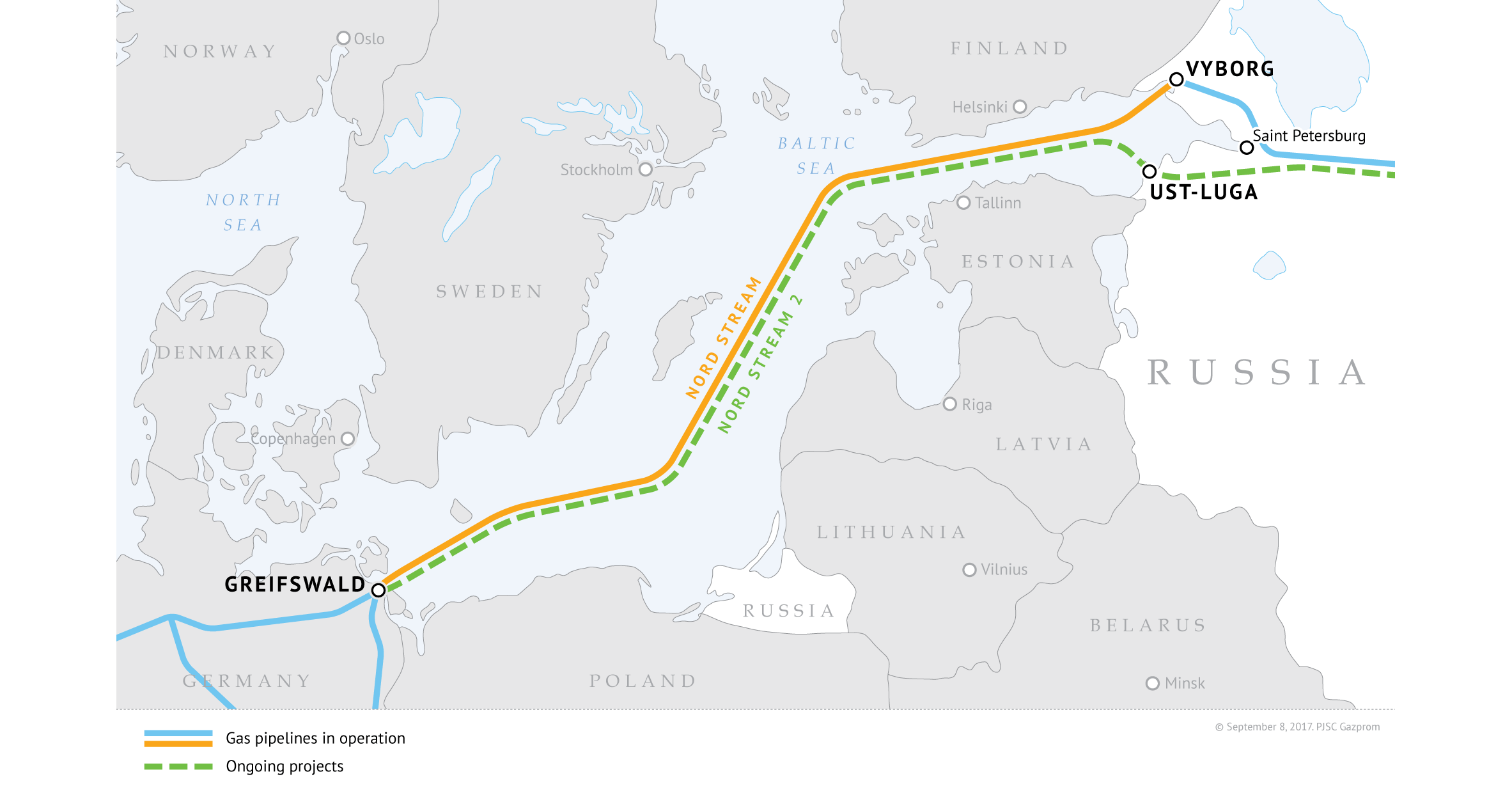

Whether or not the Nord Stream-2 gas pipeline will be completed is no longer a relevant question. The key question in the coming months, and possibly years, will be another: under what legal conditions will it be allowed and then operated? Addressing this issue will determine the fate of gas transit via Ukraine in the future.

