Petro Poroshenko conceded his opponent's victory after the first exit polls were in on 21 April. The incumbent president didn't manage to bridge the gap with his opponent after the first round of elections on 31 March. Despite his convincing defeat, Poroshenko had a convinced supporter base: the following day after elections, April 22, a spontaneous "thank you" rally of several thousand voters showed up near the presidential administration. Its participants compelled Poroshenko to run for the presidency again, even "after one year" (to which Poroshenko answered: "if God wills") and thank him for such successes as the visa-free regime, Ukrainian church independence, development of Ukrainian culture, resisting the Russian aggression in the east, and reforms in Ukraine, which, in the words of Kurt Volker, special representative of the USA for Ukraine, exceed those of the last 20 years. Poroshenko's supporters online have now coalesced into a fan-club called "25%," which refers to Poroshenko's exit poll result.

A few thousand gathered near the presidential administration on Vulytsia Bankova in Kyiv to thank Petro @Poroshenko for his presidency. Photos: https://t.co/GEmisHPPa1 pic.twitter.com/BYEG30KsiT

— Euromaidan Press (@EuromaidanPress) 22 квітня 2019 р.

Nevertheless, most Ukrainians did not trust him to lead the country for a second term. Euromaidan Press has looked into the reasons why.

Read also: Why Zelenskyy won

1. Mistakes of the campaign

Poroshenko's campaign managers pointed out several mistakes of their tactics in an interview with Lb.ua. Yuliya Tymoshenko was determined as Poroshenko's main rival; Zelenskyy was not seen as a serious opponent.

The campaign wasn't duly prepared, audiences were not studied, and messages were not tested out, as it was assumed that there would be fewer demands to the incumbent president. The bet on large city mayors didn't pay off - their agitation failed to convert into votes.

The slogan "Army, language, faith," which refers to Poroshenko's policies of overhauling and strengthening the Ukrainian army, policies of supporting the Ukrainian language and domestic music and film production, and the campaign to attain independence from Russia for the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, worked only to mobilize Poroshenko's core voter base, possibly ensuring him the entrance into the second round of elections. But it did nothing to win over voters from Zelenskyy's electoral base - students from the Ukrainian south-east.

Before the second round of elections, Poroshenko's campaign made a bet on the fear factor by presenting Poroshenko as the only person capable of withstanding Putin. It didn't work.

"Poroshenko wanted Zelenskyy in the second round, being sure of his own victory. His campaign believed that people would vote for him out of fear, fear of the unknown and Zelenskyy's incompetence. But people were guided by other emotions and desires, which sociologists had highlighted. They were reared by information influences, the dangers of which Poroshenko always overlooked," wrote Ukrainian MP Mykola Kniazhytskyi.

