Moscow has been abuzz in "Victory Day" fever for weeks. Toddlers, puppies and tanks are draped in the ubiquitous orange and black striped St. George Ribbon, a symbol previously associated with patriotic veterans and war heroes of World War II, known in Russia as the Great Patriotic War. The ribbon has recently morphed into a symbol of Russian patriotism and nationalism expressed in a highly militaristic show of might, culminating in the May 9th military parade and related festivities.

This transformation of the symbol has coincided with a marked transformation in the Kremlin. Since 2014 we've witnessed an aggressive war in Ukraine as well as the intense Kremlin-directed and inspired propaganda campaigns against the US and Europe. It's not a coincidence that Sputnik "news" outlet was formed in 2014 with the logo of the orange and black stripes of the St. George ribbon. The adoration of the symbol in its new incarnation is such a phenomenon that there is now a name for it in Russian – Победобесие (Pobedobesie), a linguistic portmanteau comprised of pobeda, "victory," and bes, the root of the word for "demon."

This transformation of the symbol has coincided with a marked transformation in the Kremlin. Since 2014 we've witnessed an aggressive war in Ukraine as well as the intense Kremlin-directed and inspired propaganda campaigns against the US and Europe. It's not a coincidence that Sputnik "news" outlet was formed in 2014 with the logo of the orange and black stripes of the St. George ribbon. The adoration of the symbol in its new incarnation is such a phenomenon that there is now a name for it in Russian – Победобесие (Pobedobesie), a linguistic portmanteau comprised of pobeda, "victory," and bes, the root of the word for "demon."

While Russia is raging with "Victory Day" fever, and, incidentally, sponsoring celebrations of Russia's defeat over fascism in some 70 countries this week, many inside Russia also see not a small amount of hypocrisy and exploitation. Not only is the Kremlin using the symbol of the horrific suffering and sacrifices of tens of millions of Soviet citizens to justify and even spread its own aggression into Europe, but it distorts its own history while reverting to a repressive climate against its own citizens with unmistakable signs of fascism.

Last week was the anniversary of the Bolotnaya Square protests in Moscow. On May 6, 2012, the eve of Putin's third inauguration, hundreds of thousands of Russians of all political stripes took to the streets of central Moscow to demand a fair election after learning of widespread election fraud. The Kremlin responded ruthlessly, with riot police, batons and mass detentions.

Putin is rumored to have told his inner circle later that evening: "They ruined my special day. Now I'm going to ruin their lives." These words were apparently a call to action, because the first arrests began shortly thereafter. In the days and years following the Bolotnaya protests, dozens of innocent people have been subjected to interrogations, investigations, prison and much more.

Peaceful protesters who had participated in the largest demonstrations since the fall of the Soviet Union in a Russia whose Constitution specifically guarantees freedom of speech and assembly, suddenly found themselves criminal defendants in the Bolotnaya case. They displayed remarkable dignity and courage, charged with assault and rioting when they themselves were the ones being brutally beaten by riot police. Some of the victims tried, unsuccessfully, to sue the police for brutality.

Bolotnaya was a striking example of the personal courage of so many of Russia's political activists.

The Start of the Jailing of Russia's Opposition. Bolotnaya was also a striking example of the growing totalitarian climate in Russia under Vladimir Putin. When Moscow courts started to hand down multi-year sentences to protesters, it became clear that the Bolotnaya trials were a part of a wider crackdown on Russia's opposition. A series of repressive laws together with media campaigns against leading opposition figures as "traitors" had sown fear among many. Whether people disagreed with particular government policies or they just wanted their government to abide by its own Constitution, the feeling among the opposition was that dissenters were going to be "broken" so that anyone even thinking of criticizing the Kremlin would get the message loud and clear: Putin is here to stay, and anyone who doesn't agree with him can be silenced one way or another.

Some took this ominous message as cause for even greater determination to continue the protest movement. Sergei Udaltsov, a Bolotnaya organizer who was himself facing a multiyear prison term for conspiracy to provoke mass unrest, responded to the first Bolotnaya verdict on Twitter in November 2012: "Four and a half years for Luzyanin is a challenge to society and the start of the jailing of the opposition. We can only protect ourselves by coming out into the streets en masse."

