On the day that my mother sold the pet deer to the Nazis, school had ended late and she ran through a light breeze blowing off the mountains. Angry and embarrassed, she hoped to get home before the family, out harvesting since dawn. At age ten, she was too young for field work but still had to peel potatoes for dinner, even in the middle of a world war. Maybe they would have potato pancakes, crispy the way she liked them, with scallions and buttermilk.

She slowed to a skip in sight of their traditional longhouse, painted in the style of the day, with red logs and white mortar. Bathed in the golden autumn sun, the apple trees in the orchard bowed low with fruit. She barely needed to reach to pick one for a snack, though she could climb like a monkey for summer cherries.

When a group of German soldiers walked past, she paid them little mind. In 1943, they were a regular sight around Kulaszne, an ethnic Ukrainian village nestled on the Carpathian Mountains in southeastern Poland. Hitler’s occupying armies used its paved road and train station for transit from the Eastern Front.

What was not a regular sight for the Germans was the docile deer sniffing the apple in my mother’s hand.

While mushrooming in the forest, my grandparents, Petro and Anastasia Dembicki, discovered the orphaned fawn in the spring of 1940 – less than a year after Hitler and Stalin partitioned Poland and Kulaszne ended up on the German side of the border.The pampered fawn drank cow’s milk and slept in bed with the girls, her gangly legs tucked neatly under her belly.

A European roe deer, like Felix Salten’s original Bambi — until Disney made the fictional character a much bigger American white-tailed deer — the tiny fawn delighted my mother Kasia, then seven; and her two older sisters, Parania and Hania.

They called her Serna — the word for “deer” – and the pampered fawn drank cow’s milk and slept in bed with the girls, her gangly legs tucked neatly under her belly.

By June 1941, when the mountains roared with the Nazis marching east to invade the Soviet Union, the doe had grown too big for the bed and slept on pillows in a special pantry inside the Dembicki house like a panyanka, a fancy miss, and not in the stables with the livestock.

The house stood in one tiny corner of the vast killing fields between Berlin and Moscow, where Hitler and Stalin, using mass violence on a scale never before seen in human history, murdered 14 million civilians in just over a decade. That number included the Holodomor: Stalin’s deliberate starvation of 3-5 million Ukrainians in 1933; and Hitler’s murder of 6 million Jews in the Holocaust. It did not include the 12 million World War II dead.

This is a story of the Bloodlands.

It is also the story of a pet deer, that didn’t know and couldn’t care.

Lavished with family leftovers, Serna grew larger than a wild roe deer. They rarely tied her, so she leaped in and out the patchwork of neighboring garden plots that embroidered Kulaszne’s fields. The tame woodland creature charmed the villagers. On Sundays, when the Dembicki family promenaded to the village’s Greek Catholic church, dressed in the finery that Anastasia made on her prized Singer sewing machine, Serna always followed. Sometimes, the doe even clambered up the wooden stairs into the nave and one of the sisters had to keep her outside until mass had ended.

Perched on a river-laced highland with majestic views of the surrounding Carpathians, Kulaszne was part of an ethnic region called Lemkivshchyna. A millennium ago, most of the mountaineers adopted Eastern Christianity and paid tribute to the princes of Kiev. But they spent the modern era as a part of Poland and the Hapsburg province of Galicia. Though isolated and poor, Lemkivshchyna produced a rich folk culture including unique wooden churches — built without a single nail – later recognized by UNESCO. Depending on the century, the people called themselves Rusyns, Ruthenians, Lemkos, Galicians, Ukrainians and Greek Catholics. But mostly they called themselves Nashi, “our people,” and all that meant for certain was: they were not Polish.

It also meant trouble. After World War I, when a resurrected, nationalist Poland won Galicia – including Lemkivshchyna — it forced assimilation on the large Ukrainian minority. Then World War II put a temporary end to Poland altogether and Lemkivshchyna came under German occupation.

Soon afterward, Kulaszne’s grade school, made Polish during the 1930s, reopened with a Ukrainian teacher. As the occupation wore on, Kasia enjoyed her studies, especially poetry and history. But she was also a tomboy, who loved to climb trees and run through fields, jumping puddles, with Serna, the size of a goat kid, scampering alongside. They were so inseparable, the other schoolchildren nicknamed Kasia “Serna” too, especially the boy who stuttered. He had just taunted her again that day in September 1943, making her run home to escape.Charmed by the tame deer, one of the soldiers smiled and spoke in German, pointing first to Serna and then to himself. “Albert.”

“Se-se-se-se-serna. Se-se-se-serna.” My mother repeats the stinging, stammering words seven decades later. She considered it bullying. I suspect the boy had a crush on her. Either way, being called a deer rankled. So, when the German soldiers found her and Serna in the apple orchard, Kasia was feeling peeved.

Charmed by the tame deer, one of the soldiers smiled and spoke in German, pointing first to Serna and then to himself. “Albert.” He waved his hand to the north and spoke many words but Kasia only understood one: “Berlin.” Albert wanted to take Serna to Germany. She shook her head. The deer was her pet.

Was she foolish or brave? The occupation of Poland had grown increasingly brutal by 1943. But Kasia was too young to imagine what these hardened fighters, returning from the meat grinder of the Soviet front, had seen – and done.

Or perhaps Albert had seen enough and Kulaszne’s stunning mountain vistas touched something good. Because instead of just confiscating the little girl’s deer – or worse – he offered Kasia ten German marks, holding out the unfamiliar paper currency for her to see.

“What did I know of German marks,” she asks today, after nearly sixty years in the US “Kids now understand money from the cradle.” But she knew the paper had value. She also wanted the other children to stop calling her a deer. If she got rid of Serna, maybe they would stop.

So, she sold the pet deer to the Nazis.

“Stop calling them Nazis,” my mother complains when I put it that way. “The German soldiers weren’t all monsters.” Most likely Albert was a conscript, like the other cannon fodder that Hitler and Stalin sacrificed to the Bloodlands for their imperial schemes.The soldiers leashed Serna with a leather cord to lead her away from the orchard towards the train station at the southern end of the village.

The soldiers leashed Serna with a leather cord to lead her away from the orchard towards the train station at the southern end of the village. Unused to being tied, the doe barked and tugged, flashing out her white rump patch in protest until Albert distracted her with a biscuit.

When the family returned from their field work to find Serna missing, recriminations rattled the house. Grabbing the money in one hand and Kasia in the other, sixteen-year-old Parania marched her sister down the road, berating her the entire way. When they reached the train station, crowds of soldiers prepared to board the open troop wagons. Cigarette smoke and coal fumes permeated the air.

The girls saw no sign of their deer or Albert. But when Parania pleaded with the other soldiers in broken German, Serna heard her voice and began leaping and banging inside one of the wagons. Her ties broke and she bounded out of the train to join her humans, happily wagging her nubbin tail under their petting hands.

What did those battle weary soldiers see in the mountain girls with their beloved pet deer in the middle of history’s most murderous war? Whatever it was, when Parania held out the ten German marks to buy Serna back, they agreed.

The doe returned to the Dembicki home, indifferent to the tragedies unfolding around her as the war shifted and the front began pushing west. When the fighting reached Kulaszne in the summer of 1944 and explosions rattled the mountains for weeks, the family took Serna with them to hide in the cellar. But the doe quickly inured to the sounds and preferred the outdoors. Then the Soviet Army came, slovenly and coarse, looting and thieving, stealing Petro’s boots and Anastasia’s Singer sewing machine. But the tame deer evaded their notice or interest.

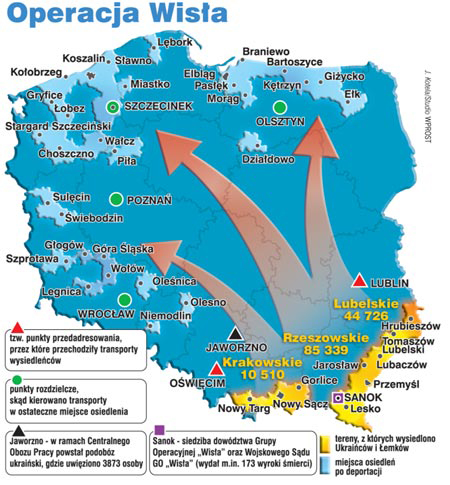

When the war ended, Moscow demanded the ethnic cleansing of millions to match Eastern Europe’s new borders. Communist Poland expelled 7 million Germans to East Germany, and they were replaced with 1.5 million Poles expelled from the USS.R. The nearly 700,000 Ukrainians who remained in Poland – including Lemkivshchyna– were supposed to voluntarily resettle to Soviet Ukraine.

After the front passed in 1944, Soviet agitators blanketed the mountains with leaflets and public meetings, urging resettlement to the Communist paradise. Serna, by then full grown, sometimes followed the family when they went to listen. But the deer ignored the propaganda, as did most of the people. Few wanted to exchange their mountain homeland for the dry, dismal steppes of the Soviet resettlement districts.

By 1945, Poland began resorting to force, burning villages and shooting civilians to terrorize the population into leaving. But unlike the Germans expelled from Poland and the Poles expelled from the Soviet Union, the Ukrainians of Poland may not have had a state to call their own (even if controlled by Moscow). But they had an army.

The Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) fought for an independent state, primarily against Soviet forces and Poles but also against the Nazis in one of the most significant resistance movements to an established Communist regime before the Soviet war in Afghanistan.

UPA, and especially its political arm, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, provoke controversy to this day for bigotry and brutality. But the tragic choice between Hitler and Stalin presented only shades of grey. Few who bore arms in the Bloodlands had the luxury of clean hands.

In the summer of 1945, as Soviet forces pushed UPA deeper into the Carpathian forests, some units began crossing the mountains into Lemkivshchyna. Young men, including my late father, Myron Mycio, rushed to join them and defend their villages against Polish attacks. Sometimes, at night, UPA insurgents would come to the Dembicki’s house for food, and the girls would be very quiet, both excited and afraid to hear their cryptic whispers.

On a gloomy afternoon that August, a neighbor spotted Serna eating in his cabbage patch. Well fed, the doe was usually easy to chase off. He threw a stick at her – gently, he later said — but fatally, when it struck her head.

Serna died instantly. The neighbor wept as he carried her body down Kulaszne’s rainy road to the Dembicki’s home. The family met the news with lamentations and many tears – followed quickly by praise for the delicious venison the pampered pet provided for her own funeral feast. Meat was a luxury, especially in such dangerous times.

Soon afterward, the Dembicki house was torched and burned. Polish attacks grew more frequent and brutal — in part, perhaps, because many soldiers were Poles expelled with the same kind of violence from Soviet Ukraine.

In the Bloodlands, brutality begat brutality.

Reports and rumors of extrajudicial mass murders spread swiftly. When Kulaszne’s church bells rang out in the summer of 1946 to warn of the Polish army’s approach, Kasia raced with her mother across the fields under a barrage of bullets, one screaming so close to her ear she still can’t believe it didn’t kill her. They sheltered in the forests, UPA’s terrain, where the Polish army didn’t dare go.

Though UPA sometimes retaliated by targeting Polish villages involved in attacking Ukrainian civilians, they mostly sabotaged Polish army units to stave off the resettlement, at least for time.

Starting on 28 April 1947, the 150,000 Ukrainians still remaining in southeastern Poland — including the Dembicki family — were given two hours to pack only what they could carry before Polish army units forced from their homes. Confined in open air assembly points and surrounded by barbed wire until they agreed to “voluntary” resettlement, they were packed into cattle cars for one-way journeys to the empty, ruined lands once populated by Germans. Deliberately dispersed, under constant surveillance and fearful of identifying as Ukrainians or even speaking of the deportation, they raised their children as Poles.

Operation Vistula was a coda to the Bloodlands, the last ethnic cleansing in Europe until Yugoslavia collapsed in the 1990s. Instead of the mass extrajudicial violence and killings of 1945-46, the Polish army “merely” arrested and imprisoned those who resisted or sympathized with the Ukrainians. But Operation Vistula murdered a culture. Homes, community centers, even entire villages were razed and many of the beautiful wooden churches, burned. In many cases, the sole surviving records of the churches are watercolors made by the artist Antin Varyvoda:

That summer, UPA began fleeing to the West. My father made it to Vienna before the Red Army captured and sentenced him to nine years in the Soviet Gulag’s harshest prison camps. In one of those black ironies of the Bloodlands, this was good for me, since I wouldn’t otherwise have been born. Freed in 1956, he returned to Poland, found Kasia working as an economist and married her within months. Less than four years later, with my brother and me, they immigrated to America.

The story of Serna is one of my earliest memories. To this day, I love deer, even if they decapitate the backyard tomatoes. The tale also tied me to a distant land impenetrably hidden behind the Iron Curtain. When restrictions eased in the 1980s, I backpacked through the wild, abandoned mountains of Lemkivshchyna with university students — the children of Operation Vistula survivors — who were only then learning of their Ukrainian roots.

Fully assimilated, unlike their parents, many would later be the bridges that brought together Polish and Ukrainian activists and intellectuals in the early 1990s, easing post-Soviet reconciliation in what could have been more explosive than former Yugoslavia. Perhaps Operation Vistula was a price for the geopolitical rapprochement between Poland and Ukraine — all the more important today – despite occasional extremists on both sides. I was born in former Prussia because of Operation Vistula. But I personally bear no grudges for the past. The future interests me more.

A minority has returned to Lemkivshchyna. Kulaszne is now home to two hundred people and even has a new church my family helped build. But it is a fraction of the pre-war population and the scores of ghostly non-villages surrounding it – including my father’s – will never return. After seventy years, the strip of depopulated lands along Poland’s southeastern border has long since gone feral. Abundant elk, roe deer, and wild boar have brought lynx and wolves to hunt them in the encroaching forests.

Only the handful of surviving wooden churches, orchards growing incongruously in the wilderness and Cyrillic tombstones in overgrown graveyards mutely testify that this had once been a homeland, where a pet deer named Serna scampered over cultivated fields, went to church on Sunday and charmed the most war-hardened of hearts.

[hr]

Related:

- The lessons of the Vistula Operation

- “Rebellious pagan” Ukrainian poet Antonych receives English translation

- Ukrainian mosaic: five unique ethnic groups

- Watercolors of wooden churches destroyed in Operation Vistula to be published as book