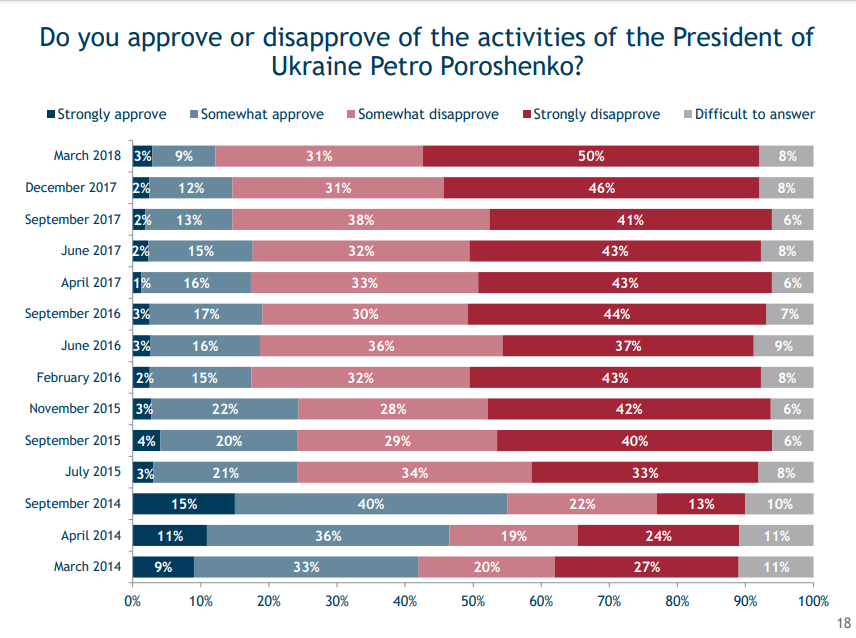

2. A high anti-rating

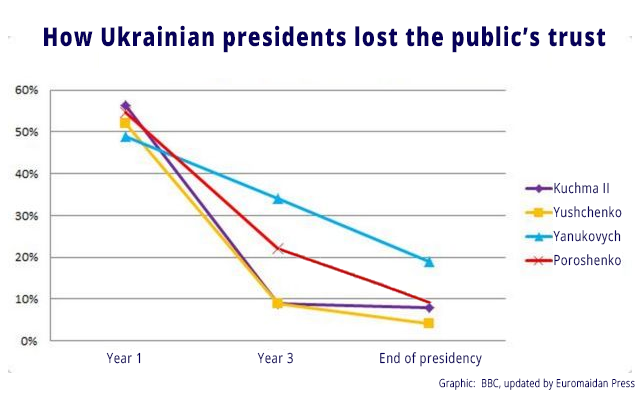

Poroshenko's approval rating dropped from the relatively high 55% after his election in May 2014 to roughly 9% at the end of his term.

In October 2018, 50.2% of voters said they would never vote for Petro Poroshenko, according to a joint poll by KMIS, the Razumkov Center, and the Rating group; only 6.5% stated they would vote for the incumbent president. This anti-rating grew to 58% in April 2019. Zelenskyy became the anti-Poroshenko, epitomized the protest vote.

Poroshenko's high anti-rating led to his defeat. It was a combination of many factors, which we have attempted to dissect below.

a) Ukrainians hate the authorities

Ukraine is a post-colonial country. Throughout the centuries of foreign rule over Ukraine, the authorities were hated figures who were to be despised, not cooperated with. At the same time, citizens' expectations of the authorities are paternalistic and infantile, which is a relict of Soviet times, when citizens were voiceless dependents of the authoritarian social state. The average Ukrainian voter views the president-elect as a Messianic figure with a magic wand who will put all the bad people in jail, raise salaries, and fix the potholes in the driveway.

The Ukrainian electoral cycle is a cycle of being disenchanted with the government. The Ukrainians' distrust towards the government has grown throughout all the presidencies. Only sometimes, before elections, people see a leader who is supposedly capable of governing the country, but immediately after, the curve of expectations falls, and the disenchantment skyrockets. These are some of the ideas of Ukrainian veteran sociologist Iryna Bekeshkina speaking at a seminar at the Institute of Philosophy on 23 April.

Poroshenko's drop in popularity is, therefore, nothing surprising - it is, rather, in line with Ukrainian tradition. Throughout the 27 years of the country's independence, only one of Ukraine's five presidents was elected to a second term - but this is because Leonid Kuchma's rival was Communist Party leader Petro Symonenko, which is probably why the former was deemed the lesser evil.

"None of the presidents, including Petro Poroshenko, managed to change the system in the country," Bekeshkina back in 2017 explained why none of the presidents managed to get back their initially high levels of trust. "This is a system of an oligarchic-monopolistic economy, where parties and factions in parliament serve as political 'organs' of economic-oligarchic groups who promote their interests.

The vote for Zelenskyy was motivated by protest, paternalism, and infantility, Bekeshkina told at the Institute of Philosophy. This is apparent because voters believe the president's powers include spheres which are actually outside of his scope but important for them, such as tariffs and pensions - and subsequently, expect him to solve their most pressing life issues. On the contrary, things which they think aren't important, such as state awards, are not believed to be in his powers. Voters are prone to acting like the majority, so if a clear leader materializes, his support grows exponentially thanks to a high degree of conformism. Voters tend to blame the "Chief," who is considered to be responsible for everything, and guilty of all their troubles.

