The decolonization of Slavic and Eastern European studies has become a prominent topic of discussion amid Russia’s war against Ukraine.

“The war in Ukraine began to tear off the curtain that obscured a world of which American and European students of things Slavic have had no idea,” remarked acclaimed postcolonial scholar Ewa Thompson. Thompson added that many Slavic departments in the Western world are essentially Russian departments, making it unlikely that Russian literature and language teachers will act against their self-interest.

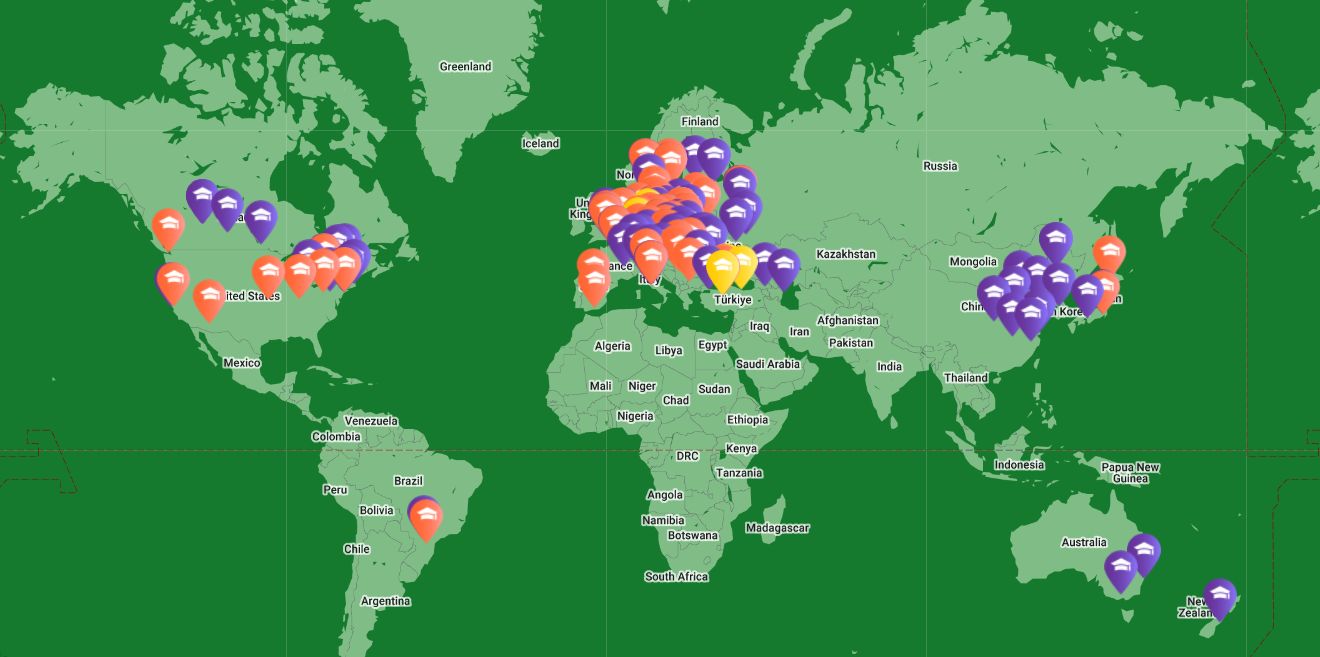

Two years ago, the Ukrainian Institute identified over 160 centers of Ukrainian studies worldwide, including Crimean Tatar studies in over 30 countries.

The Ukrainian Studies Go Global project showed, though, that Ukrainian studies are represented in 57 universities out of the world’s top 100 while just a handful are full-fledged centers.

In a survey of 300 top-ranked universities in the United States, European Union, Canada, and the UK, according to the Webometrics Ranking, many centers and departments were still labeled as Russian or included “Russian” in their names.

This situation urges Ukraine to reconsider its representation in Western academia, which has often been responsible for a skewed and inadequate portrayal of Ukraine, sometimes creating the impression that there is nothing in the region except Russia. A critical review of how the world speaks about Ukraine is long overdue to break free from the imperial paradigms and colonial simplifications.

For Western academia, several points should be considered to make decolonization and deimperialization more effective.

First, the hegemony of Russian studies scholars is unhealthy for the advancement of academia.

Diversity is crucial for knowledge exchange and connecting research with reality. Scholars with a sufficient understanding of regional histories, languages, cultures, and politics should be relied upon. Experts on Ukraine should have a working knowledge of Ukrainian and use original sources and archives, not Russian ones that retell regional matters in a propagandist way.

The responsibility of Russian studies scholars for the current state of affairs is challenging. According to Taras Kuzio, research centers are mainly run by scholars of Russia who dominate the field of post-Soviet studies and Eurasian affairs, acting as gatekeepers to what is published.

Some continue to misconstrue reality, playing into Russia’s hands while Ukraine loses lives daily in the war.

While academics deny the possibility of Russian agents infiltrating academia, a Russian professor of political science was recently convicted of espionage charges in Estonia. The authorities claimed he was recruited by Russian security services in the 1990s.

