Ukrinform, one of Ukraine's two state news medias, finds itself in the center of a scandal that brings back memories of an era of state censorship and media seizure, raising concerns for Ukrainian media freedom.

Its former director Oleksii Matsuka, once celebrated as one of Reporters Without Borders' 100 Information Heroes, allegedly attempted to censor content in favor of the authorities, particularly the Office of the President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, during his six-month tenure. This included the circulating of "desirable" and "undesirable" guest lists for journalists, leading to the departure of dozens of media workers.

The scandal gained international attention, with Ukrainian journalists meeting G7 ambassadors to raise concerns about pressure from the President's Office.

Following the scandal, Oleksii Matsuka was replaced by Serhii Cherevatyi, a military journalist and former military spokesman. While this may seem like a positive move given the military's current authority in Ukrainian society, questions remain about the lack of an open competition or the creation of an oversight board to ensure Ukrinform's independence.

The explosive Ukrainska Pravda report on this matter, co-authored by Roman Kravets and Anhelina Strashkulych, the latter a former Ukrinform employee who witnessed some of the events, shook the media landscape. Few realized the full scale of the agency's turmoil until then. Euromaidan Press sought to investigate further, benefiting from Ukrainska Pravda's revelations.

Bonuses, advisors, and influence

Founded in 1918, Ukrinform has seen various governments over its century-plus lifetime, united by the belief that the state media should serve those in power.

Memories are still fresh of the agency’s servitude to the ruling Party of Regions as Ukraine was headed down the path of authoritarianism during the presidency of Viktor Yanukovych, Ukrainska Pravda writes. To this day, Ukrinform’s photobank contain no photos from the Euromaidan protests that unseated Yanukovych in 2014: the agency’s photographers were forbidden from operating there.

After the Euromaidan Revolution, as the spirit of democratic renewal was in the air, Ukrinform received a new director. Veteran journalist Oleksandr Kharchenko managed to raise the agency’s status from “party newsletter” to a reliable media that regularly made it to the reputable whitelist compiled by the Institute of Mass Information.

As it appears, the agency’s independence ruffled feathers in the current administration under President Zelenskyy.

In November 2023, as Kharchenko’s 10-year contract expired, Oleksii Matsuka, a native of Russian-occupied Donetsk, was appointed director general. His background included founding Novosti Donbasa, working at RFE/RL's Kyiv bureau, and heading the Russian-language state TV channel FREEDOM.

Matsuka also participated in Western journalism programs and organized the Donbas Media Forum with Western funding. He received accolades like being named one of Reporters Without Borders' 100 Information Heroes in 2014 and the International Press Freedom Award from Canadian Journalists for Free Expression in 2014.

With over 300 staff across Ukraine and 11 foreign bureaus, Matsuka needed a leadership team. The President's Office "helped" by bringing in people close to Andriy Yermak, the Head of the Ukrainian President’s Office. Yehor Sihariov, with no media experience but ties to Yermak's advisors Daria Zarivna and Vladyslav Vlasiuk, became Matsuka's deputy for personnel, the Ukrainska Pravda investigation says.

Vlasiuk regularly visited Ukrinform, advising Sihariov on operations like the website, marketing and communications. Sihariov hired people affiliated with Zarivna's Vector magazine, such as its CEO consulting the marketing team. Zarivna claimed distance from Vector since the invasion.

"Overall, I don't see a conspiracy: good professionals are scarce. But if asked, I would have objected. I just didn't know," she told Ukrainska Pravda.

Another Yermak advisor, Serhiy Leshchenko, launched his show on Ukrinform's YouTube channel, claiming it was his personal initiative, not the Office's.

"We discussed how to diversify the YouTube lineup, with a frontline diary, more eye-catching titles. I suggested publishing more short videos on Telegram and being more active on X. That's all we talked about," said Leshchenko.

Matsuka secured hefty bonuses for himself and his deputy Sihariov from January to April 2024 - 287% of their base salaries, according to Ukraine's Ministry of Culture and Information Policy. In contrast, long-time deputy director Iryna Cherednychenko received only a 40% bonus.

Censorship allegations

However, the primary accusation against Oleksiy Matsuka is that he engaged in censorship to favor the current Ukrainian authorities. According to Ukrinform employees who spoke on conditions of anonymity with Ukrainska Pravda, Matsuka regularly shared topics in editorial chats that were "desirable to cover" and provided guidance on how to "better explain" political, military, and international events.