Thus, the vote for Zelenskyy was conditioned by Ukrainians' immanent hatred toward "the authorities" and their collective "Chief." With such a high anti-rating, Poroshenko could only hope for a miracle - or for all the other candidates to be even more hopeless. And that they were - except for one.

Read also: Ukraine’s support for Zelenskyy tells about infantility of society – Iryna Bekeshkina

b) Problems with communication and personnel policy

Speaking at a closed meeting with MPs from his party, the BPP after the second round of the elections, Poroshenko admitted that he lost the campaign because of communication problems and bad appointments, a source told thebabel.com.ua. The source, a representative of the BPP, said that in the last two years, such meetings were rare and during them, Poroshenko usually spoke and everybody else listened.

But Poroshenko flagged communication and personnel policy as his weak spots already after the discouraging results of the first round, at a meeting with civic activists on 6 April which, in their words, should have happened a long time ago. Only after the first round of elections did he start admitting that he made mistakes. After the meeting, Andriy Hordeiev, the head of the Kherson Oblast Administration and a key suspect in the murder of corruption whistleblower Kateryna Handziuk, finally resigned, fulfilling a demand that the activists had been putting forward for months.

But Hordeiev wasn't the only dubious appointment of Poroshenko.

"The president is conservative when it comes to personnel policy. His personal trust, instead of the professionalism of the contender, is often the key factor in making an appointment. And if the trust isn't there, then the appointment isn't made," political analyst Taras Berezovets noted already in 2016.

This policy backfired on multiple occasions. The status of ex-President of Georgia Mikheil Saakashvili went from Poroshenko's good friend and Odesa Oblast governor to merciless critic of Poroshenko to deported stateless persona. The exposed graft on army procurements of Poroshenko's friend and business partner Oleh Hladkovskyi, who was appointed as deputy secretary of the National Security and Defense Council, drew accusations of corruption to Poroshenko himself. And although Hladkovskyi was eventually fired, this was a far cry from Poroshenko's promise to end corruption in the army.

As well, the appointment of his business partners Boris Lozhkin as head of the Presidential Administration, Valeriya Hontarieva as head of the National Bank, and positioning of Ihor Kononenko as the "gray cardinal" of Poroshenko's party stood in contrast with Poroshenko's 2014 pre-electoral promise of transparent appointments.

"Basically, it's logical. Poroshenko, being a businessman, had close and trusting relationships with his business partners. He decided to rely on them when he became president. But, unfortunately, he remained a businessman, being unable to use political will to remove those who had become toxic for him from his surroundings," is how journalist Mariya Pryzyhlei described the situation.

Thus, Poroshenko was unable to meet the post-Euromaidan expectation of renewing the political elites. Additionally, his unclear dealings with oligarchs Rinat Akhmetov and pro-Russian persona #1 Viktor Medvedchuk reinforced Poroshenko's standing as a person of the old system.

The meeting with activists on 6 April underlined the absence of real dialogue with civil society during Poroshenko's presidency. But dialogue was bad with Ukrainians overall: Poroshenko's associates created a warm bath for themselves and the president, branding any dissenting opinion as the voice of a "Kremlin agent" and ignoring real grievances of ordinary Ukrainians, who were shocked by skyrocketing tariffs and high prices and received no explanation, who were angry at the mistakes and bad appointments.

Nobody explained why everything was happening as it was, what was the reason, and how the situation could be fixed.

"First, we had a lot of screw-ups. They should have been addressed, screened, defused by something positive. But instead of that, things were done on the off-chance. Second, contemporary politics is built on trust. Poroshenko has no trust, and you can't build it up in a few weeks," Poroshenko's staff member told LB.ua after the first round of elections.

c) Unpopular reforms and failed reforms

Poroshenko had constantly been criticized as failing to do enough to reform Ukraine. And the successes that did take place happened despite the President, not thanks to him, went the popular legend, illustrated in an op-ed by Dariya Kaleniuk and Melinda Haring in the Washington Post.

