A Russian lawyer who posed as a Stalinist and sought the rehabilitation of Stalin criminals, sometimes successfully and sometimes not, in order to conduct what he calls “a secret Nuremberg trial” against the Soviet system has brought his archive to the West.

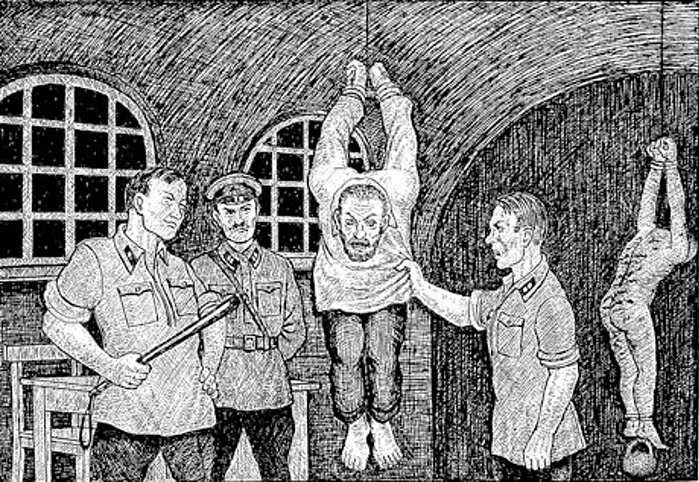

It shows that the Soviet secret police were every bit as much a criminal group as were Hitler’s Gestapo and SS and that there should but probably will never be a real Nuremberg trial in which those who participated in its activities and the system which supported them could be held accountable.

Aleksandr Busarov described his project, code-named “Nemesis,” to Radio Svoboda’s Dmitry Volchek (see svoboda.org and echo.msk.ru). It was brilliant in its cleverness and simplicity and was designed to force the Russian legal system to do the real work in exposing its Soviet predecessors.

Busarov’s plan, Volchek reports, was to have “the legal machinery of Putin’s Russia,” without understanding what it was doing, acknowledge the guilt of the Chekist system and bring sentences of a kind to those who were its participants by calling for the rehabilitation Stalinist criminals who had not yet received such vindication.

The Russian lawyer expected that the Russian military prosecutors would be forced to conclude that those who had not been rehabilitated really were criminals and therefore not qualify for rehabilitation and that the authorities would specify that even while dropping the original charges against them of being Trotskyites or other deviationists.

For this plan to work, Busarov had to pose as a committed Stalinist who wanted justice for other Stalinists so that they would view him not as some kind of democratic activist but as one of their own; and he had to make sure that nothing about his plans surfaced in the media which could have brought down the entire effort.

The lawyer began his effort in 2012 and sought the rehabilitation of senior secret police officials linked to Stalin and Beria. He chose a variety of people from a variety of periods so that his plan would not be apparent to anyone. And he was convinced that “the procuracy would take up the old criminal cases and confirm that the killers couldn’t be exonerated.”

But as he confirmed and as Volchek notes, things didn’t work out that way.

His appeals at first led the Russian military court system to rehabilitate many of these people, albeit in secrecy rather than in public, even though the individuals involved had been responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Soviet people. In the course of 2012-2013, Busarov was told that about 30 of those whose cases he raised had been rehabilitated.

It appears, the lawyer says, that after Putin’s re-election and the suppression of popular protests against election fraud, the military justice system felt free to take these steps, assuming that it had properly sensed the direction things were going in the Russian Federation of today. And so Busarov decided to exploit this.

Continuing to pose as a Stalinist, he was delighted by these rehabilitations and resolved to make sure that the entire country found out about what its rulers were doing. To that end, he began sending letters to various government offices demanding that the rehabilitated be given back the honors and awards they had received and then lost.

For better or worse, this one-man campaign was noticed, and other officials began to ask of the military prosecutors what did they think they were doing. That led to cases in which the system walked back the rehabilitations that the military justice system had issued in response to Busarov’s original efforts.

“This was a completely unprecedented case,” Busarov says. “There had never before been such a flood of de-rehabilitations in the history of the procuracy.” And it had consequences for those who had reached the decisions to grant these rehabilitations: they were in many cases punished in one way or another.

But not all those Chekists who were rehabilitated in 2012-2013 had their cases reversed, and Busarov began to send more demands for the rehabilitation of other Chekists. But now things began to work out differently. The prosecutors, perhaps warned about what such rehabilitations could lead to, refused to rehabilitate any of them.

What was striking, Busarov continues, is that no one asked what he was doing or why. The system treated his requests as entirely legitimate even though what he was doing was a kind of legal hooliganism designed to set the system against itself. And that prompted him to expand his program in two ways.

On the one hand, he began to seek justice not only for Chekists but also for their victims. And on the other, he began to demand the rehabilitation of those charged not by the Stalinist regime but by its Soviet successors. But in both cases, he was turned down: the victims, especially the more recent ones, weren’t going to get justice.

However, he did gain one important victory: the creation of a personal archive of the correspondence he had with official agencies, including sometimes secret materials that the Russian military prosecutors sent to him to explain what they were doing or not doing. However, the possession of such an archive became a problem.

Fearful that it would be confiscated and he would be arrested or worse, Busarov decided to come to the West and bring his archive with him and to share it with researchers in the West who want to understand how the Soviet system operated and how its post-Soviet successors are functioning as well.

His archive, Busarov says, shows that the Soviet security police were “a criminal organization exactly like the SS and Gestapo which were condemned at the Nuremberg tribunal.” And while no such trial has been held or is likely to be held for the Soviet criminals, his archive provides the legal basis for it.

He expresses the hope that “this archive will be of interest not only to historians but to legal specialists who could make the necessary conclusions and recognize the NKVD as the criminal organization it was.” Busarov doesn’t say but clearly intends that they will also draw conclusions about the nature of the Putin system as well.

Read More:

- Russian blogger Yakovlev: My grandfather was a “chekist” and a murderer

- Stalin’s NKVD and Hitler’s Gestapo cooperated closely even before Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

- Soviet chekists weren’t the professionals Putin wants Russians to think they were, new book says

- 134 bodies of NKVD victims unearthed in Ivano-Frankivsk

- Remains of executed victims found in Lviv’s Prison on Lontskoho Museum

- 107 remains of political prisoners executed by NKVD found in old Lutsk prison (photos)

- Lists of NKVD victims killed in mass executions in 1941 published online

- The forgotten tragedy of Koryukivka: How the Nazis exterminated a town of 7,000 souls

- Ukrainians discover stories of repressed relatives in newly opened KGB archives