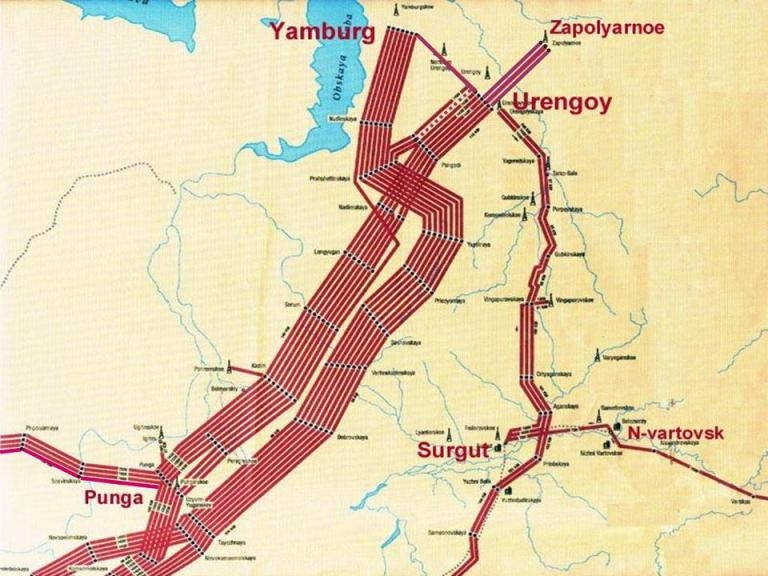

Historical experience shows that the US will not be able to prevent the project with sanctions. Under Ronald Reagan´s and Margaret Thatcher´s rule, the United States and Britain also imposed sanctions on the construction of Progress and Soyuz transit pipeline systems from the Soviet Union to the Western Europe. Even then, during the Cold War, these pipelines caused tension and dispute between the Western Allies, especially between the United States and West Germany and France. But even then, Siberian gas broke through the Iron Curtain.

Today’s US President Joe Biden probably remembers the lesson from this story, because he was already a member of Congress at the time and was involved in external affairs. After arriving at the White House earlier this year, his administration realized that it could for some time postpone the construction, but that would not stop the work. Therefore, it was forced to take into account a much higher risk: what will happen if the pipeline is completed at odds with sanctions (albeit with some delay), but the result will be a long-term deterioration of the relations with Germany. With a country which, along with Britain, is a key partner of Washington in Europe.

Therefore, Kyiv should not harshly criticize Biden’s decision on Nord Stream 2, as it can only seriously and permanently damage relations with the United States. In addition, the sanctions have not yet been completely lifted and Biden is clearly waiting for the situation in Berlin autumn after the elections.

What should Ukraine do in this case?

It would be much more productive for Kyiv to focus on discussions with the US, Germany, Brussels and other European partners regarding the conditions for allowing the Nord Stream-2 gas pipeline to operate in the context of maintaining transit via Ukraine.

I would like to stress two important points.

The first is directly related to the fact that the key transit route through Ukraine to Europe leads to the border with Slovakia, the border points Uzhhorod – Veľké Kapušany. Gas is currently being transported through them, which Gazprom plans to transfer to Nord Stream-2. It should be noted at the outset that many, especially in Berlin, mistakenly claim that this new pipeline needs to supply Germany with gas following the impending closure of nuclear power plants. That is not entirely true. Much of its annual capacity – 55 billion cubic meters – is dedicated to Central and Southern Europe, including Slovakia, Austria, and Italy. And this is exactly the gas that is now coming to these regions via Ukraine.

In fact, we have very different situations here today. Uzhhorod has a contract with Gazprom until 2024, but the Slovak Velké Kapušany has a contract until 2028. If Berlin claims that its new pipeline should not stop transit through Ukraine, it must primarily support the extension of the Ukrainian-Russian transit agreement through Uzhhorod for the same period of time as Gazprom’s subsidiary Gazpromexport has with Slovak operator. If Moscow does not agree, it means that there is a danger for Ukrainian transit. Therefore, Berlin must guarantee Ukraine compensation for all losses associated with these threats.

The second point concerns general EU legislation on gas transmission. The main rule is not only to separate the pipeline operator from the gas supplier or trader, but also to ensure competition through third party access to the pipeline. In other words, one supplier cannot block all the capacity of certain transmission pipelines.

However, as the controversy over the German Opal pipeline, which continues to transport Gazprom gas, which has been supplied to Germany via the Nord Stream-1 pipeline for several years, shows, there are many exceptions to these rules.

Both of these new pipelines will, in fact, only redistribute the gas flows that now run through Ukraine.

For this reason, it is necessary to adjust the European law: due to changing of import route and point, existing gas transit pipeline cannot be disabled at the expense of another route. In particular, when it comes to changing gas import corridor from the same supplier, from the same production region, the volume of supplies will not increase significantly and supplies will go to the same regions of the European Union. And this rule should be directly related to the rule of third party access , as well as their downstream distribution infrastructure – in the sense that this rule cannot be revoked when the pipeline and point are filled due to these changes in gas import flows.

Ukraine has the right to request such changes to the rules on the basis of the Association Agreement with the EU. It is therefore possible to create a functioning and legally formalized mechanism that will allow for the long-term protection of Ukraine’s interests, in order to maintain a significant amount of gas transit via Ukraine.

Related:

- What Europe can learn from Ukraine’s gas woes with Russia

- Time to stop Nord Stream 2 now: open letter by Ukrainian politicians, leaders

- Mitigating the Nord Stream 2 impact on Ukraine

- Biden may lose ability to play around with Nord Stream sanctions: interview with Lana Zerkal

- Everything you wanted to know about Nord Stream 2 but were afraid to ask