Liubov Vozniuk (Cherkasy):

The famine hurts me even now. My parents, the Klymenkos - Mykhailo and Varvara with my sister Mariya survived the famine. And Brother Myshko died. The mother caught typhoid fever, the father became swollen.

The people, weakened by hunger, were just lying there, and neighbors helped them as they could.

Mariya left her home and wandered along the tyns [wattle fences typical for Ukrainian villages - ed.] and slept just there. She remembered that children ate kashkas - that's how we called the acacia blossom, and some other plants. Good people shared what they could. Then she returned home...

My mother's father Fedir Lytvyn died of starvation too. He refused to eat for the sake of the children surviving. A dray with a coachman was assigned to circulate and gather the corpses. When he came to us and looked at us, who were faint with hunger, he said, "Let me take the wife too, because when I reach the cemetery, she will be dead too, in order not to come here for the second time." Daughter Oksana grasped her mother and didn't let him. Then my grandmother lived 32 more years after the Holodomor. After the Holodomor, the coachman with one woman poked fun at her that he didn't take her then and she was still "loitering about."

Now I think that it was an impetus to live for my parents. My mother walked on her hunkers to their vegetable garden, gathered something there, and cooked a soup. Myshko poked it with a spoon, looked sullenly at the mother and refused to eat it. And died then. The mother's sister wrapped him in a bed cover and carried him away to the cemetery that was nearby. She put him in a grave, in a niche near an old woman. And from her other side, another child already laid. I also saw that small grave, they had no time to gid the graves then and put several people in one.

Earthed grains

When my grandfather with my father moved from Zhytomyr Oblast to a village that died out from hunger in Mykolayiv Oblast, they were offered to resettle.

After he discovered the nearby places and mounds, my great-grandfather returned to the hut, took a shovel and called my grandfather to follow. He brought him to a mound overgrown with grass and trees, took a shovel and dug a bit. And there instead of soil were rotten germinated grains [which were buried there after having been confiscated from the peasants. The Communist leadership did not manage to sell all the stolen grain - ed]. The great-grandfather pointed it out and commanded the grandfather not to forget it and pass the truth on to th generations.

They survived the starvation, and there were a lot of such mounds. Having discovered the truth, they couldn't stay in someone's house with the horrible past, in a village where the entire population died. They returned to their hunger-torn Zhytomyr Oblast.

Ukrainians in Kuban starved too

I am originally from Kuban [a region in south Russia mostly populated by Ukrainian settlers as of the Holodomor times - ed.], the famine had covered this fertile land too. Both grandmother and mother told us about it. People from towns wandered through hamlets hoping to exchange pottery, things for anything edible.

The grandmother baked scones from atriplex and oilcakes, they ate dandelions, plant roots. They also told that 1933 was droughty very much. People feared to pick up an ear of wheat, let alone to steal grain.

My father-in-law was born in the village of Chaplynka, Dnipro Oblast. He lost his parents in the Holodomor, and three siblings. His elder sister survived because at that time she was married and left home.

The father-in-law, then a 10-year-old boy, fled to Dnipropetrovsk [now the city of Dnipro - ed.] and lived there at a cemetery for several months. He fed on lizards, birds, plants. Then he was put into an orphanage as a homeless boy. Until the end of his life, he looked after the bread to be always present at home. In the dead of night, he could go to a shop if not much bread remained at home.

When we visited our grandmother, she told us horrible stories about the famine and showed to us, children, a home where a woman had eaten her daughter. That girl came to my grandmother's children to play and then disappeared.

"Some 40 close relatives died"

I learned about the Holodomor as a kid in 1984 thanks to the "enemy voices" [that's how the Soviet propaganda dubbed the Western radio stations broadcast to the USSR - ed.] - my parents always listened to the "Voice of America" at 5 or 6 a.m., as well as Radio Liberty. I was so much astonished that just when I came to my mother's village, I questioned my grandmother and later my grandfather in my father's village. Some 40 close relatives of my grandparents died - their brothers, sisters, parents.

