Filip Rudnik: In January, Ukraine began celebrating the centennial of its independence. Ceremonies commemorating the Battle of Kruty* and the announcement of state independence in 1918** were unexpectedly modest. What does this post-Maidan process of creating a “new Ukraine” look like?

(*As Bolshevik forces of about 4,000 men advanced toward Kyiv, a small Ukrainian unit of 400 soldiers of the Bakhmach garrison (about 300 of which were students) was hastily organized and sent to delay enemy troops at Kruty, a railroad station 130 km northeast of Kyiv. In a bitter battle, about half of the Ukrainian soldiers were killed, but their resistance delayed the Bolshevik capture of Kyiv and enabled the Ukrainian government to conclude the Peace Treaty of Brest-Litovsk-Ed)

(**On January 25, 1918, the Tsentralna Rada of Ukraine issued its Fourth Universal (dated January 22, 1918), breaking ties with Bolshevik Russia and proclaiming a sovereign Ukrainian state. Less than a month later, on February 9, 1918, the Red Army seized Kyiv-Ed)

-It’s very difficult to predict what will happen. I see different trends colliding, so it’s hard to say which will come out the winner. Modest celebrations of the centennial of Ukraine’s independence in 1918, or should I say their almost complete absence, point to certain problems that we have in understanding our history.

– The current post-communist elites don’t think of themselves as successors of the 1918 Ukrainian National Republic. I believe they’re closer to communist Ukraine, because it’s in this world that they and their ancestors grew up. Modern Ukraine emerged in 1991 as a result of a compromise and still remains a hybrid state, somewhere between the Petliura tradition and the communist heritage.

FR: What are the main reasons for political disputes in Ukraine?

– The post-communist policy was to continue the legacy of the past and to preserve as many soviet-inspired institutions and personnel as possible. It was a program initiated by post-communist turncoats and the entire team of the first President of Ukraine Leonid Kravchuk, and somewhat later the Party of Regions, which took over the soviet electorate. However, there was an independent and democratic narrative that wanted to see Ukraine as a Central European state, completely separated from the soviet tradition. The post-communist government took over certain elements of the national narrative, but the entire oligarchic-soviet, patrimonial system remained in place. Neither the Orange Revolution nor Euromaidan were able to change it. The way power is exercised has changed a bit, but the system remains the same.

FR: Is that also true at the ideological level?

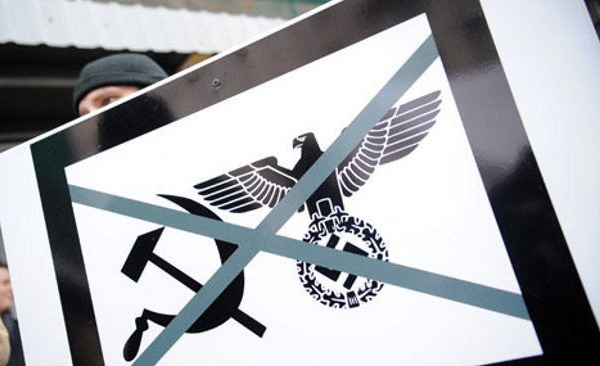

– This has changed as the largest Russian-speaking regions – part of the Donbas and Crimea – are occupied and don’t participate in Ukrainian politics. Moreover, the war with Russia has made it impossible to proclaim openly pro-Russian slogans. However, de-communization, declared in 2015, is conducted inconsistently and superficially. In no way does it mention restitution, although the essence of communism was based precisely on the confiscation of property and the liquidation of private property.

Jakub Bodziony: Poland is still dealing with privatization issues…

– I understand that it’s not easy, but it should at least have been declared. Instead, in Ukraine, the entire process of de-communization was reduced to symbolic prohibition of soviet slogans, monuments, names, etc. It’s foolish – firstly, because such restrictions aren’t inherent in a democracy, and secondly – because communism itself is dead and gone. It’s become totally marginal as an ideology and system, so we’re actually flogging a dead horse.

JB: Why has communism been “banned”?

– In my opinion, it’s replaced the de-colonization process. The authorities didn’t have the courage to say this frankly, because it would require major changes in public mentality. It’s easier to fight against something that no longer exists than with real problems. Many Ukrainians are still stuck in soviet space, that is, they’re victims of colonization. Many are under the influence of the Stockholm syndrome in relation to Russians, and so, a complex therapy is needed, and not just the demolition of past monuments.

