All countries have mafia — but the Russian mafia has a country, a joke goes.

Evgeny (Yevgeniy) Prigozhin, known as “Putin’s chef,” started his business career in the 80s, in a Soviet prison, serving a decade of hard labor for theft, fraud, and robbery. In the 90s, he got involved in organized crime in St. Petersburg and managed a gambling business supervised by Putin. In the early 2000s, he made millions of dollars receiving exclusive state orders for catering, maintenance, and construction from the Kremlin and the Ministry of Defense.

He built his own empire within Putin’s empire. Prigozhin serves the Kremlin’s interests by sponsoring mercenary groups that are led and staffed by known neo-Nazis and convicted criminals. Illegal in Russia in the past, these private military groups were openly supported by the Kremlin as they carried out military operations in Ukraine and Syria.

In Syria, companies associated with Prigozhin receive 25% of oil and gas money generated in the territories they reclaim for Assad. As a result of the above activities, Prigozhin was sanctioned by the US and EU as a person close to Putin and has been put on the FBI wanted list in February 2022.

In an interview with Austria’s ORF television, Putin compared Prigozhin to George Soros, claiming that the latter “intervenes in things all over the world.”

“'But the State Department will tell you that it has nothing to do with that, that this is the personal business of Mr. Soros… Well for us, this is the personal business of Mr. Prigozhin,' Putin said. ‘There’s your answer. Does that response satisfy you?’ Putin, smiling, asked.”

Anyone familiar with life in Putin’s Russia understands that there is no such thing as “personal business” there. “Money laundering is a serious crime. When a head of state is a money launderer, America must take it seriously,” said Preet Bharara, a former US attorney, fired by Trump.

Mafia state

In the 1990s, the USSR collapsed.

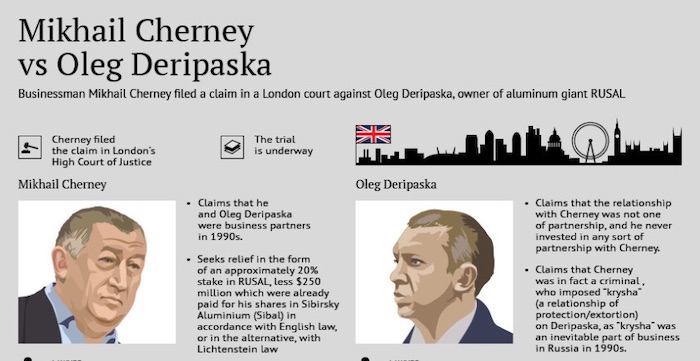

Private businesses popped up like mushrooms and generated big money. Meanwhile, the KGB officers, Soviet military, Communist party leaders, "Red directors" (heads of big enterprises in the Soviet Union), and elite athletes lost their jobs, income, and power. The unemployed servicemen and demoralized athletes joined convicted criminals and formed militarized brigades. The gangs extorted money from entrepreneurs. The protection fees and the "protectors" shared a name: “krysha” (“roof.”)

Reluctance to pay “krysha” led to torture, kidnapping of family members, or murder.

Instead of busting racketeering, the impoverished security and law enforcement structures joined the racketeers, often in exchange for compensation. Law enforcement formed “a roof” for organized crime. The local government joined in for its share and became the “roof” protecting both organized crime and law enforcement.

The businessmen were paying the bandits and police; the bandits and police paid the government.

A businessman could not call the police on bandits: the police and bandits were the same. The bandits paid to be elected to be mayors and governors. They appointed judges and prosecutors. Lawlessness ruled. It was called “bespredel” (“limitlessness.")

By the end of the 90s, the bandits, the KGB/FSB, and the government fused into a conglomerate, glued together by crime, mutual liability, and mutual interests. The difference between the criminals, police, and authorities was no more.

Through the privatization and capture of public resources, this group came into possession of all natural resources in Russia and developed unprecedented wealth. Former bandits, KGB officers, and Communists became respected businessmen, “oligarchs.”

