And it was not only Germans who made an impact on eastern Ukraine during the Industrial Revolution of the 18-19th centuries. Both regional capitals of Ukraine's Donbas appear to have British roots: Scottish-born Englishman Charles Gascoigne is believed to be the founder of Luhansk (1795) while Welshman John Hughes founded Donetsk in 1868.

Lured by prospects of religious freedom and profits at the epicenter of the Russian Empire's Industrial Revolution, Germans, British, Belgian, and other Europeans forged a new home for themselves in the Wild Field of Ukraine's steppes. Their love story with the new homeland was cut short: the resettlers were destroyed in the class purges of Soviet Union and upheavals of WWII.

Wild Field

Up until the late 17th century, the huge steppe of modern Ukraine’s southeast was the country’s Outback and was often referred to as Dyke Pole, or the Wild Field. The lands had a rather sparse population of Cossacks, Ukrainian peasants, and sedentary descendants of various once nomadic peoples who had earlier ruled these steppes for many centuries.

The Pereyaslav Treaty of 1654 between the Hetmanate -- the Ukrainian Cossack state -- and Moscow allegedly secured the Tsardom of Russia’s military protection for the Hetmanate in exchange for allegiance to the Tsar.

Throughout the next century, Russian policies eventually led to the demise of the Hetmanate, the dissolution of the Cossack Host, and the annexation of the Cossack territories by the Russian Empire throughout 1764-1775.

Meanwhile, the late Russian imperial and subsequently Soviet propaganda presented the treaty as an act declaring the unification of Ukraine and Russia, which it wasn’t.

The empire had founded multiple cities in the “Wild Field.” In practice, it initially was just constructing some military or industrial facility with basic infrastructure within an existing Ukrainian settlement or next to it. That's why the official foundation dates of many cities in Ukraine are questionable up until now.

European settlers and industrialists

At the end of the 18th century and further on, multiple European industrialists sought to build their factories and coal mines in southeastern Ukraine, particularly in the coal-rich region that became historically known as the Donets Basin or Donbas for short. As well, Russia tried to resettle as many European settlers to the Ukrainian steppes and bring as large a workforce from Russia as possible.

This process unfolded not only in the modern Donbas but throughout the entire southeast of Ukraine.

For example, in 1789, a combined Cossack and Russian force conquered Khadzhibey, an Osman fortress port town that was founded by the Great Duchy of Lithuania in the early 15th century which fell under Ottoman rule. And in 1794, Russian empress Yekaterina II ordered to build a military harbor and merchant's pier in Khadzhibey.

The city got a new name of Odesa, and a number of high-profile Europeans in Russian service were involved in the construction of the city. Among them were Flemish engineer and architect François-Paul Sainte de Wollant who redesigned the city, Odesa's first mayor was Italo-Spanish military officer Josep de Ribas y Boyons, the first Russian governor of Odesa was French statesman Armand-Emmanuel du Plessis, 5th Duke of Richelieu, who later was a prime minister of France during the Bourbon Restoration.

Since the Donets Basin coalfield was of prime interest for industrialists, throughout the late 18th and entire 19th centuries, many European businessmen founded factories and coal mines in the area, often bringing specialists and workers from their countries and drawing a workforce from the nearby local settlements and from across the Russian Empire.

The workers' settlements often grew in population, becoming towns or cities. On the other hand, the Russian Empire also facilitated the immigration of farmers, primarily from Germany, in order to give a boost to local agriculture.

British roots of local capitals

Both local capitals of the Donbas region, Luhansk and Donetsk, were kickstarted as industrial centers by the British.

The city of Luhansk emerged in 1795 as Luhansky Zavod ("Luhan River's Factory") - a metal factory, founded by English industrialist Charles Gascoigne, with a settlement for its workers adjacent to Zaporizhzhian Cossacks settlement Kamianyi Brid. Both settlements merged about 90 years later in the city of Luhansk.

One of the first streets in Luhansk was Angliyskaya ("English St"), which became home for the families of the factory's management and other foreigners. Among those was prominent Russian lexicographer Vladimir Dal, who was born to his Danish father and German mother in Luhansk in 1801.

Another European name well known in the history of Luhansk is Gustav Hartmann, the German locomotive builder who founded the locomotive works in Luhansk in 1896. The factory still exists and had worked up until the Russian occupation of the region in 2014.

