Ukraine is investigating who is responsible for Russia's blitzkrieg occupation of southern Ukraine in the first months of the war.

The State Bureau of Investigations (DBR) is probing possible leadership failures within the Southern forces commanded by Generals Serhiy Naiev and Andriy Sokolov. The investigation aims to determine whether they missed signs of Russia's impending attack and inadequately prepared their troops and defenses.

As the investigation unfolds, official findings remain undisclosed, leaving room for speculation and manipulation.

Earlier, the Ukrainian media Ukrainska Pravda (UP) interviewed key military figures, including former Commander of the Ukraine’s Southern forces, Major General Andriy Sokolov, and marine Ivan Sestryvatovsky, who was assigned to destroy a bridge in Chonhar but faced challenges. These interviews were conducted by Sonia Lukashova, Sevgil Musaieva, and Yevhen Buderatskyi. Journalists have used this information to construct a detailed timeline of the events, which we summarize for you.

Three paths out of Crimea

Occupied Crimea has three routes connecting it to mainland Ukraine: the checkpoints “Kalanchak” and “Chaplynka” leading to Kherson, a regional center, and Nova Kakhovka, as well as the Chonhar Isthmus to Melitopol.

Three bridges along the Chonhar route were rigged with explosives after Crimea's occupation, ready to be detonated in case of a Russian invasion. Preparations were also made to disable bridges in Henichesk and four dams along the Crimea border.

According to the Ukrainian military, most of these facilities remained mined until the 2022 invasion, except for two remote Kherson region bridges, over the Kakhovka and North Crimean Canals, which were cleared of mines before 2018 due to insufficient military personnel for monitoring.

"Over time, the number of troops decreased because they were needed in the Joint Forces Operation area [in the Donbas region]. Leaving a mined bridge unguarded in a peaceful area was not a viable option," explained Sokolov.

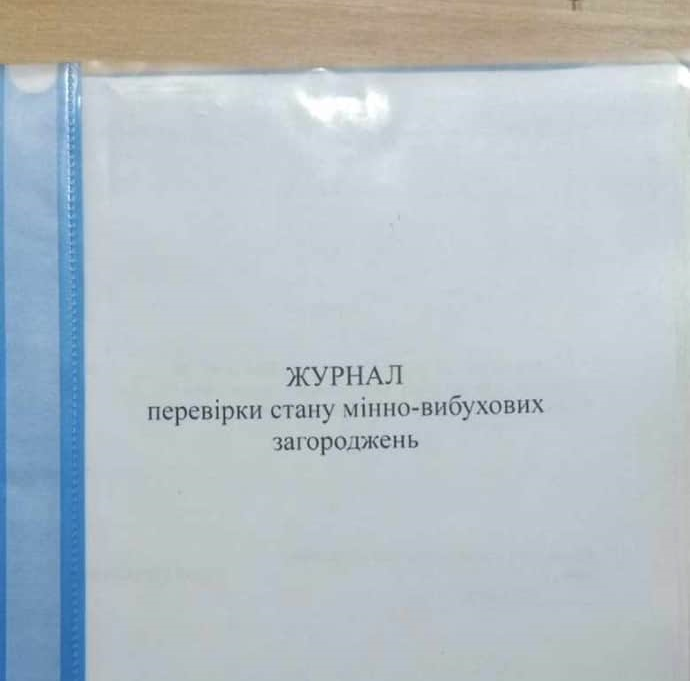

Just beyond the bridges, Ukrainian military personnel set up five minefields, subject to bi-monthly inspections.

"Furthermore, there is a record of these inspections. For some reason, they are silent about it. However, it still exists," notes the interviewee from the Joint Forces Command.

The journal documented inspection dates, complete with the names and signatures of those overseeing the checks. Remarkably, sappers encountered no faults or issues throughout the observation period.

The Russians knew about the locations of minefields, as everyone in the region did. It couldn’t be otherwise – to protect civilians from mine explosions, warnings were prominently displayed everywhere.

On the brink of invasion

In February 2021, a year before the invasion, sappers added anti-tank mines and later replaced detonators on all mines by autumn 2021.

Two units, the 59th Brigade and the 137th Marine Infantry Battalion, were deployed to the Southern grouping, which operated on a rotating basis. Major General Andriy Sokolov assumed command and approved two action plans, one for peacetime stabilization and another for defense during escalations.

Sokolov was supposed to receive two brigades (each with 3-5 thousand personnel) and a battalion (500 personnel), with two territorial defense brigades for reinforcement in combat.

However, in practice, the Southern grouping was never fully staffed, even during peacetime. The second brigade was never assigned, and existing units were only partially formed.