There was a lot of infighting. Thousands were killed in turf wars. Survivors formed Putin's syndicate that came to power in 1999.

Putin and Bandit St. Petersburg

In the 1990s, in St. Petersburg, nicknamed "a bandit capital of Russia," killing journalists and opposition members and poisoning eyewitnesses became a regular practice. Non-verbal messages such as dead animal parts by the entrance doors were common.

Wagner's Grey Zone publishes commentary alongside a photo of a sledgehammer put into a musician's briefcase that will be allegedly sent to the European Parliament as an "information case". This is a response to the EP calling to recognise Wagner as a terrorist organisation. pic.twitter.com/sY7XzQJNvF

— Dmitri (@wartranslated) November 23, 2022

“The group around Putin today is the same as the one that brought him to power from St. Petersburg in the 1990s,” wrote celebrated author Karen Dawisha in her book Putin’s Kleptocracy.

“In the 1990s, everything was up for grabs, and the new vory (thieves) reached out with both hands," writes Mark Galeotti, a senior researcher at the Institute of International Relations Prague and head of its Centre for European Security, a leading Western expert on the Russian organized crime.

"State assets were privatized, businesses forced to pay for protection, and as the iron curtain fell, Russian gangsters crashed out into the rest of the world. The vory were part of a way of life that, in its own way, was a reflection of the changes Russia went through in the 20th century. Organized crime truly began to come into its own in a Russia that itself was becoming more organized. Since the restoration of central authority under President Vladimir Putin…, the new vory have adapted again, taking a lower profile, and even working for the state when they must.

The challenge posed by Russian organized crime is a formidable one — and not just at home. Across the world, it trafficks drugs and people, arms insurgents and gangsters, and peddles every type of criminal service, from money laundering to computer hacking. For all that, much of the rest of the world remains willing — indeed, often delighted — to launder these gangsters’ cash and sell them expensive penthouse apartments.”

Over the course of the next 20 years, the mafia state turned into a mafia empire, with ambitions to expand in the US and UK, in Europe and Africa. Using the money from the privatized oil, gas, and natural resources industries, the KGB methods of physical extermination of opposition, and brainwashing to subvert the “Western world order,” the mafia state is attempting to take over the world.

Prigozhin, "Putin's chef": the very start

Evgeny “Zhenya” Prigozhin was born in Leningrad (currently St. Petersburg) in 1961 and, like most people in Putin’s close circles, got involved in sports at an early age. He attended a special sports boarding school for future athletes, specializing in skiing. At eighteen, he was sentenced to two and a half years of probation for theft and was sent to serve his term outside of Leningrad.

An article in a Russian publication Rosbalt, "The Stormy Youth of the “Kremlin Restaurateur,” sums up Prigozhin’s early career: thefts, fraud, and assault. The report is based on court documents and eyewitness accounts.

In 1980, Prigozhin — then 19 — returned to Leningrad without finishing his probation. Together with other young men, Prigozhin robbed apartments. The long list of stolen items includes vases, napkin holders, wine glasses, vodka shot glasses, tape recorders, crystal, a jeans jacket, a woman’s purse with makeup, hallway rugs, pens, and two horns.

In addition to multiple thefts, Prigozhin and a group of friends committed fraud by offering to sell Western-made jeans and other clothes unavailable in stores in the USSR and stealing the money without delivering the goods. Another crime committed by Prigozhin was an assault on a young woman for the purpose of stealing her coat, earrings, and boots. According to an accomplice, Prigozhin tried to strangle the victim and took off her earrings. The group was arrested. Prigozhin was sentenced to thirteen years of hard labor and confiscation of property for theft, fraud, the involvement of a minor in criminal activities (prostitution), and robbery. Prigozhin served only nine years of this sentence.

In 1997, Prigozhin returned to St. Petersburg and opened a luxury boat restaurant New Island. Putin frequented the boat and had a few important meetings there, including a dinner with the President of France Jacques Chirac in 2001, a dinner with the US President Bush in 2002 as well as his own birthday party in 2003.

