In violation of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU and Association Agreement with Ukraine, four EU countries, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, and Bulgaria, have banned the import of all agricultural products from Ukraine in April. Following their blackmail, the European Commission found a so-called "compromise" solution to temporarily ban the import of wheat, corn, rapeseed, and sunflower seeds from Ukraine to these four countries and Romania starting from 2 May 2023.

However, there is no legal framework behind this decision. Instead, a dangerous precedent of individual EU countries blackmailing the entire union questions the strength of EU regulations in the future. The ban has significantly hindered Ukraine’s economy, which is already damaged by war. The situation was further exacerbated by new import tariffs imposed by key importer Türkiye and by Russia’s sabotage of the UN-brokered grain corridor.

An unexpected ban on Ukrainian imports by EU countries blocks more than 14% of all Ukrainian agricultural exports, critical to maintaining the trade balance amid Russia's war

Following Russia’s full-scale aggression in 2022, Ukraine’s GDP shrank by 29.1%. The EU initially provided significant economic aid by allowing the transit of Ukrainian exports through their territories and canceling EU tariffs on trade with Ukraine. However, the unilateral decision of Poland to ban imports from Ukraine, shortly after the meeting between Ukrainian and Polish presidents on 5 April 2023, became a significant blow to the Ukrainian economy. This became especially true after Hungary, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and partially Romania joined the ban after 15 April 2023.