But it was in neighboring Ukraine the following November where protests grabbed the headlines and took on an ominous meaning for the Kremlin. When Ukraine's protest movement on Independence Square ["square" is "maidan

" in Ukrainian] in Kyiv became the Euromaidan Revolution of Dignity and successfully ousted a corrupt president Yanukovych, the Kremlin reacted swiftly and aggressively, unleashing a propaganda disinformation campaign to discredit the new Ukraine as a fascist Western coup. Again Putin had to show who's boss, this time to the new Ukrainian leadership in Kyiv. Thus began Russia's assault on Ukraine, annexing Crimea and staging an insurgency in the border region of Donbas. Though Crimea's seizure was touted as bloodless, Ukrainians and the indigenous Crimean Tatar populations have suffered under Russian rule, with many missing, jailed and killed. And the war in Donbas, continuing to this day, has killed over 10,000 people, injured and displaced millions more.

Seeing the Writing on the Wall. As Russian troops were carrying out their war in and on Ukraine, the Kremlin seemed to have realized that perhaps it hadn't been tough enough on the opposition. (Some Bolotnaya victims had been amnestied before the Sochi Olympics, for example.) Despite the Bolotnaya trials and convictions, Russians were still organizing protests, and perhaps they would gain momentum from Ukraine's successes. Hence, we saw the ratcheting up of propaganda against Ukraine, the Maidan protests, and Russians who supported them. Russian media so bombarded audiences with images of fires and smoke and chaos on Maidan, that the very word "Maidan" has become a kind of generic term for violent and bloody upheaval, not protest.

Ironically, it was Putin's lashing out at Ukraine that gave Russia's opposition even more inspiration for protest. As Russians were feeling the seismic effects of Putin's foreign policy – international sanctions and crumbling relations with the West – Boris Nemtsov, a prominent opposition leader and a Bolotnaya organizer, helped to rally tens of thousands of Russians after Bolotnaya in anti-war and anti-crisis protests in March, just after Russian troops seized Crimea, and in September of 2014, after a summer of intense fighting that brought Russian "volunteer" soldiers back in body bags.

And then on the eve of a third mass demonstration, dubbed Russia's Spring, Boris Nemtsov was assassinated at the foot of the Kremlin walls. The lifeless corpse of a man who seemed larger than life itself against the backdrop of the moonlit picture-postcard cupolas of Red Square was a stark symbol of the new reality of Russia in Putin's 15th year as president. The protest movement had been broken.

And then on the eve of a third mass demonstration, dubbed Russia's Spring, Boris Nemtsov was assassinated at the foot of the Kremlin walls. The lifeless corpse of a man who seemed larger than life itself against the backdrop of the moonlit picture-postcard cupolas of Red Square was a stark symbol of the new reality of Russia in Putin's 15th year as president. The protest movement had been broken.

Understandably, many opposition activists have left Russia. For those who made the decision to remain, they have nobly and courageously continued their struggle for a more open society and to free Russia from the current wave of repression and aggression. They try very hard. They protest, even if they have to stand alone as now required by law. They get arrested, even when they do obey the law. They try to participate in elections, but as Vladimir Kara-Murza eloquently points out, the process is rigged against them, in region after region. Either their signatures are deemed fraudulent, or a candidate gets disqualified for some bizarre grounds, or a leading candidate is filmed in compromising positions in a hotel room, or state TV runs a "documentary" that a leading opposition figure works for a grammatically-challenged CIA.

If you think such preposterous means to suppress dissent would be too obvious and so unsuccessful, then you don't know Putin or Russia. Russia is a security state like no other, and its leader is a former agent from a country that may have been a failed state, but it was superior in its secret services, where there were no rules and the KGB could do whatever it took to get the job done. Russia is not just a post-Soviet state. It is a post-traumatic Soviet state, as are all the former Soviet states are. But Russia still has one foot firmly in the grave of the Soviet Union, a black earth unjustly enriched by the blood of its dissenters. Instead of trying to climb out Russia's dark past, Putin has breathed new life into it. Not only are leading figures of the Soviet Union like Stalin and Dzerzhinsky back in vogue, but we see a militaristic fascism has taken hold as well.

