On 14 August 2017, the New York Times published an article by Pulitzer winning journalists William Broad and David E. Sanger stating that North Korea's recent ballistic missile success is explained by black market purchases of rocket engines "probably from a Ukrainian factory," namely - the Yuzhnoye construction bureau in its Russian transcription, or Yuzhmash, now known as Pivdenne, located in Dnipro.

North Korea's 4 July 2017 launch of the HWASONG-14 rocket with a range over 5,500 km had beemphawildered specialists. While the rogue country was in the possession of a nuclear bomb starting from 2006, the short- and medium-range rockets it managed to develop were ablemiti to carry it to South Korea, Japan, and US bases in Guam. Its attempts to create an intercontinental ballistic rocket capable of striking the USA were all unsuccessful. That is, until 2017.

The New York Times article was based on a report written by Michael Elleman, a Senior Fellow for Missile Defence at the British-based International Institute for Strategic Studies, and who led a Threat Reduction program in Russia from 1995-2001, and immediately made headlines around the world. After all, a US strategic ally had allegedly helped the US' mortal enemy. Predictably, Yuzhmash and Security Council Chief Oleksandr Turchynov denied Ukraine was involved. Meanwhile, Ukrainian President Poroshenko has ordered a probe into the allegations of the report.

But despite its popularity and well-known authors, the article appears to be, in the best case, extremely sloppy journalism, and in the worst - a hit piece with possibly grave consequences, according to Ukrainian officials and experts. Here is why.

What do the article and report claim?

In the report, Elleman states that North Korea could not have designed the new ballistic rocket. Previously, the country had used technologies from Russia's Isayev and Makeyev enterprises, but the parameters of the rocket in the recent July launch matched those of rockets produced in the Russian enterprise Energomash (also known as enterprise named after Glushko), and only the RD-250 family of rockets matched the external features.

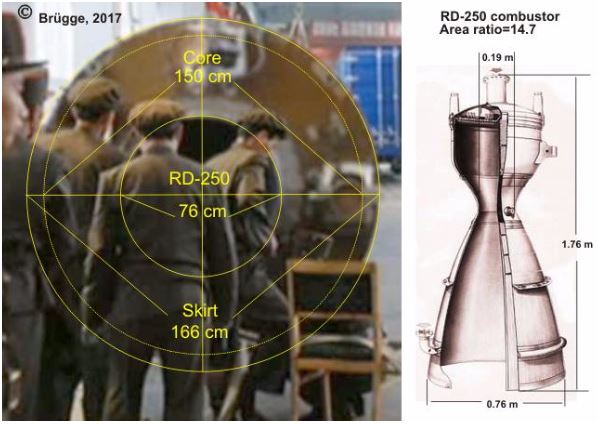

The NYT article also reported the findings of Norbert Brügge. a German analyst who analyzed a North Korea propaganda video featuring the missile and noted it is increasingly likely that it is similar to the RD-250, which for some reason NYT labeled as "Yuzhmash engines," despite them being designed in Russia.

The NYT times article claimed that Yuzhmash "remained one of Russia's primary producers of missiles even after Ukraine gained independence." This is false. After Ukraine's independence, Yuzhmash stopped producing military missiles altogether and moreover did not produce either missiles or any of their elements for Russia or for any other country, including rocket engines.

"Moscow had never applied to the Yuzhnoye construction bureau to create new modifications of the SS-18 rocket. Even if this happened, Ukraine would never have been able to do this, in accordance with its international obligations," a statement on Yuzhnoye's website reads.

Elleman says in the report that there are "almost certainly hundreds, if not more" spare RD-250s at Yuzhmash and warehouses in Russia, and that "a team of disgruntled employees could be enticed to steal a few dozen engines"() by illicit arms dealers operating in the former Soviet Union, all without proof. "The engines (less than two meters tall and one meter wide) can be flown or, more likely, transported by train through Russia to North Korea," Elleman adds.

8 times he connects Russia and/or Ukraine with the engines in North Korea, 6 of those times Russia and Ukraine are equally possible options for the source of the rocket; 1 time he names only Russia and 1 time - only Ukraine.