JB: Why is there so little determination to act?

– After Euromaidan, our new government wanted to show the people that they were “new and different”. The easiest way to do this was to fight against the communist past because it was already dead and gone. It’s much harder to fight colonialism and its legacy because it’s so deeply ingrained in our society – including in the mentality of the ruling elite. It’s even more difficult to govern in a “new and different” way, eliminating corruption and destroying the old oligarchic system… although this would have brought about the best results. Poroshenko promised to do this, but he lacked courage… even though such a policy would’ve brought him a lot of popular support, as evidenced by public opinion polls.

JB: Do you also see this “colonization syndrome” manifested against Polish people in Ukraine?

– Yes, but to a lesser extent. There’s a certain sentiment passed down by the older generation. Young Ukrainians, whose ancestors lived in II Rzeczpospolita*, know that their grandparents were treated as second-class citizens. However, these groups aren’t as loud and influential as the Polish groups dedicated to destabilizing Ukraine-Polish relations.

(*The Second Polish Republic became a sovereign state under the Treaty of Versailles, June 1919. From 1918 to 1921, Poland solidified its independence in a series of border wars fought by the newly formed Polish Army. The eastern half of the interwar territory of Poland, including western Ukraine, was settled diplomatically in 1922 and internationally recognized by the League of Nations-Ed)

FR: What’s most important for ordinary Ukrainians?

– Surveys tell us that there are three important issues – the war with Russia, corruption and salaries and unemployment.

JB: Do you think these issues will dominate in the presidential and parliamentary elections next year?

– Yes, they will, but it’s very unlikely that President Poroshenko will be able to address them adequately. It’s much too late for real actions, in particular regarding the elimination of corruption, so now only traditional methods remain: mobilizing governors, manipulating the electorate and buying votes. Poroshenko had a great opportunity when he won the presidency under the slogan “Жити по-новому” (Living differently). But, he lost everything because he didn’t distance himself from corruption schemes and shady friends. He’s unlikely to win in a truly honest election.

FR: He seems to have no clear opponent, but according to some polls Yulia Tymoshenko seems to be leading…

– And this is a problem, because Poroshenko might create another strategy, representing himself as “the lesser of two evils”. However, this strategy may backfire if an appealing candidate suddenly comes out of nowhere – perhaps a Ukrainian-style Emmanuel Macron (current President of France-Ed).

JB: So, Ukraine is waiting for its own Macron? Are there certain conditions?

– I’d say it’s unlikely, but not impossible. The main obstacle here is that the most important media are controlled by the oligarchs. They can promote or compromise any candidate. Of course, there should be a certain consensus among the oligarchs with regard to a potential candidate, so that his election is successful.

FR: And who creates this consensus?

– The most important media belong to Viktor Pinchuk, Rinat Akhmetov and Ihor Kolomoisky. Poroshenko won the first round largely thanks to their support. He appeared to the majority of Ukrainian voters as what western political scientists call “the second best option”. It’s assumed that the first option is different for each voter. Therefore, it’s difficult for the electorate to agree with him because each voter has his/her “favourite”. But, “the second best” can be the same for all or at least for the majority.

JB: So, even back then, Poroshenko was the “lesser evil of two evils”?

– Exactly. After the Revolution of Dignity, there was a certain institutional vacuum that had to be filled. Moreover, due to Russian aggression in Eastern Ukraine, Ukraine simply couldn’t afford to stage a second round of elections, that is, to remain without a legitimate president and commander-in-chief for three more weeks. Today, the war is ongoing, but the situation is much more stable. Therefore, I don’t rule out the appearance of some Macron figure, perhaps Svyatoslav Vakarchuk (composer and frontman of the Ukrainian group Okean Elzy-Ed)?

FR: Are Yulia Tymoshenko* and Yuriy Boyko** really so discredited that they have no chance of winning the election?

(*Yulia Tymoshenko is the leader of Batkivshchyna, the second most powerful political party in Ukraine-Ed)

(**Yuriy Boyko is the leader of the Opposition Bloc party, composed largely of members of the ex-Party of Regions-Ed)

– Unless an unexpected candidate, a so-called “new face” appears that doesn’t get involved in election intrigue, the turnout will be low and anyone might win. Of course, Yuriy Boyko would be a more convenient opponent for Poroshenko because it would be easier to mobilize a loyal electorate by playing on anti-Russian sentiment.

