After long years of Soviet oppression and neglect by various governments, tectonic changes are underway in Ukrainian culture. Grassroots cultural initiatives are starting to receive state support -- and the result is bearing fruit.

How Soviet Union policy totally distorted Ukrainian culture

Initially, after Ukraine declared Independence, the importance of cultural policy was underestimated. So were the cultural figures. Their only option was to follow the official party line or to be independent and conceal their work deep underground. This manner was left from the Soviet Union. During the Soviet era, cultural policy served the purpose of propaganda. To veer from this path, artists of all fields would place themselves in serious danger by the State apparatus. In different periods, the level of threat by the Soviet State for independent writers, poets, artists, performers, and many others was severe. Some cultural figures managed to subtly integrate symbolic narratives into their works. However, it was impossible to do so on the issue of national identity. The apparatus was constantly monitoring for any hint of national independence or freedom of thought. Dozens of prominent cultural figures were subject to harsh measures of repression during Stalin’s Great Terror. In Ukraine, from the 1920s to the 1930s, an entire generation of artists was either exiled to Siberia or liquidated.

How culture gained freedom, but no support

“The mandate of the program to help and support cultural policy reforms in Ukraine has been effectively covered in dust, in part due to the sincere misunderstanding by domestic cultural officials of what this cultural policy is and why it is needed.”Botanova summarizes the dilemma in simple terms, saying that as of 2010, the cultural sphere in Ukraine has clearly been divided along two lines – State and Non-State (official and non-official). The State (official) line that has controlled the funds in the State’s budget has been stymied by a large-scale network of corrupt cultural institutions inherited from the Soviebt Union. While the non-State (non-official) line has been led by oligarchs. Cultural journalist Kateryna Stukalova describes the period in much the same way, saying that in the 1990s it became clear to cultural figures that interaction with simulated State institutions was meaningless and ineffective. Meanwhile, the consumer market could not support the existence of artists, even for mere survival.

“The inevitable drift of Ukrainian art into the arms of oligarchic clans and its incorporation into a new quasi-feudal social structure began.”Some of the oligarch projects were and still are quite successful; for example, the renowned PinchukArtCenter, an international modern arts center. Founded in 2006, the center is a project of the Victor Pinchuk Foundation. As its name connotes, the foundation was established by media magnate Viktor Pinchuk, among the richest Ukrainian oligarchs. At the same time, with some exceptions, the Ukrainian cultural field has become apolitical.

“As long as contemporary art existed in its parallel world, without making any articulated demands from the State, demonstrating self-sufficiency and almost not commenting on political processes in artistic language, the State has learned to use its autonomy and lack of claims to budgetary resources. There were two parallel worlds -- the modern art process with its own resources and survival strategies and the State apparatus -- a decorative facade that simulated ‘culture management’ and is guided by completely inefficient, disconnected from reality, and opaque principles of activity,” Stukanova wrote.Among the prominent cultural events of the first decade of the 2000s, Botanova mentions the formation of a new staff complement for the Kyiv Arsenal National Art and Culture complex. The new team’s goal was to make the center the Ukrainian Louvre. The opening of the art center Isolation in Donetsk was also an important event. The center was moved to Kyiv with the onset of the war in Donbas. The original center in Donetsk has been turned into a concentration camp of the Russia-backed, self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR).

- Read also: Three warders who tortured prisoners in occupied Donbas “concentration camp” ID’d as Russian citizens

Development after the Euromaidan Revolution

The first results and disappointments

- Providing a favourable environment for the development of intellectual and spiritual potential of individuals and society;

- Ensuring wide access for citizens to national cultural heritage;

- Supporting cultural diversity; and

- Encouraging integration of Ukrainian culture into the world cultural space.

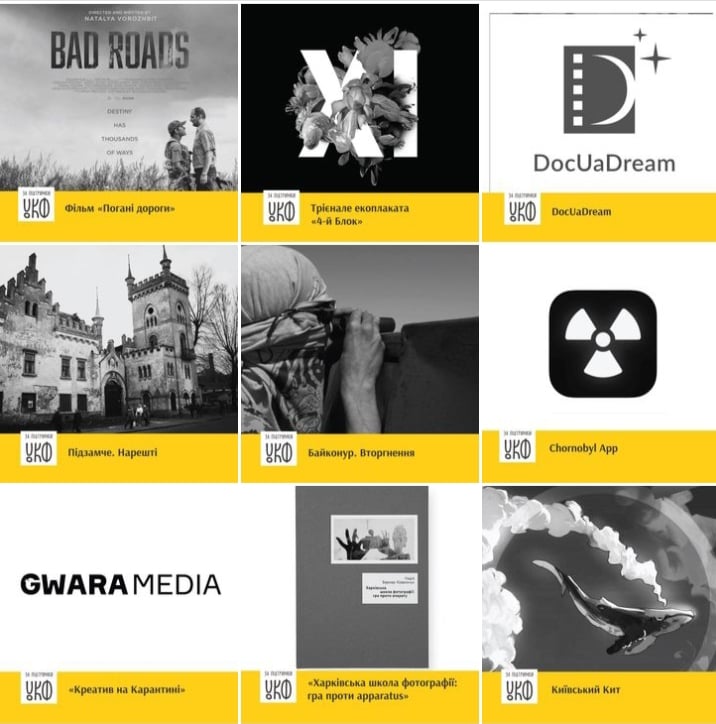

“Our delight over the new transparent cultural institution that was finally opened in Ukraine was short-lived,” says the statement released by the film festival Kharkiv MeetDocs after it was rejected in funding this year.According to the statement, the total audience of the festival is 4,000,000 viewers, this year it received 450 points out of 500 possible from UCF, but eventually was not even accepted to the negotiation procedure. Similar things have happened to a number of known initiatives. Among them Mute Nights Festival, 10th Festival of silent cinema and modern music, Dovzhenko Centre, cultural institution keeping Ukraine’s cinema legacy, 5th cinema festival Kyiv Week of Critics, V Forum of Creative Industries, and others. Soon, it will be visible whether such a recent turn is indeed the beginning of serious problems. However, so far it is clear that the very existence of the UCF has laid the groundwork for the ongoing development of Ukrainian culture. After long years of Soviet oppression and neglect by various governments, culture has finally made it onto the agenda.

This publication is part of the Ukraine Explained series, which is aimed at telling the truth about Ukraine’s successes to the world. It is produced with the support of the National Democratic Institute in cooperation with the Ukrainian Crisis Media Center, Internews, StopFake, and Texty.org.ua. Content is produced independently of the NDI and may or may not reflect the position of the Institute. Learn more about the project here.

Read also:

- New Lviv Museum showcases clandestine avant-garde art outlawed during Soviet era

- Recovering the forgotten names of the Ukrainian avant-garde

- Who's winning on the Ukraine-Russia historical narrative battlefield?

- A taste of Ukraine’s poetic Renaissance executed by Stalin

- Modernized past: how today’s Ukrainian culture combines tradition and modernity