The NYT is less ambivalent: Yuzmash is stated as the unambiguous source 7 times, while the Russian option is named only once.

The reason? Ukrainian missiles experts were out of work because of the factory's difficult economic situation.

In his comments to NYT, Elleman points fingers directly at Yuzhmash, saying “it’s likely that these engines came from Ukraine — probably illicitly,” and: “the big question is how many they have and whether the Ukrainians are helping them now. I’m very worried.”

In later tweets, Elleman softened his claim, stating that he does not allege the Ukrainian government is involved (original tweets later deleted):

Elleman notes that while the RD-250 consists of a pair of combustion chambers, but that a single-chamber engine was used in Korea. He concludes that the Koreans couldn't have modified the engines on their own and that the modified engines a were made either in Yuzhmash or Energomash, where the expertise is. "Western experts who visited KB Yuzhnoye Ukraine within the past year told the author that a single-chamber version was on display at a nearby university and that a local engineer boasted about producing it," he continues. In an interview with The Telegraph, he declined to name the person who saw the engine. The NYT makes no note of this one-chamber detail.

- that the engine in the North Korean rocket is an RD-250, despite having one combustion chamber;

- that this type of single chamber RD-250 could be engineered and/or was available in Yuzhmash;

- that the several dozen spare RD-250s were simply lying around in Dnipro, could have been stolen by Yuzhmash employees, sold to the black market, and transported many thousands of kilometers to North Korea.

The assumptions of the article are shaky

Some questions about these assumptions:

- "Why Ukraine?" Russia is the country that maintains friendly relations with and shares a border with North Korea. RD-250s, if we do assume that they were in the North Korean rocket, are a product of a Russian design and are located at "Energomash’s many facilities spread across Russia," if we are to believe the report. North Korea's ballistic missile program to date had been grounded on Russian technology. Nevertheless, both Elleman and NYT state it was "probably Ukraine."

- Secondly, one would be hard pressed to imagine how exactly several dozens of engines, which are several meters long and have a dry weight of 788 kg, need to be packaged properly and are fragile in transportation, could be taken from a regime enterprise through 200 km to the Russian puppet statelets in Donbas, then through many thousands of kilometers of Russian-controlled territory without a single trace, person, transaction, photograph, bank check. Did North Korean spies break into the enterprise and smuggle the engines under their clothes? Elleman cites the only known incident of North Korean agents operating in Ukraine. In 2011, they were arrested and convicted to 8 years in prison for photographing dissertations and research articles related to missile technology in a garage in Dnipro. This is however, a far cry from transporting several dozen engines across a continent, unnoticed.

- Third, there is an intrinsic contradiction between 2) and 3): the engines could be either re-engineered by Yuzhmash OR secretly stolen by employees, not both. Elleman himself notes that redesigning an engine from a two-chamber version to a one-chamber version is no easy feat and could be done only in Yuzhmash or Energomash. So, either the redesigning was a planned act at the enterprises, or disgruntled employees stole old models from warehouses. You can't have both.

These assumptions are born out of the reasoning of Michael Elleman, determined by examining similarities in photos, that there is a possibility that the proposed model of engines could have come to North Korea from Ukraine or Russia. However, what's missing is the factual evidence.

Read more: Problems with the NYT article on Ukrainian rocket engines in North Korea

Euromaidan Press talked to Ukrainian experts in the field to find out how realistic Elleman's scenario is.

What is the RD-250 engine, anyway?

At a press conference organized by the State Space Agency of Ukraine (SSAU), the Ukrainian National Strategic Studies Institute director Volodymyr Horbulin, once an employee of Yuzhmash and former head of the SSAU, told about the history of the RD-250.