Soviet security services commonly recruited agents among professors or infiltrated foreign universities. After KGB archives in Ukraine were declassified, some operations became known, such as the exemplary case of the Swedish professor tricked by a KGB agent, a local history scientist in Estonia, who aimed to get a cover for his task in Sweden.

KGB's cooperation with Western scholars aimed to undermine the Ukrainian diaspora and causes, such as hindering international recognition and memorialization of the 1932–1933 Holodomor, the Soviet famine that took the lives of roughly four million Ukrainians.

Fifty years later, Holodomor recognition remains a political, not academic, issue. Only once the Ukrainian army started repelling Russian troops amid the full-scale war did the avalanche of recognition acts go global.

Second, the protracted war has highlighted the problem of Russian dominance in sources.

Many Western research centers received substantial financial aid from Russian government organizations and oligarchs, creating networks of influence worldwide.

The ASEEES Cohen-Tucker Prize controversy illustrates this issue. Funded by Stephen Cohen and Katrina vanden Heuvel in 2015, the prize faced criticism over the proposition of its renaming in honor of Cohen, the Soviet history scientist who had gained notoriety for the support of Russian President Putin and anti-Ukrainian Russian propaganda.

Increasing job positions for Ukrainian scholars, as recently done at the University of Michigan, is crucial. Offering qualified courses on Ukraine and in Ukrainian, as well as other regional languages, will reveal new worlds for students and future regional experts.

Accessibility is another important issue, ranging from Western scholars’ access to Ukrainian archives and translation of Ukrainian sources to student exchanges and conference attendance for Ukrainian scholars. This requires significant resources and effort but is necessary.

Few Ukrainian participants can afford to attend conferences in North America or the UK, and extending online participation and creating more funding opportunities would increase diversity and inclusivity. The Annual Danyliw Seminar is a good example. Increasing the involvement of scholars from regions occupied by Russia, either ideologically or literally, is also productive.

Thirdly, the approach to discussing Ukraine should avoid what the Indian scholar Dipesh Chakrabarty termed “asymmetric ignorance.”

Even when acknowledging Ukrainian authenticity, knowledge of Russian matters is often considered sufficient for discussing Ukraine. Ukrainian subjectivity should be central to the academic discourse on Ukraine.

It is vital to stop relying on the colonizer’s language and filtering knowledge on Ukraine through Russian propaganda. The Ukrainian intellectual Oksana Zabuzhko described imperialism as the usurpation of the right to name oneself. Developing a proper, deimperialized vocabulary to explain Ukraine is critical.

New solutions are possible, such as the German Federal Foreign Office’s switch from “Kiew” to “Kyjiv.”

Von „Kiew“ auf „#Kyjiw“: Was für viele schon länger gängige Praxis ist, ändert sich nun auch im „Länderverzeichnis für den amtlichen Gebrauch“. Damit wird jetzt im deutschen Amtsverkehr die ukrainische Schreibweise für Kyjiw verwendet. 1/2 pic.twitter.com/leTNKIclMk

— Auswärtiges Amt (@AuswaertigesAmt) February 23, 2024

Non-critical admiration for Russia is pervasive in academia. US universities continue to promote Russian courses with stereotyped descriptions and Moscow-centered narratives as Vox Ukraine showed in late 2023. My question to top university’s course creators about addressing Leo Tolstoy’s inhumane descriptions in “Anna Karenina” and domestic violence remains unanswered.

University curricula and study methods need revision, from advertisements and language requirements to the mandatory use of Ukrainian sources and archives.

Recognizing Ukrainian studies as self-contained and needing no external approval is essential. “Decolonization” of Ukraine’s history and culture should be left to Ukraine, but it must be accompanied by the “de-imperialization” of Western academia’s imperial optics, pointed out the historian Andrii Zayarnyuk.

Acknowledging the existence and legitimacy of Ukrainian studies, including Ukrainian history, is a simple first step. All efforts should aim to create a more efficient and balanced regional studies architecture.

US academia still in thrall of “great Russia” myth

Positive changes are occurring across academia despite its intrinsic clumsiness. Some research centers have been renamed, such as the department at Dartmouth College (petitioned by a student), and some Russian studies scholars are rethinking their attitudes and principles. Many Western universities strongly support Ukrainian scholars, such as the IU-Ukraine Nonresidential Scholars Program at Indiana University, which I am proud to be part of.

However, Russian hegemony must be appropriately acknowledged and dealt with, as it poses an ontological threat to academia. An essential part of this process is self-analysis by both scholars and academic institutions.

Amid the largest war in Europe since World War II, there is no more time for delaying difficult conversations and uncomfortable decisions.

Editor's note. The opinions expressed in our Opinion section belong to their authors. Euromaidan Press' editorial team may or may not share them.

Submit an opinion to Euromaidan Press

Related:

- “Decolonization will not be stopped”: Ukraine expands movement against Russian cultural imperialism

- Inside Ukraine’s covert program preparing Russia’s minorities for independence

- “Do Svidaniya” to Russo-centrism: Western schools start decolonizing Eastern Europe studies

- US academia still in thrall of “great Russia” myth