Victory Day has become the culmination of Russia's post-Soviet fever, raging on Russian TV, RT and Sputnik. Russians are now bombarded with propaganda about rampant Russophobia in the West, conspiracies by the CIA about the internet against Russia, and about Ukrainian fascists who must be defeated like Stalin defeated the fascists in his time. And, who else is going to save Russia and Russia's glorious history from such attacks but Vladimir Putin?

Remember that it's only relatively recently that post-Soviet Russia has had access to non-Kremlin controlled information. There is a natural thirst for information, and all things Western, really, from a society that has been starved of it for generations. So Russians are particularly susceptible to propaganda, both out of deprivation and out of inexperience. Under constant information assault from Kremlin-controlled media, especially from visually powerful TV media, it's not difficult to understand why so many Russians want to believe in a simple good and evil, black and white world.

All Russians are victims of Bolotnaya and its aftermath. The laws have become even more restrictive and the space for public expression has narrowed considerably. In this light, perhaps it's not really so remarkable that four years later, people are still being arrested in the Bolotnaya matter. Anyone who was on Bolotnaya Square that day on May 6, 2012, goes into high anxiety mode at the sound of early morning noises outside their door. And their fear is well-founded because in Russia Bolotnaya is the case that keeps on giving. Anyone can get that knock on their door and find themselves a criminal defendant and a political victim overnight.

The oldest protester still behind bars is Sergei Krivov. Sergei is 55 years old and serving a 3-year-and-9-month sentence in a penal colony. He has a wife and two minor children at home.

Krivov was one of those arrested after the first wave of "May 6 Political Prisoners," as they have come to be called. He knew perfectly well that he too could become a defendant, but he didn't run or hide. Quite the opposite. He continued to do what he knew was right. He continued to protest the only way protesters can in Russia today, by standing alone in the bizarrely restricted single-person picket. Krivov held such a single-person picket in front of the Investigative Committee building in Moscow, the Russian organ responsible for launching criminal matters, demanding freedom for those Bolotnaya activists already under arrest. Protesters such as Krivov are like sitting ducks, or rather standing ducks, ripe for picking off by police. That's how Krivov found himself in the same despicable predicament as the victims about which he was protesting.

Krivov was one of those arrested after the first wave of "May 6 Political Prisoners," as they have come to be called. He knew perfectly well that he too could become a defendant, but he didn't run or hide. Quite the opposite. He continued to do what he knew was right. He continued to protest the only way protesters can in Russia today, by standing alone in the bizarrely restricted single-person picket. Krivov held such a single-person picket in front of the Investigative Committee building in Moscow, the Russian organ responsible for launching criminal matters, demanding freedom for those Bolotnaya activists already under arrest. Protesters such as Krivov are like sitting ducks, or rather standing ducks, ripe for picking off by police. That's how Krivov found himself in the same despicable predicament as the victims about which he was protesting.

So as Russia celebrates its Victory Day on May 9, a day to remember and commemorate the heroes of the past, let's remember who today's heroes are. As Russian society and its militaristic patriotism leaning toward fascism looms over its neighbors, its citizens are ever squeezed back into a virtual Iron Curtain of propaganda and repression. Russia had many heroes in World War II. Today's heroes are those who gathered on Bolotnaya Square four years ago, and those who come back again and again, risking their freedom and their lives.

