Article by: Isaac Levі, Oleh Savytskyi

The policy of the G7 countries to impose a global price cap on Russian oil is no longer in effect. Russian oil is sold on world markets at prices well above $60 per barrel. A side effect of the G7's actions has been an increase in the volumes of Russian oil being transported on “shadow” tankers, with a rising number of dangerous oil transfer operations at sea. Russia is still heavily reliant on tankers owned or insured in countries implementing the price cap, which highlights the leverage that the policy has to lower Putin’s export revenues if fully monitored and enforced.

After Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Ukraine's allies imposed sanctions to limit the Kremlin's revenues. The European Union and the United Kingdom banned imports of Russian crude oil by sea in December 2022, and a ban on imports of petroleum products came into effect in February 2023. A policy was also introduced to limit services related to the shipment of Russian oil and oil products at a fee higher than the levels set by the G7 countries.

This policy aimed to reduce Russia's oil export revenues and stabilize world fuel prices. The countries implementing the policy, including G7 members, the EU, Norway, Switzerland, and Australia, imposed a price cap level on Russian oil at $60 per barrel in December 2022.

Buyers of Russian oil who violated the price cap restriction were denied access to critical services provided by companies in the coalition countries. These included internationally recognized ship insurance, as well as the ability to use the European tanker fleet, including vessels owned by Greece and Cyprus. Similar restrictions on oil products were introduced in February this year.

An analysis by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) showed that sanctions, together with price caps at the beginning of their implementation, reduced Russia's revenues by more than 160 million euros daily.

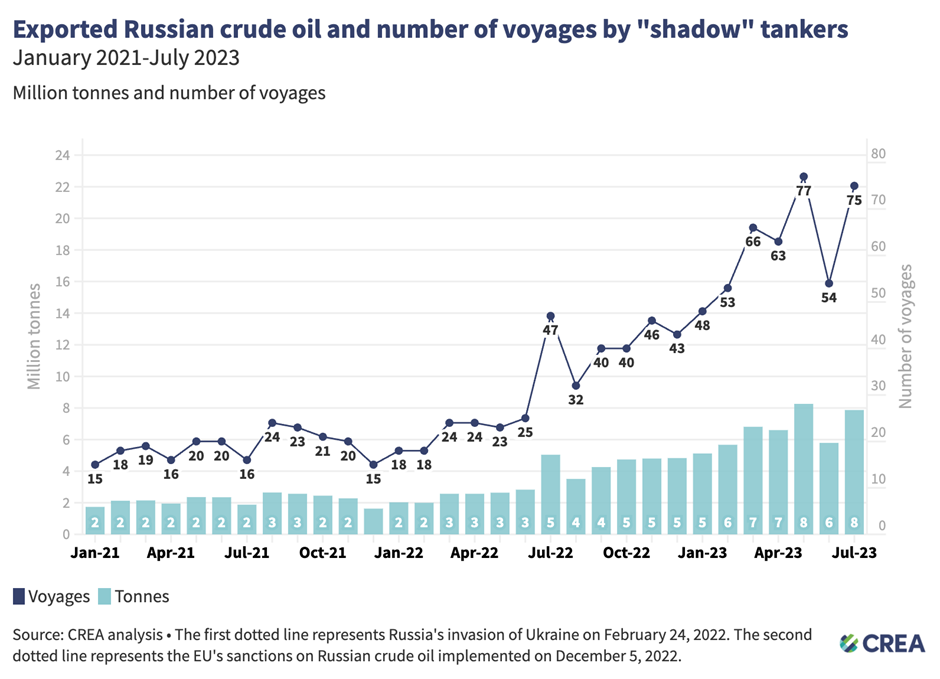

However, since the beginning of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine and especially after the imposition of sanctions, CREA data shows a sharp increase in the volume of Russian oil transported by “shadow” tankers.

G20 host India & member states’ addiction to Russian oil prompt Ukraine snub

How Russian oil companies build their “shadow” fleets

"Shadow" tankers are defined as vessels that operate outside the countries that implement the policy of limiting the price of Russian oil. These vessels do not need to comply with the oil price cap policy and can facilitate the transport of Russian oil at any oil price. The expression "shadow” tankers is used in a broad sense to define vessels that Russia can use to circumvent sanctions.

