At 5 a.m. that day, a group of Donbas Battalion fighters set out to recapture a checkpoint at Karlivske Reservoir. But, someone betrayed them. They fell into an ambush. A battle ensued, at the entrance to Karlivka, near the Druzhba café. Oleh and his comrades were trapped, surrounded on all sides.

It is part of the Plus 1 project created to memorialize the fallen Defenders of Ukraine.

Oleh Kovalyshyn. Warrior

Author: Volodymyr Yermolenko

A spacious room with a wall-hanging rug. His photo stands on the table: Montmartre, Paris, 2012, when he participated in the Chinese Go board game competition. Blue shirt, glasses, a pen clipped to his left pocket. A strong, direct gaze. Proud, but without sentimentality. More like an intellectual than a soldier.

Oleh was one of the first volunteer fighters to die in the Russo-Ukrainian war in Donbas. He was an intellectual who went to the front to defend his home.

He had poor eyesight: minus 8. But, he had something more.

“He was not a mere soldier. He was a warrior,” says his mother.

***

His mother uses diminutives, affectionately calling him Olezhenka, Olezhyk.

“He lived in the 10th century,” she says. A medieval knight.

Six years after his death, his room remains unchanged. He wasn’t very interested in material comforts: the furniture here is several decades old. A rug on the wall, a simple table and a chair. A bookcase. This room reflects a person who doesn’t care much about small things.

“I just can’t remove anything; I can’t throw anything away,” says his mother.

His possessions continue to occupy his personal space.

Books: Ancient Kyiv, Julius Caesar, Victories that could have been lost, Dictionary of Weapons. A figure of a medieval knight in armour, a figure of a Kozak on horseback. Wooden shields, that he used in medieval battle reenactments, and later - on the Maidan.

The most important item is his medieval suit of armour. It’s authentic, made of metal. A heavy iron sword, a heavy helmet with chain mail. Long before the war, before the real battles, he immersed himself in imaginary battles. His blacksmith friends made this medieval knight equipment for him. Before a bulletproof vest showed up on his bed in May 2014, Oleh wore chain mail and a helmet.

He was a warrior even before anyone in this country needed such a person. But, as it happened, we wouldn’t have survived without people like Oleh.

***

Things you cannot buy have value and are priceless. A warrior defends what is priceless.

A few centuries ago, a revolution took place in Europe. Instead of a warrior society, people formed a bourgeois society. The bourgeois ethos – commercial exchange, “a win-win game”. The objective - a mutually beneficial outcome for everyone. Some get more, some less - but there’s something for everyone. The bourgeois ethos has introduced moderation and pragmatism in our world. Instead of glory and victory on the battlefield, we seek mutual comfort.

A few centuries ago, a revolution took place in Europe. Instead of a warrior society, people formed a bourgeois society. The bourgeois ethos – commercial exchange, “a win-win game”. The objective - a mutually beneficial outcome for everyone. Some get more, some less - but there’s something for everyone. The bourgeois ethos has introduced moderation and pragmatism in our world. Instead of glory and victory on the battlefield, we seek mutual comfort.

But, there’s always a limit beyond which the bourgeois ethos turns our comfortable world into a world of horror. It’s good when we collaborate with others (goods, thoughts, emotions, information). But, we can’t share everything. There are things that cannot be exchanged or shared. Things you cannot exchange, buy or sell. Your family, the lives of your loved ones, your country. Values are priceless.

If a society has no soldiers, it forgets that not everything in life can be exchanged, that there are things that we must fight for to the bitter end. For some people, death is not a mere word. It’s death.

It seems that there are many real warriors among us. People who attended medieval tournaments for other reasons. Who went there with values. Values such as: “We shall fight to the end!”

***

Oleh had another hobby. He was an editor for the Ukrainian Wikipedia. One of its few invisible editors.

Oleh’s style and expressions can be found in many Wikipedia articles. He was interested not only in what was happening “here and now”, but also in what happened “there and then”. He wrote about ancient mythology, about Mesopotamia, about the Middle Ages. About the peoples of the Mediterranean Basin.

An American journalist who spoke to him in the early days of the war was fascinated by his erudition.

Oleh could live in his imaginary world and in the real world. He and his friends created a Fantastic Laboratory. They exchanged texts. Oleh attended reenactments of medieval tournaments and battles, for example, at Lubart’s Castle in Lutsk. He sewed his own suits, made his own medieval footwear. He called himself the Horseman of the Little Forest. When he went to war, he took the call sign “Raider”.

Despite his keen interest in the past, Oleh had an acute sense of reality, a sense of real injustice. During the Orange Revolution, he was an election observer. He was on the Maidan in 2014, in the most dangerous spots, protecting himself with his medieval shield. Early one morning, he was wounded on Hrushevsky Street; a deep wound from a stun grenade that tore away a huge chunk of flesh from his body. He walked home alone and then went to St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery to have his bandages changed. At that time, it was impossible and too dangerous to be treated by doctors.

He went to war not because he wanted to “experience something new”, not because of “youthful rashfulness”, not because he was searching for “new adventures”. He went to defend justice and protect his home and family.

“If we don’t stand together and close our borders, they’ll be in Kyiv in two weeks and will kill us all,” he said.

He felt that he had to defend his home. A knight from the Ukrainian Middle Ages. Or rather, from the Ukrainian Renaissance.

***

Oleh was killed on May 23, 2014 in Karlivka, Maryinsky Raion, Donetsk Oblast. He was thirty-five.

At 5 a.m. that day, a group of Donbas Battalion fighters set out to recapture a checkpoint at Karlivske Reservoir. But, someone betrayed them. They fell into an ambush. A battle ensued, at the entrance to Karlivka, near the Druzhba café. Oleh and his comrades were trapped, surrounded on all sides.