In August 2004, according to an investigation by TSURrrealism and previous reports, Prigozhin beat up a young man on board the “New Island.” As a result of this beating, the young man fell into the river and drowned. Later, the crew was intimidated by Prigozhin and his security team, “current and former employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs.” The crew then helped to conceal the crime.

Prigozhin and Putin: Casinos and organized crime groups

According to an article in Novaya Gazeta, before coming to the restaurant business, Prigozhin managed a gambling business in St. Petersburg in the 1990s at the time when Putin served as the chairman of the casino and gambling supervisory council of the city. Licenses for gambling activities were issued based on the proposal of the Council headed by Putin.

According to the registration chamber of St. Petersburg, Prigozhin was the general director of a company that was co-owned by Boris Spector, Prigozhin’s classmate and a member of an organized crime group, and Igor Gorbenko, a director of the “Neva-Chance,” an entity founded by the Foreign Relations Committee headed by Putin.

According to Artyom Kruglov, the editor of the Putinism site, Spector belonged to the organized crime group Kutaisskie which ran the biggest network of casinos in St. Petersburg. Prigozhin was in charge of running a supermarket network and worked for Kutaisskie until 2000–2001.

In 2001, Prigozhin broke up with Kutaisskie and became close to Putin’s personal driver and personal security guards, Roman Tsepov and Victor Zolotov, who eventually became the GRU frontman and a money purse behind the “active measures.”

Kruglov believes that Tsepov and Zolotov introduced Prigozhin to Putin.

Prigozhin's friends. Tsepov: Death by Polonium

Tsepov, aka “Roma Producer,” a former officer responsible for the political education of a unit of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, provided liaisons between casino businesses and the Mayor’s office and ran a private security services company that also specialized in racketeering and robbery. His firm provided protection to St. Petersburg city mayor Anatoly Sobchak and his family, the vice-mayor Putin as well as organized crime bosses.

Tsepov co-produced and played a small part as a bandit in the popular TV series Bandit St.Petersburg. He became an influential person in St. Petersburg and a close Putin ally but, reportedly, fell out of grace for interfering into YUKOS affair.

Tsepov died in 2004, allegedly after drinking tea poisoned by polonium-210, two years before Alexander Litvinenko. Polonium-210 is produced only in Russia, at a factory in Arzamas and the Russian government controls the production. Tsepov’s background and career path were typical: from a communist party ideologue to a criminal to law enforcement and government — and, sometimes, — to a grave, with many murders along the way.

“…In the 1990s it was next to impossible to make serious amounts of money without engaging in practices that were ethically questionable at best, and downright illegal at worst,” writes Marc Galeotti. “During that time, murder was a depressingly common way of resolving business disputes. The notorious “aluminum wars” of the early 90s, for example, saw thugs occupying factories, a string of murders, and lurid accounts of organized crime activity across the metals industries. Recent research suggests that the contract killings related to those wars likely numbered in the thousands.”

“Because of the increase in shootouts among rival gangs over dividing the spoils, Moscow had been compared to Chicago during prohibition,” claimed the 1996 report on Russian Organized Crime at a Hearing in the US Senate.

Zolotov: "Minced meat"