It would be more difficult with Tymoshenko, but she can also be presented as a pro-Putin candidate. After all, she was skeptical of NATO at the beginning and refused to support Georgia during the Russian invasion. She was also seen chuckling when Vladimir Putin made snide jokes about Mikhail Saakashvili and President Viktor Yushchenko.

JB: Despite a deep political rift in Poland in the 1990s, the political parties worked together in order to join NATO and the European Union. Does Ukraine have a similar goal?

– There’s no such option in Ukraine. Membership in the EU and NATO is not a realistic prospect. Political consensus exists with regard to Ukraine not surrendering to Russia… even though Ukrainians are tired of this war. So, it’s quite possible that Tymoshenko will try to capture Boyko’s electorate and become more ambivalent about her former declaration on Ukraine’s pro-Western course. She might say, for example, that we should somehow come to an understanding with Russia – or even with the separatists – and agree to the concept of Ukraine as a neutral state.

FR: Will her voters go for that? A politician who’s been promoting a European Ukraine, and suddenly looking eastward?

– She has a good percentage of fanatically devoted voters who will accept anything. The problem is how to get more voters. Although she does have a higher level of support than the current president in different polls and surveys, her negative ratings are higher than everyone else’s.

JB: Why?

– Lack of trust. She’s all fake and hypocritical… and most voters see it and sense it.

JB: What about the support and backing of certain oligarchs?

– They’re true opportunists who’ll support anyone and everyone, that is, they’ll put their eggs in all the baskets. That’s why, despite all the changes in power, virtually no oligarchs have suffered significant losses.

FR: You said that Tymoshenko and Boyko could be discredited because of their pro-Russian ties or views. But the Roshen Confectionery Corporation, which is owned by Poroshenko, drew most of its profits from the Russian market.

– Poroshenko says that he’s closed Roshen in Russia and this argument will, of course, appear often during the campaign.

– Of course, he can be “burnt” by either Russia or the Western allies, especially the Americans, who probably have enough information to compromise everybody. But, this is an “atomic bomb” that they’re unlikely to use unless it’s extremely necessary.

FR: In October, MP Mustafa Nayem called for protests against the failure to create the Anti-Corruption Court. Will adoption of this law enable some parties to launch anti-corruption mechanisms in Ukraine?

– There’s very little chance of that happening. We see that the current government creates new institutions with old personnel. The Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office and the National Agency for Corruption Prevention haven’t lived up to people’s expectations. Our only hope is that the US will voice its support for a National Anti-Corruption Bureau.

FR: But, there’s a group of Poroshenko MPs that’s calling for the creation of an Anti-Corruption Court.

– Most deputies don’t want that to happen because they themselves are part of the system. They’re currently being pressured by the West, and the law went through a first reading and was sent for further processing, but the text wasn’t amended in accordance with the recommendations of the IMF, the Venice Commission and the EU. Will the politicians change it? Maybe, but only in order to get the next tranche of IMF loans.

– The Anti-Corruption Court is needed because, as experience shows, it’s impossible to destroy the entire corrupt system. Whatever evidence is collected by the National Anti-Corruption Bureau, our rotten courts destroy all cases connected to corrupt officials.

JB: In Poland, we, in a sense, think retrospectively about politics, examine our history, especially the national liberation fight, and always refer to the Polish People’s Republic. Even the current prime minister, a representative of the younger generation, is rooted in this discourse. What does it look like in Ukraine?

– History does not yet play a significant role. There’s nothing courageous about Ukraine’s current independence except for the 2014 Revolution of Dignity. There’s no reason for pride because all of today’s “elites’ co-operated with the communist system. None of them fought for Ukraine’s independence. In Poland, you have the “Solidarity” tradition; anyone can invoke it. But, our “elites” have nothing to be proud of.

FR: What about the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army-Ed)?

– Ukrainian politicians use the UPA and its symbols in a very opportunistic way… because of the war with Russia. Our volunteer battalions standing on the front lines can invoke UPA traditions. Ukrainian society doesn’t know much about its history, and politicians selectively pick up slogans that can be used.

FR: From the Polish perspective, the recent march in Lviv “Against all Polish masters” and the creation of “National Squadrons” in Ukraine raises fear and awakens strong emotions.

– These are marginal events, especially the so-called “march”. What’s worse is that we don’t know to what extent Ukrainian authorities, who are generally impotent, will go to tolerate nationalist “titushky” (thugs-Ed) and to what extent they actually encourage them.