Stories about Russia's "shadow fleet" have become common in the media. However, as CREA's thorough analysis of the structure of Russian oil exports shows, there doesn’t appear to be a single entity operating a “shadow fleet”. These “shadow” tankers are used by individual oil traders or intermediaries. Although they are trying to attain more vessels registered and insured outside the countries of the sanctions coalition, it is proving difficult. In practice, some of these old second-hand tankers have reached the end of their service life and do not have internationally recognized marine protection and indemnity insurance.

Since introducing sanctions, old "shadow" tankers without proper insurance have been increasingly used to transport Russian oil products. Out of the entire pool of vessels transporting Russian oil that are classified as "shadow" tankers, 89% of voyages involved the transportation of Russian oil products. The transportation of Russian crude oil accounted for 72% of “shadow” tanker voyages through the end of July 2023 since December 2022, when the sanctions were implemented.

G7 still feeding Russia’s war machine with fossil fuel addiction

The Russian state-owned shipping company Sovcomflot controls only 30% of the “shadow” tankers. In contrast, the rest are controlled by a mass of opportunistic traders eager to make quick profits on Russian oil.

Identification and growth of "shadow" tankers

Before Russia invaded Ukraine, only 13% of the oil volume leaving Russian ports was transported by “shadow” tankers. However, as of July 2023, this figure has more than tripled to 42%. Since the start of the invasion, those vessels have been used at a greater pace - showing up in Russian ports much more frequently.

In 2021, 51 “shadow” tankers, each carrying volumes between 750,000 and 1 million barrels, were used to transport Russian crude oil. Their number doubled to 103 by the end of 2022. Another 43 were added in the first half of 2023. According to CREA, 146 "shadow" tankers were transporting Russian crude oil from January through July.

The number of smaller vessels transporting Russian oil products, with a volume of 150,000 to 200,000 barrels, has also increased, but less significantly: from 154 in 2021 to 223 in July 2023.

Why Russia is still making money on energy sales and how to change this

Nevertheless, more than half of Russian oil and oil products are still transported by tankers owned or insured by companies registered in the countries of the sanctions coalition.

Since the introduction of sanctions against Russian oil, 59% of crude oil vessels and 62% of oil product vessels leaving Russian ports have been insured in countries that implement price-capping policies.

Ship-to-ship transfers: method by which Russia skirts oil sanctions

Russia is trying to hire all available tankers from the global "shadow" fleet, including those that have been transporting Iranian oil. However, many third-party owners of “shadow” tankers seem reluctant to make their vessels available for trade with Russia on a permanent, exclusive basis.

In addition, many are not inclined to offer their vessels for lease under time charter agreements. They acknowledge the risk of their tankers being banned from entry to most of the key customer ports and eventually scrapped as useless if the United States and EU would really tighten the sanctions.

Since the sanctions on Russian oil came into effect in December 2022, the number of “shadow” tanker voyages increased by 82% to an average of 60 voyages per month by July 2023, and oil volume increased by 78% to 6.4 million tons per month.

LNG frenzy boosts Russian gas in Europe, not energy security – opinion

Despite Russia's efforts to attract the maximum number of "shadow" tankers and increase the frequency of their voyages, there is still insufficient capacity to transport most of the Russian oil destined for the world market. Ship-to-ship transfers that mask the origin of the oil are ways that traders are illegally enabling Russian oil onto global markets at high prices, helping to fund the war against Ukraine.

Due to insufficient “shadow” tanker capacity available to ship the majority of Russia’s oil, exporters rely on tankers owned and insured in countries implementing the oil price cap. During periods when prices are above the oil price cap, tankers owned and insured in countries implementing the policy are still transporting Russian oil.

These owners or insurers are therefore violating the policy by falsifying attestation documents that suggest the price is, in fact, paid below the $60 per barrel level required to facilitate Russia’s oil exports.

Aging "shadow" fleet carrying Russian oil poses disaster risk

Observation of ship-to-ship (STS) transfer operations in the Mediterranean Sea, conducted by Ukrainian volunteer analysts based on Marine Traffic data, revealed 33 STS operations and 66 vessels involved in the transshipment of Russian oil from 30 July to 23 September. Of these vessels, 52 are over 15 years old, and 43 do not have reliable Western P&I insurance.

Such activities are obviously fraught with the risk of oil spills and accidents with potentially catastrophic environmental consequences, but the EU has so far turned a blind eye. Risks are exacerbated by the fact that “shadow” tankers often turn off automatic identification systems (AIS) to conceal their movements and participate in STS operations.

