There are some old photographs which seem to preserve the subject in the amber light of a previous decade. Bohdan Ihor Antonych stares back at us from the thirties, sometimes with owlish spectacles, looking preternaturally boyish.

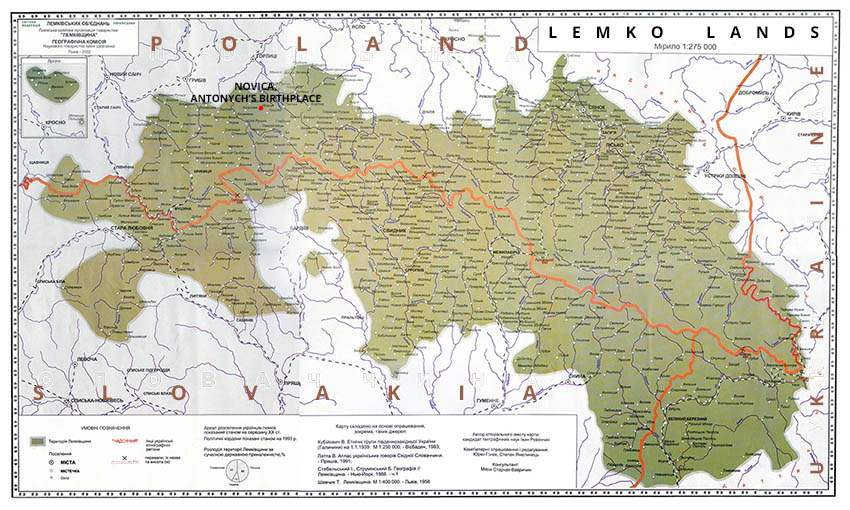

He grew up in the Lemky area of Ukraine which was then part of Poland, the son of a rural priest. The Lemky (Ukrainian: “Лемки”) were an ancient Ukrainian mountain tribe and lived a life that had remained unchanged for centuries. Their farmsteads clung to Carpathian foothills and villages shadowed by mountain peaks like mute indifferent Gods. Their Ukrainian was rich with dialect words and their lives were governed by the rhythms of the seasons. The old, pagan deities lingered among the pine forests and haunted a superficially Christianised world.

In his poetry, the boundaries between the narrator, the natural world and the music of the poems become blurred within an ecstatic pagan celebration of life. His boyish face reflects his almost perpetual sense of rapture, not only with nature but with the human world. He can exalt in the sound of jazz from behind a wall in an alleyway, a heap of rusted cars, and a cloud shadow sailing over the pasture. This seemingly effortless febrile absorption in life masks his dedication to his craft.Moss warms “like cat fur,” and the nocturnal forest becomes an orchestra playing music that manifests itself as light.

Although he would have been surrounded by people speaking the Lemky dialect in his childhood, he attended a Ukrainian language grammar school and, between 1928 and 1933, Lviv University. He wrote in literary Ukrainian, but his work was sprinkled with dialect terms and has a fevered energetic imagery reminiscent of Dylan Thomas. Moss warms “like cat fur,” and the nocturnal forest becomes an orchestra playing music that manifests itself as light. He uses many verse forms, ranging from sonnets comprising two quatrains and two tercets, to free verse, and numerous improvised stanza forms.

Antonych’s death deprived Europe of one of the greatest talents of his generation. His work, with its mystic overtones, was ignored by the Soviets. Starting from the mid-1960s, interest in his writing has revived in the Ukrainian diaspora, but he remains relatively unknown. His poetry with its elemental power is a worthy introduction to a great and neglected national literature.

Read also: Ukraine’s Executed Renaissance and a kickstarter for one of its modern successors

Antonych and Ukrainian language literature remain curiously invisible in the Anglophone world. I could pick up English University textbooks in the seventies and see Ukrainian described as a dialect and its literature as “minor.” The West was blind to the reality of intra-European colonization. The views of Ukraine’s colonizing power, Russia, were treated as if they had the scientific validity of Boyle’s law. What I might call the Russian paradigm of a primitive Ukrainian peasantry being civilised by its more advanced neighbor prevailed. This is a gross untruth, yet it means that Ukrainian is reflexively treated as inferior.