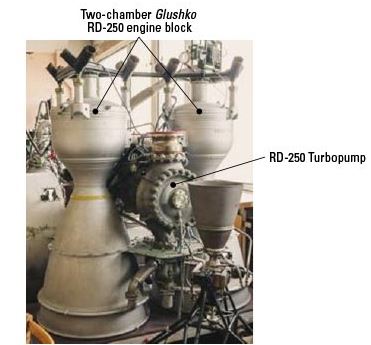

In 1962, the RD-250 was developed by the Glushkov construction bureau Energomash near Moscow as the engine for the R-36 rocket. At the moment, it was the most powerful Soviet rocket and played an important role in the arms race, allowing to develop a Soviet orbital combat unit which endangered the whole anti-aircraft defense of the USA. This rocket played an important role in the arms race. Its first stage contained three RD-250 engines, another one was on the second stage. The RD-250 is a liquid fuel engine has two chambers and one turbopump. The production of RD-250s for military missiles stopped in 1968.

The R-36 had a short life, but it became the great-grandmother of the powerful rocket called Satan, or SS-18, which is still in the armament of the Russian army. The Yuzhnoye construction bureau, Yuzhmash, and Pavlograd mechanical factory were all involved in manufacturing the SS-18. These rockets were destroyed in the early 1990s. The nuclear warheads were sent to Russia, and the rocket bodies were destroyed. The engines were converted and could be used in civilian launches.

Military rockets were later redesigned into space carrier rockets. On the basis of two R-36 rockets, two types of carrier rockets were developed: the Tsyklon 2 and Tsyklon 3. The Tsyklon 3 and Tsyklon 4, a later version, showed themselves as some of the most reliable carrier rockets in the world.

In Soviet times, the RG-250 was produced in Yuzhmash based on the design developed by the Russian Energomash up to 2001, Yuriy Radchenko, acting head of the SSAU, told. They were actively used to produce the Tsyklon-2 and Tsyklon-3 space rockets in the interests of the Russian Federation but were supplied only as part of the rockets. The engines were never produced as separate pieces.

Altogether, 111 Tsyklon-3 and 122 Tsyklon-2 rockets were produced. All the launches were successful.

Can Ukraine produce the RD-250 now?

Ukrainian enterprises have no ability to produce and supply the RD-250 engines, Radchenko said at the press conference. Furthermore, a part of its missile production capacities was destroyed after 1991. We checked this claim with Ukrainian rocket experts.

"Everything which was dangerous for the USA at Yuzhmash was destroyed under the agreement for disarmament. This was a condition for Ukraine signing the Budapest Memorandum," Yuriy Mitikov, Head of the Department of Engine Building of the Physical-Technological faculty of the Dnipro State University, told EP.

After 1991, Ukraine did not produce military rockets or any of their components. It underwent a process of disarmament. Starting from 1991, the technological lines for producing engines with characteristics analogous to the RD-250 were partially disassembled. The assembly line for creating SS-18 and engines for it were fully destroyed, the Yuzhnoye construction bureau wrote.

Although the RD-250s were produced up till 2001 to be assembled as part of the Tsyklon 3 and 4, it makes no sense to renew its production now, Vasyl Chabanov, deputy director at the Dnipro-situated Ukrainian Research Institute of Machine-Building Technology, who had worked on converting Ukraine's ballistic missile technology to meet space exploration needs, told EP: "This is the past century, there is no need to return to its production." Chabanov said that Ukraine potentially could resume production of the RD-250, but it would take several years to renew the technological process.

It's absolutely impossible that Ukraine could have produced the RD-250 for North Korea, Mitikov told EP. Yuzhmash had shrunk from 60,000 employees to 5-6,000, and they work 1-2 days a week. Although the enterprise has recently been engaged in new space projects, it would be hard-pressed to produce an engine of the class of the RD-250. The VG143 engine Yuzhmash is producing for the Vega EU rocket carrier is much less powerful, as it is for the fourth stage of the rocket. And Yuzhmash could not meet a recent proposal to produce first-stage engines for a carrier rocket.

"Two years ago, an American delegation came to Yuzhmash, proposing to develop the engine for Atlas V [a two-stage carrier rocket]. It puts military satellites into orbit. This would have been a terrific project for Yuzhmash, but unfortunately, the factory was hard-pressed to organize the technology and personnel, and they couldn't name either the terms or price. Two months ago, the US Senate allowed to lift anti-Russian sanctions to purchase the Russian RD-180 of this capacity, and the USA are actively working on developing their own engine of this class," Mitikov said.

Andrew Titarenko, former Acting head of the SSAU, told EP that it’s not in North Korea’s interests to merely buy engines.

“North Korea can hardly be interested in buying engines from elsewhere. It needs its own engine production to have its ballistic missile program running. In order to set up such a program, it needs a technology transfer from the engine manufacturer, or better from its designer. The RD-250 was designed by Russian Energomash, and only manufactured by Yuzhnoye.”

Thus, we can be confident that Ukraine could not have produced a new RD-250 for North Korea.

Maybe the engine in the North Korean rocket was an old RD-250 stolen from storage at Yuzhmash?

"The total number of RD-250 engines fabricated in Russia and Ukraine is not known. However, there are almost certainly hundreds, if not more, of spares stored at KB Yuzhnoye’s facilities and at warehouses in Russia where the Tsiklon-2 was used," Elleman wrote. Ukrainian experts disagree.

Mykhailo Samus, deputy director at the Ukrainian Center for Army, Conversion, and Disarmament Studies, told EP that he is "100% sure" that the USA Administration knows about each RD-250 engine in Ukraine, as when Ukraine started fulfilling the demands of the non-proliferation regime, this process was supervised by international commissions under the auspices of the USA, as part of the nuclear disarmament process.

"The USA experts have a full list of where these engines are located," Samus told.

RD-250s are indeed present in Ukraine, Yuriy Radchenko told the outlet AIN.UA. Three rocket carriers of the Tsyklon family are stored at Yuzhmash, meaning they contain 12 RD-250 engines - a far cry from the "several dozen" Elleman says are needed for North Korea's ballistic missile program. Their preservation is controlled by Ukraine's Security Service. According to the SSAU expert assessment, from 7 to 20 Tsyklon rockets are stored in Russia, meaning that 28-80 RD-250 engines are in the possession of Russia, as well as the documentation and expertise, Radchenko said.

If these engines got into North Korea, they would require the technology of producing rocket fuel (Nitrogen tetroxide/dimethylhydrazine). According to Radchenko, Russia and China have the technology to produce such fuel. However, Ukraine does not. The territory of Yuzhmash is under strict military control, as Ukraine is a participant in the International Missile Technology Control Regime; Ukrainian authorities are fully in control of the space-rocket complex of Ukraine, Yuzhnoye construction bureau stated.

Could there be separate spare engines stored at Yuzhmash which were, as Elleman supposes, stolen and sold to the black market?

The Yuzhnoye construction bureau stated that all the engines capable of flight, including the RD-250, left the territory of Yuzhmash only assembled as part of a rocket. The only engine which Yuzhmash supplied as a separate component, is the VG143 for the European Vega carrier rocket.

"A rocket engine isn't a box of matches or a nail, you can't just sell it to the black market. One RD-250 costs approximately $500,000. It's not just sitting around in a warehouse. Engines are not made on an assembly line, each one was produced separately, and each one was planned to be used in a specific piece of equipment. If there were some old engines left in Soviet times, they were all delivered to the Main Directorate of Missile forces and artillery of the Soviet Union. Why? Because in Soviet times, everything produced was delivered, the plan was met, and based on that the salaries were paid. There couldn't have been engines left at all. They went to the arsenals in Russia and maybe they were launched. Maybe, some engines are still in the arsenals in Russia," Mitikov told EP. "For instance, a series of engines for 5 rockets is ordered. You need to order the materials from subcontractors. Some 300-400 enterprises are involved. Nobody makes reserve engines, there are no materials, or money for this. And apart from the engine there must also be the special control system that gives the commands. Perhaps there are some screws left over, but I doubt it," he continued, commenting on whether Ukrainian specialists would have been able to assemble an engine out of spare parts.

