Eight years ago, using the mechanisms of information warfare, Russia managed to persuade many people that residents of Ukraine's easternmost Donbas region had an actual separatist movement while Moscow simply helped them. Now the Kremlin is trying to apply the same strategy again.

To counter the separatism narrative, Ukrainians are conducting a Twitter campaign under the hashtag #NoSeparatistsInUkraine, launched by Ukrainian political analyst Maria Zolkina. While the Crimean occupation case is better known, the situation on the Ukrainian mainland remains overshadowed. So here are the arguments for why there is no actual separatism in Ukraine.

Despite a lot of economic challenges, Ukraine had no ethnic conflicts in the 1990s

In 1991, Ukraine was lucky enough to avoid internal conflicts such as occurred in the contested Nagorno Karabakh in Azerbaijan. While the inclusion of Karabakh within the confines of the Azerbaijan nation-state was unacceptable to many Armenians, Ukraine had no strict ethnic divisions.

Instead, 91% of the Ukrainian population voted for independence in 1991, including more than 80% of people in every southern and eastern region.

Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in the 1990s were among the centers of protest activity, albeit generally of an economic nature. The collapse of the USSR caused a severe economic crisis, leaving Ukrainian miners without salaries and social support. In 1993, they launched a general strike in Donbas, with these protests being subsequently repeated almost annually.

Political demands appeared only once, in 1993, when protesters demanded economic autonomy for the two Donbas oblasts. Their local councils had even conducted a survey on this topic. However, according to historian Dmytro Snegiriev, in this case, local authorities were exploiting the people for their own material benefit.

This was indirectly proven after 1993 when protesters merely voiced economic demands. In 1998, Donbas miners staged a march on Kyiv, seeking the attention of the government. Later their protests in Luhansk were brutally dispersed by the regional Berkut police unit, reportedly backed by local political elites.

Miners from the Donbas region marching on Kyiv, 1998.

The main reason for the absence of real separatism in the East of Ukraine is apparent: in contrast to Catalans or Kurds, there are no separate Donetsk or Luhansk nations or languages.

People from these oblasts are widely regarded as ordinary Ukrainians, and become successfully integrated into local communities in Kyiv and other cities.

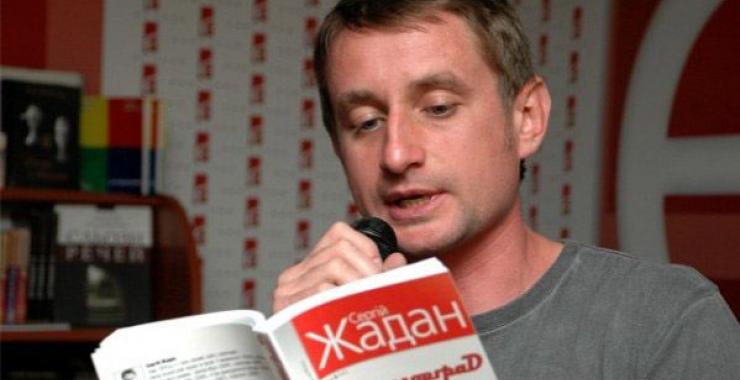

Writers Serhiy Zhadan from Luhansk and Iren Rozdobudko from Donetsk; Ivan Dziuba, a linguist and dissident from the south of Donetsk Oblast; and Serhiy Rebrov, football player and coach born in a Donetsk suburb (later he would become the legend of the football club Dynamo Kyiv) are among the brightest examples of famous Ukrainians from the two eastern oblasts.

It would be an exaggeration to fully deny the existence of secessionists in Donbas. While several local separatist organizations operated there in the 2010s, they had no actual influence. The Donetsk Republic movement was founded in 2005 and even declared independence for Donbas. However, before 2014 their rallies would only attract about 40-50 people.

