After occupying Crimea, Moscow has been reshaping the ethnic composition of the local population, bringing in hundreds of thousands of people from across Russia. As of May 2018, according to official Russian statistics, some 247,000 Russians moved to Crimea since the annexation while about 140,000 people have left, mostly Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars. However, Ukrainian officials state that the real numbers are much greater, by hundreds of thousands.

Read also: Russians moving into occupied Crimea now form one-fifth of its population

Some of those who had to leave Crimea for mainland Ukraine were forcibly expelled by the decisions of occupation courts. The research "Forcible Expulsion of the Civilian Population from the Occupied Territory by Russia," a special issue of the thematic review of the human rights situation under occupation "Crimea beyond rules," mentions 2,425 identified cases of such expulsions. The authors of the report deem them a kind of "cleansing" for the continued colonization of Crimea by Russians, which in itself is a neo-imperial policy tool, as was stated at a PACE side event in June 2018, where the report was presented.

"The purpose of such a policy is to use in the future the thesis about the unwillingness of the 'people of Crimea' to return to the jurisdiction of Ukraine," the paper's authors note.

The paper was released by the three human rights NGOs - the Regional Centre for Human Rights, the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union, and an analytical group which wanted to remain anonymous - CHROT - in July 2018.

In February 2014, Russia started a military operation to occupy and annex a part Ukraine - the Crimean peninsula. Within weeks, Russian troops without insignia took control of the local official bodies, critical infrastructure including airports, and Ukrainian military facilities.

On 16 March 2014, a so-called "referendum" was conducted in Crimea to justify the further annexation of Ukrainian territory. This "referendum" was illegal under Ukrainian laws and its result hasn't been recognized by the international community ever since then. On 27 March 2014, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution

underscoring that the referendum had no validity and affirming the territorial integrity of Ukraine within its internationally recognized borders. Two years later, the UNGA recognized that the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol have been temporarily occupied by Russia.

Only two days after what Russia called a referendum, on 18 March 2014, Russian president Vladimir Putin signed the so-called "Treaty on Accession of the Republic of Crimea to the Russian Federation" with Sergey Aksyonov, Vladimir Konstantinov, and Alexey Chaly. Aksyonov was proclaimed the Crimean prime minister by the occupation forces when Russian troops seized and controlled the building of the Crimean parliament in Simferopol, and Chaly was a Russian citizen whom a crowd in Sevastopol pronounced a "people's mayor" of the city. Konstantinov was the only Ukrainian official to sign the unlawful treaty on the annexation - he was the head of the Crimean parliament at the moment of occupation just three weeks before signing the treaty with Putin.

Article 5 of the "Treaty on Accession" automatically recognized all Ukrainian citizens and stateless persons residing in Crimea as Russian nationals. The only way to avoid being forcibly naturalized was to inform the de-facto authorities of the intention to opt out of Russian citizenship by 18 April 2014.

For most Crimeans, it has been next to impossible to revoke Russian citizenship because they risked having problems with employment, medical treatment, registering children at schools and so on up to the forced deportation from their occupied homeland.

However, many Crimean residents refused to obtain Russian documents.

Aliens in their own land

Russian immigration laws allow foreign citizens or stateless persons to stay on the territory of the country for up to 90 days out of a period of 180 days.

On 15 June 2014, 90 days passed from the day the annexation treaty was signed, and the Crimeans who remained Ukrainian citizens but did not get a residence permit in the Russian Federation automatically became violators of Russian immigration law. Foreign citizens (except for citizens of the Russian Federation) and stateless persons who entered Crimea before 18 March 2014 or resided there faced the same fate.

The study "Forcible Expulsion of the Civilian Population from the Occupied Territory by Russia" notes: "Forcible expulsions of Ukrainian citizens who were in Crimea at the time of occupation began in July 2014."

Such forcible expulsions have been to be carried out contrary to the will of the persons being expelled, on the grounds of judicial decisions of the occupying courts.

Russia expelled 2,425 Crimeans

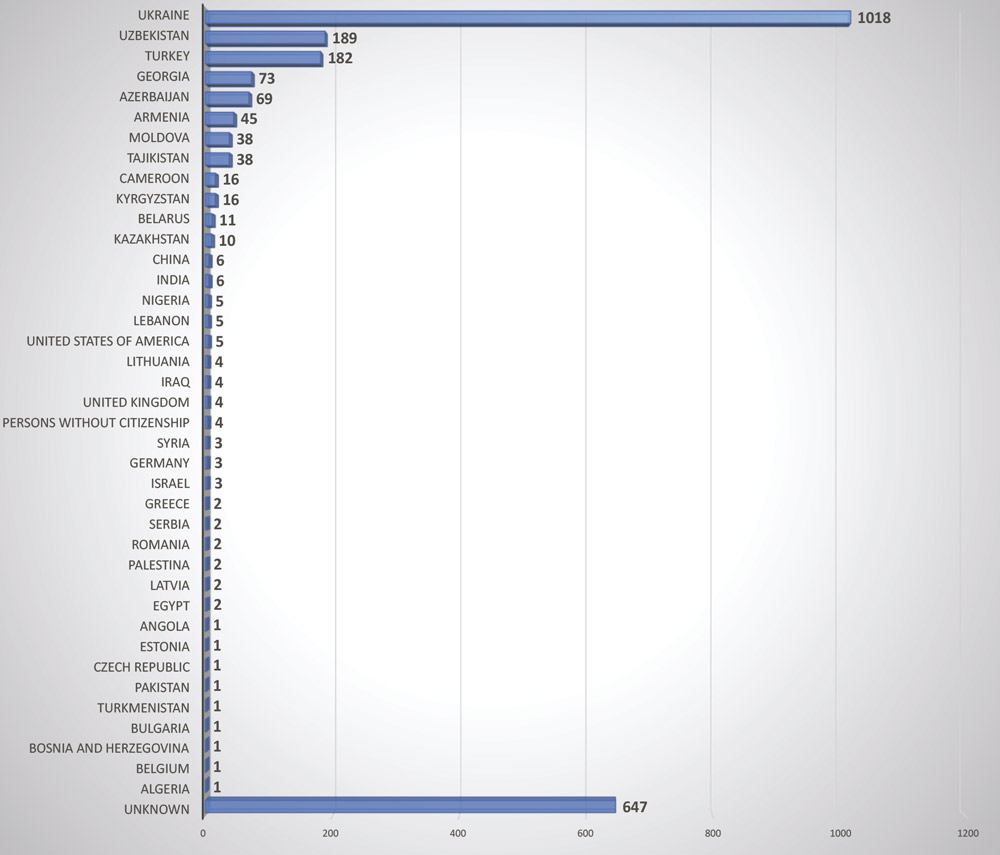

In total, the Russian courts in occupied Crimea tried 9,538 cases punishable by forcible expulsion. The study mentions that the researchers accessed data on 9,484 court decisions, of which 8,261 cases resulted in the imposition of administrative penalties. Among the data array, the researchers identified that courts imposed the penalty in the form of administrative expulsion on 2,425 persons.

Forced transfer to Russia before the expulsion

According to the paper, the Russian migration legislation was most harmful to Ukrainian nationals living in Crimea who refused to accept Russian citizenship. Other Ukrainians affected were those who lived in Crimea without official registration (Ukrainian citizens have the right to live anywhere in Ukraine without registration) and those who arrived after the occupation started.

Another category of those expelled by Russia from Crimea were foreigners with non-Russian citizenship.

Many people placed in such facilities awaited expulsion for several months or even more than a year.

"The Crimean Tatar Nedim Khalilov, who arrived to Crimea in 1986 from Uzbekistan, where his parents were deported in 1944 by the Stalin regime, and who lived there legally, was expelled from the territory of Crimea in November 2016 and placed in the specialized institution of temporary accommodation of foreign citizens in Vardane settlement of Krasnodar Territory. Later he was transferred to a specialized institution of temporary accommodation of foreign citizens Gulkevichsky, where he stayed until 15 May 2018, after which he was forcibly taken to Uzbekistan by plane. Until his deportation, Mr. Khalilov spent more than a year and a half at the specialized institution of temporary accommodation of foreign citizens under conditions of imprisonment," the study reads.

Months before his transfer from the Crimean territory, 57-year-old Uzbek citizen Khalilov was a Crimean Tatar activist who filed a lawsuit in one of Simferopol courts, asking to "recognize the actions of the occupying authorities, as well as the President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin, illegal, and to grant the Crimean Tatar people a special status and recognize them as the indigenous people of Crimea."

"Stalin gave the Tatars three hours to get ready, I will give you no time"

The case of Crimea-born 58-year-old Ukrainian citizen Konstantin Sizarev is a quite typical example of a forced expulsion.

After the annexation, Mr. Sizarev continued to live in his hometown of Yevpatoria without obtaining a Russian passport. In late 2016, the Yevpatoria City Court found him guilty of violating the Russian migration regime and sentenced him to a 2,000-ruble fine ($31) and expulsion. The judge rejected the arguments that Mr. Sizarev lived in Crime all his life, residing with his civil wife and sons, as did a further court of appeals.

Konstantin Sizarev refused to comply with the decision of the occupation court and didn't leave Crimea. A month later, on 20 January 2017, the Yevpatoria City Court sentenced Sizarev to a 3,000-ruble fine and "forced expulsion outside the Russian Federation."

Overnight into 21 January 2017 Sizarev was transported from Crimea to the Russian territory and placed in a detention center in Krasnodar Krai where he was imprisoned for 27 days until the Russian authorities expelled him to mainland Ukraine.

Now in exile in the South-Ukrainian city of Odesa, Sizarev won't be able to reunite with his family in Crimea for at least five years.

Nothing new

The use of deportations and colonization is nothing new for Russia. Since Russia's first annexation of Crimea in 1783, it has been methodically replacing the indigenous Crimean Tatar population with ethnic Russians. Following Stalin's deportation of Crimean Tatars after WWII, which killed 46.2% of their total population, their numbers in Crimea dropped to zero. The Crimean Tatars have been slowly returning from Central Asia to their ancestral homeland after Ukraine's independence in 1991, but Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014 has for many become a second deportation.

Read more: Deportation, genocide, and Russia’s war against Crimean Tatars

Read also:

- Russians moving into occupied Crimea now form one-fifth of its population

- Putin repeating Stalin’s genocide with ‘new hybrid deportation of Crimean Tatars’

- Ex-terrorist leader: “Referendum in Crimea was a farce”

- Only Crimean Tatars have right of self-determination in Crimea, Kasyanov says

- Chronology of the annexation of Crimea

- Hacked military docs reveal how the Russian 18th motorized brigade invaded Crimea

- 74 years on, Russian genocide of Crimean Tatars continues

- The attack on media freedom in Crimea threatens to stop coverage of rights abuses

- Crimean jailed for Ukrainian flag announces termless hunger strike

- The Crimean Tatar Palace and other historic sites Russia is destroying in occupied Crimea

- Military base instead of a resort: Crimea four years after the occupation

- Putin seized Crimea with regular army but outsourced action in Donbas

- Russia prepared to occupy Crimea back in 2010 and other things we learned from Yanukovych’s treason trial

- First int’l human rights mission since occupation reports on how Russia crushes opposition in Crimea