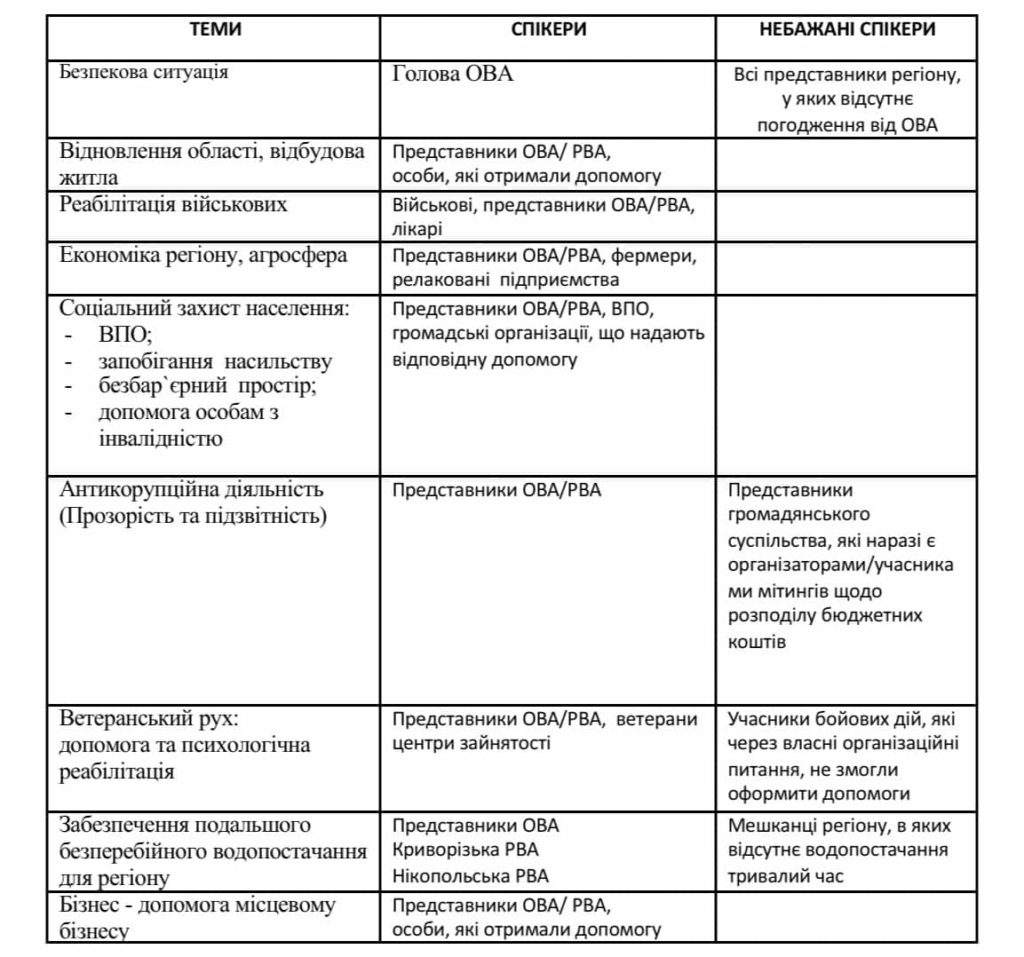

While such practices may exist to some extent in every editorial office, Matsuka's actions went beyond the norm by distributing lists of "desirable" and "undesirable" interlocutors and experts.

In December 2023, Matsuka sent to Ukrinform's regional editorial office files recommending topics for local correspondents and who they should/shouldn't get comments from, Ukrinform employees told Ukrainska Pravda. The "undesirable" voices included opposition figures, organizations, local politicians critical of the government, but also regular citizens directly impacted by the issues.

For example, on water supply disruptions in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, long-suffering residents without water were "undesirable." For veteran assistance, veterans themselves unable to access aid were deemed undesirable speakers.

As well, Matsuka’s team instructed Ukrinform’s SMM team to not give airtime to military personalities who may be perceived as political competitors to President Zelenskyy, such as former Commander-in-Chief Valeriy Zaluzhnyi.

This contradicted Matsuka's media awards and Western journalism training.

These "temnyky" (literally "themes"), believed to have been invented by Russian political strategists, became widely used under the pro-Russian politician Viktor Medvedchuk, who headed Kuchma's administration.

Media outlets were pressured to comply with these recommendations under threat of state inspections, broadcasting license revocations, staff demotions, salary reductions, job losses, and even physical violence, as in the case of Georgii Gongadze, the founder of Ukrainska Pravda, who was killed in 2000.

The practice of "temnyky" only ceased after the Orange Revolution in 2004, when Viktor Yushchenko became president.

Despite Matsuka's attempts to control the narrative, Ukrinform employees refused to follow his instructions. When Matsuka found out that his “temnyky” had spread throughout the agency, he got scared.

"At first, he denied everything, then said that he had only sent two columns, and someone else had added the third one [the “undesirable speakers”]. After some time, he ordered the regional correspondents to make materials with all the “undesirable speakers,”"said one of the agency's employees.

