The Resolution formally enshrined Stalin’s directives, voiced by the Soviet leader on January 21, 1930 in his appeal ‘On the policy of liquidation of the kulaks as a class’.

“In order to eliminate the kulaks as a class, it is necessary to openly break their spirit and resistance, and deprive them of the sources for further existence and development. The party’s current policy in the towns and villages marks a new procedure for eliminating the kulaks as a class,” said Joseph Stalin, secretary general of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR.

Stalin’s first objective was to rid society of the peasantry, which concealed ‘capitalist elements (kulaks)’, and was thus irrevocably hostile to the regime. Dekulakization consisted in expropriation, eviction of entire families, deportation of millions of farmers, and, in the event of resistance, physical annihilation.

This Resolution defined dekulakization quotas, i.e. first and second categories for each region or republic of the Soviet Union. The first category kulaks, defined as ‘activists, engaged in counter-revolutionary activities’, were to be arrested and sent to labour camps after a brief appearance before the so-called judicial ‘troika’. The most ‘dangerous’ activists were to be sentenced to death while second-category kulaks, defined as ‘exploiters, but less actively engaged in counter-revolutionary activities’, were to be deported to distant Siberian regions. Dispossessed, deprived of their civic rights, deported, exiled to remote areas of the USSR, these kulak families were assigned to ‘special villages’ run by the OGPU (NKVD as of 1934).

In January 2020 (90th commemoration of the total extermination of private property in the USSR), Radio Liberty and the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide launched a special project – ‘Dekulakization: how the Stalinist regime destroyed Ukraine’s free peasant class’. Hundreds of testimonies about dispossessed and persecuted families have been sent to Radio Liberty’s editorial office and been reprinted online.

Short narratives published on Radio Liberty’s FB page

Elena Lanher

My great-grandfather was dekulakized (dispossessed) because he’d installed a wooden floor in the house. He never reached Solovki prison camp, but died on the way.

My great-grandmother with two children (grandfather was 4 years old and his brother had just been born) wandered around the countryside, staying in other people’s homes. There was nothing to eat; the older child looked after his baby brother while great-grandmother went to work.

Olha Varchyk

Our family was sent to Siberia. After being rehabilitated, we returned to our hometown. However, a residence permit was required, and the town clerk said that we were “enemies of the people and there was no place for us in the town”.

Some relatives helped us out. They talked to the local “comrade” on behalf of our family. He took a sheet of paper and wrote down a certain sum of money. My mother was outraged. The “comrade” ordered us to leave town, so we headed to the Donbas.

Iryna Prykhodchenko

My great-grandfather was a wealthy peasant in Odesa Oblast. He and his family were dispossessed of everything. He then sat down on a bench and refused to get up; his heart finally gave out.

There were two children. The youngest was two months old. Due to malnutrition, my great-grandmother couldn’t produce enough milk to breastfeed her child. All grain and food had been confiscated. The baby died. She then took her eldest daughter (my grandmother) and they settled in Chernihiv Oblast.

For the rest of her life, my great-grandmother hated the Soviet government. She couldn’t forgive them for the loss of her loved ones. She never worked for the Soviet government; she made a modest living selling home-grown vegetables. She was periodically imprisoned for black marketeering.

It was our neighbours who denounced our family; they reported that my great-grandfather stored grain in the barn.

Tetiana Krupoder

My family lived through this horror.

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. My great-grandfather was a good farmer, so he was invited by the agronomist to put the collective farm fields in order. We managed to survive for a while.

Then, our neighbours denounced us because we put up a fence! They were lazy; they had nothing, so they were happy to see it taken down “legally” by order of the local party leadership.

Heorhiy Hnatenko

The church books show that my great-grandfather, “Marko Hnatenko, a registered Kozak (Cossack) of the Pereyaslav Regiment marries the Kozak woman Fedorova”. The Soviet authorities forced my great-grandfather, his wife and their five children to leave their homestead near the old Cossack village of Vypovzky, near Pereyaslav. They were deported to the village of Vladislavovka near Novosibirsk, Siberia.