Local elections in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in 2006 and 2010 were the best proof. No secessionist parties were elected to local councils, although some deputies had pro-Russian views. The result was similar in the southern oblasts of Kherson, Mykolayiv, Zaporizhzhia, and Odesa.

This situation is in stark contrast to Catalonia, where the parliamentary majority is formed by openly irredentist parties and citizens stage mass pro-independence rallies.

The case of “Ukrainian separatism” was artificially created in 2004 for political purposes

The relatively peaceful Ukrainian situation was intentionally undermined during the 2004 presidential race. Political elites were desperate to secure the victory for their nominee Viktor Yanukovych (a native of Donbas). Unable to solve Ukrainian economic problems, the Party of Regions resorted to divide and rule tactics.

Seeking to mobilize voters in the South and East, Yanukovych`s staff made use of a narrative, according to which Russian-speaking industrial regions were suffering from discrimination in Ukraine and needed to fight for the candidate who would protect them from western compatriots.

The most notorious examples of this propaganda were posters with claims that Viktor Yushchenko (a candidate more popular in the western region) saw the inhabitants of the east as third-class citizens (it was done to scare the voters).

Another example of agitation was spreading fake leaflets with Yushchenko's name promising a "national dictatorship", eradication of the Russian language, and repression of national minorities.

At the same time, Yanukovych's team staged a brutal electoral fraud, with protests against it leading to the Orange Revolution. The Party of Regions responded by convening a congress in Sievierodonetsk

, which threatened to create an autonomous republic and called referendums in Luhansk and Donetsk.

These tensions are often cited as a turning point and proof of "two Ukraines": a pro-European West and pro-Russian East.

But in reality, it was more a political struggle involving two parties than a real civil conflict. Later in 2005, elected president Yushchenko and Yanukovych signed a joint memorandum (without mentioning any autonomy). The Party of Regions voted for Yushchenko's nominee for the prime minister post, while investigations concerning Sievierodonetsk never resulted in custodial sentences. The following year Yushchenko nominated Yanukovych and the latter became head of the government.

To compare, it would be hard to imagine Carles Puigdemont, leader of Catalan independence supporters, abandoning his case in exchange for a post in the government of the united Spanish state.

The best argument for the absence of actual separatism in Ukraine was public opinion. With the end of the Euromaidan in March 2014, the International Republican Institute conducted a poll which showed that only 2% of people in the South and 4% in the East supported the division of Ukraine and the creation of new states.

The overwhelming majority supported the country’s unitary status. It is noteworthy that some people were ready to accept the loss of Crimea, but did not want their region to follow suit.

But in 2014 Kremlin used it as a pretext for seizing Ukrainian territories

The absence of strong separatist movements did not prevent Russia from taking advantage of this occasion after the Revolution of Dignity, using hybrid tactics with mass propaganda and involving local pro-Kremlin movements.

However, in the southern oblasts (Kherson, Odesa, Mykolayiv, and Zaporizhzhia) pro-Russian demonstrations failed. In each of them, pro-Ukrainian rallies were more numerous, demonstrating support for the unity of Ukraine.

For example, in Zaporizhzhia, previously seen as a pro-Russian city by Kremlin planners, activists pelted separatist supporters with flour and eggs, disrupting their protests. In Odesa, it resulted in street clashes, with the situation subsequently stabilizing.

Pro-European and pro-Ukrainian candidate Petro Poroshenko then won the next presidential election in all these oblasts.

The situation in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts was more complicated, but not because of broad support for separatism.

Actually, Donetsk residents organized large-scale pro-Ukrainian rallies, the biggest bringing 10,000 people out onto the streets. Pro-Russian residents also held meetings, but none of them reached that figure. Then the non-locals appeared.

"Apart from the 200 communists dreaming about the USSR, criminals, and marginals from depressed areas brought by Sasha the Dentist [nickname of former President Yanukovych`s son], appeared, joined by “guests” from Belgorod and Rostov,” said journalist Tetyana Zarovna, former Donetsk resident.