At present, Russian oil is transported either:

- in compliance with international safety norms and standards and with P&I insurance—on tankers of the sanctions coalition countries,

- or without insurance and with huge risks.

Despite speculation, Russia has no real third alternative.

Since the "shadow" tankers are already practically engaged in transporting Russian oil products and crude oil, Russia has limited opportunities to increase further exports on vessels not subject to the price cap policy. Almost all of the old, worn-out tankers are already utilized.

In addition, there are limited opportunities to change the country of registration or insurance of a vessel to a country that is not subject to sanctions.

Trending Now

This underscores the importance of sanctions monitoring and enforcement by countries increasingly controlling most maritime transportation and insurance.

Logistics of Russian oil after sanctions and its bottlenecks

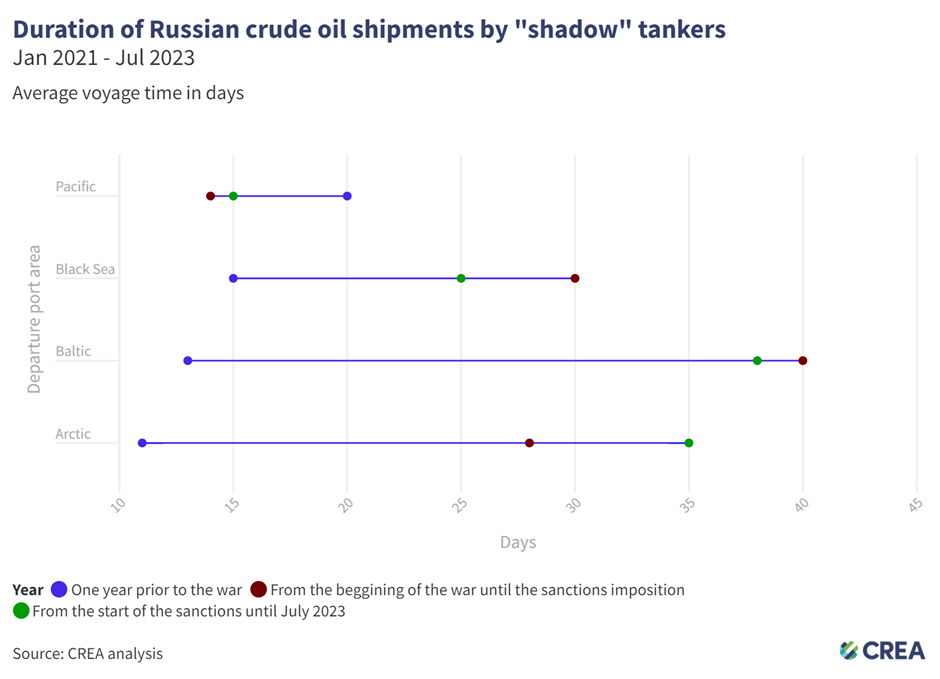

Before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the shortest delivery time for Russian oil was from Arctic ports to EU countries, with voyages lasting 11 days on average. After the invasion, the delivery time for oil from the Arctic to consumers increased to 28 days, and after the imposition of sanctions, to 35 days.

The invasion of Ukraine has further affected shipments from Russian ports in the Baltic Sea. Before the conflict, the average delivery time for oil from these ports was 13 days, but with the invasion, it increased to 40 days as flows were redirected from the EU to countries such as India.

In terms of Russian Black Sea ports, the delivery time before the invasion was, on average, 15 days, but after the invasion and after the sanctions, this period has grown to 30 and 25 days, respectively.

The increase in the time for Russian oil deliveries is mainly due to the reorientation to Asian markets, especially India, China, Türkiye, the United Arab Emirates, and Singapore, due to the EU embargo and the G7 price cap.

A significant amount of Russian oil is transported from ports in the Baltic and Pacific regions. These two regions account for the largest Russian crude oil transportation market share using “shadow” tankers. Between December 2022 and July 2023, “shadow” tankers transported about 23 million tons of crude oil from Russia's Pacific ports, while the Baltic Sea ports delivered 21 million tons.

From the Far Eastern port of Kozmino, Eastern Siberia–Pacific Ocean oil pipeline crude is exported to China at prices above the price cap. More than 95% of exports from this port were sold at prices above $60 per barrel in the first quarter of 2023. In flagrant violation of the sanctions, tankers owned by individuals or entities from countries within the sanctions coalition, or those with outdated P&I insurance, persist in transporting Russian oil from Kozmino without adhering to the price cap.