Therefore, the only way for Ukraine to send an RD-250 engine to North Korea would be to take it off their Tsyklon rockets in storage, which would be a move with the participation of the Ukrainian government. This is a scenario incompatible with Elleman's assumption of disenchanted ballistic rockets specialists stealing an engine to sell at the hypothetical black market. But the engine requires rocket fuel which Ukraine doesn't have.

Was an RD-250 in the North Korean rockets in the first place?

Joshua Pollack, editor of The Nonproliferation Review and a senior research associate at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, California, told RFE/RL that he disagreed with Elleman's assessment that the Hwasong-12 and Hwasong-14 rockets launched this summer contained a RD-250 engine. According to him, "they use a different, smaller main engine, and also have four small steering engines around it."

The Yuzhnoye construction bureau and Yuzhmash produced a statement saying the engine seen on the photographs from launches of the North Korean rockets was "absolutely not" an RD-250.

Even Elleman in his report acknowledged that the North Korean engine differed from an RD-250: it had one chamber.

Vasyl Chabanov told EP that the engine seen on the photographs was most likely an RD-253:

"The RD-250 was composed of two combustion chambers and one turbopump for these chambers. These constructions can only work in pairs, triplets, quadruplets. An engine with one chamber carried the index RD-253 and was produced at an Energomash factory in Perm, Russia."

Yuriy Mitikov, Head of the Department of Engine Building of the Physical-Technological faculty of the Dnipro National University, told EP that the only way that the engines on the North Korean photos are similar to the RD-250 is the diameter of the exit nozzle. But there are many engines with such a size, he told. All the diameters are similar, as they are all based on the de Laval nozzle patented in 1889, which has been gradually improved over time. Moreover, the assumption of a one-chambered RD-250 engine powering North Korea’s Hwasong-14 rocket launch is problematic, as it is inconsistent with the available photographs.

“Above is the image of Norbert Brügge based on which Elleman concluded that the engine of the Hwasong-12, and the Hwasong-14, is a RD-250. Experts estimate the Hwasong-12 could have a range of up to 4,500 km. But this is impossible with an RD-250 engine. One RD-250 nozzle generates 42 tons of thrust, meaning it can carry 28 tons of start weight. A Hwasong-12 with the weight 28 tons would be able to carry fuel to fly at most only 1-1.5 km, and that’s if it’s not carrying any ammunition,” Mitikov told EP.

Furthermore, the photo from the launch of Hwasong-14 is likely a photo-op, Mitikov said:

“Korean photos show the Hwasong-14 is a mobile complex with a wheeled hauler. The R36 where RD-250 engines were used is a silo-based missile which uses the N2O4/UDMH propellant. A mobile complex without a launch container, as we see on the photo, requires another propellant. N2O4 freezes at temperatures below zero, and boils at temperatures above 21℃, meaning that cardinal changes to the RD-250 engine to work with another type of propellant should have been made. Let’s recall that Ukraine doesn’t produce N2O4/UDMH, it buys them at the world market for working with the liquid propellant RD-861K (the third stage of the carrier rocket Tsyklon-4 or the second stage of the carrier rocket Tsyklon-4M, and the RD-843 for the fourth stage of the EU carrier rocket Vega-4. The thrust for one RD-250 nozzle is 42 tons. That means the starting weight of the Korean rocket is less than 30 tons. But its range is estimated at 6-10,000 km! In this case it is two-staged and has (if it has) a ultra-modern light nuclear warhead. The successful division of stages in flight, modern warhead - these are the most modern technologies. They demand multi-billion dollar investments into this project.”

And the presence of the North Korean supreme leader so close to the rocket is suspicious, Mitikov continues:

“The fact that the ‘bright sun of Korea’ Kim Jong-un is shown to be present at the launch of the rocket, and is standing so close to it at the photo above, makes it extremely likely that the rocket is just a dummy. The brown clouds of smoke at the launch in the photo below indicate that the rocket uses toxic hydrocarbon fuel. When a rocket is brought to battle readiness, leaks are possible, so people near it all wear protective chemical clothing. And Kim Jong-un must have a triple set of chemical clothing. Who would risk the life of the ‘supreme leader’?”

