The situations of Russia and most post-Soviet states “in a surprising way” recall the late Brezhnev period in the USSR and are increasingly likely to end the same way, with chaos and collapse not only of regimes but of state borders, with conflicts and civil wars involving “hundreds of thousands if not millions of people,” Vitaly Portnikov says.

That prospect which the aging leaders of this region understand because they lived through it before is why they cling so tightly to power and continue to tighten the screws, the commentator says, but as at the end of Soviet times, their actions are making the approaching end an even greater crisis.

Putin’s “managed democracy” as shown most recently in the United Russia [Russia’s ruling party associated with Putin – Ed.] primaries and Tajikistan’s vote to make its incumbent president ruler for life “recall Brezhnev’s Soviet Union.” Now, as then, many understood that nothing much could be changed until the ruler departed but no one was in a real position to prepare for the changes.

Portnikov points out that the way in which the various leaders came to power has “no significance” for how they rule. Putin was given power by his predecessor. Alyaksandr Lukashenka won “the first and as it turned out the last) democratic elections in Belarus.” Nursultan Nazarbayev and Islam Karimov headed the republic communist parts and simply retitled themselves. And Emomali Rakhmon “was one of the leaders of the clan which with the support of Moscow and Tashkent won the civil war in Tajikistan.”

Thus, “the striving to preserve power among former first secretaries, former collective farm heads, and lucky chekists is completely identical,” the commentator says. “And the systems of power, despite the geographic distance of Belarus from Tajikistan is not only very similar but very Soviet.”

That is because, he continues, “at their base are not elections but acclamation, that is, the conditional approval of the population of the right of the feudal lord to eternal rule.” And these regimes have in common “a fear of the street,” a place which many of them think is financed and controlled by the US State Department.

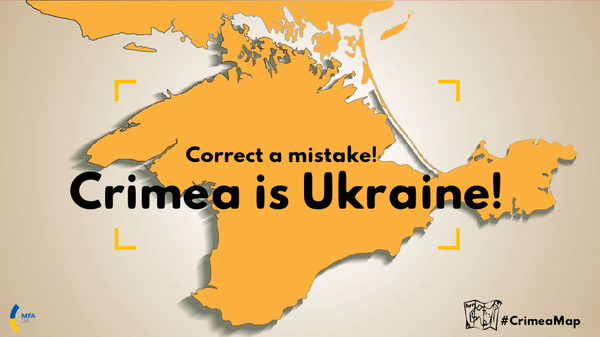

Only three of the 12 former Soviet republics – the Baltic states were occupied and very different – have been able to break out of this: Ukraine, Moldova, and “in part” Armenia. In these three the population has mobilized and changed the government and therefore they have the chance to move forward without radical discontinuities.

What these three have achieved sends fear into the hearts of the feudal rulers of the other nine, Portnikov says. It explains Putin’s approach to Ukraine and Georgia and it is behind Nazarbayev’s recent promise “not to allow a Ukraine in Kazakhstan.”

There is a particular reason for concern just now: “many of the leaders of the former Soviet republics are already far from young.” Given that their state machines “are constructed exclusively on the authority and influence” of their leaders, the departure of one or more of them will set in train radical shifts.

No one knows just what will happen, he says, because in these countries “you cannot discuss with politicians or journalists the simple question ‘what will be after’ because no one knows the answer to that.” Another problem with these states is that their administrative apparatuses are “practically completely ineffective,” hence the “hands on” approach of the rulers.

Thus, in the very near future, “the post-Soviet space [will be] on the brink of the most destructive crisis in its history after the collapse of the USSR,” on that will change “not only regimes but state borders and become the cause of clan fights and civil wars” involving “hundreds of thousands if not millions of people.”

And “the cause of this crisis is the feudal ‘stability’ established after the collapse of the USSR and which in fact represented a return to Brezhnev stagnation.” Both then and now, the system looked eternal – but when it began to fail, it failed and will fail completely, perhaps triggered by “’the untimely end’” of a ruler. With that, “chaos and collapse will follow.”

The unfortunate fact is that the nine feudal states cannot find the way forward as Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia have. There is in them no popular sense of responsibility for the future, no real opposition in the government, and thus “in the event of a collapse of the regime, the street will rule, not limited by anything.”

“The rulers understand this,” Portnikov says in conclusion; and therefore “they so fear ‘Maidans.’” But instead of taking the steps that might make collapse impossible – involving the population in real politics, “they only tighten the screws more tightly, without suspecting that doing so is one of the clear signs of the approaching end.”

Related:

- Putin regime has long had an ideology — Great Power Imperialism — Pavlova says

- Why Americans are “stupid,” according to Russians

- Incredibly shrinking — Putin’s ‘Russian world’ in the post-Soviet space

- Putin is Russophobe-in-chief in Russia’s war between the pro-Soviet and the post-Soviet

- Russia’s thirty somethings: can we rely on the first post-Soviet generation?

- Changing even administrative borders no easy thing in post-Soviet states

- Six post-Soviet countries now say they were occupied by the USSR

- Putin has destroyed any possible basis for unity on ‘post-Soviet space’

- Moscow’s neo-imperialism seen sparking more Maidans in post-Soviet states

- Ukrainians represent not a post-Soviet but a new leading cultural layer