As a result, Sokolov had approximately 1,600 military personnel, with 1,300 in the 59th Brigade and 300 in the 137th Battalion, when the invasion began. The Russians invaded southern Ukraine with a force of 20,000 personnel.

“[Russia]concentrated its forces along a large stretch from Belarus to Crimea. We did not have enough forces, as we needed to keep troops in the Joint Forces Operation area [in the Donbas region], cover Kyiv, cover the north, Slobozhanshchyna [Northeast Ukraine], the Kharkiv direction,” the general stated.

The Defense Perimeter

The 137th Battalion's marines guarded three key points on the border with occupied Crimea. Their main weapon was a 120mm mortar. The 59th Brigade, initially stationed near Mykolaiv, relocated to the Oleshkivski Pisky training ground in Kherson Oblast just 10 days before the invasion.

Russian foreknowledge of Ukraine's defense line was confirmed through captured maps and staff documents.

On 14 January, General Sokolov held a briefing with commanders, police, border guards, and Ihor Sadokhin, the head of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) Anti-Terrorism Center, clarifying coordination and tasks for southern defense. A month later, sappers conducted a final minefield inspection.

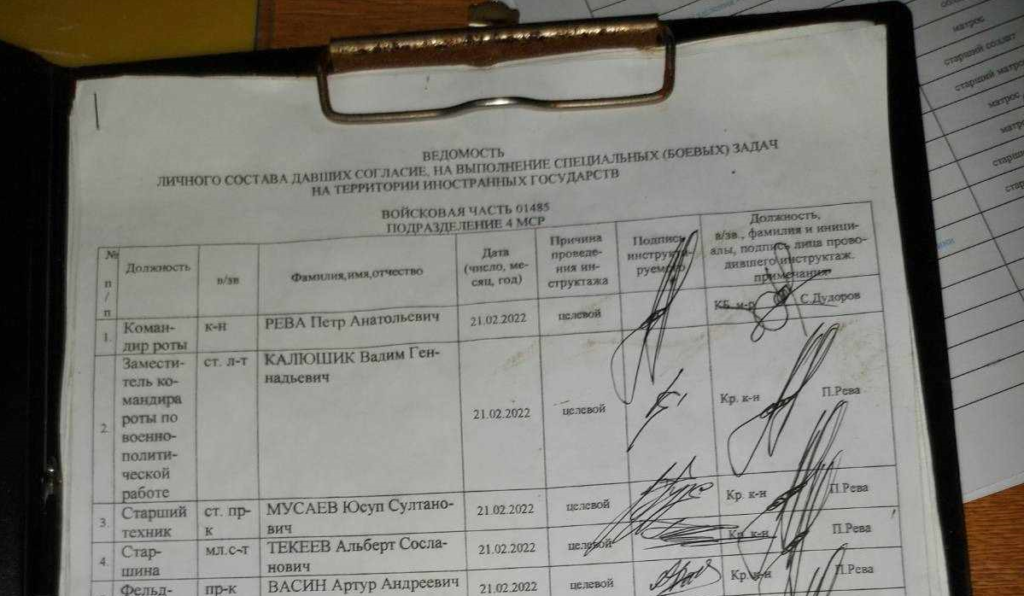

By 21 February, one of the Russian brigades stationed in occupied Crimea shared a detailed attack plan with its troops. This brigade had authorization for foreign combat operations.

Within five days of the invasion, Russian forces planned to advance through Mykolaiv, execute an airborne landing near Odesa on the ninth day, seize Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi, and reach the Moldovan border by the 11th day to establish their positions.

23 February 2022

On the eve of the invasion, the Russians abruptly halted cross-border movement in Crimea and initiated demining operations near border crossings. Ukrainian marines reported it to their command. The response was to increase vigilance.

Simultaneously, Sokolov ordered the 59th Brigade to assume defensive positions, but the deployment time was set for 6 AM on 25 February, causing delays.

On the night of 23-24 February, Ukrainian marine Ivan Sestryvatovskyi, stationed at Chonhar, prepared two vehicle bridges for demolition around 3 AM. Although not a trained sapper, he had basic knowledge of detonator use, and the process was straightforward.

“There's a device in which you insert two wires, charge the detonator, and turn the device until the light bulb ignites,” explained the sappers.

In the critical hours preceding the invasion, General Sokolov monitored the skies above Crimea from his headquarters.

“We counted them and lost track around the 30th plane,” he said.

Trending Now

On the same day, Sadokhin, the head of the SBU Anti-Terrorism Center, confidently asserted in a closed meeting at the Kherson Regional State Administration that there would be no invasion. Months later, he faced criminal charges and detention.

