Condemnations throughout the international community increasingly characterize Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin as a war criminal responsible for horrific atrocities being reported since the Russian invasion in February and continuing aggressive occupation of Ukraine. From unconfirmed reports of alleged chemical attacks on Mariupol to accusations of Russian forces targeting civilians in the Kramatorsk missile attack, to reported sexual violence against women and children and human trafficking, to reports of mass graves amidst devastation and loss in Bucha, to reports of alleged murders, rapes, torture by Russian forces—the brutality amounts to international crimes for which Russia’s head of state and high-ranking officials must be held to account, a growing chorus of experts urge.

- On 16 March, the International Court of Justice ordered Russia to suspend military operations in Ukraine, but Russian hostilities persist.

- As of 12 April, the Ukrainian Prosecutor General’s office had registered 6,036 investigations into crimes of aggression and war crimes with 501 suspects; by 13 April, there were 6,261 investigations.

- The UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner recorded 7,061 civilian casualties in the country (3,381 killed and 3,680 injured) between the start of the Russian invasion on 24 February and 9 May, noting that most were caused “by the use of explosive weapons with a wide impact area, including shelling from heavy artillery and multiple launch rocket systems, and missile and air strikes” and that it believes the figure is much higher. Ukrainian authorities estimate that at least 20,000 civilians have been killed in the besieged city of Mariupol alone and note that the exact number will be impossible to determine due to Russia hiding up its evidence of war crimes.

History’s foothold on prosecuting war criminals

The Hague Conventions adopted in 1899 and 1907 codified international humanitarian law, also known as the law of armed conflict, prohibiting certain behaviors between warring parties. Thus began the articulation of war crimes under international humanitarian, criminal and customary laws over the years and warring conflicts that followed.

The codification of international crimes—including who can be held accountable and in what context—has continued to evolve.

In 1918, the former German emperor William II had fled to The Netherlands. With the signing of the 1919 Versailles Treaty, the German government accepted that this high-ranking official be tried in a special tribunal for “a supreme offence against international morality and the sanctity of treaties” (Article 227), but a year later the Dutch government refused the Allied Powers’ request to extradite him. The German government had also accepted “the right of the Allied and Associated Powers to bring before military tribunals persons accused of having committed acts in violation of the laws and customs of war” (Article 228), but few trials actually took place.

At the very least, the treaty had broken new ground in international law in its attempt to identify individual, not only state, responsibilities.

War crimes and crimes against humanity

A quarter of a century later and another world war, rules and precedent for the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal (IMT) and, similarly, for the Far East (Tokyo) IMT, established that:

“Crimes against international law are committed by men, not by abstract entities, and only by punishing individuals who commit such crimes can the provisions of international law be enforced.”

International Military Tribunal (Nuremberg), Judgement of October 1, 1946

The charters of both the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals defined “war crimes” as violations of the laws and customs of war and “crimes against humanity”—a novel concept developed by Hersch Lauterpacht, an international lawyer in the trials who, by the way, had studied at Lviv University—as crimes against international law.

The statutes of the tribunals prescribed, among others, such crimes as “crime against peace” to include planning, preparing, or waging a war of aggression, that is, a war in violation of international treaties, agreements, and assurances.

In the first Nuremberg trial, 24 Nazi government leaders—diplomats, economists, politicians, and military officials—were charged with international crimes including war crimes and crimes against humanity. Of those, 19 were convicted and 12 sentenced to death.

War crimes themselves encompass a wide range of illicit actions committed in the course of armed conflict in violation of the Geneva Conventions. They include:

- the willful killing of civilians;

- torture and inhuman treatment;

- unlawful deportation;

- destruction of civilian property and many other crimes (Article 8 of the Rome Statute).

Whereas, crimes against humanity include systematic, intended attacks against civilian populations by means of murder, rape, extermination, torture, imprisonment, etc. (Article 7 of the Rome Statute) that occur during times of peace as well as war.

Genocide

The term “genocide” (derived from genos, “race, people,” and caedo, “act of killing”) was coined in 1944 by Raphael Lemkin, a prominent international lawyer and scholar who had studied at Lviv University. Notably, he was the first international law expert to classify the crimes of the Soviet authorities in 1926 and 1946 against Ukrainians as genocide.