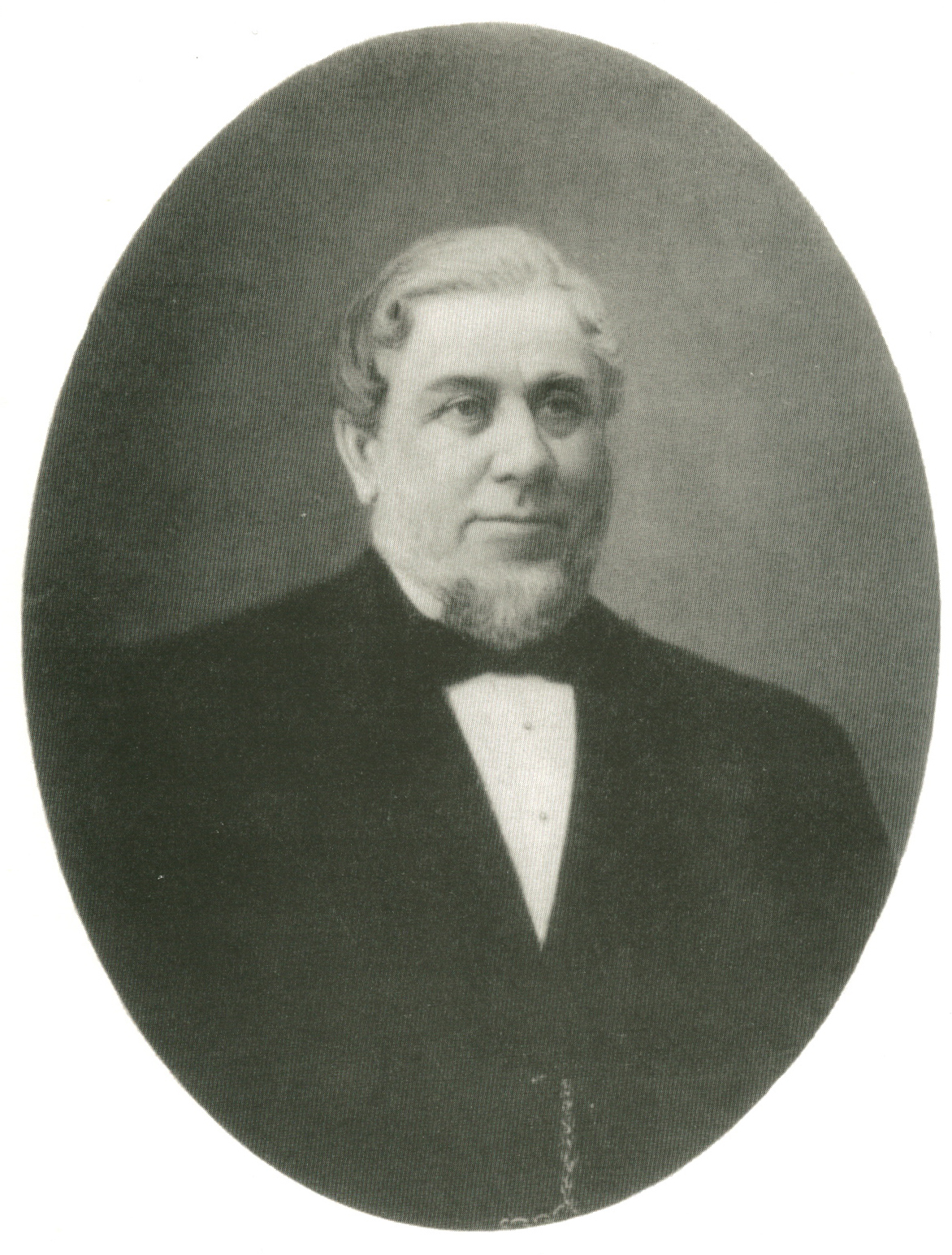

Donetsk was founded in 1869 as Yuzovka by John Hughes, a Welsh businessman, who built several coal mines and a steel plant with accommodation and some basic infrastructure for his workers in the area of Zaporizhzhian Cossacks' settlement Oleksandrivka (now part of Donetsk).

The name Yuzovka is derived from the Russian pronunciation of Hughes' last name, so technically it should have probably been spelled as Hughesovka in English.

Hughes had also brought with him some workers from the mining villages around Merthyr Tydfil, a Welsh town.

Later Belgian engineers Bosset and Gennefeld built in Yuzovka an iron foundry, a mine, and a mechanical plant, which produced steam engines, boilers, winches, and pumps for mines.

The Soviets renamed the town Stalin in 1924 to honor Josef Stalin, a few years later the city became Stalino, and amid the Soviet de-Stalinization after the communist dictator's death received its current name Donetsk based on the name of the Donets river which gave the name to the entire region.