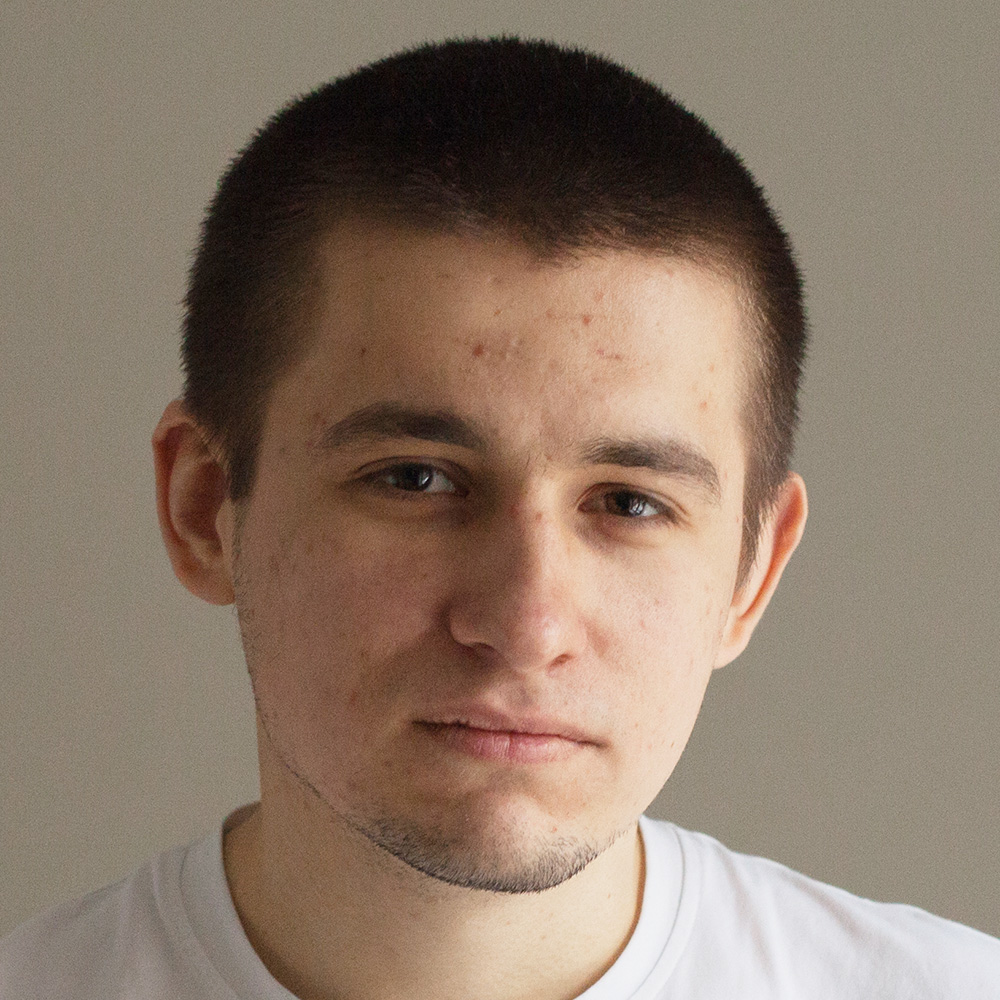

In commemoration of the 4th anniversary of the Bolotnaya protests, the Open Russia Foundation published the list of the names and faces of all 35 victims –"Freedom Prisoners" as they are called here. These are the Russian heroes whose lives have become nightmares after the events of May 6, 2012. Above all else, the site says, readers can help by sending letters so that those still locked away will know that they are not forgotten and that people still support them. Letters can be sent directly to Open Russia who will pass them on the individual prisoners. This link provides further details.

Some of the Bolotnaya defendants have been released, some have already served their time in prison, while others are just beginning their nightmare journey. Nobody knows when this will all end. That was the sentiment by one exasperated man on Bolotnaya Square this week where people gathered for the anniversary. Independent video journalist Sasha Sotnik, whose important work chronicling Russia's opposition is on YouTube channel SotnikTV, was there to capture the informal gathering and interview those who showed up to pay their respects and not let Russia's present-day heroes be forgotten. As you can see from the clip above, people were again arrested.

was the most recent to be arrested, just this April. He's charged under Criminal Code 2.212 for mass riots and 1.318 for assaulting government authority. Maksim suffers from Tourette's Syndrome. He's currently in SIZO-5 in Moscow.

was arrested on June 9, 2012 and charged under 2.212 ( "mass riots") and h. 1 tbsp. 318 ( "the use of violence against a government representative") of the Criminal Code. On February 24, was sentenced to 2 years and 7 months in a penal colony. He served his sentence in the IR-6 Ryazan region. Released on December 31, 2014.

Related:

- Moscow’s Victory cult intended to keep non-Russians within an empire and former Soviet republics together, Ukrainian commentator says

- Putin needs both: a Great Victory and a Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

- Commemoration and history: Russia’s uncomfortable truths

- Putin using Victory Day cult as Brezhnev did — to distract attention from failures and the future

- Defending our memory and pain from Russia’s Victory Day exploits

- Russia’s Victory Day: Basking in the light of another’s glory

- Social videos on victory over Nazism unite generations in Ukraine

- Russia’s CIS partners won’t celebrate Great Fatherland War Victory anymore