The President's Office denied involvement, while Matsuka refused to explain the documents' origins.

As a result of Matsuka's influence, the Institute of Mass Information (IMI) noted a bias toward the President’s Office in Ukrinform's news feed.

"In November 2023, the number of mentions of Yermak on Ukrinform increased by 28% compared to September. In December, it increased by 60% and remained at that level until February 2024," explained IMI director Oksana Romaniuk.

Because of this, the agency dropped out of IMI’s white list of reliable media in 2024.

G7 Ambassadors shocked

Oleksiy Matsuka's appointment triggered an exodus of 45 employees from Ukrinform, including Deputy Director Maryna Synhaivska, who oversaw creative departments.

In late January 2024, Synhaivska represented Ukrinform at a meeting with G7 ambassadors, who had invited several Ukrainian media outlets to investigate reported pressure from the President's Office. Synhaivska informed them about the new leadership's censorship, presenting documents circulated to regional offices as evidence.

"Everyone was in shock: the ambassadors and us too. Everything said after Synhaivska paled in comparison," said one meeting participant, Ukrainska Pravda reported.

The President's Office spent months deliberating a response after learning of this meeting. Options like an independent oversight board or monitoring expert were considered to uphold standards. Ultimately, they decided to remove Matsuka, who announced his resignation on 24 May 2024.

From the frontlines to the newsroom

On the day of Matsuka's resignation, Ukrinform appointed a new director - Colonel Serhiy Cherevatyi, a military journalist, political scientist and former spokesperson for Ukraine's Eastern Military Grouping after Russia's invasion.

Cherevatyi said the offer to lead Ukrinform caught him by surprise just days prior, but he viewed it as "serving the country."

"I will study the situation first. I understand there are issues. I'll examine them in detail, then make decisions. For now, everything remains as is. I wasn't prepared for this role for two months. I made the decision, roughly speaking, within two days," he stated.

While military circles praise Cherevatyi's managerial abilities and "controlled communications" expertise, doubts exist over his lack of experience running a civilian media outlet. Some believe an open competition was needed instead of appointing a military officer.

"I see a direct conflict of interest in appointing a military person as Ukrinform's head," said journalist Oksana Romaniuk from the Institute of Mass Information, noting the differing duties of the military and media.

The key question, journalists say, is how to ensure the state news agency remains independent from authorities during wartime, regardless of its leadership — a challenging task despite some Ukrainian precedents.

Suspilne success story

Suspilne, Ukraine's National Public Broadcasting Company, can serve as a positive example of how a media with state funding can at the same time be reliable and independent. Its creation in 2014 is viewed as a successful post-Euromaidan reform.

According to Detektor Media watchdog, Suspilne is one of the few TV channels offering politically independent content, providing an alternative to politicians' efforts to manipulate public discourse for electoral gains.

Suspilne's independence is safeguarded by a Supervisory Board overseeing its management. The board consists of representatives from parliamentary factions and civic associations serving five-year terms.

However, in April 2024, journalists and media groups accused certain politicians and officials of "informational and institutional attacks" aimed at undermining Suspilne's independence and funding stability. This included an MP from Zelenskyy's party spreading misinformation about Suspilne's budget and board compensation.

These perceived threats to Suspilne's autonomy are seen as dangers to Ukraine's media plurality and democracy.

Meanwhile, during a working visit to Finland, Suspilne's CEO Mykola Chernotytskyi stated that while there is no censorship in Ukraine, only military restrictions.

"It's very important that military restrictions don't turn into political censorship. But I cannot imagine censorship being introduced. We have sufficient media freedom," he said.

Chernotytskyi cited Ukraine's rise of 18 positions to 61st out of 180 countries in the 2024 World Press Freedom Index as evidence of increasing press freedoms.

***

Ukraine's ongoing journey towards a stronger democracy relies heavily on the country's ability to safeguard the independence and integrity of its media institutions. The Ukrinform controversy has highlighted the challenges faced by state media in maintaining editorial autonomy and resisting political pressures.

In contrast, the successful establishment of Suspilne as an independent public broadcaster, overseen by a Supervisory Board, offers a model for insulatingmedia organizations from undue influence. However, recent attacks on Suspilne's independence and funding stability serve as a reminder of the constant threats to media freedom and the need for robust defense mechanisms.

Read more:

- Ukrainian media coalition decries "targeting" of journalists critical of authorities

- Bihus exposé: Ukraine's SBU illegally surveilled investigative journalists

- Zelenskyy fires security service chief accused of "weaponized draft" against journalist

- Ukraine launches criminal probe into "weaponized draft" against SBU whistleblower

- Draft summons used as "punishment" for Ukrainian journalist exposing SBU official's luxury real estate