More industries

In 1887-1889 at the heat of the industrial revolution in the Russian Empire, the South Russian Dnieper Metallurgical Society with its founders from Belgium, Poland, Germany, and France built a large metallurgical plant in Kamianske in modern Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, which gradually turned a small town on the western fringes of the Donets Basin into an important industrial center.

Under the Soviets, the city bore the name of Feliks Dzerzhinsky, architect of the Red Terror, yet in 2016 the Dneprodzerzhynsk returned to normal and became Kamianske again.

In the late 19th century, Belgian businessmen Louis Lambert, Paul Noble, and Joseph Siesel, who represented the interests of three different Belgian industrial groups, established the Anonymous Society of Donetsk Glassworks. The activities of the company de-facto transformed the village of Kostiantynivka in Donetsk Oblast into an industrial city, establishing a full-cycle iron production with an open-hearth furnace, cast iron, and steel production facilities. They also built glass, ceramic and chemical factories.

In 1892 in Luhansk city of Lysychansk, the Donetsk Soda Plant built by the Russian-Belgian company Lubimoff, Solvay and Co, started producing soda ash and later launched the production of other chemicals.

The infamous town of Bunge or Bunhe in Donetsk Oblast was founded with the Bunge Mine laid in 1908 by the Société métallurgique Russo-Belge - Russo-Belgian Metallurgical Society, named after the Society's CEO Andrey Bunge. As the mine was hijacked by the Soviets, they renamed it Yunkom ("Young Communard") in 1924, assigning the name Yunokomunarivsk derived from the mine's new designation to the mining settlement of Bunge, which later in 1965 received the status of a city.

The town and the mine are known for a Soviet underground nuclear industrial explosion carried out in the mine in 1979. Occupied by Russian-hybrid forces, the city received its original name in 2016 as the Ukrainian parliament returned historical names to a number of cities and villages under the decommunization law. In 2018, the occupation administration shut down pumping facilities of the potentially hazardous mine which led to its subsequent flooding, and for now, there is no reliable information on the radiation situation around the town.

Not just capitals, not just industrialists

Here are just a few of countless examples of the European presence in the region.

In the second half of the 18th century, the Russian authorities allowed Serbs, Bulgarians, Moldovans, Poles to settle in the lands of Zaporozhian Cossacks between the rivers of Luhan and Donets, which became known as Slovyanoserbia with Bakhmut (now in Donetsk) as the major city of the area. The colonists received a monetary incentive and land from the Empire. The only trace the settlers left is the name of a settlement in Luhansk Oblast, Slovyanoserbsk.

In 1869, an Evangelical community of Germans founded the village of Ostheim (German for Eastern Home) in the south of what later became Donetsk Oblast. In 1935, the Soviet authorities renamed the place Telmanove after the German Communist Ernst Thälmann.

After WWII, the Soviets deported the local Germans from their village and settled in their homes the Boyko Ukrainians who were deported from a village in the area of the West-Ukrainian city of Drohobych amid the Soviet-Polish exchange of territories in 1951. In 2016, the now Russian-occupied village became Boykivske amid the decommunization after the Boyko deportees.

Founded in 1885 as Liebenthal (German for Valley of Love), the small German Catholic village in the south of modern Luhansk Oblast became Liubyme ("the favorite one") in 1927. As of the 1920-1940s, almost all of its 500 inhabitants were German. Founded in 1870, the Lutheran German village Marienthal became Karla Marksa ("of Carl Marx") under the Soviets, finally, it was decommunized to Myrne ("peaceful") in 2016.

The German populations in the territory of modern Donetsk oblast were so numerous in the first decades of the 20th century that the so-called Luxembourg German district existed in the south of modern Donetsk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts in 1925-1939. It included some 40 German villages with the German population of around 20,000 (around 8% of the district's entire population).

Among the German settlements in what is now the Donetsk part of the district were the villages of Elisabethdorf founded by 1825 by 35 German families from Baden, Hessen-Darmstadt, and Alsace; several colonies of German Mennonites such as Schönthal (founded in 1838, now Novoromanivka) and Friedrichsthal (1852, now Fedorivka), Yamburg village founded in 1836 by Holland settlers. and many more.

The Soviet authorities first "dekulakized" the richest settlers in the 1920s, then during and after the Second World War, the Communists deported most of the ethnic Germans from Ukraine and the rest of the European part of the USSR to Kazakhstan, Ural, and Siberia.

