Volodymyr Rybak was kidnapped on April 17, 2014 in Horlivka right after a pro-Russian meeting organized to support the town mayor, Yevhen Klep. Rybak was trying to take down the flag of the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic” (“DNR”) from the town council building. On April 22, his mutilated corpse was found in the Kazenny Torets River near Raihorodok, Donetsk Oblast.

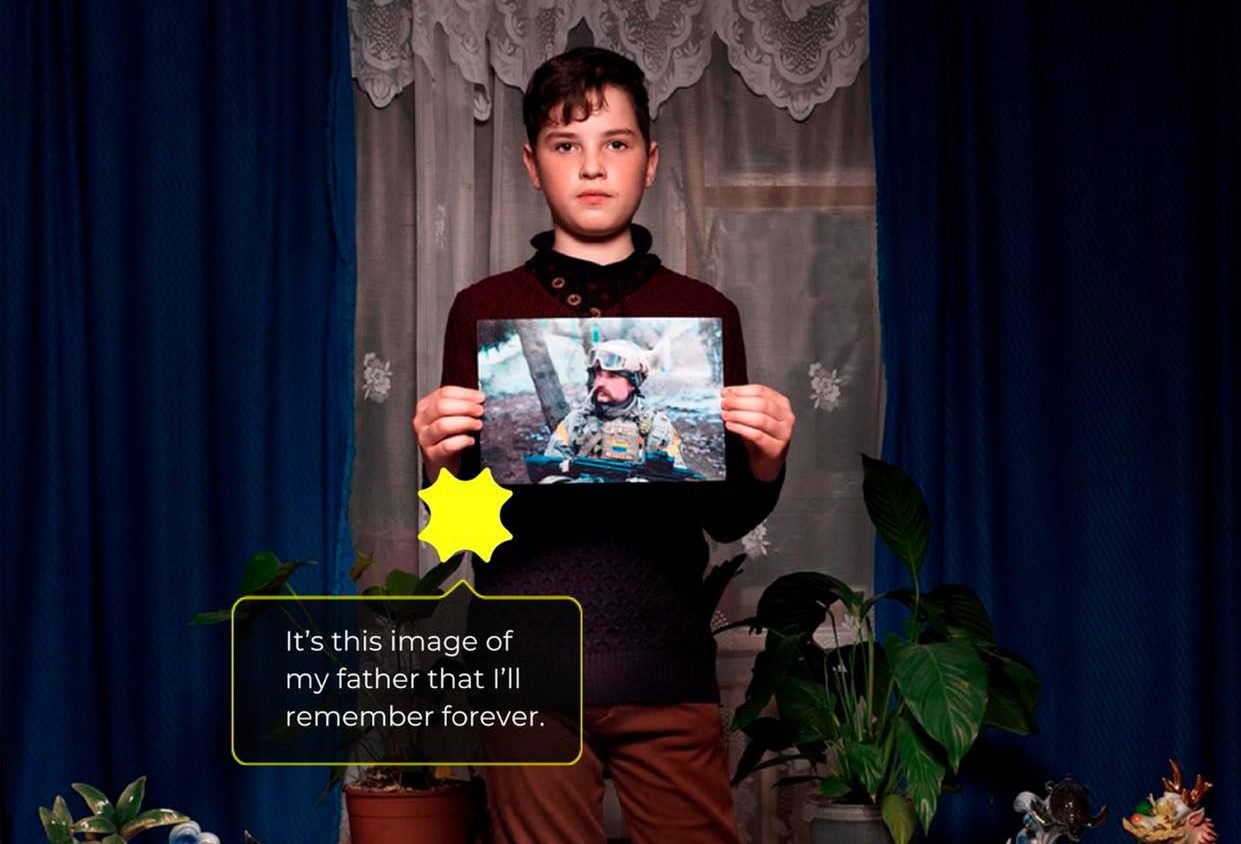

It is part of the Plus 1 project created to memorialize the fallen Defenders of Ukraine.