To this day, neither his body nor his remains have been found. His mother searched for him. She visited all the morgues in the area. For a long time, she hoped that he’d survived.

“It’s important for me to know how he died.” she says.

She went through two court trials - one to obtain a death certificate, the other - to obtain a Combatant Certificate.

This was his first battle. It was the 36th day of his war. The battle for Donetsk Airport would begin in three days.

***

She well remembers the day he departed to the front. It was April 16, 2014, the Holy Week of Easter. She meets Oleh in the alley leading to the metro.

“I’m meeting some friends,” he says. In fact, he wanted to say goodbye.

She returns home, goes into his room. A bulletproof vest is lying on his bed.

That evening, he boarded the train. There’s a little over a month left before that deadly battle in Karlivka.

***

People used to think that the word “warrior” was old-fashioned in the 21st century. It turns out that this was not the case. People used to think that mankind had become wiser and that we’d soon be living in eternal peace. It turns out that these were pipe dreams.

He who lives only in the present moment lives in an illusory world. Because nothing is as illusory as a moment that comes and immediately disappears. He who thinks in terms of centuries and millennia and not in days or years is more sensitive to the heartbeat of time. And it so happened that a young man in glasses and medieval armour felt the approaching storm more acutely than his carefree peers.

One of the uplifting things is that people like Oleh have appeared in the history of our country. People who sacrifice their lives. This is a debt that we’ll never be able to repay. People who have given the word “warrior” meaning. People who have taught us to remember that there are so many priceless things in life… things that we must stand up for and protect with indefatigable resolve.

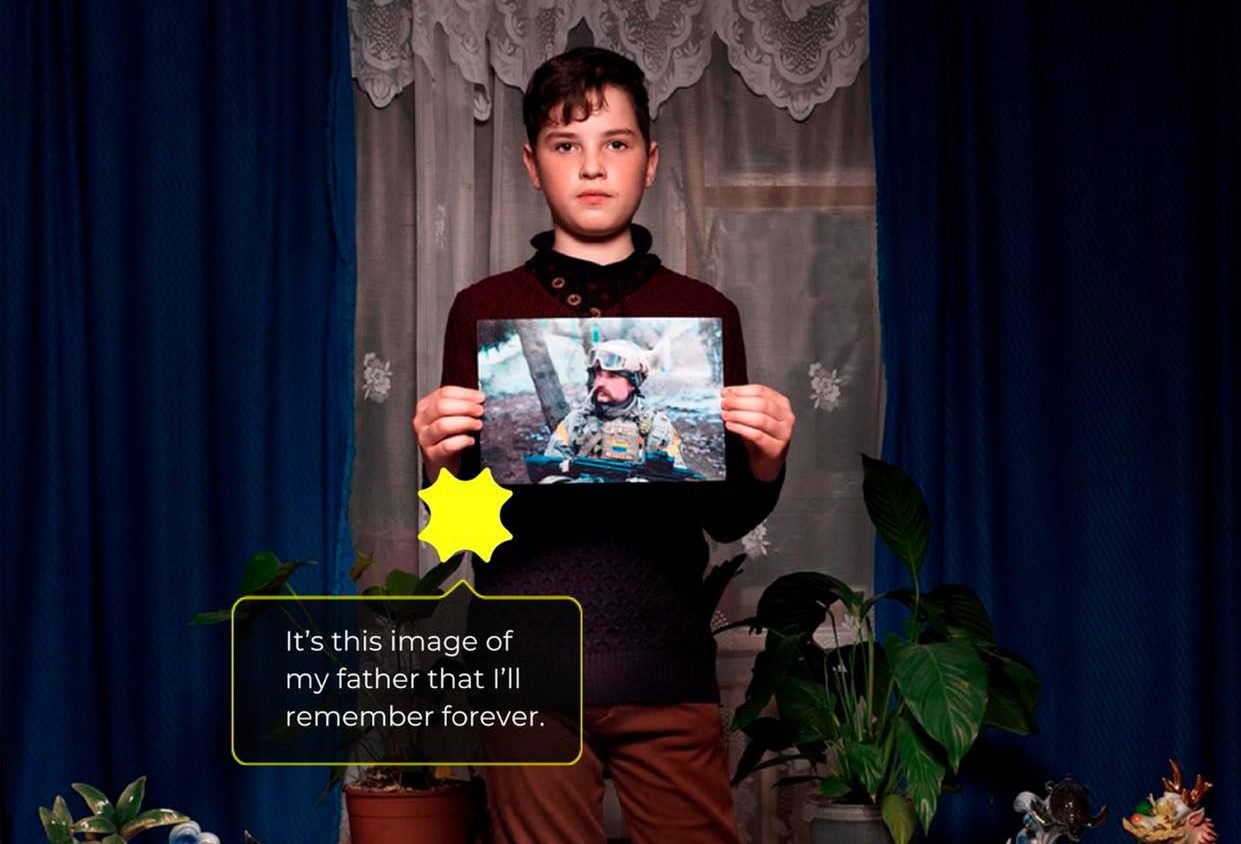

The project is built around 22 individual exhibition stands. In iconic and powerful moments captured by a photographer’s camera – Youry Bilak, a Frenchman of Ukrainian descent – Ukrainian families tell the stories of their loved ones – Ukrainian soldiers who perished in the war. Each narrative, each individual is but one small grain, one tiny unit of a module in a living organism. By telling his story, we bring him back to life.

Each family chose an object that most reminds them of their departed: a father’s jacket, a guitar, a suit of medieval armour, a book. These family artifacts reflect a living continuation of the departed loved one. Ukrainian artists, intellectuals, and journalists were invited to create original texts about each soldier.