Genocide is generally considered “the crime of all crimes,” as no crime causes more deaths in a shorter period of time. The prohibition of genocide is a jus cogens norm, meaning no exceptions are permitted and the prevention of genocide is a responsibility of every state (erga omnes partes obligation).

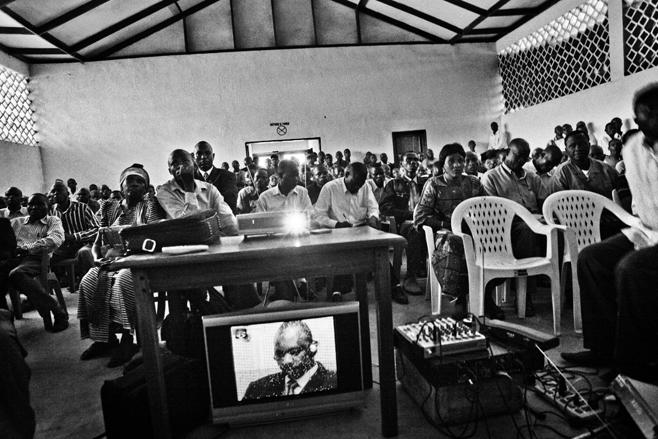

Nearly half a century later, UN Security Council resolutions mandated ad hoc international criminal tribunals, one in 1993 for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and one in 1994 for Rwanda (ICTR), to prosecute individuals responsible for “widespread and flagrant violations of international humanitarian law” committed respectively during the Yugoslav warring conflicts since 1991 and the Rwanda genocidal events in 1994.

From 1993 to 2017, ICTY indicted 161 individuals, including heads of state, prime ministers, army chiefs-of-staff, interior ministers as well as other high- and mid-level political, military, and police officials.

In the trial of former president of Yugoslavia Slobodan Milošević on 66 international criminal charges, prosecutor Carla Del Ponte in her opening remarks stated:

“This Tribunal, and this trial in particular, give the most powerful demonstration that no one is above the law or beyond the reach of international justice.”

The trial ended when Milošević died, in March 2006, before a verdict was reached.

Radovan Karadžić, president of the self-declared Republika Srpska (Bosnian Serb Republic), and Ratko Mladić, Commander of the Main Staff of the Army of Republika Srpska, were found guilty of genocide, crimes against humanity, and violations of the laws or customs of war. Both were ultimately sentenced to life imprisonment for:

- genocide in Srebrenica in 1995;

- persecution, extermination, murder, deportation, inhumane acts of forcible transfer in several municipalities in Bosnia and Herzegovina;

- murder, terror, and unlawful attacks on civilians in Sarajevo; and

- hostage-taking of UN personnel.

The statutes of the ICTY and ICTR similarly defined their jurisdiction over individual criminal responsibility, calling on the international community for cooperation and assistance in the investigation and prosecution of such individuals (Article 28).

The ICTR was the first international tribunal to prosecute individuals for the crime of genocide and of rape as a means of committing genocide, and to prosecute “members of the media responsible for broadcasts intended to inflame the public to commit acts of genocide.”

Among the 93 individuals indicted:

- Former Rwandan Prime Minister Jean Kambanda was found guilty of crimes against humanity and genocide, receiving a sentence of life imprisonment affirmed on appeal in 2000;

- Athanase Seromba, a parish priest, was indicted and convicted of aiding and abetting genocide and crimes against humanity; his conviction and sentence of life imprisonment were affirmed on appeal in 2008;

- Mikaeli Muhimana, a sector conseiller, was indicted and convicted for genocide, rape, and murder; his conviction and sentence of life imprisonment were affirmed on appeal in 2007;

- In the tribunal’s so-called “media” case against Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza, Ferdinand Nahimana and Hassan Ngeze, mainly in relation to a radio station and newspaper, convictions for genocide, conspiracy to commit genocide, direct and public incitement to commit genocide, and extermination as a crime against humanity were upheld and life imprisonment sentences were reduced on appeal in 2007.

In 2004 the Special Court for Sierra Leone ruled that the position of Head of State does not prevent him “from being prosecuted before an international criminal tribunal or court.”

Ad hoc tribunals for the prosecution of international crimes were created under the auspices of the United Nations.

The Special Court for Sierra Leone (2002), Special Tribunal for Lebanon (2007), and Special Tribunal for Cambodia (2003) were established on the basis of an agreement between the United Nations and those states.

The ICC is defined as a permanent institution with “the power to exercise its jurisdiction over persons for the most serious crimes of international concern,” in particular: genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crime of aggression (Articles 1 and 5 of the Statute).

Individual criminal responsibility for genocide is provided for in the Rome Statute, while the obligations of states are provided for in the Genocide Convention. Under both,

Intent is decided by the court on a case-by-case basis, “inferred from relevant facts and circumstances.”

While the crime of aggression has its roots in the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals, when negotiating the ICC Statute during the 1998 Rome Conference, states decided to include the crime of aggression in the Statute but could not reach a consensus as to its wording. In 2010, states parties to the Rome Statute finally agreed on the Kampala Amendments, which carefully articulated the crime of aggression under ICC jurisdiction in Article 8bis. ICC jurisdiction over this crime was “activated” in 2017, with state parties agreeing on its exercise starting 17 July 2018.

Article 8bis of the Rome Statute defines the crime of aggression as follows:

“‘crime of aggression’ means the planning, preparation, initiation or execution, by a person in a position effectively to exercise control over or to direct the political or military action of a State, of an act of aggression which, by its character, gravity and scale, constitutes a manifest violation of the Charter of the United Nations.”

Article 8bis specifically addresses the responsibility of heads of state and high-ranking officials (including ministers of defense and high-level military generals). As it was proclaimed in the 1947 High Command case (US v. Wilhelm von Leeb, et al.), one of 12 cases heard by US courts against Nazi commanders, even in an autocratic state a single person acting alone cannot have formulated an aggressive war policy and implemented it.

Of the 31 cases before the ICC, 5 reached a guilty verdict, 6 are being tried, and 1 is undergoing appeal. The ICC has convicted three former leaders of Congolese rebels who committed war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Ituri region in the north-east of the Democratic Republic of Congo: Thomas Lubanga Dylio, president of the Union des Patriotes Congolais and its military wing Forces Patriotiques pour la Libération du Congo (FPLC); Bosco Ntaganda, Deputy Chief of Staff of FPLC, and Germain Katanga, leader of Force de résistance patriotique en Ituri, an armed group in Ituri.

Eleven ICC cases are pending at the pre-trial stage because the suspects have not been brought before the Court. The ICC cannot try individuals in absentia; article 63(1) of the Rome Statute clearly provides “[t]he accused shall be present during the trial.”

Even with an international warrant by the ICC, the decision to hand over a suspect rests solely on the state. One such case is against former president of Sudan Omar Hassan Ahmad Al Bashir for crimes against humanity and genocide, for whom an arrest warrant was issued in 2009. Sudan has yet to deliver the ex-president, despite the Memorandum of Understanding signed in 2021 between the Sudanese government and the ICC.

On Ukrainian soil

After seeing what happened in Bucha, many people tried to find the right word to describe that unimaginable brutality. The word “genocide” unsurprisingly appeared in the media. But can we name what happened in Bucha and other Ukrainian cities a genocide, not only in metaphorical, but also in legal sense? Were the Russian troops guided by an intent to destroy Ukrainians as a nation? To answer these questions, the following facts should be recalled.

On 21 February Russian President Putin declared that “Ukraine never had a tradition of genuine statehood.” In the early morning of 24 February, he justified the invasion of Ukraine as a “denazification” plan. The Russian state-owned media RIA News provides the following explanation:

"Denazification will inevitably result in de-Ukrainization, the abandoning of the full-scale artificial development, introduced by the Soviet government, of the ethnic component of the population’s self-identification based on the historically formed territories of ‘Malorossiya’ (little Russia) and ‘Novorossiya’ (new Russia). [...] Ukraine, as history has shown, is impossible as a nation-state."

Therefore, Putin directly in his speech and indirectly through Russia’s media doubts and even denies the existence of Ukrainians as a nation.

Horrifying reports allege that atrocities including murders, rapes, and torture were committed by Russian troops in Ukraine, including in the recently liberated town of Bucha, near Kyiv. In his speech before the UN Security Council, Volodymyr Zelenskyy said “[i]t is difficult to find a war crime that the occupiers would not have committed there.”

On 1 April 2022, after Russian forces withdrew from the Ukrainian town Bucha, 410 dead bodies and mass graves were found. In addition, thousands of children were forcibly transferred from occupied regions to Russia.

After a maternity hospital was bombed in Mariupol, a wounded woman died along with her baby born with no sign of life.