24 February 2022

At 3:50 AM, Russian artillery struck the occupied territory near the Ukrainian border crossing at Chaplynka. This initially raised suspicions of provocation among the Ukrainian military, but it was later discovered that the Russians were actually using the artillery to clear Ukrainian minefields.

"If during a mortar attack or artillery bombardment debris hits the power grid, it gets damaged, and then it won't initiate an explosion," one of the sappers explained.

At 5:00 AM, Russia initiated a full-scale invasion, with aircraft previously over Crimea launching extensive missile attacks on mainland Ukraine.

Ivan Sestryvatovskyi, stationed at his post, awaited orders to detonate the bridges. However, radio communication abruptly ceased, forcing Ukrainian military personnel to switch to WhatsApp for communication.

"If communication fails, then those responsible must blow up the bridges on their own," explained former commander of the 137th Battalion Vadym Rymarenko.

So, Sestryvatovskyi attempted to blow up the bridges.

"But there was no explosion… I attempted to reconnect the wires, thinking there must have been a mistake, a faulty connection somewhere. I tried reconnecting and repeated the process three times, but there was no explosion," recounted the marine.

Other Ukrainian soldiers successfully demolished three of the four dams along the Crimean border and partially detonated a bridge near Chaplynka. The explosive device on the railway bridge at Chonhar worked but caused limited damage.

In a heroic act, soldier Vitaliy Skakun sacrificed his life to blow up a bridge in Henichesk, posthumously earning the title of Hero of Ukraine. Notably, this bridge wasn't initially mined; instead, two explosive-laden trucks were strategically placed nearby. The plan involved driving these trucks onto the bridge, connecting the wires, stepping back to a safe distance, and initiating the explosion. Skakun executed each step flawlessly, except for his own escape.

At 6:00 AM, the Russians initiated a ground offensive towards Kherson and Melitopol. The 59th Brigade, unable to reach the main defensive line, engaged in combat across various areas in the Kherson Oblast, sustaining losses.

"The balance of forces and resources was 1 to 15, maybe even 1 to 20," explained Commander of the 59th Brigade, Oleksandr Vynohradov.

By 7:05 AM, marines on the Crimea border were ordered to retreat as Russian forces had breached their defenses, encircling them. They withdrew toward Kherson and Melitopol, with sappers discreetly leaving in civilian buses amidst the Russian column.

"The Russians probably didn't realize we were the enemy. It was all so confusing. We just quietly left in the middle of their column," one of the sappers recounted.

Around noon, twenty Russian helicopters landed on the Antonivskyi Bridge over the Dnipro River in Kherson city, blocking the land route for Ukrainian military and civilians. Another route, the Kakhovka Bridge further upstream was also seized.

"There were so many civilians fleeing the Russians from the south, from towns like Hola Prystan, Chulakivka and Kalanchak. But the enemy's paratrooper units wouldn't let anyone pass and shot them point blank in the forehead," recalls Vynohradov.

Possibly, these bridges weren't pre-mined to ensure the routes of retreat remained open. However, General Sokolov maintains that defending the Dnipro was not within his mission scope.

"The Dnipro River is strategically vital. There should have been a dedicated defense line, with another military formation responsible for it. Relying on our forces to both hold off the enemy in Kherson and prevent them from crossing the Dnipro is, to put it mildly, a mistake," Sokolov emphasized.

The 59th Brigade successfully broke out of the encirclement and reached the west (right) bank of the Dnipro, and commanders Dmytro Dozirchyi and Yevhen Palchenko were honored as Heroes of Ukraine.

Mobilization orders for the Kherson territorial defense were only received at 14:00 on 24 February, by which point they had approximately 200 personnel.

Meanwhile, the Southern forces' command shifted operations to Zaporizhzhia Oblast, moving away from their original retreat towards Melitopol.

"On the evening of 24 February, we were given additional forces. This was a regiment of the National Guard, a patrol guarding public order, and the 110th Territorial Defense Brigade from Zaporizhzhia," recalls Sokolov.

The Russians were standing on the outskirts of Melitopol, but the Ukrainians went in there and tried to take control of the city. However, there were not enough forces.

In both retreat directions, the Kherson forces, having met with reinforcements, continued the fight for Ukraine.

Allegations

Allegations of demining have deeply concerned all the military personnel interviewed by UP. They consider these accusations groundless.

However, their primary concern is the attempt to shift full responsibility onto them. Despite clear signs of an impending Russian invasion, Ukrainian authorities downplayed the threat. Consequently, the ongoing DBR probe is viewed as a potential way to exert pressure on them.

Read more: