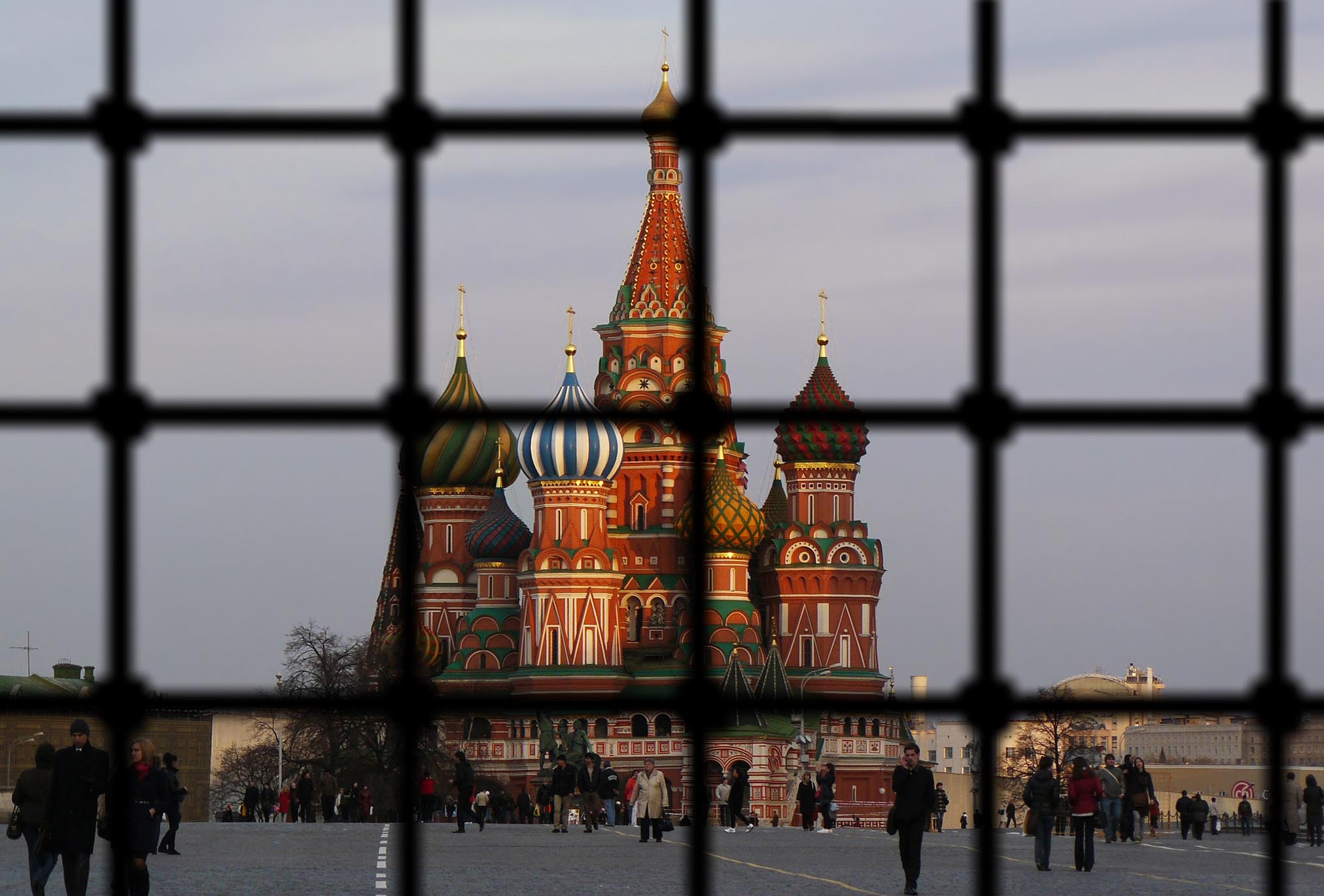

Vladimir Putin’s power is “not legal because he was not once chosen in correspondence with the law,” but it is “legitimate” because “the majority” of those people under his control recognize it as such since they know that they have little chance to change it, Igor Yakovenko says.

Like criminal groups who took over portions of Russia at various points in the last two decades, Putin “came to power over the corpses of blown up apartment blocks, the deaths of hostages at Beslan,” and then” as his power grew, via the oppression of “tens and hundreds of thousands in Ukraine and Syria.”

The legitimacy Putin now enjoys has “nothing in common with the classical types of legitimacy described by Max Weber,” the Russian commentator says. It is not of the traditional kind because Putin is too cowardly to restore the tsarist system. It is not charismatic because only the most naïve could see him as an outstanding personality.

And it is not legitimacy conferred by democratic, legal or rational arrangements. Indeed, Yakovenko argues,

“The basic source of Putin’s legitimacy and that of his power is total state force and total state lies.” The forms of the former are varied and selective, and he forms of the latter are “unprecedented in history.” Together, they give Putin the kind of legitimacy that the Stockholm syndrome gives a hostage taker among his hostages.

According to Yakovenko, “this type of legitimacy in Russian history has predominated more than two hundred years,” and its current hyperbolic form has an important consequence: “Power is becoming in principle alien,” just as that of criminal bosses are alien to the smaller groups of people they oppress.

Under Yeltsin but not under Putin, Russia could justifiably be called “a federation.” And for a time, it almost ceased to be an empire.” But that time has passed. Putin because of his cowardliness and weakness cannot bear anyone in the country to have “the slightest signs of their own legitimacy.” He alone must have that quality, however it has been achieved.

Such an arrangement is inherently unstable, Yakovenko says, but it is a mistake to predict where and when everything will come apart. It could start in the North Caucasus and especially in Daghestan or it could come from “any region” such as Siberia, the Urals, or even Moscow and St. Petersburg” whose interests Putin has denigrated just as much.

But one thing is clear, the commentator says, and it is this:

The reason for that is that “with each year the Putin regime lasts, the degradation of legal institutions and the alienation of people from the power grows; and this means that the base of the post-Putin independent states could become precisely regional [criminal groups]” who will maintain themselves by force and lies and by displaying hatred to the idea of Russia as a whole.

Related:

- Exiled Putin critic’s murder in Kyiv work of FSB, Ukraine’s top prosecutor says

- Six powerful quotes from Anna Politkovskaya about Vladimir Putin

- Russian-speaking Belarusians and Ukrainians threaten Putin’s ‘Russian world’ and Russia itself

- Putin era is coming to an end and both he and other Russians recognize that, Moscow sociologist says

- Russians mark Putin’s 18th year in power by reprising Brezhnev-style anecdotes

- Yakovenko: Putinist fascism – not an ideology but a set of criminal ‘understandings’

- How the Kremlin influences the West using Russian criminal groups in Europe