However, Ukrainian literature has distinct qualities which renders it neither better, nor worse, than Russian, but merely different. Taras Shevchenko (1814-1861) may have been the only major nineteenth-century European poet ever to have been owned by another human being. Tsar Nicholas 1 personally wrote on the order condemning him to exile that Shevchenko was “forbidden to write or to paint” (Plokhy 49). He, and many Ukrainian authors, represents better than their Russian counterparts the voice of the peasantry. In his work, the often mute or comic peasantry of Gogol (or Hohol in its original Ukrainian form) and Chekhov acquires a tender humanity. The latter authors grew up speaking Ukrainian. However, the empire’s linguistic policy, its effective banning of a language, led to them writing in Russian, infusing that language with a quirky Ukrainian lyricism. Even today there are a small and diminishing number of writers who translate their text internally into Russian. The very act of writing in Ukrainian was, therefore an act of rebellion against imperial hegemony.

Related: Let the songbird out of the cage – vote for Ukrainian literature

The Empire, of course, always strikes back and, indeed, usually delivers the first blow. The long standing animosity towards Ukrainian culture emanating from Russia was summarized in a Chatham House paper of 2012:

Taras Shevchenko’s legacy, Ukrainian language, and the Ukrainian ‘national idea’ of the last two centuries… appear to be meaningless, second-rate or blasphemous to a large number of Russians. Generations of Russian intellectuals have turned belittling of the Ukrainian language and culture into a part of the Russian belief system alongside anti-Tatar and anti-Muslim stereotypes. But whereas the latter are built around national differences, what makes Ukraine stand out in this list is a dismissive attitude to any assertion that national differences exist (Bogomolyov and Lytvynenko, 2012).

However Antonych, of course, lived and died in a western Ukraine under Polish control. During this period the Polish state actively pursued the assimilation of Ukrainians via a program of polonization. Polish language was imposed upon Ukrainians and they were required to formally identify as Poles in order to access certain occupations. Ukrainians, of course, are both perpetrators and victims within the history of their colonization by other peoples. However, the cultural repression they experienced explains why their literature was marginalized internationally. Poland and Ukraine are embarking on a difficult process of reconciliation. Russia remains opposed to the very existence of Ukraine and still focuses on damaging the country’s image internationally.

I have noted that the very act of writing in Ukrainian was political. Antonych entered an ecstatic state to write his poetry. He is able to convey transcendence through his absolute commitment to his craft. He is also the representative of a pagan culture that survived, relatively unchanged, from the dark ages. He combines the visionary qualities of Blake or Clare with Shelley’s craftsmanship and Dylan Thomas’s manic inventiveness.

Yet his poetry has been cited twice, in 2013 and 2015 in the Finnegan’s List produced by the European Society of Authors. The list, which is drafted by prominent European authors, consists of work that is not sufficiently represented in translation.

Antonych has never been translated by a poet whose primary concern was to create a book of poetry in English and build him a reputation among readers, rather than linguists. Night Music is aimed at the reader of poetry who will, perhaps, have an image of Ukraine shaped by Russian soft power. My aim has not been to duplicate every one of his devices in English. All of Antonych’s poems are finely wrought; he loads “every seam with ore”. Yet, if we reflect all of these devices in English, we murder the poem in the target language. As Jeremy Reed says:

Poets are too often worked dead by translation. The substitution of one language for another, the attempt to match word for word the creative potential of the original, which is animated by virtue of the imagination charging the language, is the perfect means to making a poet redundant in a foreign language (Montale 9).

If we are to render Antonych’s poetry effectively into English we must reckon with the traditions of both languages. The poems in this collection are what Ukrainians might term a perespiv, a song over a song, and attempt to render his poetry as contemporary poems in English.