Tragic finale

Not much remains of the German, British, and Belgian legacy in the Donbas. Most foreign businessmen left the Russian Empire either after the crisis of 1905 or after the 1917 revolution and hostilities that followed. In the 1920s, the Communists quickly seized all private enterprises and saw any businessman as an enemy of the proletariat. Meanwhile, the German rural settlers faced repressions in the 1920-1930s and deportations amid WWII.

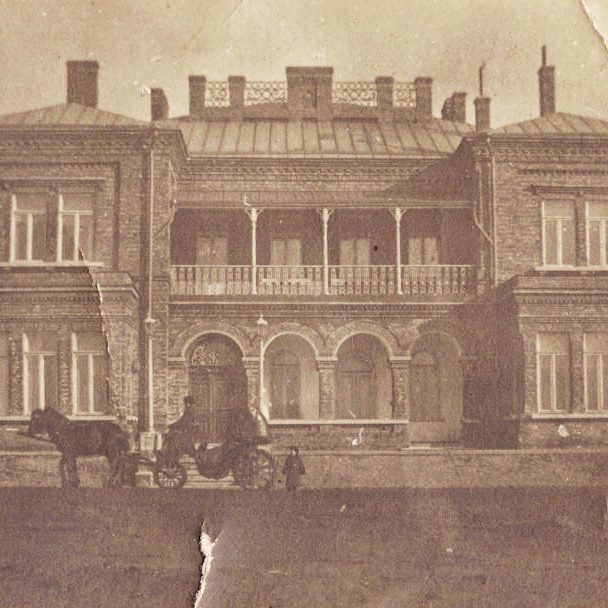

For example, after John Hughes' death in 1889, the Hughes family lived in Yuzovka up until 1903 when they moved to Saint-Petersburg and later to England. An Englishman named Anderson who was the manager of their factory lived a few more years in their house, then he handed it over to the new manager, Russian Adan Sinitsyn who occupied the mansion up until 1918 when Bolsheviks "nationalized" it, using it as a shop for producing cheese.

The industrialists and settlers didn't leave behind any buildings of sophisticated architecture or any prominent monuments. For now, there are some old dilapidated houses that were offices of the enterprises or hosted workers and managers, ruins of old industrial installations, and that's it.

The local authorities in the Donbas didn't put much effort into restoring and preserving the European legacy of the region both under the Soviets and in the first 20 years of the Ukrainian independence. And with the Russian occupation of significant parts of Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts, including the regional capitals, even less hope remains that something related to the European legacy of the region would be preserved.