Volodymyr Rybak

Author: Tamara Horikha Zernia

“He was an ordinary man in every way! You know what I mean? He wasn’t a misfit, or a saint, or an idealist, or a hapless dreamer. Of all the words one might use to describe Volodymyr Rybak, “helpless” isn’t one of them.”

I’m speaking with his wife, or more specifically, his widow, although Olena remains his wife, even after six years of widowhood, a fact we accept without judgment.

Our conversation proceeds calmly and naturally, although it’s obvious that some words keep re-appearing, causing them to lose their impact from overuse, powerful emotions now waning, leaving us with dry bits of information.

There is the explanation that he disappeared at such and such an hour, encounters with thugs and criminals at this and that hour. The search for witnesses and contacts.

“They wanted our home to be transferred to them. I told them, fine, but before I sign it over, just let me speak with him.”

Hope, hope, hope. Identifying his body, then the funeral. And now life without him. Hopelessness.

Olena has wrapped herself in protective armour which cracks and fragments only once, namely when I ask about the photograph. The photo ostensibly captures the decisive moment of Rybak’s arrest. He is barefoot, blindfolded, paraded through the crowd.

“What do you mean? That’s not him!” Olena bursts out. “Never, never in his life would he ever allow himself to be detained by two strangers. Never in his life would he permit himself to be led like a calf with a rope around his neck. He would have fought back, he would have slit their throats, left them as corpses, but he would never surrender. You don’t understand who he was…”

I’m confused. As are many other Ukrainians who learned about Rybak only in connection with his tragic murder. Many had no association with him as a living person apart from our knowledge of his martyr’s death. However, it became very important for me to know who he was in his lifetime.

Memory is the most fickle thing in the world. By nature, we are hardwired to forget; we are Universal Champions at psychological repression or displacement of one idea for something more acceptable. We masterfully create parallel realities, where every little pebble has its predictable and designated place. But then, what is one to do with those small stones that don’t fit into their designated places?

-“Tell me about him. The way he really was.”

-“He was very ordinary…”

A tall, extremely charismatic and handsome man, a “head-turner” as they say in English. In Ukrainian, it means he was a man who always and everywhere commanded attention. He had looks that could turn heads, and he would surely enjoy making women swoon, but he was only enamoured of one woman, his wife and the mother of their daughter. She was the favourite of every toast he’d ever make at any gathering, even in only male company where the ladies were absent. Only for her, he established an idyllic and peaceful home, in which every nail was hammered into place by his hands.

With those hands, he could do anything he set his mind to; no technical problem was too difficult for him to resolve. He successfully mastered both the tools and materials for construction – drywall, ceilings, walls, furniture and appliances; everything ran like clockwork. He received awards from hospitals and rest centres as the most accomplished and active participant in competitions and contests. He was very happy.

He had fourteen years of experience in criminal justice. This is a career that leaves no one with any illusions about the nature of crime. There are no naive crime fighters, especially officers in Horlivka. He knew the darkest, most corrupt and repulsive side of his hometown. He would personally walk around town and collect tonnes of homegrown drugs, noting the corruption that had been eating away at the skin of this Donbas district centre. He saw through the façade, through all the layers of intrigue and cunning, their schemes and gangs. He knew what made each neighbour tick, what motivated every elected official, each visible player, not to mention those in the shadows of this city as well.

He had the incredible ability to call “a spade a spade”, “to tell it like it is”; no melodrama or sugar-coated words. What’s more, he possessed that quality rarely found these days: being able to reinforce words with deeds. He didn’t believe in good intentions; the road he followed was paved with actions.

When they say, “behind every act of kindness there’s a strong pair of fists”, that was Rybak to a T. No, he wasn’t a boxer, and he didn’t make a habit of waving his arms left and right. He was a fighter who availed himself of every possible means. And in his war he was victorious.

His struggle began well before 2014. He had already been elected deputy to the Horlivka City Council in November 2010. But he was a most impractical councillor.