This is a dubious thesis. It was Petro Poroshenko's party which had constantly supported important reform bills in the Verkhovna Rada, according to research by VoxUkraine. Without its votes and the votes of the "People's Front" party, adopting any kind of laws would have been impossible.

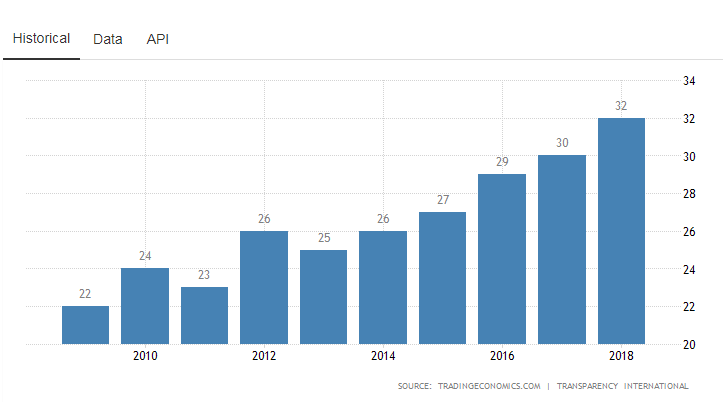

Most often, the president was lambasted for failing in the fight against corruption. Paradoxically, this fight became both Poroshenko's failure and success.

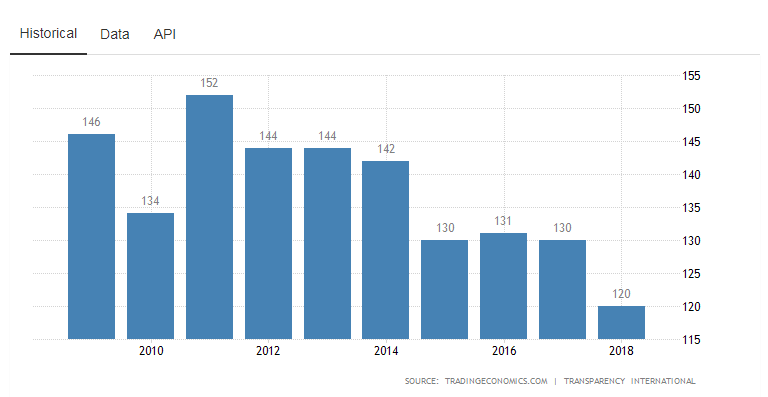

Thanks to transparency and deregulatory measures made between 2014-2018, Ukraine saved 6% of its GDP annually ($6bn), according to the Institute for Economic Research and Political Consulting. These included reducing Ukraine's tax corruption, cutting ineffective procurements, reforming the state monopolist Naftogaz, and increasing transparency. During Poroshenko's presidency, Ukraine's corruption perception index got better, and the corruption rank dropped.

So, objectively, Ukraine became less corrupt. And we can suppose that Poroshenko gained enemies among the elites who had their money flows cut off.

At the same time, increased transparency allowed the media to illuminate cases of corruption. Taken together with an unreformed court system and foot-dragging in creating the anti-corruption court, the exposed corrupts did not receive punishment, a sense of outrage and powerlessness was created among the population. Corruption was viewed as nearly as significant a problem as the war in Donbas, and ordinary citizens placed the blame for it on the president and government, while being reluctant to change their own habits and engage in fighting corruption at local levels themselves.

In fact, paradoxically, measures to stop corruption in customs made Poroshenko the enemy of a significant community of smugglers, who had made a living on violating the customs laws and contraband over the 25 years of Ukraine's independence. And this includes not only Ukraine's bordering regions but those profiting from corruption inside the country. Thus, the motivation for voting against Poroshenko in Ukraine's Zakarpattia Oblast on the border with Hungary included hopes for restoring the illegal smuggling channels of the region.

The failed judicial reform initiated by Poroshenko contributed to the "nothing is changing atmosphere," and Poroshenko's reluctance to admit the problems did not score him any additional points, as well as raised suspicions that he was in favor of preserving judges who would make political decisions on his behalf. However, attributing the failure to the president only is not fair: the corrupt courts did not appear yesterday - they are the result of a corrupt political system with many stakeholders.

The medical reforms of acting Health Minister Uliana Suprun deserve a separate notice. They affected the interests of mafia clans and disrupted existing procurement and money laundering schemes. In result, Suprun faced information attacks which, being exacerbated by the difficulties that come with money-saving and optimization measures, created a negative image of the reform. Before long, a myth of "genocide of Ukrainians" was created. Thus, a highly-needed reform resulted in the dissatisfaction of not only those who had the money flows cut off but ordinary Ukrainians who were impacted by the information attacks. And Poroshenko's rating took a blow.

d) War and poverty

Assuming his position in 2014, Poroshenko promised to end the war in Donbas not in a matter of months, but hours. In the summer of 2018, he apologized before Ukrainians for setting expectations too high.

Petro Poroshenko's opponents accuse him of being unable to end the war quickly. To this, he replies that the keys to ending the war are not in Ukraine but in Moscow.

Managing to freeze the conflict in Donbas after the adoption of the Minsk agreements, Ukraine set out on rebuilding its army, achieving impressive results compared to its state in February 2014, when only 5,000 combat-ready troops were available for both resisting the Russian occupation and responding to the build-up of Russian troops at Ukraine's eastern border.

Nevertheless, the war slowly drags on, taking lives of soldiers every day. A popular conspiracy theory is that the war continues as it's profitable for the Ukrainian establishment.

In the election campaign, Poroshenko argued that his opponent is not experienced enough to be a good commander-in-chief. "If you're such a good commander-in-chief, why do we still have a war?" Zelenskyy rebutted with his pre-prepared phrase during the show that replaced real debates at Olympiyskyi stadium in Kyiv.

The war precipitated another problem - poverty. In October 2018, Ukraine received the status of Europe's poorest country by GDP per capita. After Russia's occupation of Crimea and start of the war in Donbas in 2014, Ukraine, already being poor, underwent economic shock and a threefold depreciation of its currency, lost factories in occupied Donbas and economic ties with Russia, and increased spending on defense.

Taken together with rising tariffs and the pension age, a requirement of the IMF, this contributed to the growth of poverty - or at least, a feeling of poverty. Because in the years of Poroshenko's presidency, the economy managed to rebound. Although nominal wages have not yet matched pre-2014 levels, real wages (corrected for purchasing power) are higher than in all previous years of Ukraine's independence.

Nevertheless, many Ukrainians associate Poroshenko's presidency with their worsened living conditions. "Today one dollar is worth 27 hryvnias, and in Yanukovych's time, the exchange rate was 1:8," goes the popular accusation.

Low salaries and pensions contributed to the growth of economic migration; because of this, the visa-free regime Poroshenko touted as his victory became a symbol of seasonal agricultural labor in Poland, not a chance to drink coffee in Vienna as advertised by the president. The tariffs were especially painful: reducing them is the number one expectation of Ukrainians for the future president, despite the fact that regulating tariffs is outside his responsibility or scope.

Against this backdrop, the news of oligarch Poroshenko's income increasing nearly a hundredfold in 2018 compared to the previous year appeared to be no less than treason. His secret luxury vacation on the Maldives dug up by investigative journalists, which cost his family $500,000 for one week, fueled public hatred. The fact that Poroshenko had dropped out of Forbes' list of billionaires back in 2015 made no impact on the public perception of Poroshenko as "a president that profits at a time of war." Neither did his generous donations to Ukrainian charities, many of which he attempted to keep secret.

d) Unfulfilled promises

Poroshenko's wealth was all the more irritating because he continued being a businessman while serving as president.