The brother of my grandfather - mother's father - had 13 children. When all their grains were confiscated, one communist seized even a cauldron with kidney beans, boiling for borscht. His wife crept on her knees to the gates, soliciting to leave food for children. The entire family died. In winter, my father's uncle, then 12-year-old boy, found five onions among clods [on a field], that would anyway rot there. A communist spotted it, caught up with him and beat him to death, thrashing him with his Nagan [revolver] on his head.

Only my grandfather and grandmother saved themselves from genocide, escaping to the [industrial part of the] Donbas, then to Poti, Georgia back in the collectivization times. Another grandfather fled to Chechnya. And one more grandmother survived the famine in the city of Pryluky.

A dream of a big loaf of bread

As my gramma told, local scumbags who didn't do any job and who weren't respected by anyone, were the ones confiscating grains and any other foodstuffs. They were given firearms and power, so they kicked off the arbitrariness. The authorities signed the orders, and they fulfilled the orders in hundred-fold volumes. My grandmother lost her father then, he died with hunger.

My mother was born in 1923. In her childhood, he dreamed to buy a big loaf of bread and eat to satiety, and sate her mother. Such childhood dreams she had.

Seeds

My gramma and great-grandmother survived the Holodomor.

The grandmother was about to die after they exchanged at a marketplace some sauce for a glass of amaranth seeds [kind of a weed - ed.], but they turned out to be the seeds of henbane, thornapple [noxious plants - ed.]. As she had started eating them, her tongue failed her. Some good people saved her and bought something in a drugstore to save her.

"He almost couldn't feel the taste of food"

My grandmother is from Volhynia [the historic region which included modern oblasts of Volyn, Rivne and parts of Zhytomyr, Khmelnytskyi, Ternopil - the Holodomor raged in Soviet-occupied Volhynia parts while there was no famine in its areas under the Polish rule - ed.]. They cooked the bark of trees in winter, cones, and in summer they ate mushrooms and berries from the forest, orach [saltbush weed - ed].

The grandfather was originally from Khmelnytskyi Oblast, and they survived thanks to frozen beetroots, which they, young kids, dug out of the snow. Due to those frozen beetroots, he almost couldn't feel the taste of food till his dying day. They also ate a carcass of a dead horse. That's why nobody died in his family. And in a nearby village, several children were eaten, all told that thereafter and even showed the house where the cannibals lived.

A cow

My gramma was born in 1915 in the village of Pylyponka, Zhytomyr Oblast. She told that they survived thanks to a cow. My great didn't slaughter it and the family had milk. Those who couldn't stand and slaughtered their cattle out of hunger didn't survive [in many areas all livestock was also confiscated together with food - ed.].

My gramma told that she went to pick up ears of wheat at night. Once the Red Army soldiers caught her, they poured out everything she gathered from her cauldron, but let her go. She also told that there were people with firearms who went from home to home and punctured floors with long metal rods to find the hidden grains.

She told about the atriplex bread, and about the people who couldn't go out of their homes and just shouted, "I want to eat!"

According to my grandmother, her village suffered from three famines. In the second one, before the [WWII] war, she lost two children. After that, she gave birth to two more children and the youngest was my mother.

"Two of them survived"

My grandmother lived in Bila Tserkva Raion [central Ukraine] and two of them survived - she and her sister. Her mother and three children died, and her father went to find some food and didn't come back.

From my childhood, I recall her stories about acorns, rotten peelings they were eating. The grandmother and her sister ate poisonous fungi because hunger was unbearable. They came to their senses only in an orphanage.

I could never get why the history textbooks didn't tell about this inhuman tragedy - I was at school in the Soviet era in the 1970s. That's the very time I, still a teenager, started to realize the mendacity and dreadfulness of the Soviet regime.

It's been a long time since I live abroad, but I always tell to my children about this crime of the Soviet authorities. In 2015 when my daughter was 15, we visited Kyiv in summer and the first thing she wanted to see there was the Holodomor Memorial. And she found the names from our family in the Memorial book - that year she told about the Holodomor at school in the days when the Holocaust victims were commemorated.