– This may reflect the struggle of the presidential camp with people who support Arsen Avakov, Head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. According to my hypothesis, he has a certain interest in all these events. His deputies have a large faction in the Verkhovna Rada, but their current electoral support fluctuates within limits of statistical error. This party won’t win seats in the new parliament, so Avakov must have another card up his sleeve.

– Secondly, we don’t know to what extent all these provocations are inspired by Russia. For example, there’s fairly convincing evidence pointing to the involvement of Russian special services in two consecutive assaults on the Hungarian Office in Transcarpathia… and in both cases it was made to look like something perpetrated by Ukrainian “nationalists”.

FR: Don’t you think that flirting with nationalists can be dangerous for the state?

– Absolutely. Even if the state doesn’t take part, it may become a victim because it shows their weakness… and even more so, if the authorities sponsor them.

JB: What can you tell us about Volodymyr Viatrovych, Director of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, who is known for his controversial statements in Poland? Does he have a real impact on the situation in the country?

– Part of Ukrainian society mocks and criticizes him; these are people that criticize and oppose de-communization, almost half of Ukraine’s population. They look at Bandera in the same way. Both Viatrovych and Bandera are overly demonized in Poland. After all, Bandera was in a German concentration camp during the Volyn massacres, while Viatrovych is quite a moderate politician.

FR: Politician?

– Meaning that he follows a certain political line. He does have some preconceived ideas and presents a rather specific vision of history, incorporating the Volyn massacres into the larger picture of the Polish-Ukrainian war. He refers to a wider context, which is often ignored by the Polish side, and in this sense, his interpretation has the right to exist… I have nothing against it. In any case, he’s not a hard-core nationalist, of whom, unfortunately, there are way too many, both in Poland and in Ukraine. These people don’t know how to communicate, perceive other arguments. Viatrovych knows how to listen, analyze and answer logically.

JB: Is he supported by some powerful group or is he a “loose cannon”?

– Hard to say. We have an old tradition – from Kravchuk’s time – post-communists (and now oligarchs) flirting with nationally oriented persons: you want the tryzub and the blue and yellow flag – well, you can have them! You want Bandera – well, take him! But, just leave us alone and let us conduct our corrupt business affairs as before. In other words, leave the money to us and you get all the ideology. We get the gas and oil; you get the educational and cultural sphere.

FR: Maybe this national narrative has become so popular because there’s no competition?

– To some extent, yes. There are no contradictory myths, and all governments need some kind of ideology, especially in war conditions. I don’t think Poroshenko ever had clear ideological opinions, so he just grabs at what happens on the surface, according to the situation at hand… although there’s more to choose from.

FR: For example?

– Like the resistance of Ukrainian dissidents in the 1960-70s. Like the heroic and uncompromising figure of Vasyl Stus, who died in a Soviet concentration camp in the fall of 1985.

JB: What are the consequences of recent government actions – the law on the reintegration of Donbas, de-communization, anti-Russian rhetoric? Will they benefit Ukraine in the face of Russian aggression?

– There’s a lot of ambivalence here. After four years of war and thousands of dead and wounded, the authorities have yet to break off relations with Russia. Trade and commerce flourish; trains travel to Moscow as before, and even Russian consulates planned to open polling stations in their offices.

– However, I don’t see a bright future for Ukrainian-Russian relations. The Russian mentality refuses to admit the existence of an independent Ukraine. This issue isn’t just part of the Kremlin’s policies, but a question of Russian identity, which has been specifically shaped over the last hundred years. In order to allow an independent Ukraine to exist, a new revolution should take place in Russia.

FR: Who could instigate this revolution?

– There must be some kind of shock – defeat in the war or, let’s say, Kyiv’s admission to NATO.

JB: But, Russia hasn’t lost the war, and Ukraine won’t join NATO…

– Therefore, Moscow will continue to believe and proclaim that Ukrainians are Russians, and that, with the support of the Americans and Poles, Kyiv has been taken over by nationalists who are slowly pushing the entire country to the brink. Moreover, Ukrainian people are generally with us, Russians say; they don’t want this “Kyiv junta” and are waiting for us to liberate them! That’s the general conviction in Russia.

FR: So, if Ukraine succeeds and escapes from Russia’s influence, would there be profound changes in Russia?

– Only an effective and prosperous Ukraine can force Russia to reconsider its perception of the world and of itself. As long as Ukraine remains stuck between the East and the West, Russians will think that things can be turned around and their losses can be retrieved.