As of 20 April 2017, 42 children have died and 109 were injured in result of mine explosions in Donbas.

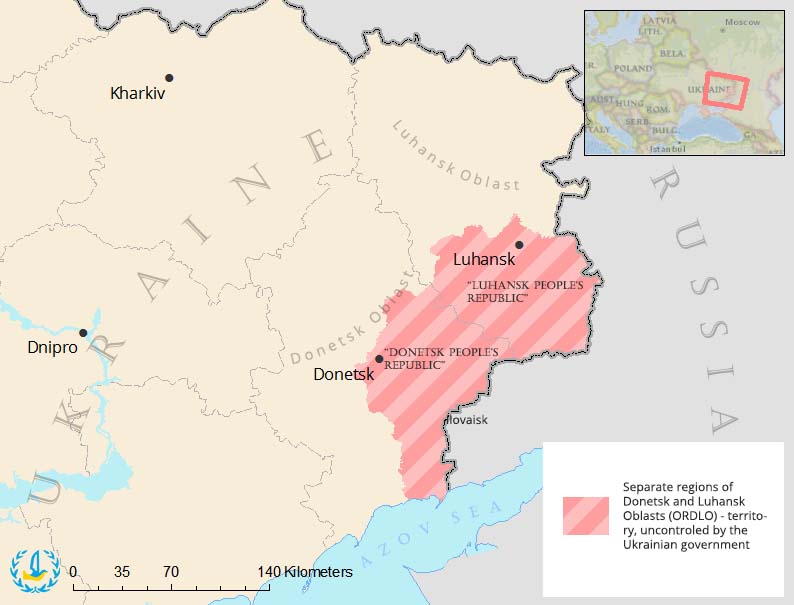

Specialists say that some 7,000 square kilometers ha of the area in Donbas need clearing from mines, which will take from 10 to 15 years. According to Serhiy Zubarevskyi, who heads the anti-mine activities of the Anti-Terririst Operation staff, settlements on the contact line between territory controlled by Ukraine and the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics, uncontrolled by Ukraine, are the most vulnerable to mine detonations.

Mines can be found literally everywhere, as the risk zone can be virtually any spot on both sides of the contact line.

In 2006, the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining Stockholm International Peace Research Institute found

that Ukraine ranks first in the amount of anti-vehicle mine incidents in 2016, accounting for 26% of global casualties.

Schoolchildren are especially vulnerable to mines, as this age makes them curious to everything surrounding them. They are being taught to avoid them in lessons in school and kindergarten, as well as in videos and cartoons. At a press conference held at the Ukrainian Crisis Media Center, participants of the programs of the Swiss Foundation for Mine Action, told about their experience in Donbas:

“The children who live in the conflict area are pretty familiar with all this explosive stuff. When you ask children in kindergarten as to what dangerous things you can find in a forest, they name ‘booby-traps, bombs, grenades’ and only then toadstools and wolfs. This film was made to tell about these children,” said Olena Rozvadovska, a volunteer, participant of the programs of the Swiss Foundation for Mine Action.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dd7DYRIsa-M

The leading character of the film is Oleksiy, a boy from a village near Pisky. He found a detonator of a grenade and lost three fingers playing with it. “It’s scary when war goes over the souls of children. The consequences are terrible. We made this film to remind society that these children have to be saved. People build a resistance against news from the frontline, they cease to see the people behind the numbers," said the director of the film Taras Tomenko.

This video is part of the stopmina.com project, which gathers materials for teachers to tell kids about mines.

“During the lessons, we followed the strictest security norms. We did not touch the objects not to give children impression that they can be touched,” said Rozvadovska. “Teaching explosives' security is one of the fundamentals of mine action. It is important to convey these simple instructions ‘stop, step back, tell the adults’ even to the youngest of them,” says Michael Barry, program manager of Swiss Foundation for Mine Action in Ukraine.

On 15 May 2017, the Foundation launched a program to demine the city of Sloviansk, which had been liberated from Russian-hybrid troops in 2014.

Perhaps the most widely publicized story of a child from Donbas who suffered from a mine is that of 11-year old Mykola, who was left as a triple-amputee after the detonation of a live grenade he and his brother found in his backyard. His brother was killed in the explosion.

He underwent surgery and reabilitation in the hospital of Canada's Montreal, after which he returned to Ukraine.