Because of the danger that a launch poses to personnel, the launch process was automated in the USSR, Mitikov told:

“The launch of the first intercontinental ballistic rocket on 7 November 1960, the anniversary of the October Revolution, was attended by Marshal Mitrofan Nedelin, he sat there in his Marshal's uniform. An accident happened, and 92 people burned to death there, including him. From that time on, big bosses at rocket launches was considered a bad omen, and measures were taken to automatize the start. The Zenit rocket launches without a single person altogether. Only the Russian Soyuz-2 rocket has a launch that needs the presence of personnel. In 1980, 42 people died at the launch.”

All this makes it extremely probable that the Koreans are making photo-ops with Kim Jong-un next to one rocket, and launching another one, which they don’t show, Mitikov explained:

“Probably, they are launching some ‘present of friends’ to escalate the situation. Showing the missile which actually can fly intercontinental distances is risky for Korea. Observers will find out, from which city it came from, which regiment, which colonel accepted it, which marks the chassis had. The many successful launches in a row speak to the well-functioning technology of the North Koreans and skillful preparation to ICBM launches. The ‘black hole’ between heads which, as the NYT publication claims, points to an RD-150 is a fig leaf obscuring the real state of affairs. Conclusion: all of NYT’s fabrications about Ukraine’s involvement in North Korea’s ICBM program stand no criticism.”

So, Elleman's statement that the North Korean rockets contained an RD-250 is disputed by both Ukrainian and international specialists.

Could Ukraine have redesigned the RD-250 to make it into a single chamber rocket?

Elleman supposed that the RD-250 was redesigned into a single-chamber engine, and that this required competent specialists: "The technical skills needed to modify the existing RD-250 turbopump, or fashioning a new one capable of feeding propellant to a single chamber would reside with experts with a rich history of working with the RD-250," he wrote.

However, the RD-253 was never produced in Ukraine, Chabanov said. And creating a one-chamber engine out of the RD-250 is a big feat.

"It’s basically a new development involving many dozens of subcontractors, with a huge amount of tests. You can see what a finished rocket engine looks like on the example of the Moon landing-takeoff engine developed in Dnipro. It’s not just a black hole. All the piping, regulators, pumps should be redesigned, apart from the nozzle, and that means die-casting. And I showed you just a 4-ton engine. Moreover, remaking the design documentation made by another construction bureau is not in the plant’s profile at all,” Yuriy Mitikov told EP.

This process could not have happened secretly, Andrew Titarenko, former Acting Head of the SSAU, told EP:

“The assertion about the use of RD-250 by North Korea is highly speculative. The modifications which are required to convert a two-chamber RD-250 into a one-chamber engine which was seen on the pictures requires considerable engineering effort, ground firing tests, and other steps, which cannot be exercised without knowledge of the enterprise management and government's knowledge. Ukraine’s long standing policy is to abstain from cooperation with rogue nations in missile area because it will undermine Ukraine's ability to operate at legitimate space industry markets. If this happens, losses will be much more significant than profits made. If information about cooperation with North Korea would become known for the government, the program would be terminated before it starts.”

The RD-250 was designed in Energomash and the Yuzhnoye construction bureau never developed similar engines by itself. Energomash handed over the design of the RD-250 for serial production to Yuzhmash. During the serial production of the engine, any deviation of the constructor documentation could have happened only in agreement with the developer, Yuzhnoye stressed in its statement.

What about Elleman's claim about "Western experts who visited KB Yuzhnoye" seeing a one-chamber model of the RD-250 on display at a local university, and a local engineer boasting about producing it, which is his main argument for Ukraine being a supplier of a modification of the RD-250 to North Korea?

Yuriy Mitikov, Head of the Department of Engine Building of the Physical-Technological faculty of the Dnipro National University, told EP that it is difficult to identify what Elleman is talking about. A one-chamber RD-250 rocket is a totally new design which had never been developed or produced at Yuzhmash. Mytikov's laboratory contains 50 engines on display as visual materials for students, with models produced both by Yuzhmash and by other enterprises. On display is also one chamber from the RD-250 from a Tsyklon rocket, cut in half to show its insides, as is a one-chambered engine which was developed at Yuzhmash but not taken for armament by the army, decommissioned, and given to the laboratory. This huge engine was too big to fit through the door of the laboratory, so it was cut in half and welded back together inside. "Maybe they saw this one," Mitikov supposed.

