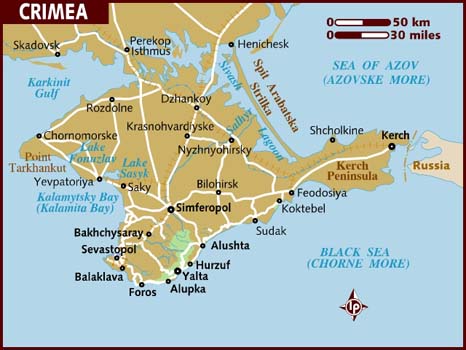

Moscow has made a concerted effort to present the Crimean Tatars as simply a branch of Tatars who happen to live on the Russian-occupied peninsula and thus do not have the legitimate right to a separate national self-determination, an approach that unfortunately is sometimes copied by international organizations.

Many Crimean Tatars are uncomfortable with “Crimean Tatar” as a designator because it implies links to other Tatars that do not exist and are pushing for the self-designator Krymtsi, a term stressing their ties to their land but that leads to confusion with the Krymchaks, another minority there which speaks a related language but professes Judaism not Islam.

All of this has given rise to debates among Crimean Tatars about what they want to be called and why (hromadske.radio) and to the appearance of an important book, Natalia Belitser’s Crimean Tatars as an Indigenous People (in Ukrainian, Kyiv, 2017).

Belitser, an expert at Kyiv’s Pylyp Orlyk Institute for Democracy, has now presented her arguments about the importance of the names given to the Crimean Tatars in detailed and heavily footnoted English-language article for the Washington, D.C.-based International Committee for Crimea (iccrimea.org).

The key passages of this article are as follows:

Crimean Tatars: who are they? Are they just a branch of the Tatar people, differing from the Kazan Tatars or Volga Tatars, only by virtue of the geographical location? Or, are they a separate nation with its own history, unique cultural, linguistic, and other characteristics? These questions are not just of interest for ethnologists, anthropologists or other academics; apart from addressing theoretical debates, the answers may impact perceptions and have possible legal ramifications for resolving a whole series of Crimean Tatar issues.

Until the tragic events of the 20th century, ethnonym ‘Tatars’ was the widely used designation for Muslim residents of Crimea as well as all other Muslim groups and peoples in the Russian Empire. It did not conflict with Crimean Tatar self-identity and was not objectionable to them. But after the en masse deportation of the indigenous Crimean population under false charges of collaboration with the Nazis, the Crimean Tatars were flatly denied any mention of their separate ethnicity and were identified in official documentation as simply ‘Tatars.’

To emphasize their distinctiveness from other ‘Tatars,’ Crimean Tatar intellectuals and politicians discussed for years the possible replacement of the ethnonym ‘Crimean Tatars’ with ‘Krymtsi (Kırımlılar in Crimean Tatar, which means Crimeans) and have also tried to revive and preserve their own language, cultural and religious traditions and social institutions.

Fundamental differences between various groups of Turkic-speaking peoples, often artificially unified under the common name ‘Tatars,’ are confirmed by the modern science of molecular biology and molecular genetics which use DNA-analysis to clarify the genetic origins and genetic relationships within and between groups.

Meanwhile, in English language literature the names ‘Tatars’ or ‘Tatars of Crimea’ are often used as synonyms for the ‘Crimean Tatars’, sometimes revealing a preference for the first option. Moreover, in some publications, a rather derogatory term ‘Tatars’ (from ancient Greek Tataros thus assuming them to be ‘Barbarians’) can also be found.

[Moreover,] the very term ‘indigenous people’ is usually avoided; the Crimean Tatars are designated instead as belonging to ‘vulnerable minorities’, or ‘national minorities’, or as a ‘Crimean Tatar community.’ Whereas for such categories, in contrast to indigenous peoples, any collective rights, first and foremost – the right for self-determination – are not foreseen in the international human rights and humanitarian law.

This trend continues up to the present: for example, in a recent publication on the 5th anniversary of the annexation of Crimea, the author, while adequately assessing the whole event, wrote that “Furthermore, Russia has launched a campaign of persecution and intimidation of the ethnic Tatar community there.” But if the Crimean Tatars continue to be regarded as belonging to an undifferentiated Tatar ethnos or as a subjugated ‘minority’ or just a ‘community’ but not an indigenous ‘people’, it follows that their claims for self-determination in their homeland Crimea can be neglected, especially given the existence of a national Republic of Tatarstan – a subject of the Russian Federation.

This interpretation has been applied by the occupational power in Crimea and the Russian central authorities. In order to prevent any possibility of providing ‘indigenous status’ for the Crimean Tatars, the Kremlin Presidential administration commissioned Sergej Sokolovskyj to undertake a special study to ‘prove’ that such a status is not justified not only by the national legislation but by the international law as well. [His report is discussed at khpg.org.]

In Ukraine, for a long time the efforts to ensure the rights of Crimean Tatars by providing them with the special status of ‘indigenous people’ remained, alas, unsuccessful. Legally they continued to be regarded as one of the numerous ‘national minorities’ based on the outdated law ‘On National Minorities of Ukraine’ (adopted in 1992, and still in force). Official recognition of the Crimean Tatars as indigenous people occurred only on March 20, 2014 – in other words, after the occupation and annexation of the Crimean peninsula by the Russian Federation.

Nevertheless, in publications and public discussions, the Crimean Tatars have usually been addressed as the ‘Crimean Tatar people’ thus granting them recognition by default as a nation and distinguishing them from other ‘minorities’ – including Armenians, Bulgarians, Germans and Greeks, namely, those ethnic groups formerly deported from Crimea.

There is a growing understanding of the major difference between ‘traditional’ national minorities having their own national states (‘kin-states’) beyond the borders of their country of residence and citizenship, and the Crimean Tatars with their history of former statehood (the Crimean Khanate) and the current situation of a ‘stateless nation’. Unlike national minorities enjoying various forms of the legitimate support provided by their ‘kin-states,’ the Crimean Tatars, being a numerical minority in any place of residence, have developed an acute sense of a constant threat of further assimilation and gradual ‘dissolution’ within the quite distinct, culturally and religiously, majority population.

Indeed, the unique Crimean Tatar cultural identity – in the widest sense of the phrase – can be preserved and further developed only through the concerted efforts of the people themselves and the Ukrainian state and society, with the active support of the international community.

Read More:

- Russia’s deportation of Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars from occupied Crimea a “neo-imperial policy tool” – report

- Russia may kill disabled Crimean Tatar with “most absurd” show trial yet

- Crimean Tatars see Budapest Memorandum as key to recovery of their homeland

- ‘The disappeared’ – the hidden part of Russia’s hybrid deportation of the Crimean Tatars

- Russian occupiers continue to destroy history and culture of Crimean Tatars

- Tatar political prisoner: I will continue to denounce Russia’s criminal government

- Putin repeating Stalin’s genocide with ‘new hybrid deportation of Crimean Tatars’

- The Crimean Tatar Palace and other historic sites Russia is destroying in occupied Crimea