A year later, great-grandfather and great-grandmother died of typhus and exhaustion; the three older children managed to return; the two younger boys were placed in an orphanage. They wrote to each other until the beginning of the war. They wanted to return to Ukraine, but then all trace of them was lost. The mill, cattle and all the possessions were gone.

Nataliya Rudenko

My great-grandfather and his brother (Ivan and Oleksandr Fontaniy) lived on a farm in the village of Chapayevka, Makarivsky Raion, Kyiv Oblast. They were both dispossessed and deported to Norilsk, Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia.

My great-grandfather divorced his wife, my great-grandmother, so that she and the children would not be sent away with him. On the way to the Gulag, my great-grandfather died. His brother survived, and started a family in Siberia.

Anna Modla

My grandmother Teklya was married off quickly before she’d even turned 16 so that she could change her family name and not be sent to Siberia like her sister Olya. Later, Olya moved to Kazakhstan and only in the late 1960s was she able to return to her native village of Ratno in Volyn Oblast.

Lida Chaika

My grandfather had a shop that sold everything: salt, flour, eggs, etc. He had horse-drawn carts that travelled to and from the Polish border.

Those good-for-nothing bandits took everything: the house, the farm, the store. Grandfather and his family escaped, built a dugout in a forest with his own hands. The family lived there for quite a while.

Yana Hryhorieva

My grandparents were brutally dispossessed. Their land, house and all property were taken away. The family was forced to leave their home. For ten long years, they wandered around the countryside, staying with relatives and friends. Their son, my uncle, died at the hands of the Soviets.

Tetiana Andrushchenko

My great-grandfather was also dekulakized, declared an “enemy of the people” and kicked out of the house with his family. The worst thing was that his own son denounced him!

My great-grandfather couldn’t live with this thought and died the same day. All her life my grandmother bore the stigma of “daughter of an enemy of the people”…. even though she married a Soviet officer who was much older than her, and bore him two children.

Olha Drach

My great-grandfather was dekulakized because he owned a horse, a coat, some land, and had 14 children. He was considered a rich man!

He never joined the collective farm (kolkhoz) and refused to meet with kolkhoz farmers.

Uliana Bezkluba

My grandfather had a house and some land. He made an honest living by soaking hides that were then used to make shoes.

They took everything from my grandfather and sent him to Siberia with my grandmother, leaving four orphaned children.

Tetiana Prytula

My great-grandparents had 9 children. They had a cow and a farm, which were taken away when the collective farms was established all over the country. My great-grandfather also worked on the railroad and was able to buy land for his children. Everything was taken away.

Tetiana Kuyan

My great-grandfather Demyd owned a small estate in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. He had two sons, the youngest of whom was my grandfather. The Soviets labeled my great-grandfather an “enemy of the people”, threw him in the well where he drowned…

The eldest son was sent to Solovki prison camp; he was not allowed to correspond with his family and died of exhaustion.

My grandfather was “lucky”; he was sent to work at the construction site of the Dnipro Hydroelectric Station. My grandmother and her children went on foot to the island of Khortytsia, where my grandfather’s uncle lived - an old man in his 100s - the last living Cossack. She helped him run the household.

Grandmother secretly carried food to the prisoners working on the construction site. That’s how my grandfather survived. My father was the youngest of the children; he was born in 1929.

There were 12 orphaned children in my mother’s family. Both parents had died. The eldest was my grandfather Artem who worked very hard. He and his family had five hectares of land, a large farm: a mill, field horses, a phaeton, a carriage, a seeder, a plow, and lots of cattle.

My grandfather was a widower with two small children; my mother was the youngest. She was born in 1927. The neighbours were jealous, so they denounced the family. Local activists came and took away everything. They destroyed everything that they could not carry out of the house. My mother had a rag doll, which they pierced with large pins. They were looking for grain and food.

Liudmyla Oleinyk

My grandfather served during the war; his son was killed in the war. After the war, they came to dekulakize the family and ordered them to pack some things as they were being deported to Siberia.

While my grandmother was packing, my grandfather went to the district committee and asked them why they were doing this. He showed them his medals and scars (half of his abdomen was missing due to shrapnel wounds). They gave him a piece of paper allowing the family to stay, but all the land and property were handed over to the collective farm. This happened in Polissya region.

Danylo Pavliuk

Lubensky Raion, Poltava Oblast. My great-grandfather and his cousin were the only survivors. There were eight adults and children. Maybe more, but I really don’t know, because we have no documents.

A few days later, the villagers found the two small boys in the middle of the forest. The authorities registered them as orphans and sent them to an orphanage. My great-grandfather never talked about the Great Famine. He was afraid.

At the beginning of the war, my great-grandfather was taken to Austria by the Germans. After his release, he joined the Red Army and fought the Nazis. He said little about the war, and almost nothing about the famine.

The family never played around with food. In fact, all our neighbours lived the same way.

Oksana Stechyshyn

The repressive communist machine took the lives of my relatives. My great-grandfather was dekulakized and deported to Siberia with his wife and five sons. Only two sons returned, including my grandfather Stepan. He told me some stories about their life in Siberia. It’s impossible to remember this without tears.

The older boys had to work hard. While working at a felling site, a tree fell on grandfather’s older brother Pavlo (1921–1940). He was bleeding heavily and knew that death was near. But, he stretched out his hand and gave my grandfather the last piece of bread - that was all they were given to eat for the whole day. As he breathed his last, he said: “Take it, Stefan. I don’t need the bread anymore.”

There was nothing to eat. They gathered berries and plant roots. Some good people shared what little they had. At that time, my grandfather was nine years old. Bitter memories...

Olena Honchzrova

Village of Varvarivka, Kreminsky Raion, Luhansk Oblast. I remember my grandmother telling me that after a few calm years of NEP, the dreadful years of collectivization began.

My grandfather was called a kulak because he had land, cows, horses, a good house and a small barn. Everything was taken. They were left homeless with their children. I believe that they weren’t deported just because grandfather’s brother was a communist. However, the brothers weren’t on speaking terms. It was a family tragedy and a great secret.

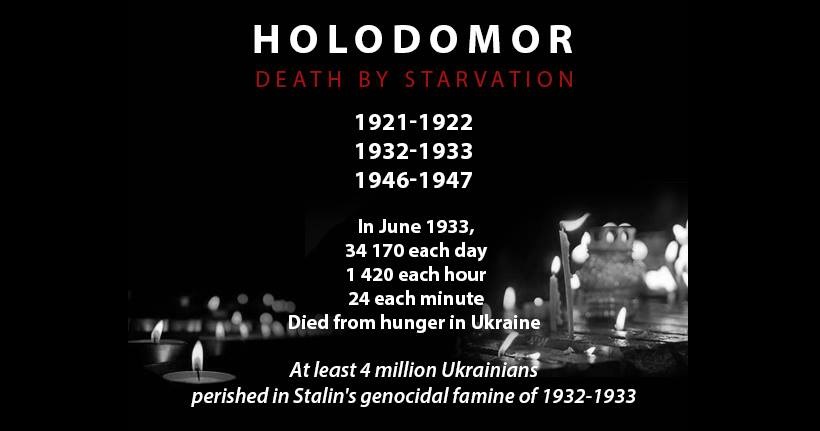

And then came 1933...

As part of a joint project with the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide - ‘Dekulakization: how the Stalinist regime destroyed Ukraine’s free peasant class’ - Radio Liberty asks families who know about their relatives being dekulakized to write and recount their stories. Important information to be included: names and surnames, age, number of family members and years of birth, children, place of residence (village, district, region), possessions (land, livestock, equipment, property), social status, hired workers, etc., as well as how they experienced and survived dekulakization. Facts, reactions and feelings are important. Please send all available photos and documents.

Please write to: [email protected]

TO BE CONTINUED…