“Rybak got under everyone’s skin” is something I heard not only from his wife, but also from many of his contemporaries. It was only after Rybak’s death that the local journalists made a film tribute to him, composed almost entirely of his sharp, sarcastic, scandalous speeches at city council sessions.

“Rybak got under everyone’s skin” is something I heard not only from his wife, but also from many of his contemporaries. It was only after Rybak’s death that the local journalists made a film tribute to him, composed almost entirely of his sharp, sarcastic, scandalous speeches at city council sessions.

He was that type of person for whom everything required action. You know, as we are sometimes asked, “Who are you that you need more than anyone else?” Yes, in fact, Volodymyr needed more.

He desired order. That the garbage be picked up not once a week, but twice a week. That the municipal government would actually get work done, and not just grandstand. That the homeless shelter help people, and not be used for money laundering. That the schools get renovated, and the daycares have properly sized windows.

He was often in court and always won. One particularly high-profile case was a right of action by the mayor who couldn’t handle criticism. He demanded ten thousand hryvnias in compensation for moral damages. Rybak mounted his own defence in court and won the lawsuit, arguing that politicians had the indisputable right to criticize other public figures.

His focus was always on human rights. His battle was the struggle for dignity, for the right to vote, and the possibility, be it only distant and theoretical, to live in a safe and respectable environment.

In no way is it possible that Rybak’s murder was a random act of violence. His family and friends categorically reject the plausibility of such an idea, namely, that he was a victim of circumstances or that he found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Volodymyr was an active participant in the Maidan and made several trips to Kyiv to join the protests. Every time he returned home, he held hundreds of meetings with local activists in order to inform them about the truth concerning the Revolution of Dignity, about all that he had witnessed and in which he himself had participated. All he needed was to see an injustice once, and it changed him from a local Don Quixote gentleman, idealistic and clueless, into someone to be reckoned with.

Of course, he wasn’t a major threat to the local elite, but he definitely was to those who represented the “Russian world” in the Donbas. He led the civic defence groups in Horlivka and in Donetsk. That winter and spring of 2014 was irreversibly transformed and demarcated by one obstacle after another. The phone calls were endless, and so were the negotiations. Dozens of meetings were held every day; hundreds and even thousands of kilometres driven along the local roads, all part of a titanic organizational work.

“Donbas has called on Putin for help” – This claim represents the most vindictive, the most cynical manipulation of the current war. Donbas did not call on Putin for help, but in fact fought against him with their very lives. To the absolute end, its residents supported the patriotic meetings, were vulnerable to bullets being fired, or rocks thrown, or exploding packages. The Donbas stood by itself to face down a maniac, one with unlimited resources and means to destroy the Donbas and all of Ukraine.

The moment came when the Donbas no longer felt that Ukraine had its back. That is, when individuals such as Rybak went into their final battle, fully aware that for them there would be no survival, or at best a slim chance that they would ever return alive.

This was a time when people clearly revealed themselves for who they truly were: the brutal were unconstrained in their inhumanity; the noble showed greatness of spirit and generosity.

For entire weeks and even months, there was a feeling that Horlivka was teetering on the edge of a chasm. With the strength of opposing forces nearly balanced, events could just as easily topple into the abyss as they could take a step back safely to civilian life within the jurisdiction of Ukraine.

Despite this nightmare reality, the war and the occupation surreally seemed like an incredible fantasy, like something no one would ever expect to experience personally in their lifetime.

We were under the impression that with just a little more energy, and a few more meetings, all would return to the way it once was. Pressure applied to the city council might finally spur it into action and begin to release beneficial decrees. If we could only get enough people to our public meetings to physically face down the agitators, who weren’t even residents of our city, because really, what are a few dozen provocateurs for a large industrial city?

By no means was there an equivalence in forces and counter forces, and it should not have been that one final factor that would tip the balance and become a serious and real threat to the government.