Following the imposition of sanctions on Russian oil, its delivery logistics schemes have grown increasingly intricate. Oil trade routes have undergone significant changes. Most oil products transported by “shadow” tankers are moved from ship to ship in inland waters because the ships avoid direct entry to Russian ports.

In total, 29% of these oil products were sent to Türkiye on “shadow” tankers, 8% to China and 6% to Brazil. Additionally, a further 9% of the total oil product volume was dispatched to the territorial waters of the price cap coalition countries, where these shipments performed ship-to-ship transfers, typically involving tugboats and other shore services. This diversity of destinations indicates the evolution and complexity of the Russian oil trade due to sanctions.

Tankers carrying Russian oil may also face delays in critical passages such as the Bosporus, Suez Canal, and the Danish Straits, as the trade of sanctioned Russian oil has changed significantly.

What should the West do to reduce the flow of Russian petrodollars significantly?

Ukraine's allies should do more to deprive Putin of the ability to finance the war against Ukraine by fully monitoring and enforcing sanctions.

Curb the "shadow" fleet's growth by restricting the sales of tankers

An increase in the number of "shadow" tankers can be prevented by not allowing the sale of tankers to owners that are not registered in countries implementing the oil price cap policy.

Experts also recommend that all insurance and other services be banned for vessels that fall under the following three conditions:

- the vessel is transporting Russian crude oil or oil products;

- the vessel's owner or management company changed after 24 February 2022;

- the ship owner has not confirmed that the source of funds for the purchase has no connection to Russia.

Restrict passage of "shadow" tankers by requiring Western insurance

The states within the sanctions coalition also have the authority to restrict the passage of "shadow" tankers through their territorial waters. They reserve this privilege exclusively for vessels that transport Russian oil in accordance with the price cap limit and that possess dependable insurance.

To achieve this, establishing compulsory P&I insurance requirements from Western insurance firms as a prerequisite for transiting, for example, the Danish Straits in the Baltic, and other critical sea routes passing through the territorial waters of sanctions coalition nations. A comparable condition to gain access to their ports could also be enforced.

Monitor and strengthen sanctions policy

United States and UK officials are currently making statements about the need to revise the sanctions policy on Russian oil, as the G7 price cap is no longer effective and Russian oil is being sold at prices well above $60 per barrel.

To reduce the risk of abuse and the circumvention of price cap restrictions, it is crucial to intensify monitoring and enforcement of the sanctions policy.

Measures should also be implemented to strengthen sanctions against individuals or entities engaged in financing and facilitating Russian oil exports.

Effective enforcement will require cooperation among national-level entities, including other G7 members.

Strengthen penalties for oil price cap violation

The penalties for violation of the price cap must be strengthened. Current penalties provide for a 90-day ban of vessels from securing maritime services after violating the price cap, a mere slap on the wrist and one that is not utilized. Vessels should be fined and banned in perpetuity if they are found guilty of violating sanctions.

The price cap coalition should also strengthen legislation on the oil price cap to include the banking and financial sectors. Monitoring, for example, of bank processes that would detect if a payment is part of a transaction that exceeds the price cap, and, if so, is punished as a violation.

After these fundamental conditions are fulfilled and Russia's capacity to utilize “shadow” tankers is thwarted, the G7 countries can exert stricter control over Russian oil exports by instituting periodic price cap assessments. This aligns with the commitment made in December 2022 when member countries agreed to establish price caps on Russian oil and oil products and pledged to conduct reviews every two months. This is a process that has now been abandoned, effectively leaving member countries with blood on their hands as their funds continue to flow into Putin’s war chest financing war crimes in Ukraine.

Edited by Mike Cronin

Isaac Levі is CREA's Europe-Russia Policy & Energy Analysis Team Lead.

Oleh Savytskyi is Razom We Stand's Campaign Manager.

Oleh Savytskyi is Razom We Stand's Campaign Manager.Related:

- G20 host India & member states’ addiction to Russian oil prompt Ukraine snub

- Russia circumvents oil sanctions, outsmarting the West

- Russian Black Sea oil exports reached a new record in March, with tankers going to Asia

- G-7 nations consider outright ban on exports to Russia, Bloomberg says

- Shell continues trading Russian gas despite pledge to withdraw