The position of the President of Ukraine V. Zelenskyy was straight: “Indeed, this is genocide, the elimination of the whole nation and the people.” And Ukrainian lawyers and law associations issued a joint call urging states parties to the Genocide Convention to step in and stop the murders of Ukrainians.

Related:

- Bucha: a turning point–not only in Putin’s war in Ukraine, but in relations between Moscow and the world

- Cruelty, murder, and destruction in Bucha

- Bucha massacre: Ukraine urges ICC to gather evidence of Russian war crimes

- Russia turned Bucha into one big torture chamber. Dispatch from Ukraine

- “They were shot in the back of the head.” Eyewitness account of Russia’s murders of Bucha residents

Can Putin be punished for genocide?

One may ask whether Putin and Russia as a whole may be punished for committing genocide. International law provides two forms of responsibility for genocide committed in Ukraine.

Firstly, Russia as a state can be held responsible by the ICJ, which having a mandatory jurisdiction under the Genocide Convention, to which Ukraine and Russia are parties.

On 26 February, Ukraine filed a claim to the ICJ alleging Russia’s violation of the Genocide Convention. On 16 March, the ICJ ordered Russia to suspend military operations in Ukraine and recognized that no evidence was provided to substantiate Russia’s allegation of genocide committed by Ukraine as justification for such operation. Decisions on jurisdiction of the Court and substance of Ukrainian claims are yet to be rendered.

Secondly, Putin can be held responsible, as an individual, who at least “directly and publicly incites others to commit genocide.” In this context, Article IV of the Genocide Convention reads as follows:

"Persons committing genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in article III shall be punished, whether they are constitutionally responsible rulers, public officials or private individuals."

Concerning the ICC, neither Ukraine nor Russia is a state party to the Rome Statute. Nevertheless, Nevertheless, acceptance by Ukraine of the ICC’s jurisdiction in 2014 and 2015, as well as referrals of 41 states parties enabled ICC Prosecutor Karim A.A. Khan QC to open investigations into alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Ukraine.

It may be difficult, however, to meet the required threshold of proof connecting the Russian head of state with the alleged crimes committed by Russian soldiers on Ukrainian soil. International lawyer Philippe Sands QC, outlines the difficulty:

"The difficulty with crimes against humanity and war crimes is that you have to show a direct connection between the act that amounts to the crime, and the perpetrator. …. By focusing on crimes against humanity and war crimes, you’re going to end up in seven years’ time with trials of mid-level folk. And the big issue, the waging of an illegal war, is never going to go to justice. That’s why I wrote that war crimes and crimes against humanity investigations alone could end up as a means of letting the main man off the hook."

Can Putin be punished for crime of aggression?

One may ask – can Putin and other high-ranking officials be tried for the crime of aggression against Ukraine before the ICC? Can the ICC Prosecutor commence investigation in respect to this crime as well?

Unfortunately, unlike other crimes under the Rome Statute, the threshold for exercising jurisdiction over the crime of aggression is quite high. According to the Statute, the ICC may exercise jurisdiction in relation to this crime only if:

- the state on whose territory the crime was committed and the state whose nationals committed the crime are parties to the Rome Statute (Article 15bis(5));

- or by referral from the UN Security Council to the ICC for consideration (Article 15ter).

Given that Russia is a permanent member of the Security Council with veto power, a referral by the UN Security Council is unlikely to happen. At the same time, Russia is not a party to the Rome Statute. Even if Ukraine accepts the ICC jurisdiction with respect to the crime of aggression, Russia would not do so for obvious reasons.

Even though it does not seem possible to hold Putin and his allies accountable for the crime of aggression before the ICC, there is a possibility to create an ad hoc tribunal for that purpose. A call for creating this special tribunal started as an initiative of scholars, and was supported by Ukrainian officials.

Ukraine is currently gathering a coalition of states to gain political support. Establishing such a tribunal would require either a resolution of the UN Security Council, as it was with the the ICTY and the ICTR, or an agreement between the United Nations and the governments of those states, as it was with the Special Court of Sierra Leone, Special Tribunal for Lebanon, and Special Tribunal for Cambodia.

In this case, neither option is likely to happen in the nearest future, given the lack of political will of the current Russian government and Russia's veto powers in the Security Council.

However, it is still possible to bypass Russia’s veto powers via the UN General Assembly. If the Security Council fails to exercise its powers, the General Assembly may take the lead and adopt the decisions that the Security Council failed to adopt.

For instance, in 1950, during the outbreak of the Korean War, the General Assembly adopted Resolution 377 (Uniting for Peace), which introduced such a mechanism as an emergency special session to deal with the issues that the deadlocked Security Council was unable to resolve. Further, this mechanism was used to introduce economic sanctions and establish peace-making missions. Although resolutions of the General Assembly are only recommendations, they may serve as a valid justification for states to introduce the recommended measures.

The UN General Assembly commenced an emergency special session on 28 February and adopted a resolution condemning Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. While the emergency session is ongoing (albeit adjourned), it is possible to press for the creation of an ad hoc tribunal on the crime of aggression if such political will is expressed by a majority of UN member states.

According to an analysis by Alexander Komarov and Oona Hathaway:

“...creating the court through concluding a treaty between Ukraine and the United Nations ensures that the court will be consistent with Ukrainian law and provides a path to insulating it from future constitutional challenge. The Law of Ukraine on International Treaties of Ukraine provides that a treaty between Ukraine and the UN might be made subject to ratification by the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine.…To avoid any constitutional concerns that may arise during ex ante review, the agreement between Ukraine and the UN should specify that the new court will be international, not domestic or hybrid (avoiding conflict with Art. 125). It should also specify that the court is auxiliary, not complementary, to the domestic courts (avoiding conflict with Art. 124).”

Can Putin et al. hide from criminal responsibility behind the immunity shield?

Even if we assume that the evidence of committing the aforementioned international crimes is sufficient, is it possible to prosecute Putin and other Russian officials?

Prosecution of high-ranking state officials, such as Heads of States is no easy task. A serious obstacle precluding their accountability for international crimes is immunity from criminal responsibility. Such immunity poses considerable risks for the possibility to enforce any warrant, order, not mentioning a verdict against a person enjoying the immunity.

Heads of state and state officials are accorded two types of immunity under customary international law:

- Functional immunity (ratione materiae) applies to all state officials even after their term of office has expired and covers only acts performed by them in an official capacity.

- Status immunity (ratione personae) applies to a limited number of state officials (Head of State, Head of Government, and Minister for Foreign Affairs) during their term of office and covers all their acts performed in a private or official capacity.

At first sight, it may seem that Putin, as Russia’s President, enjoys both mentioned immunities. Such a view was even expressed by Iryna Venediktova, Ukraine’s Prosecutor General, who said that:

“He has functional immunity. […] Pursuant to the norms of international and national law, we cannot initiate specific proceedings while he is the President of the Russian Federation.”

Nevertheless, the issue is not so straightforward - immunity is not absolute.

Exceptions to functional immunity

In 2017, the International Law Commission (ILC), responsible for the development and codification of international law, recognized exceptions under which functional immunity does not apply: they include genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and torture.

The ILC did not include an immunity exception for the crime of aggression due to the lack of state practice at either the legislative or judicial level. Given rapid developments in international law and existing debates around this issue, the applicability of a functional immunity exception to the crime of aggression can be reasonably anticipated.

Therefore, a state official shall not hide behind the so-called functional immunity shield to avoid prosecution for international crimes committed in an official capacity. So, Putin’s chances to escape prosecution for committing international crimes in Ukraine since 2014 by invoking functional immunity are not as high as it may seem.

Status immunity: to be limited or not?

Although functional immunity shall not be applied to Putin, he still enjoys status immunity before foreign domestic courts as long as he holds the position of Russia’s president. In contrast to functional immunity, status immunity applies even in the case of the most serious international crimes, as the ICJ expressly recognized. This means that no rules of customary (uncodified) international law provide limitations for status immunity before foreign domestic courts beyond the limitation of time or term of office.

Is the situation hopeless? The answer is no, as the limitations to status immunity do not extend to proceedings before international courts.

In 2004 the Special Court for Sierra Leone ruled that the official position of Head of State does not prevent him “from being prosecuted before an international criminal tribunal or court.”

The same approach was supported by the ICC in the Al Bashir case when the Court rejected the invocation of heads-of-states immunity. Article 27 (2) of the Rome Statute reads as follows:

“Immunities or special procedural rules which may attach to the official capacity of a person, whether under national or international law, shall not bar the Court from exercising its jurisdiction over such a person.”