And in fact, the more one reads the chronology of events from that time, or watches available videos and listens to the accounts of eyewitnesses, the stronger the case might be made, irrational as the hope may have been, that it was possible for Rybak to emerge alive. However, history does not know the grammar of the conditional tense: but, what about, what if? If he had lived; what if they had held on just a little while longer; if only there had been reinforcements of just a small number from the rear; might Horlivka have avoided occupation?

And what if Rybak’s murder was meant to be a turning point, that rock which sets off an avalanche? Those who murdered him knew exactly what they were doing, targeting him, issuing a specific order to kill him, and abducting him in broad daylight. They targeted the heart of the defence; they broke the resistance.

The murder was exceedingly brutal for the purpose of sending a message. Undeniably sadistic. One man’s tragic death manipulated for a media circus.

Olena Rybak returns to one word over and over again during our conversation, a refrain which infuses her entire narrative: “Betrayal”.

She is convinced that her husband was betrayed. An incredible number of individuals are implicated in his death. Girkin (also known as Strelkov) and his henchmen were only the tip of the iceberg, directly carrying out the deed, but not the ones who ordered the murder.

She returns to the query, “For what purpose?” And she fails to find a convincing answer. And in this mute reply, in this desperate search, raking through every moment that preceded his death, she shares so much in common with a great number of other Ukrainian women who likewise have no idea, “Why him”? “Why did this happen to my family?”

The typical description of such losses and such trials include phrases that one’s world has fallen apart, and that they have left a hole in their chest. However, when you meet these spouses in person, are introduced to these daughters and mothers in the flesh, you quickly realize that the phrase is no mere metaphor. Where one’s heart once was, there is now a void, and nothing, not even the passing of time, can seal this void; there is no return and no revival.

There is one particular photograph in which Rybak’s wife and daughter are holding his jacket. They are clinging to it as to an anchor. The impulse is to glance at it and then to turn your gaze quickly away. You don’t want to look at it, don’t want to try it on, or even pull it to yourself to hug it, because the absence is impossible to comprehend, let alone a thing to grasp.

What does it mean to keep on living when that which had been the best part of your life is now completely in the past? This never-ending knot of pain, loss, guilt, sadness, obsessively analyzing what happened, and the non-stop list of questions. You mean he really couldn’t run away? You mean no one could rescue him? For what reason did my loved one die?!

In Rybak’s case, there was no running away. He was a fighter, and he purposely faced the risk, protecting and securing the safety of his family. He understood what dangers awaited his women, and he did everything possible to shield them from being implicated in anything associated with his community and political activity.

More than once he told his wife: “Don’t ask me too many questions because you’ll be in danger if you know too much. All in all, you’ll be better off not knowing what I’m involved in.”

He was well aware that “in the event of” something happening, he might not survive. He accepted such risk as part and parcel of his fate.

His murder became an irreparable loss for Ukraine. His death made us stronger, more hardened, and more cynical. Is it really that easy to kill a Ukrainian for the mere fact that he is Ukrainian? Can they get away with killing a Ukrainian on account of our blue and yellow flag, or our language, our national anthem, our country?

Yes. The answer is yes to all these questions. Such is the new reality into which we have been pushed, as into ice-cold water. The Rybak tragedy has become the stimulus needed to muster the strength required to emerge back onto the surface. His tragedy has forced us to thrash our hands and feet in anger and to fight for life.

And when we remember Volodymyr Rybak, let’s not call to mind the image of his lifeless, mutilated body, pulled from the river; or his stomach slashed open, the burns, the horrific wounds. And let us not think about the excruciating torture inflicted on him in the final hours of his life.

Let us remember instead the strong, handsome, resolute young man who mesmerizes us when we look at him. Let us think about genes that cannot be so easily obliterated with the stroke of a brush… and consider the courage he possessed that enabled him to laugh in the face of the enemy, that blood of bravery that is renewed and then renewed again in our land.

Let us consider the great honour and tremendous responsibility of being the son of one’s nation, and that while it is possible to destroy the body, the soul remains eternal.