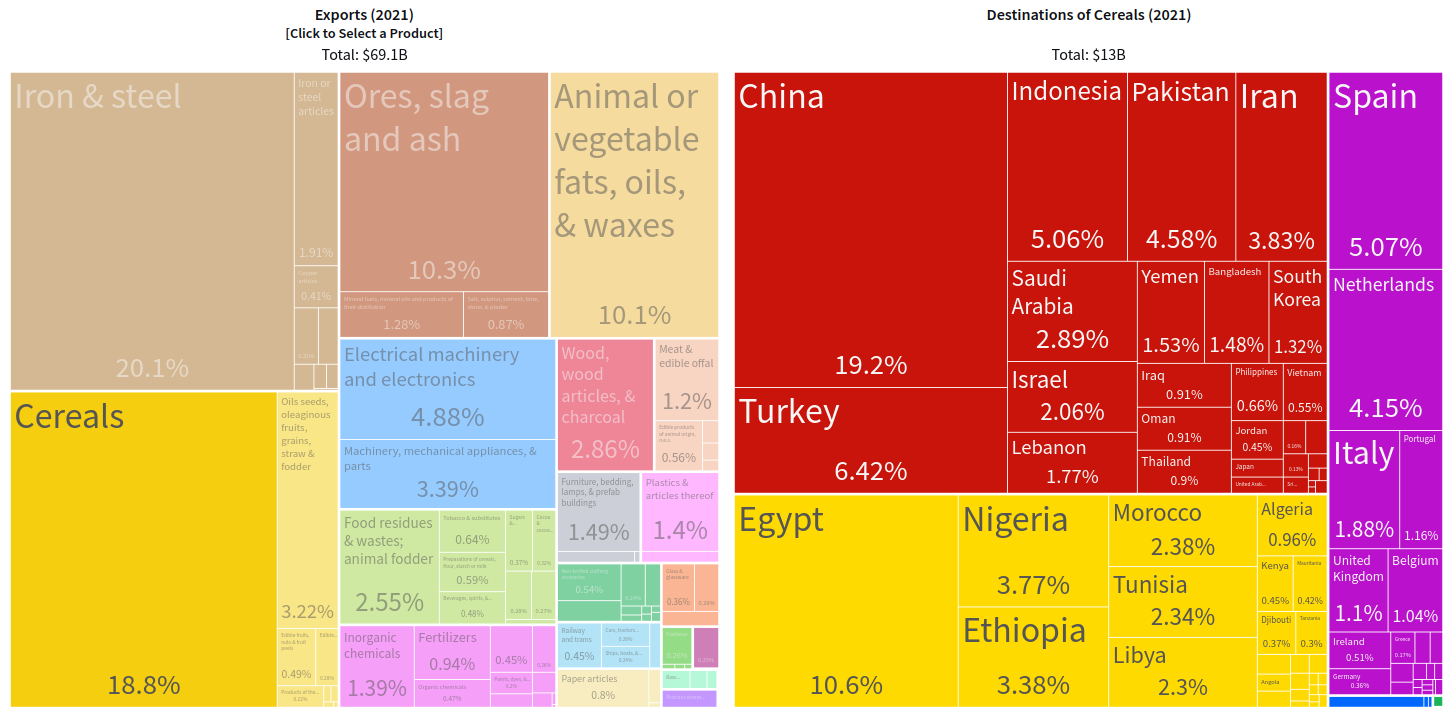

Before the full-scale Russian invasion in 2022, most of Ukraine's cereal exports were destined for Asian and African countries. However, due to the Russian blockade of Black Sea ports, a large portion of Ukrainian cereals could not be delivered to their intended destinations in Asia and Africa. Consequently, exports were partially redirected through the EU, with transit through Romanian and Polish ports playing a crucial role in maintaining trade.

According to Ukrainian MP and head of the Parliamentary Committee on Taxation Policy, Danylo Hetmantsev, the ban on the import of agricultural products by Poland and Hungary will block nearly 14% of all Ukrainian agricultural exports.

He provides figures for the first quarter of 2023, saying that the export of agricultural products from Ukraine to all countries of the world amounted to $6.75 billion. Export of agricultural products to Poland during this period amounted to $652 million, and to Hungary – $268 million. That is, these two countries alone accounted for 14% of all Ukrainian agricultural exports in the first quarter of 2023, which has since been stopped due to the embargo.

Losses in exports would be greater if other border countries joined the ban, including Romania. In 2022, Romania, after Poland, became the second-greatest exporter of Ukrainian agricultural products and the first in terms of grain exports. The country itself imported 15% of all exported Ukrainian grain.

“Ukraine will suffer significant losses due to the embargo on the export of its agricultural products to neighboring EU countries,” Hetmantsev said. “The answer to the question of which country's agriculture in the region is currently suffering colossal losses due to Russian aggression is obvious. Equally obvious is the need to resolve trade disputes, taking into account the spirit of strategic partnership and existing agreements, primarily at the EU level, the strength of which as a union lies its e implementation of a single coordinated trade policy.”

Poland's blackmail of the EU

Importantly, the initial ban introduced by Poland applied not only to cereals, which Ukraine produces massively. It also applied to products such as wine or milk, which are exported from Ukraine in small quantities, benefiting only several small enterprises. For example, in the first quarter of 2023, Poland imported milk products worth $4.8 million from Ukraine, but its exports of milk products to Ukraine amounted to $24.7 million. That is, Poland exported five times more (!) milk products to Ukraine than it imported from Ukraine. Nevertheless, it decided to include milk products in the list of 18 categories of banned imports from Ukraine.

Poland openly recognized that this ban was essentially blackmail of the European Commission, saying it would stay until the Commission bans several Ukrainian imports. According to the EU agreements, only the European Commission, and not a single EU member state, can impose trade limits.

At the end of April 2023, following the three rounds of negotiations between the European Commission and Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, and Bulgaria, a so-called compromise decision was reached that the Commission bans the import of four categories of products, namely wheat, corn, rapeseed, and sunflower seeds. Other imports were unblocked. Simultaneously, the commission prolonged its previous decision on tariffs-free trade with Ukraine regarding all other categories of products.

The ban introduced by European Commission is expected to last until 5 June 2023, although Poland demands to prolong it for the entire year 2023. While the damage to the Ukrainian economy was partially reduced, Ukraine still protested against the decision, saying it violates the existing Association Agreement with the EU.

Is Ukrainian grain “guilty,” as Polish farmers claim?

Farmers in Poland have been protesting since September 2022, saying that imports of Ukrainian cereals have flooded the market and dropped prices.

"We do not object to Ukrainian grain being transported through Poland. But Minister [of Agriculture] Kovalchyk said in May and summer that this grain would not be unloaded here, that Poland would only be a transit country. And it turns out that 80% is sold here... We see a big drop in grain prices, and Polish farmers have no way to profitably sell theirs," said the leader of the Polish AgroUnia association, Michal Kolodzejczak.

However, a Polish market analyst, Mirosław Marciniak, writes that the grain price has decreased in Poland not because of the inflow of Ukrainian grain but because of the global decline in price. Polish farmers were reluctant to sell grain when its price peaked in Autumn 2022 and instead waited in hopes that it would increase even more.

Marciniak also notes that the Polish ban on imports from Ukraine is a populist decision, given that it includes products that were imported from Ukraine before the war and whose volume of imports didn’t increase. The ban is most likely related to the elections in Poland scheduled for Autumn 2023 rather than the real market situation.

Denys Mararenko, head of the international trading department at one of Ukraine’s big companies, Agrosem, writes that it is a myth that the Polish market is allegedly overloaded with Ukrainian cereals. He says his company sells 95% of its products directly to Polish ports, having little impact on the internal Polish market. There is enough free capacity in the Polish ports to export cereals if Polish farmers sold it to traders, according to Mararenko.

The general director of another big Ukrainian trader UGTC Trade Ihor Vovchenko says that there was the practice of selling Ukrainian cereals to Polish intermediary companies, which, however, still would re-export it further.

Now, a ban on imports from Ukraine to Poland means this practice of re-exporting will not be possible anymore, and his company will lose 70-80% of its export potential until other ways to export are found.

“Commercial Polish companies cleared our grain customs and sold it to Polish port traders. Then they would re-export it further. This is transit, although legally the goods were cleared by customs on the territory of Poland and exported from Polish ports. Now this option is lost for us. Most of the engagements we established over the past year, working with commercial Polish companies, have been put on hold. For us, the loss of cooperation with commercial Polish companies is a loss of 70-80% of export potential [through the EU].”

The unilateral ban introduced by Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, and Bulgaria violates international agreements

The unilateral ban violates the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU and the Association Agreement between Ukraine and the EU.

Poland’s ban on the import of Ukrainian goods into its territory, an integral part of the EU internal market, is a direct violation of the Association Agreement between Ukraine and the EU, in particular Article 35, establishing the inadmissibility of introducing quantitative restrictions or bans on the import of goods. The Association Agreement defines specific quotas and tariffs for several types of goods, but they are established solely on the EU level. Individual EU states can’t introduce them, and a total ban on the import of goods can’t be introduced at all.

Finally, the Polish Ministry's decision is incompatible with EU legislation, namely with the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (Article 28 (2) and Article 29).

These articles guarantee the free circulation of goods within the EU Customs Union (of which Poland is a part) after compliance with all necessary customs clearance formalities. The EU Treaty directly and unequivocally gives goods originating from third countries (i.e.Ukraine), after a customs clearance when being imported into the customs territory of the EU, the same status as goods of European origin. This very norm demonstrates the absurdity of any attempts by Poland to divide the import and transit of Ukrainian goods to other EU countries, as the EU Customs Union does not allow the existence of separate national customs territories. Legally, the option to merely “transit” grain through Poland to Germany without allowing it to be sold in Poland doesn’t exist within the EU, writes Nazar Bobytskyi, an expert on international trade.

For the same reason, the decision of the European Commission to ban Ukrainian imports to five EU countries and allow it to others contradicts the EU Agreement and creates a dangerous precedent of internal trade divisions within the EU. Nonetheless, the Polish strategy of blackmail has worked, at least partially, questioning the further authority of the EU legal regulations.

The situation gets even more difficult for Ukraine with Russia sabotaging the “grain corridor” and Türkiye introducing 130% tariffs

After the full-scale Russian invasion, when Ukrainian agricultural exports were forced to redirect through neighboring or close countries, Türkiye became the largest buyer of Ukrainian wheat and barley. According to the Ukrainian State Customs Service, in the first quarter of 2023, Türkiye imported 17.7% of exported Ukrainian wheat, worth $168.8 million. Türkiye also imported 42.1% of all barley exports, worth $52.7.

The Turkish government has decided to introduce an import tariff on wheat, barley, and corn from 1 May 2023. The tariff rate will be 130% instead of the current 0%. This measure, entirely legal and aimed at protecting domestic producers on the eve of the new season, will also negatively affect the Ukrainian economy.

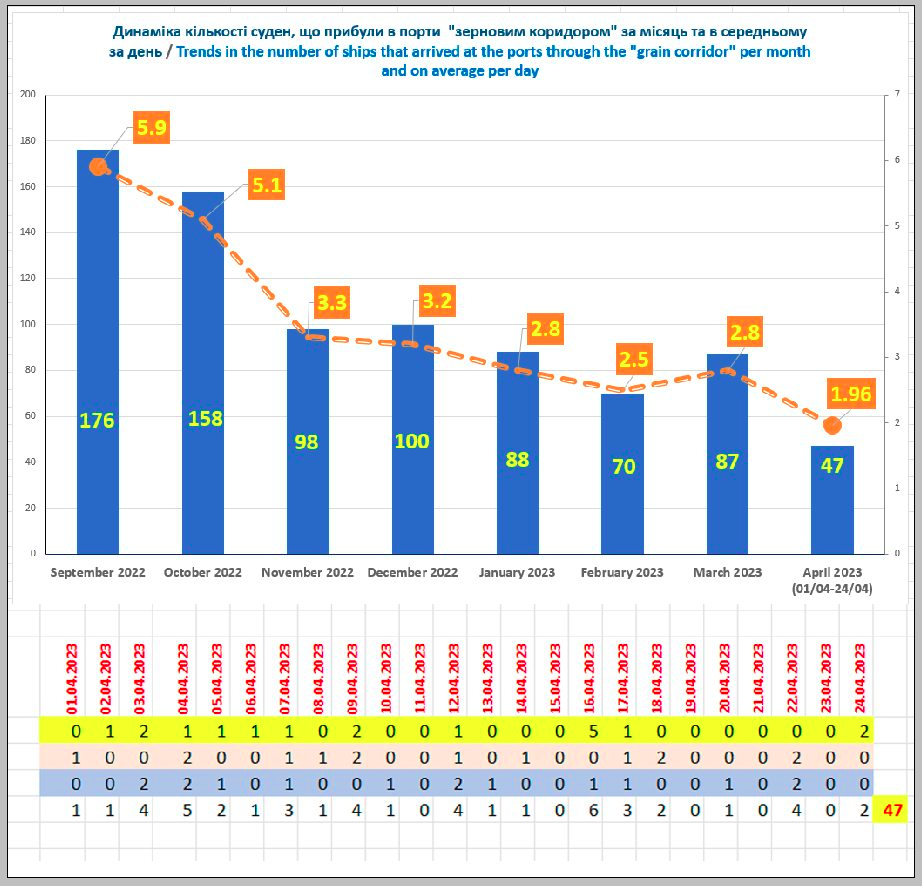

Yet, the most problematic is the situation with the Ukrainian Black Sea “grain corridor,” allowing the export of grain and corn through the Ukrainian port city of Odesa in an UN-brokered agreement. Russia has the right to inspect ships according to the agreement, and in recent months, it has widely used this as an opportunity to sabotage the corridor. Under various pretexts such as holidays, broken boats to arrive on ships, or document mistakes, Russians have slowed down inspections.

In Istanbul, inspections of cargo vessels as part of the Black Sea Grain Initiative have not been carried out for two days, the representative of the UN Secretary-General Stéphane Dujarric said on 25 April. Since April 14, the Russians, without any explanation, have refused to register three vessels for which cargo is waiting at a Ukrainian port.

Currently, more than 50 ships are waiting in the Bosphorus Strait for permission to go to Ukrainian ports to load grain. According to the Ukrainian Black Sea Monitoring Group, the capacity of the grain corridor has gradually decreased from 176 ships in September 2022 to 87 ships in March 2023 due to Russian sabotage of its agreement with the UN.

To solve the crisis, it is necessary to unblock the export of Ukrainian products to and through the EU, especially given the ban's illegal nature, Ukraine's Association Agreement with the EU, and candidate status for membership. Negotiations between five EU countries, the European Commission and Ukraine are ongoing.

"There is quite a lot of intensive work with the involvement of representatives of these countries, Ukraine and the European Commission, because, after all, we must remember that these countries are members of the EU, where there are unambiguous rules regarding trade, including foreign trade, and they should be the same for all EU members," said Deputy Minister of Agriculture Policy of Ukraine Taras Vysotskyi.

If not removed, the current blockade contradicting the EU agreements and Association Agreement with Ukraine would loosen the legal basis of the EU and its unity in the face of continuing Russian aggression.

Read also: