That Russia pursues expansionist ambitions is no secret. Nor is the fact that it utilizes soft power methods in addition to purely military means. However, little attention is usually paid to the organizational structure and programmatic activities that serve as the Kremlin’s transmission mechanisms in its “cultural offensive” campaigns, apart from connections to “dirty” money used for such purposes.

In the spring of 2022, a team of authors under the direction of the Ukrainian Institute examined the operational aspects of three perhaps most prominent and well-known Russian organizations:

- Rossotrudnichestvo

- “Russkyi Mir” [Russian World] Foundation

- the Gorchakov Fund.

The findings are detailed in three papers (here, here, and here). A revised and updated version was recently published as the book Russian Cultural Diplomacy Under Putin by ibidem-Verlag.

The main takeaway is that despite the unprovoked war against Ukraine and bellicose international conduct, Russia's “soft power” organizations are still operating and constitute a considerable problem for the West. While the efficiency of Russia’s cultural diplomacy might be compromised by systematic underfunding, the sheer scope of organizations like Rossotrudnichestvo or the “Russkyi Mir” Foundation, coupled with their increased prioritization after 2022, proliferation in nations with dominating anti-Western dispositions and a persistence of pro-Russian sentiments, remains a serious strategic threat.

Beyond European audiences that have potentially become less receptive to blatant propaganda, Russia’s cultural diplomacy arsenal will most probably try to target audiences in societies that are still expected to oscillate between the West and its challengers, such as in Africa, Latin America, or India.

Now let us review the organizational aspects of these institutions in more detail.

Russia's cultural diplomacy: a child of imperial revanchism and revisionism

The Soviet Union's fall, seen by Russian elites as humiliating defeat, birthed revanchist ideas like “compatriots,” “Russian World,” and Gorchakovism, with the latter being a nod to Prince Aleksandr Gorchakov, tasked to rebuild Russia's international standing following its defeat in the Crimean War in 1856.

Unready to curb influence expectations, especially in post-Soviet states, yet having lost Communist zeal, they refined concepts to serve neo-imperial aims.

The late 1990s saw the term “Russian World,” initially denoting "the fact that there were as many Russians living abroad as within Russia proper.”

Under Putin, closer to the late 2000s, the Kremlin severely politicized this into the 2007 “Russkiy Mir” Foundation, headed by Viacheslav Nikonov, grandson of Stalin's associate Molotov who signed a secret non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany.

Likely recalling Valentin Pikul’s books, 1990s diplomats revived Aleksandr Gorchakov under Foreign Minister Evgeny Primakov Sr. Like Gorchakov in the 19th century, Primakov felt Russia just suffered a Crimea-esque defeat, needing reconsolidation and modernization.

After closed-door work with foreign diplomats —partly the Gorchakov Fund’s work—the hope was to revoke the humiliating status quo that came after 1991 by making target states’ diplomats more Russia-friendly.

Primakov’s grandson Evgeny now heads Rossotrudnichestvo. This institution with a long Soviet-era history, was also geared to modernize under Putin, with the ambitious goal to claim a presence in as many countries as possible and to win the “hearts and minds” of people in target countries by copying the Western models of cultural diplomatic and humanitarian aid organization.

Russian elites seem to have wanted Rossotrudnichestvo to become a Russian USAID.

Russian elites seem to have wanted Rossotrudnichestvo to be a Russian USAID.

The web of Russian cultural diplomacy

But what are their institutional capacities? Well, those vary and are currently in flux, particularly due to the limitations their representations abroad are facing because of sanctions and Russia's new geographical ambitions.

The most widely sprawling is Rossotrudnichestvo, whose foreign offices encompass the largest number of countries. These are rarely direct legal representations of Rossotrudnichestvo but are rather branches or departments of Russian embassies – a practice from Soviet times.

2022 and 2023 saw forced shutdowns of Rossotrudnichestvo’s offices in European countries, but also increased activities in Africa, with new “franchise” offices in Algeria, Egypt, Mali, and Sudan opening in 2022.

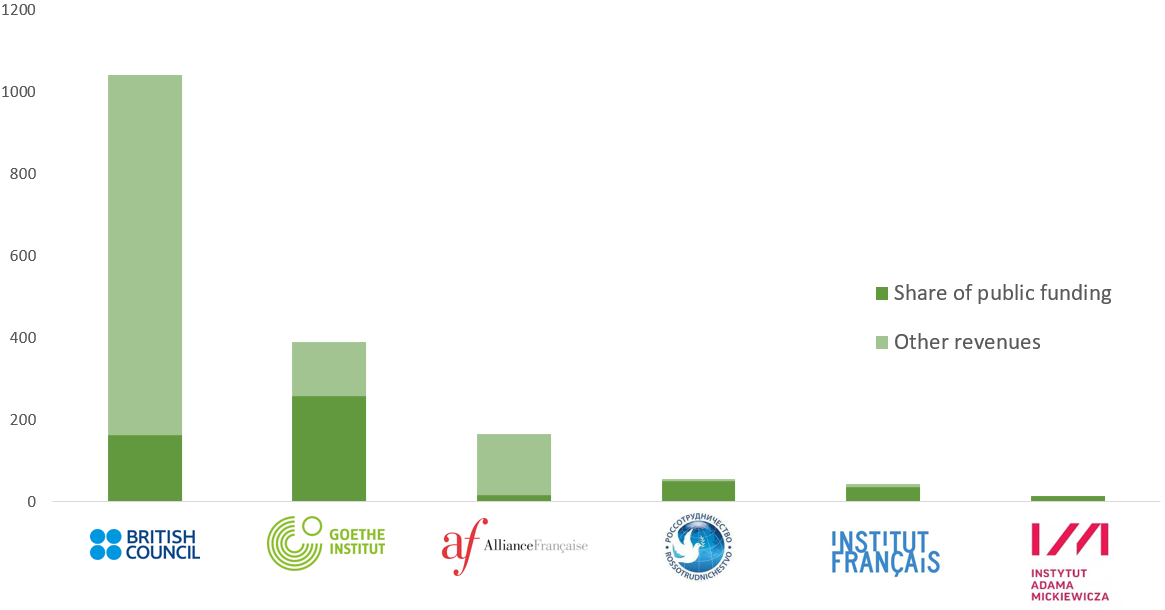

Rossotrudnichestvo’s annual expenditures amounted to €54.8 million in 2020, with 90% subsidized directly from the federal budget. Although immense, perhaps dictated by the organization’s sheer size, this does not loom as large, compared to Western peers.

Rossotrudnichestvo’s annual expenditures amounted to € 54.8 million in 2020, with 90% subsidized directly from the federal budget. Although this is an immense sum, perhaps dictated by the organization’s sheer size, it does not loom that large when compared to the organization’s Western peers.

Publicly funded cultural diplomacy institutions in Western countries and Rossotrudnichestvo

“Russkiy Mir,” founded under Putin’s reign, has sprawled to nearly a third of the world’s countries within the last decade and a half.

Trending Now

As of March 2022, the Foundation had 104 active Russian Centers (usually organized at university departments of Russian studies or at schools with an option of studying Russian) in 52 countries and 128 Cabinets of “Russkiy Mir” (less institutionalized units usually found at libraries and NGOs) in 57 countries.

Additionally, the Foundation’s website listed over 5700 “friendly organizations” in nearly 160 countries, though 2700 were in Russia.

“Russkiy Mir’s” main activities promote Russian language and literature by supporting educational activities abroad and engaging target communities of Russian philologists and researchers.

Though legally a non-commercial, non-state organization, it was jointly founded by the Education and Foreign Affairs Ministries and funded through them. Like Rossotrudnichestvo, it receives heavy government subsidies. According to available data, the Foundation’s expenditures strikingly increased in 2022 from €5.7 million to circa €38 million.

The Gorchakov Fund has the most modest budget among the three (circa €500,000 to €1.7 million annually) but more targeted audiences - young IR professionals expected to shape future policies. Programs address specific regions (like “Caucasian Dialogue” and “School on Central Asia”) or provide mobility opportunities to Russia-sympathetic professionals.

Corresponding to Russia’s immediate expansionist ambitions, the Fund has representations in Belarus and Georgia.

In December 2023, Rossotrudnichestvo gathered 30 international journalists and bloggers from Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova (Transnistria), and Uzbekistan in Moscow to study the expertise of Komsomolskaya Pravda, the Federation Council of Russia, and Moscow State University faculties -- all vehicles of state propaganda. Credit

Russian cultural influence still an active threat

Despite the 2022 invasion significantly altering the status of organizations like Rossotrudnichestvo, “Russkiy Mir” Foundation, and the Gorchakov Fund in Europe and North America through sanctions against leaders, their ambitions and activities remain not to be disregarded.

Although financial resources may seem underfunded compared to Western cultural diplomacy standards, these institutions continue to significantly challenge Western narratives. This poses a crucial concern given their potential ability to strategically adapt by adopting new Western public diplomacy means for serving Russian agendas.

In regions like Africa and Latin America, where public opinion vis-à-vis Russia's invasion of Ukraine still oscillates or even leans towards Russia, the extensive work of Kremlin-backed cultural diplomacy institutions, especially when coupled with Russian military or economic presence, is still a considerable threat.

One of the long-standing reasons behind it is the anticipated long-term orientation of the Kremlin and Russia’s elites for a confrontation with the West, and the ensuing dedication to expend on any means serving this purpose.

Ever since the increased spending on cultural diplomacy became possible in the 2000s thanks to revenues from natural resources, Russia has continued to fund its soft power institutions and will likely continue to do so as long as the economy allows.

Putting additional pressure on Russia’s budget by introducing new sanctions and overseeing compliance with the old ones is therefore crucial not only for limiting its resources to wage war against Ukraine, but also for encouraging Russian elites to withdraw funds from their heavily subsidized cultural diplomacy arsenal.

On a parallel track, promoting counternarratives is drastically needed. An ever-growing share of Russia's activities targets the so-called Global South, usually through both old memories of the benevolent Soviet Union (as opposed to the West’s colonialist past) and contemporary humanitarian aid provision, as well as cultural exports.

A thoroughly planned public diplomacy campaign aiming at Africa, Latin America, and South Asia (more specifically, India) and countering Russia’s interpretations of its war of aggression against Ukraine and politics in Eastern Europe, especially post-1991, is thus badly needed.

Featured photo: on December 7, a graffiti titled "Russia and Venezuela: Friendship Through the Ages" depicting the meeting between Russian Empress Catherine II and the hero of Venezuela's national liberation struggle Francisco Miranda was unveiled in Caracas. This is one of the projects of Rossotrudnichestvo, a Russian soft power institution. Photo: Russkiy Dom/FB

Related:

- Pushkin monuments disappear from Ukrainian streets following Lenin, as decolonization is underway

- Russian literature is an accomplice in war against Ukraine – literary critic

- Genocide, assimilation, theft: Kazakh historian reveals Russian colonialism’s ruthless playbook

- The myth of “historically Russian Crimea”: colonialism, deconstructed

- “Do Svidaniya” to Russo-centrism: Western schools start decolonizing Eastern Europe studies

- Russian World: the heresy driving Putin's war