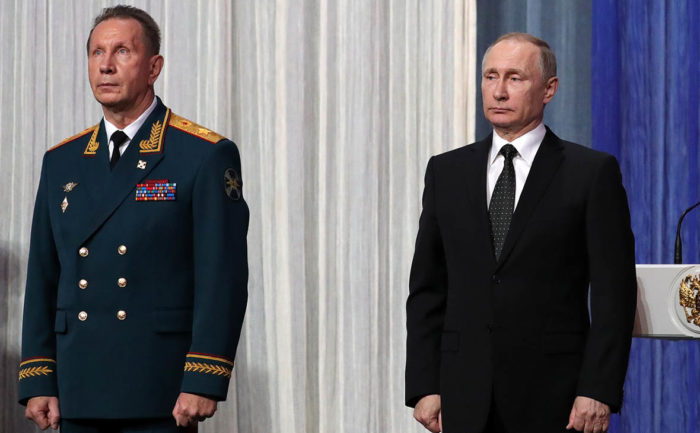

Tsepov’s unofficial partner was Victor Zolotov, at the time the bodyguard of St.Petersburg’s Mayor Anatoly Sobchak and his family and later Putin. Zolotov became Putin’s sparring partner in boxing and judo, and “whenever Putin appeared in public, Zolotov could be spotted walking directly behind him.” In 2018, Zolotov was the Commander-in-Chief of the National Guard of Russia (Rosgvardiya) and a member of the Security Council of Russia.

In October 2018, he made news by promising to make “minced meat” out of the Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny after Navalny’s team conducted an investigation into Zolotov’s multi-million estate.

Prigozhin's food empire grows on state orders

In 2010, Prigozhin’s first food factory complex, the Concord Group, opened outside of St. Petersburg, with Putin in attendance. The state-owned Russian bank Vnesheconombank provided a credit for 30 million euros out of the total project cost of approximately 40 million euros. Putin is on the supervisory board of Vnesheconombank.

In 2008 and 2012, Prigozhin’s company provided catering for inauguration parties for Medvedev and Putin, accordingly. During these years, his companies also won 90% bids of the Ministry of Defense, including food supplies and maintenance.

In May 2017, Alexey Navalny’s Anti-Corruption team found out that Prigozhin ran a cartel breaking the anti-monopoly law. According to the New York Times, state regulators “reviewed eight Defense Ministry contracts won by businesses linked to Mr. Prigozhin and issued a stern rebuke in May 2017… The government announced that it would not press charges… ‘We don’t expect him to be punished given that he is among the president’s closest friends,’ said Maksim L. Reznik, another St. Petersburg legislator demanding that he be investigated.”

In November 2017, the case was closed.

Prigozhin’s catering business also supplies 90% of school lunches in Moscow.

Wars: Information and conventional warfare

No Russian oligarch is the sole owner of his fortune. They pay the Kremlin for the right to operate and make money. Putin and the FSB provide krysha for all Russian oligarchs. The compensation comes in form of monetized kickbacks or services supporting the regime. This is why a small crook and a restauranteur, Prigozhin serves the Kremlin by investing in “troll factories” that spread pro-Kremlin propaganda in Russia and abroad and interfere in the US elections of 2016. Thus, the political and economic mechanisms of a mafia state merge and influence all aspects of life by manipulating public opinion at home and abroad.

In 2012, Prigozhin got involved in a “troll factory” in St. Petersburg. In 2014, he added another propaganda agency “The Federal Agency of News” (FAN.)

“In recent years, the Kremlin has made much use of information warfare, gaining support in the West from nostalgic communist fellow travelers, the rising far-right and conspiracy theorists…The Kremlin has also utilized cultural campaigns, exploiting religious sympathies amongst both fellow Orthodox populations, and religious conservatives in Europe and the USA, who align themselves with Putin’s message of traditional values and homophobia,” wrote hybrid war experts Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss in their critically important and overlooked report in 2014.

In 2016, Prigozhin’s business, Concord Management and Consulting LLC , has interfered in the US elections. It is “one of three entities and thirteen Russian individuals indicted by Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s office in February 2018 in an alleged criminal and espionage conspiracy to tamper in the US race, boost Trump and disparage his Democratic opponent Hillary Clinton," as reported by Reuters.

In 2014, Prigozhin moved from information warfare to traditional combat operations. Journalists traced the connections between his businesses and the Wagner mercenary group in East Ukraine and Syria.

According to article 359 of the Russian Criminal Code, private military companies are illegal in Russia. Recruiting, training, financing, or other material support of a mercenary, just as acting as a mercenary, and the use of mercenaries in armed conflict or military actions are punished with imprisonment. Despite this fact, in 2014–15, Wagner mercenaries appeared in separatist-controlled Donbas in Ukraine and in late 2015, in Syria.