As for Elleman claiming there was a local engineer boasting about producing "it," whatever "it" is, this is unclear. Had the engineer worked on the RD-250, one of the chambers of which was on display? Had the engineer worked on the decommissioned huge engine which was never put into production? Had the engineer worked at another factory in Russia producing yet another of the engines on display in the laboratory? Elleman does not reveal the identities of the said experts allegedly meeting the engineer, so we may never find out.

Therefore, the scenario of Yuzhmash, with its depleted employee and material base, in recent years creating a new one-chambered design of the RD-250, secretly from Energomash, the Ukrainian government, and the whole world, at a time when this class of engines is outdated altogether, can be considered unrealistic.

So, could the engine in the North Korean rocket really be a smuggled RD-250 from Ukraine, as Elleman alleges?

Where did the engines for the North Korean rocket come from, then?

Ukrainian experts support Elleman's assumption that North Korea got external help in the development of its ballistic rockets.

A statement on Yuzhnoye's website said that the Yuzhnoye construction bureau, as well as Yuzhmash are seriously concerned with the pace with which North Korea is developing its intercontinental ballistic rocket potential, and, "as recognized experts in rocket building," consider that "this rapid development of rocket technology was impossible to achieve without external support."

As well they are "seriously concerned" that one of the most respected outlets in the world, The New York Times, is basing its analytical materials on the conclusions of dubious experts, and consider that the analysis of the situation must be done by professionals.

Vasyl Chabanov told EP that the North Korean rocket looks similar to 20-year old Russian technology and that he thinks that ready armament was purchased.

"I can't imagine another country, other than Russia," he told. "Even China has more advanced technology."

Yuriy Mitikov, however, thinks that China could be an option.

"USSR taught China how to make some rockets. Representatives of Yuzhnoye worked there, Ilarionov, our famous specialist Shmyakin taught the Chinese. Chinese students studied rocket building in Ukraine. I think that the Chinese taught the Koreans, as they are their brothers," he told EP.

Kolchuga scandal-2 or mere slander?

The publication of the NYT article and Elleman's piece appear to be similar to an information operation like the Kolchuga scandal, Mykhailo Samus told EP. In 2002, the US accused Ukraine of providing Kolchuga passive sensors to Iraq. Subsequently, no Kolchugas were actually found in Iraq, but the scandal had grave consequences for US-Ukrainian relations, Ukraine-NATO relations, and influenced Ukrainian history up till this day.

"Then, the USA was in a stage of preparation to an active phase of operations against Iraq. Now, the USA is possibly preparing against such an operation against North Korea. This is a key element for the USA. Imagine such a statement then, when the USA was preparing for operations against Iraq, that Iraq could have systems which can detect USA stealth aircraft. This was a huge blow to the preparation of the operation by the USA.

If we assume that Ukraine did supply the engines to the rockets, now they can reach the USA, and the cost of the operation changes. The USA now has to build an missile defense system, and its cost is huge, it's an absolutely other operation.

This injection of information can have huge consequences. Now the USA will be forced to stop providing weapons to Ukraine until the end of the investigation. And the investigation can be long. How can we get proof that this engine was supplied from Ukraine of Russia? We need to have the engine itself, or get some agents from North Korea, which will prove where the technology came from. This is an important element," Samus said.

"There are many similarities to the present situation. The time of publication was carefully calculated: as soon as the USA started seriously considering providing weapons to Ukraine, this injection of information took place. And the allegation that it could have been Ukrainian engines is based more on manipulations and emotions, than facts," he added.

The Center for Army, Conversion, and Disarmament studies where he is deputy director has published a statement noting that neither the NYT article nor Elleman's report contain any fact, evidence, or references to witnesses or participants of the supposed “deal” between Ukraine and North Korea - "only assumptions, conjectures, fibs and manipulative assessments."

The authors of the report reject the option of the more likely transfer from Russia or China, and allege it was Ukraine, at the same acknowledging that how the engines supposedly got to North Korea is "still a mystery."

The NYT article is based on manipulative statements and images, Samus says.

"Local engineers who are literally are ready to sell for food technologies, secrets, and often entire rocket engines to any thief, including North Korea, which is under the direct UN embargo - this is the picture that the article paints," Samus told EP. "This is like from the handbook of Russian propaganda, a manipulation aimed at those who don't know what's happening in Ukraine."

He added that in order for one to violate the UN embargo at a time of war when a European country such as Ukraine must maintain its image to maintain international support, a serious motivation must be present, and a deteriorating financial situation is not an adequate motivation for that.

What puzzles Samus is that Michael Elleman should be well informed about the situation with RD-250 rocket engines in the post-Soviet space, having worked on dismantling long-range rockets in Russia, and especially about the fact that, unlike Ukraine, Russia many engines and their individual elements, and that they can be easily transported to North Korea from Russian territory. Samus suggests that Elleman has either fallen prey to the Russian special services, is part of a Russian information operation, or both.

Acting Head of the SSAU Yuriy Radchenko, however, thinks that this publication was inspired by Russia to discredit Ukraine and lower Ukraine's rating on the market of space goods. The USA is Ukraine's strategic partner in space technologies, and Ukraine participates in the project with ANTARES and Sea Start. As well, Ukraine's goal is participation in the European Space Agency. A scandal casting a shadow on Ukraine's main space producer would seriously undermine international collaboration.

And Head of the National Security and Defense Council Oleksandr Turchynov has said that the publication was “most likely triggered by the Russian special services to cover their own crimes."

However, so far, the US State Department has remained unconvinced by Elleman's report.

"In the past, I know that Ukraine has prevented the shipments of some sensitive materials to nations that we would be certainly very concerned about," Heather Nauert, State Department spokesperson told at a briefing. According to the official, Ukraine and the United States have a good and solid relationship. "We don't comment on intelligence reports. Ukraine, though, we have to say has a very strong nonproliferation record and that includes specifically with respect to North Korea," she said.

Should Ukraine sue The New York Times?

Yuriy Radchenko thinks not, as the USA is Ukraine's strategic partner.

"It's not in our interests to spoil our relations with the USA, and all the more because of the position of a journalist.[...] The USA is the main customer of Ukrainian space equipment. The reaction of the factory is enough. Ukraine's reputation will not suffer," he said at the press briefing.

But Volodymyr Horbulin, who recently published the book "The global hybrid war. The Ukrainian front" thinks Ukraine should take a more active position.

"We are constantly under unfair attacks and accusations. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs should suggest conducting an investigation into where North Korea got its nuclear weapons. Does it have Chinese, Russian roots? These countries support relations with North Korea. Are relations between North Korea and Iran, which is accelerating its missile program, possible? We should conduct this investigation so that these attacks on our country as a country that is constantly selling something prohibited by international conventions would stop. [...] In 1997 I signed the Missile Technology Control Regime in the name of Ukraine. I don't know of a single episode of trade of artillery and ground-to-air missile systems with Iran, and no fact was proven, but despite this Ukraine was constantly in the headlines, being accused of such trade. We areana honest, decent country, and, what is most important, we are the only country in the world which voluntarily gave up its third largest nuclear potential," Horbulin told, saying that Ukraine should actively defend itself from unfair allegations.

Read more:

- Problems with the NYT article on Ukrainian rocket engines in North Korea

- Dnipro will not let Ukraine's space glory be forgotten

- Top-10 space achievements of independent Ukraine

- Canada's first spaceport will launch Ukrainian rockets

- Ukrainian MarsHopper won NASA Space Apps Challenge

- Ukraine to regain position in world space and missile industry

This article has been changed from its original version, which said Marsal Nedelin sat at the rocket launch in chemical protective clothing. In fact, he was wearing his Marshal's uniform.