I have, like Antonych himself, sought to intoxicate myself with his songs and to translate more intuitively. This book strives to capture the beauty, emotion and imagery of his poetry using the resources of the English language. The reader of a translation will always inevitably be listening to the voice of a translator. However, the translator must have listened carefully to the voice of the author and tune his language so it resonates at the same pitch. A translation of this kind is not a transcription but a duet, a poet’s interpretation of a poet.

I have structured the book so that it has the emotional logic of a collection of English poetry. The reader will perceive echoes of Dylan Thomas, W.B. Yeats, John Keats, and Percy Bysshe Shelley in these poems. Antonych’s poetry is both richly Ukrainian and yet it” has no nation but the imagination” (Walcott). His work belongs to that great literature which speaks to the one abiding collective, humanity.

Below are two of Antonych’s poems.

We return slowly to the earth, our cradle.

Green tangles of vegetation bind us, two fettered chords.

The razor sharp axe of sun hews at a trunk,

The music of moss, tenderness of the breeze, the oak a proud idol.

In the wastage of days that bear us the body, warm and obedient

Grows with itself, two siblings, two flowers of fidelity.

The moss warms us like cat fur. You transform the stars into a murmur

And blood into music and greenery. The sky glows.

At the edge of day, in the ocean of heaven, the winds of the future sleep

And our devoted constellations wait under the frost,

While earth does not instruct them to arise. We abandon things,

To be borne, to grasp the stars in pure ecstasy.

The yearning of blood hurts. Eyebrows sharp as two arrows,

While above us a wall of melody echoes

The pinions of a breeze. Our fate pinned on the planets.

You burn with growth, thirsty as the earth. Become all music.

Bohdan Ihor Antonych

Translated by Stephen Komarnyckyj

First published in Modern Poetry in Translation Issue: Series 3 No.14 – Polyphony.

The refraction of the moon repeats itself in the clouds, a song,

Cloud on cloud forming a silver wall, below which the foxes bark.

Leaves dangle from the stars in oblique ropes,

The mushrooms chime their plates of rust colour,

In the forest choir,

The leaves of the oak form

A lush foam, a surf, that booms and trumpets

The unwritten law of night.

Wolves bring their sacrifice of blood and flesh,

Wiping their muzzles on musical flax.

Night of predatory law and dark magic. In the marsh things knead

A dull red dough of mud. Owls harmonise treason.

A star wrinkles its eyebrow at the moon,

Flower sticks to flower,

In a dew thick as paste,

The oily greenery

Becomes this coarse fabric of darkness.

The angles of roots are coiled music, plaiting

The melodies that foam within.

This is the heart of the forest,

The horizon’s secret,

Where storms exhaust themselves and lightning

Is a razor whipped across a razor,

Each broken human dream.

Its wings sweep across the earth, adorning roofs

With wreathes for the marriage of fire.

Terror, a subterranean child that cries each night

In that place where beyond knowledge of feeling or ruin

The incomprehensible, ancient speech surrounds us.

The river. Spring grinds its ice.

Bohdan Ihor Antonych

Translated by Stephen Komarnyckyj

First published in Modern Poetry in Translation Issue: Series 3 No.14 – Polyphony

Night Music was published on 5 October 2016 by Kalyna Language Press.

Steve Komarnyckyj is a British Ukrainian poet and literary translator.

Bibliography

-

Bogomolyov, Alexander and Lytvynenko Oleksandr, January 2012. A Ghost in the Mirror: Russian Soft Power in Ukraine. Briefing Paper. http://www.chathamhouse.org/publications/papers/view/181667 (Accessed 19 August 2016)

-

Plokhy, Serhii. The Cossack Myth: History and Nationhood in the Age of Empires. Cambridge University Press 2012.

-

Montale, Eugenio. The Coastguard’s House. English versions by Jeremy Reed. Tarset: Bloodaxe 1990.

-

Walcott, Derek. The Schooner Flight. (Original Source: Poems 1965-1980 (Jonathan Cape, 1980)) http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/177932 (Accessed 15 April 2014)