The ICC concluded that Article 27 (2) constitutes not only a provision of conventional law but also “reflects the status of customary international law”. The thinking reflects the fact that, contrary to domestic courts, international courts “adjudicating international crimes, do not act on behalf of a particular State or States. Rather, international courts act on behalf of the international community as a whole.”

Given that reasoning, Putin, as a head of state, shall not enjoy status immunity before the ICC, despite the fact he is a national of a non-party state to the Rome Statute, as well as before a special tribunal adjudicating international crimes committed against Ukraine (when one is established). However, he still cannot be prosecuted before foreign domestic courts.

Next steps for bringing Putin accountable for war crimes in Ukraine

As we see from the above, there exists a possibility to hold Putin, Russian high-ranking officials, soldiers, and their supervisors accountable for international crimes. But let’s be honest – bringing perpetrators to justice will take years. While Russian aggression continues and reports on horrible atrocities appear, one may doubt whether it is worth the time and effort.

Justice will not come today or tomorrow, but in the words of the ex-chief prosecutor of the ICTY and ICTR, Ms Carla Del Ponte, when she called for an international arrest warrant for Russian President Putin:

"You mustn’t let go, continue to investigate. When the investigation into Slobodan Milosevic began, he was still president of Serbia. Who would have thought then that he would one day be judged? Nobody."

As Associate Editor Susan D’Agostino for the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists reports:

“Russia broke international humanitarian law and committed war crimes in Ukraine by targeting civilians, a maternity hospital, and a theatre, according to an Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe report released this week. The Vienna-based organization also found ‘clear patterns’ of additional international humanitarian law violations and war crimes. They have called for more detailed investigations.”

Indeed, evidence of atrocities is being gathered through a growing number of investigations at both the global and international levels and within Ukraine, on alleged violations of international humanitarian and human rights laws as well as possible war crimes and crimes against humanity. ICC Prosecutor Karim A.A. Khan and his team arrived in Ukraine to collect evidence of war crimes committed by Russian troops.

“The amount of documentation being assembled is beyond precedent,” according to international human rights lawyer Flynn Coleman in his analysis for Foreign Policy.

Collecting, preserving, documenting, verifying, and archiving credible evidence are the first critical steps, if the alleged international crimes are to be prosecuted and the perpetrators ultimately held to account.

The Ukrainian government has set up various digital nodes to collect witness accounts and information about atrocities and damages:

- https://dokaz.gov.ua/

- https://diia.gov.ua/

- https://www.warcrimes.gov.ua/

- https://damaged.in.ua/

- https://t.me/war_crime_bot

- https://damaged.in.ua/

- https://t.me/stop_russian_war_bot

These are indeed arduous, painstaking steps in what promises to be years - if not decades-long processes at multiple levels of seeking justice for the country and people of Ukraine. Publicly accessible repositories, such as the online archive collected by the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, have only begun to share with the world the mounting evidence of atrocities being committed.

Hanna Yareha is a legal counsel at SoftServe and a moot court participant with a solid background in public international law

Kateryna Ilieva works in the dispute resolution practice of AEQUO law firm and participated in moot courts, such as Jessup and FDI Moot.

Nataliia Savula is an international arbitration associate at Asters Law Firm with strong public international law and international investment law background.

Nataliia Savula is an international arbitration associate at Asters Law Firm with strong public international law and international investment law background.

Read more:

- Making Russia answer for destroying cultural heritage in Ukraine

- How Russia could be removed from the UN Security Council

- ICJ examines Ukraine’s case regarding Russia’s false pretext of “genocide” to invade Ukraine

- Ukraine vs Russia at the ICJ: It is not Ukraine commiting genocide, but Russia committing war crimes in Ukraine

- Bucha: a turning point–not only in Putin’s war in Ukraine, but in relations between Moscow and the world

- Cruelty, murder, and destruction in Bucha

- Bucha massacre: Ukraine urges ICC to gather evidence of Russian war crimes

- Russia turned Bucha into one big torture chamber. Dispatch from Ukraine

- “They were shot in the back of the head.” Eyewitness account of Russia’s murders of Bucha residents

- How Russia justifies the murder of Ukrainians: Russia’s 2022 “genocide handbook” deconstructed

- Russia’s call for genocide of Ukrainians outstrips Mein Kampf

- Ukraine’s international law victories over Russia ring hollow as West rejects practical measures of support