"The expansion of the network of shops of the 'Roshen' [candy] corporation, which belongs to Poroshenko, became a symbol of the expansion his business empire. People see them at every step, this causes irritation. The acts of vandalism against these shops constitute the release of aggression connected to these moods," political scientist Volodymyr Fesenko told BBC.

Poroshenko promised to sell the corporation but instead handed it to a blind trust. However, Roshen isn't the only enterprise he owns. Poroshenko's business empire includes confectionary, agriculture, insurance, banking, shipping, defense industry, food manufacturing, and other ventures. As well, he owns a TV channel, "5 Kanal." One of his pre-election promises was to sell everything, except "5 Kanal." He never did, which led to obvious conflicts of interest during his term.

e) The media's skewed portrayal of reality

In 2018, the level of Ukrainians' distrust, frustration, despair, and disenchantment was at a record high since 1991.

But objectively, the index of social wellbeing of Ukrainians was also at a record high, Iryna Bekeshkina told at a seminar at the Institute of Philosophy in Kyiv on 23 April. This means that, objectively, Ukrainians feel better than during all the years since Ukraine's independence, but believe that times have never been worse.

According to Bekeshkina, this illustrates the high influence of media on the perceptions of citizens. It was the mediasphere that created this virtual reality, where the average Ukrainian believes that his wellbeing is terrible while objectively it's doing fine and even better.

Despite Poroshenko's obvious drawbacks and downfalls, Ukraine did make progress in his presidency. And there were unmistaken victories as well: the Tomos of independence from Moscow for the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, the visa-free regime, macroeconomic stabilization, an international support coalition against Russian aggression. However, even these victories were presented as defeats in the Ukrainian media. Here, Ukrainian media was an unwitting accomplice to Russian propaganda, which wasted no opportunity to denigrate Ukraine's authorities and convince that the country is in a state of ruin after the Euromaidan revolution.

Read also: How Zelenskyy “hacked” Ukraine’s elections | Op-ed

3. Seismic electoral changes

The story of Poroshenko's defeat would not be full without mentioning the seismic changes in the behavior of Ukrainian voters.

According to Ukrainian veteran sociologist Yevhen Holovakha, deputy director of the Institute of Sociology, the main conclusion of the presidential election is that voters chose incertitude and opted for new faces in politics.

"It's a choice between incertitude with a new face and definiteness with an old face. It's clear that the majority chooses incertitude - with the situation in the country, with their own fate. This is a very interesting phenomenon.

The post-Soviet elite created a society which doesn't work for the overwhelming majority of the country. And this is independent of whether the situation in the country gets better or worse. It improved in the last two years according to many indicators, including objective economic ones. [...]

All the post-Soviet elite is a combination of the Communist party-komsomol elite, first the red directors, then shadow players of the economy, civic actors who came to power through Parliament. They built a power system which is comfortable for them, where the tops live 'in Europe,' but the rest of the population...

This doesn't work for the majority. It looks for faces which aren't connected to the past. [...]

There is this understanding in society that elections are the most effective path. I believe that the Zelenskyy phenomenon is an 'electoral Maidan' of sorts. When the power is changed without knowing what you get. It's a form of mass protest, without which calculating how it all will end is impossible."

Read also:

- Ukraine votes in second round of presidential elections: live blog

- Putin’s plan for Ukraine

- Five years of Poroshenko’s presidency: main achievements and failures

- Sociology of Ukrainian elections: who votes for Zelenskyy/Poroshenko and why

- The difference between Zelenskyy and Poroshenko: piecing together the evidence

- Ukraine’s presidential campaign goes showbiz as Poroshenko attempts to rebound after first round

- Analysis: Among presidential candidates Poroshenko is the key target of hate speech on “Russian Facebook” VK

- Ukrainians once again are voting for someone they hope has a magic wand, Portnikov says