German-founded New York in Donetsk

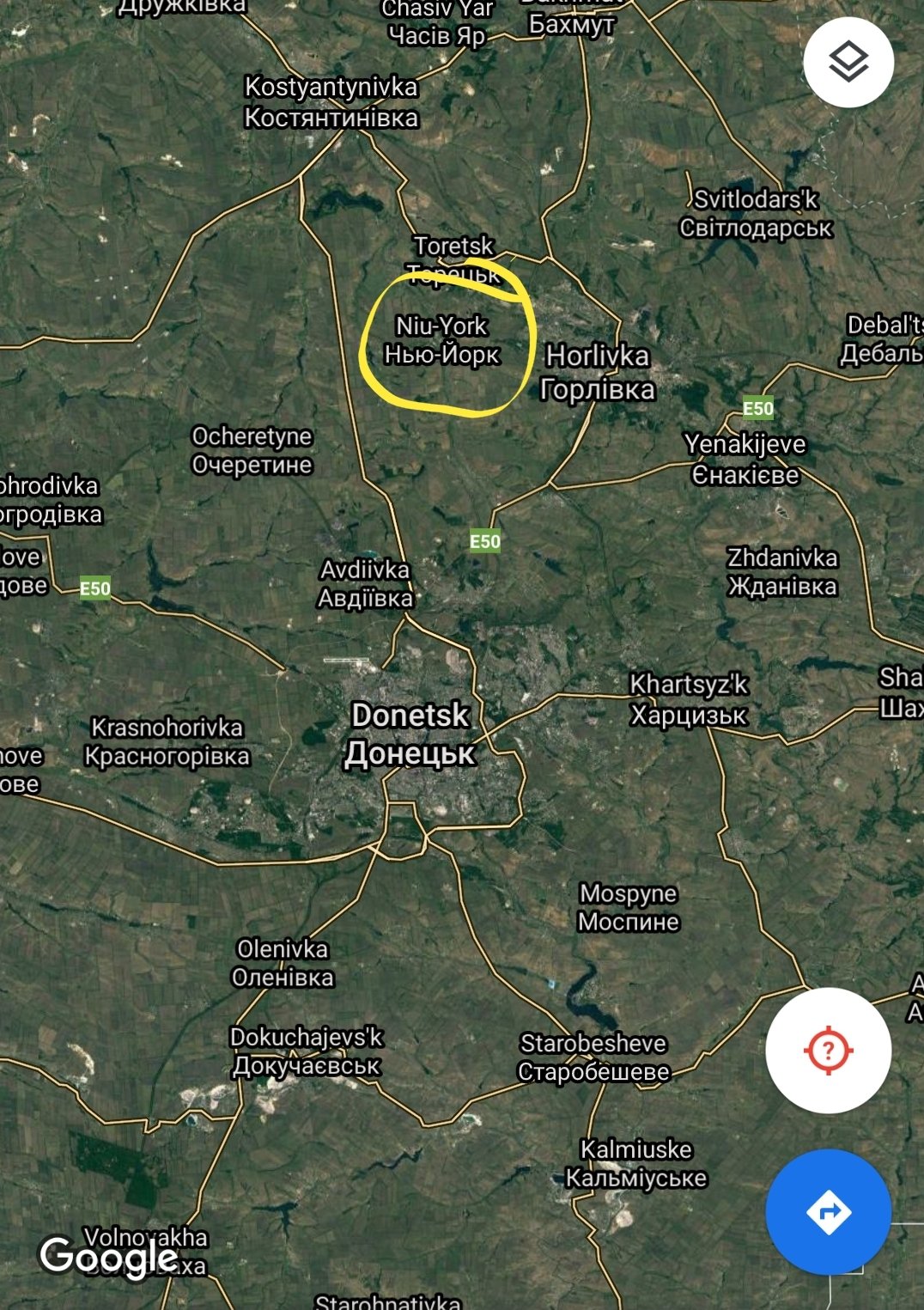

And what about the New York of the Donbas and its American name?

The settlement of New York emerged in the east of Yekaterinoslav Governorate of the Russian Empire in the mid-19th century. In 1892, German settlers, Mennonites and Lutherans, bought land plots of the settlement and nearby villages and established their colony with brick and roof tile production.

In 1894, the German engineer Jacob Niebuhr built a machine-building plant in New York for manufacturing agricultural machinery. In 1941, a few months into the war with Nazi Germany, the Soviet authorities deported all Germans still living in New York to Kazakhstan.

But why "New York"? This question puzzles local historians and ethnographers. As the secretary of the settlement council, Tetiana Krasko said in her comment to RFE/RL, the maps of the mid-19th century mark the settlement as New York before it became a German colony, thus the origins of the name remain unknown.

"The generally accepted version is that the Germans did name it," explained Tetiana, "Anecdotes have it that one of them had an American wife and he named the settlement in her honor, or that some of them used to visit America, liked New York and wanted to make his town industrial. The third version is that the Mennonite Germans named their new places of residence by adding 'new' to the name of theit hometown, and there is a town of Jork in Germany," (the last version doesn't explain why they would use the English word new instead of the German neu, - Ed.).

In 1951, in the early years of the Cold War, the Soviet authorities decided that having such an American name in Ukraine wasn't in line with communist party's policies, so the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR renamed New York as Novhorodske. The made-up name Nodhorodske means "Nodhorod's" or literally "new city's."

Now, on 1 July 2021, Parliament officially renamed the urban settlement back to its original name. However, a setback remained, New York under the official rules of transliteration from Ukrainian is Niu-York.

Meanwhile, the US Embassy has already congratulated the residents of "New York, Donetsk Oblast,"

Congrats to the people of New York, Donetsk Oblast, on the return to their town’s historical name by cross-faction consensus in the Verkhovna Rada! Another reason to celebrate our close ties. We’re big fans of your new/old name!

Read more:

- The rise and decline of Donbas: how the region became “the heart of Soviet Union” and why it fell to Russian hybrid war

- Ukraine’s European heritage is in its language’s DNA

- Russia’s occupation of Ukraine: a historical and centuries-old process

- FC Zorya Luhansk: A story of war, financial destitution, and absolute fighting spirit

- Six challenges Ukraine’s national state faced before Euromaidan

- 12 facts about the Donbas that you should know

- How the UNR Army liberated the Donbas in 1918

- On the ancient pillars of Ukrainian democracy: Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution of 1710

- How Moscow hijacked the history of Kyivan Rus’