Food parcels prohibited

My husband's gramma told me that in the Holodomor times she was in Georgia as a seasonal labor migrant and tried to send a parcel with food by post. She was put it bluntly that she could send clothes to Ukraine, but not food.

Donbas starved too

My grandmother went through the Holodomor and told me how she managed to survive and save my mother from death. She was lucky to be hired by Bulgarians who had some plots in concession. She worked as a farm hand for them for food. But she was strictly prohibited to take even a single grain home.

The mother survived because my grandmother had enough breast milk. And what is interesting, turns out that Bulgarians were not affected, and Ukrainians suffered because all the food they could eat was confiscated. Also, my mother's family was saved by the fact that my gramma had salt and she walked to exchange the salt for food. She visited neighboring oblasts, the Russian ones as I get it, because she lived near Yenakiieve [Donetsk Oblast] then.

Luck

My grandfathers were "lucky." In 1929, saving from the total collectivization and de-kulakization, they left all their gainings - homes, agricultural things. They loaded the family to a cart and went to the construction works of the Leningrad-Odesa railway in Leningrad Oblast. And they returned to Ukraine only in 6 years as "proletarians" with the Southeastern Railway. At that moment the kolkhoz order was already imposed after the Holodomor.

Read more:

- ‘Stalin prepared the Holodomor the same way Hitler did the Holocaust,’ Hrynevych says

- See which countries recognize Ukraine’s Holodomor famine as genocide on an interactive map

- Treebark pancakes and pinecone soup: “dishes” from Ukrainian 1930’s Holodomor famine served in Brussels

- Ukraine suffered the most deaths in the Holodomor, while Kazakhstan had the highest percentage loss of population

- British House of Commons once again calls to recognize the Holodomor as genocide

- Why the Holodomor is genocide under UN convention: On Anne Applebaum’s Red Famine

- Washington becomes first US state to recognize Holodomor as genocide

- Portugal recognizes Ukraine’s Holodomor famine as genocide

- It’s long past time to identify and shame Holodomor deniers

- The Holodomor of 1932-33. Why Stalin feared Ukrainians

- So how many Ukrainians died in the Holodomor?

- HOLODOMOR 1933: Light a candle in your window

- Documents reveal Soviet repressions against those resisting Holodomor genocidal famine

- The history behind “Bitter Harvest,” dramatic movie about the Holodomor

- Why compare the Holodomor and the Holocaust

- Holodomor or death by starvation changes people’s genotype, say psychologists

- Documents show massive export of products from Ukraine during Holodomor

- History, Identity and Holodomor Denial: Russia’s continued assault on Ukraine

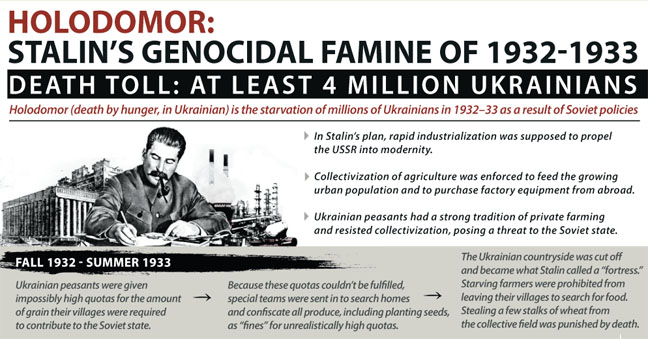

- Holodomor: Stalin’s genocidal famine of 1932-1933 | Infographic

- Stalin’s genocidal Holodomor campaign of 1932-33. What we know vs the denialist lies

- Chief librarian in Feodosia (Crimea) fined for displaying books on Holodomor

- Dancing with Stalin. The Holodomor genocide famine in Ukraine

- Stalin’s terror famine killed Ukrainians at twice the rate of other nationalities