Indeed, the media cited local citizens claiming unknown people with a Russian accent in Donetsk.

As an example of outsiders’ role, one of the rallies featured “miners” wearing construction helmets instead of miners' ones – the difference would be obviously apparent in a mining region.

Finally, pro-Russian forces succeeded by applying terror, just like the Taliban or Islamic State. On April 13, they attacked a peaceful pro-Ukrainian rally in Donetsk, beating people with batons and killing one activist. Then a series of kidnappings and murders started (including the murders of local councilor Volodymyr Rybak, student Yuriy Popravka, Pentecostals

in Sloviansk). The large pro-Ukrainian majority could not express its position and often had to leave.

All of this helped militants seize Donetsk (as well as Luhansk) proclaiming the so-called “DNR-LNR”.

Russia created and supported so-called “DNR-LNR” while denying this fact

The Ukrainian state could not quickly restore order in Donetsk, remaining concentrated on the important city of Sloviansk. In April 2014, Sloviansk was captured by Igor Girkin, a Russian citizen, and a group of militants. As Girkin himself admitted, no "DNR-LNR" would emerge without it.

"After all, I pulled the trigger of the war. If our detachment had not crossed the border everything would have ended as in Kharkiv and Odesa," he said in an interview.

It is the reason why Ukrainians don't consider the so-called "DNR-LNR" as separatists but as Russian proxy forces. Only with the use of Russian support (including military one) did they manage to seize part of the two oblasts and establish their own governing bodies there.

The same stance was taken by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, which adopted Resolution № 2133 in 2016, calling "DNR-LNR": "created, supported and effectively controlled [which means indirect leadership without formal recognition of occupation] by the Russian Federation". The Venice Commission later also cited this conclusion. There is a large quantity of direct evidence:

- "DNR-LNR" are financed by Russia. It spends 1.3 billion dollars per year on salaries alone. According to Radio Liberty, before the invasion, the Kremlin was going to allocate another 900 billion rubles for the needs of these territories.

- The Russians indirectly control these territories. According to Radio Liberty, Dmitry Kozak, deputy head of the Russian presidential administration, serves as the main curator of “DNR-LNR”. The deputy head of the so-called "government" in Donetsk is Vladimir Pashkov, who until 2014 had held a similar position in Irkutsk Oblast. Pashkov regularly reports to Moscow.

- The military forces in "DNR" and "LNR" are ruled by Russian officers. The InformNapalm investigation team was able to identify Major Generals Sergei Kuzovliov and Yevgeny Nikiforov acting in the region. According to the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense, in 2021 600-800 Russian officers were permanently stationed there to lead the local militants. They are armed with a whole arsenal of Russian-made equipment.

This explains why the so-called "Donbas separatism" ends immediately behind the frontline. For eight years, no serious separatist parties or movements arose in the Ukraine-controlled territories of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts (not to mention the South). On the contrary, the residents of Rubizhne, occupied in 2022, staged a protest under the yellow-blue flag after being deported to occupied Luhansk.

Yuriy Prymachuk is a freelance journalist and editor from Ukraine. He received a master’s degree in Institute of Journalism, Kyiv, interned in Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, worked as a journalist and editor in political and economic fields.

Read more:

- Ukrainians of occupied towns protest against Russian invaders, undermining “liberator” narrative

- Russia sends Donbas musicians and historians as “cannon fodder” in Ukraine war

- Stalin-era city names to be used in occupied Donetsk, Luhansk as part of “great victory” cult (2020)

- Russia prepared to occupy Crimea back in 2010 and other things we learned from Yanukovych’s treason trial

- Ukraine publishes video proving Kremlin directed separatism in eastern Ukraine and Crimea

- The rise and decline of Donbas

- Russian citizens driving separatism activity, says Donetsk governor (2014)

- Pro-Ukraine demonstrations held in Luhansk, Odesa, and Kryvyy Rih (2014)