“Wagner has functioned as an undeclared branch of the Russian military: Its fighters fly to Syria on Russian military aircraft, receive treatment in Russian military hospitals, work alongside regular Russian forces in operations, and are awarded Russian military medals signed personally by Vladimir Putin,” wrote the Atlantic. “US intelligence reports suggest that Prigozhin was in touch with both the Kremlin and Syrian officials shortly before and after the attack [in Syria in February 2018] The situation raises big questions about what role a Russian mercenary firm — or rather a “pseudo-mercenary” firm, according to Russian military expert Mark Galeotti — was playing in the Syrian war,” noted the Washington Post,

Wagner: Nazis, pagans, and gas

The private military company Wagner was named after the code name of its leader Dmitry Utkin.

Until 2013, Utkin served as a commander of a Special Forces Detachment of the Russian Military Intelligence. In 2014, Uktin became the head of the Wagner group. His code name was inspired by German composer Richard Wagner, whose music is associated with the Third Reich. According to some reports, Utkin has a swastika tattooed on his shoulder.

Utkin and at least a few mercenaries are also known to be “rodnovery,” practicing a neo-pagan “Slavonic” faith based on a racist ideology that incorporates symbols and rhetorics close to Nazism and Bolshevism. This type of paganism is known to be promoted by the KGB in the 90s.

In November 2017, Putin's Press Secretary Dmitry Peskov confirmed that Wagner’s leader Utkin attended a Kremlin banquet and that Utkin had previously been awarded the Order of Courage for his military service.

Various publications wrote about several other neo-Nazi mercenaries of the Wagner group.

According to a memorandum, signed by the Syrian government (with the participation of the Ministry of Energy of Russia,) 25% of all the gas and oil produced in the oil and gas fields, refineries, and other objects of oil and gas infrastructure in the territory freed from ISIS, reclaimed for Bashar Assad and properly secured against future attacks, reportedly, is transferred to a commercial company OOO “Evro-Polis,” registered in St.Petersburg under individuals associated with Prigozhin’s business.

Fontanka.ru published a detailed investigative report supported by official documents showing the connections. Prigozhin’s empire expanded, adding military and oil and gas industry to the existing catering, maintenance, and construction industrial complexes.

Political murders

Prigozhin uses physical violence and intimidation to silence the press coverage of his operations. Investigative reports into Prigozhin’s business uncovered politically motivated murders, intricate poisoning, and beatings of the opposition in Russia and abroad. In the process of this investigation, the sources disappeared and appeared under murky circumstances.

On 22 October 2018, the Russian outlet Novaya Gazeta, known for its independent investigative research, published an article on Prigozhin and his associates. Journalists spoke to a source who shared details on murder, violence and blackmail carried out on the instructions of Prigozhin’s employees and then went missing under suspicious circumstances — his two phones and one shoe were found in the street — a few hours after meeting with the journalist of Novaya Gazeta on 2 October 2018, only to reappear after several days and ask to close the police investigation into his disappearance.

Valery Amelchenko, a 61 years old former convict, who began working with Prigozhin’s people in 2012–2013, told journalists about various tasks ordered by Prigozhin’s security services, including:

- a murder of an anti-Putin blogger in Pskov who was killed by an injection of an unknown substance in the street;

- beating up of a blogger in Sochi after he had shared a Le Monde’s caricature of Putin;

- a staged car accident in St. Petersburg when a hired homeless person threw himself under the car of an entrepreneur who had a real estate dispute with Prigozhin;

- a hired murder of an important person in Luhansk; and a trip to Syria on February 12, 2017, with the task of testing various poisoning chemicals on the members of ISIS, and other militants captured by the Syrian army.

According to RFE/RL, “unknown persons last week also left a basket containing a severed ram’s head and red carnations” at the office of Novaya Gazeta with a note to the chief editor and the journalist working on the article. The same day, as the article was published, October 22, Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov said that the Kremlin “has seen the article” about Prigozhin but was “not aware of any confirmation of the published information by the competent organs.”

Related: