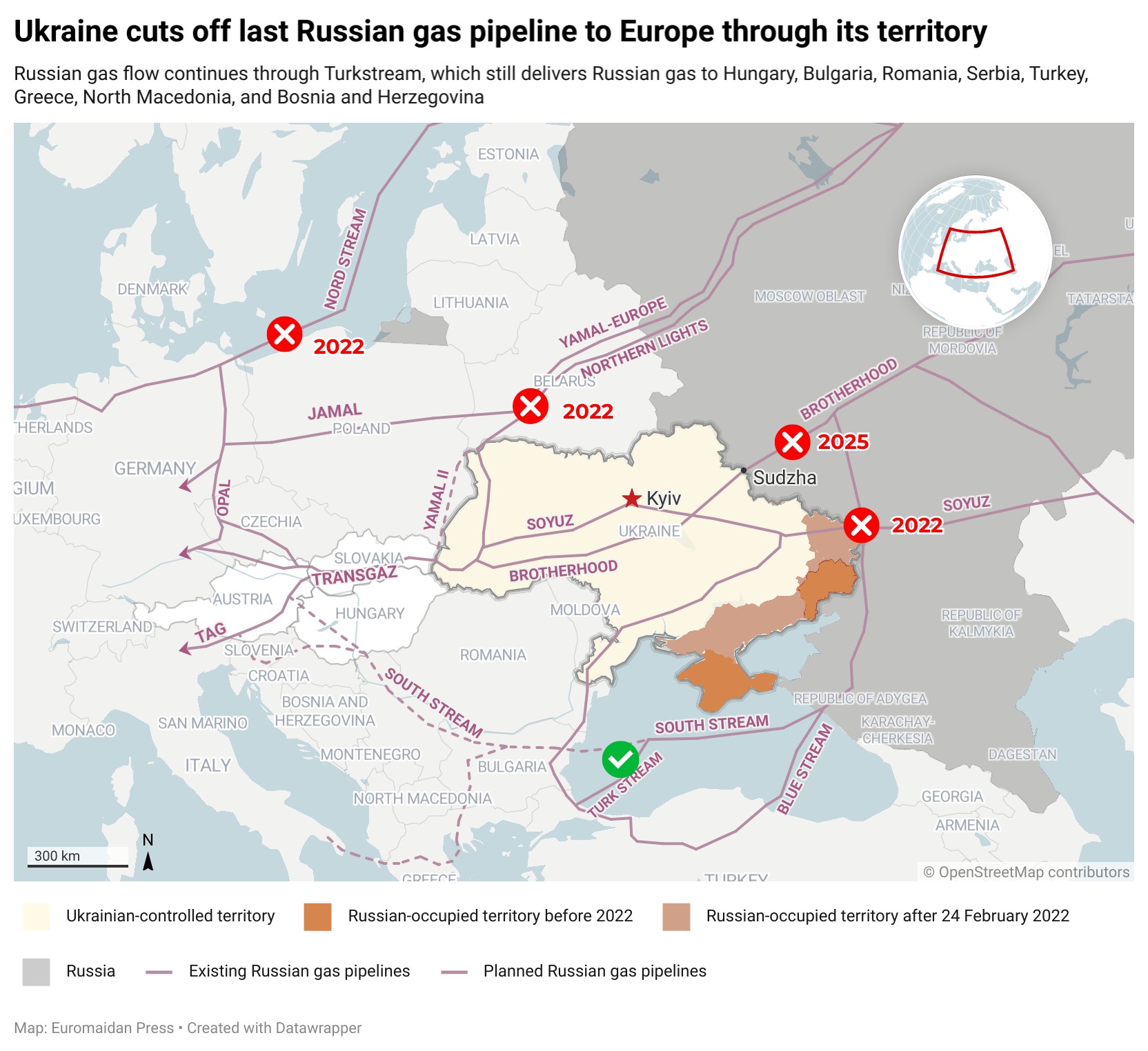

Moscow proved remarkably accommodating in negotiations, primarily because the regime's survival hinged on oil and gas revenues. This eagerness manifested in major infrastructure projects: the "Urengoy - Pomary - Uzhhorod" pipeline in 1981, followed by "Yamal - Europe" in 1984 (though the latter wouldn't become operational until 1996).

During this period, Europe and the USSR maintained a strictly professional relationship. Their energy partnership remained remarkably stable, weathering political storms that might have disrupted other trade relationships. By 1985, gas exports had become the USSR's primary source of foreign currency.

Russia's inheritance of the Soviet gas infrastructure in 1991 set the stage for the next chapter. While the 1990s saw intense negotiations over Ukrainian pipeline control - everyone needed revenue, after all - gas remained primarily a commercial matter.

The Putin era: from commerce to weapon

The dynamics shifted dramatically in the 2000s, driven by two major factors. First, the post-9/11 chaos in the Middle East reshuffled global energy politics. Second, Putin and his associates masterfully crafted corruption-laced deals that ensnared European and Ukrainian business circles and political figures. Gas transformed from a commercial commodity into a political instrument.

Nord Stream 1's construction began in 2001, while 2006-2009 saw Russia aggressively vying for control over Ukraine's gas transit system. The early 2010s brought plans for additional "diversification" routes.

Remarkably, this dependency survived the Crimean crisis. Though the EU made modest efforts to diversify its energy sources, particularly through LNG imports, significant change only came with Russia's 2022 invasion - or more precisely, with Ukraine's successful resistance.

The Asian market myth

Claims that Asia could replace Europe as Russia's primary gas market ignore several crucial realities. The Asian market remains a distinctly inferior alternative, even as a stopgap measure. Several factors make this evident:

- Logistics heavily favor Europe - most existing infrastructure points westward, making European delivery both cheaper and faster than Asian alternatives

- European market dynamics historically yielded higher prices, as competition and environmental regulations made Russian imports particularly attractive

- Russia's self-inflicted reputation damage through political manipulation and warfare has severely limited its negotiating position for long-term contracts in both Europe and Asia

- Asia enjoys abundant alternatives with shorter supply routes - China, the prime potential customer for Russian gas, has diverse options from Qatar to Turkmenistan, Iran to Southeast Asia and Africa

Putin's strategic defeat

This shift represents a profound political and economic setback for Putin's Russia. The implications are far-reaching:

- The financial impact of losing the European market will significantly reduce foreign currency earnings and exacerbate budget deficits

- Russia has surrendered one of its primary tools for influencing European politics through corruption - explaining the anxious reactions from figures like Fico and Orbán

- Europe's aggressive pursuit of alternatives, from American LNG to Norwegian and Algerian supplies, makes Russia's return to the market improbable even after the war

This situation perfectly exemplifies how Putin sacrificed a crucial instrument of economic stability - originally designed to sustain the USSR and later Russia - for short-sighted political and military adventures. It stands as testament to his place among Russia's most strategically inept leaders, rivaling the missteps of Nicholas II.

Related:

- Russian-backed Transnistria rejects EU gas despite supply crisis

- Russian gas cutoff triggers rolling blackouts in Moldova’s pro-Russian Transnistria

- Gas supply ends in Moldovan Transnistria after Ukraine halts Russian gas transit

- “Historic event”: Ukraine halts Russian gas flow to Europe

- Politico: Russian gas cutoff leaves Slovakia stable despite Fico’s fearmongering

- The secret Soviet council which established the Kremlin’s gas monopoly on Europe